The Tragic History Of The 'Elephant Man'

His name was Joseph Merrick. He was talented, intelligent, and according to his friend Dr. Frederick Treves, he was "a gentle, affectionate and lovable" person. Most of all, Merrick was rare. Not merely because of his appearance but because he managed to remain gentle-hearted in the face of heartlessness. Sadly, we don't remember him as the "Kindhearted Man" but as the "Elephant Man," a constant reminder that the world didn't quite consider him human.

You would be right to point out the irony of lamenting Merrick's dehumanization while simultaneously referring to him as the "Elephant Man." Indeed, even in telling his story and delving into the dreariness of his life, there is an element of well-meaning exploitation. Heck, Frederick Treves partly advanced his standing in the medical profession through his association with Merrick, prompting some to wonder whether the good doctor was being a bad friend by exploiting Merrick. As ugly as it sounds, people far too often were unkind and downright inhumane to Joseph Merrick. And after an existence afflicted by physical misery and mistreatment, death brought a peace-less rest.

The 'Elephant Man' started off as a 'perfect baby'

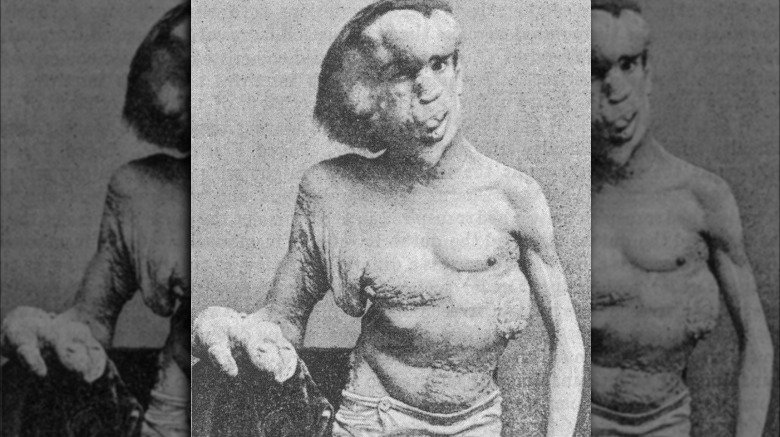

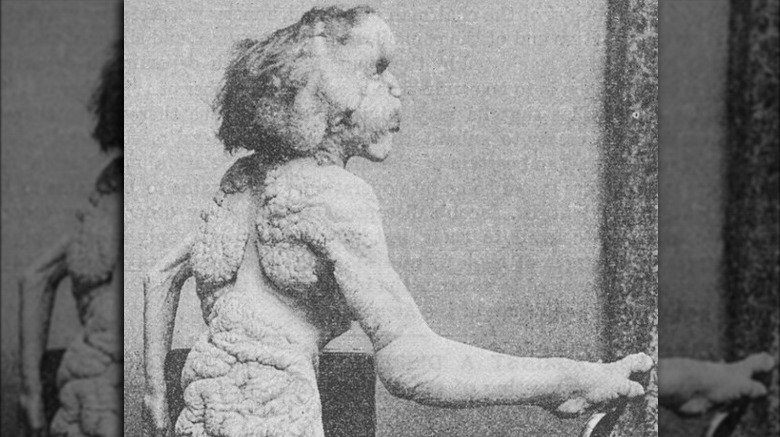

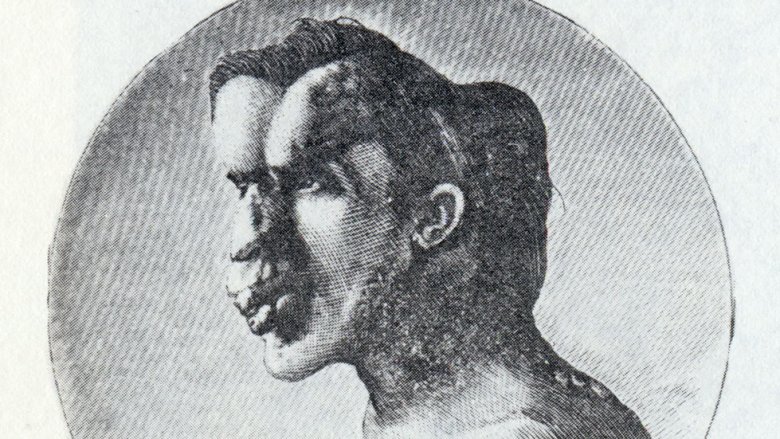

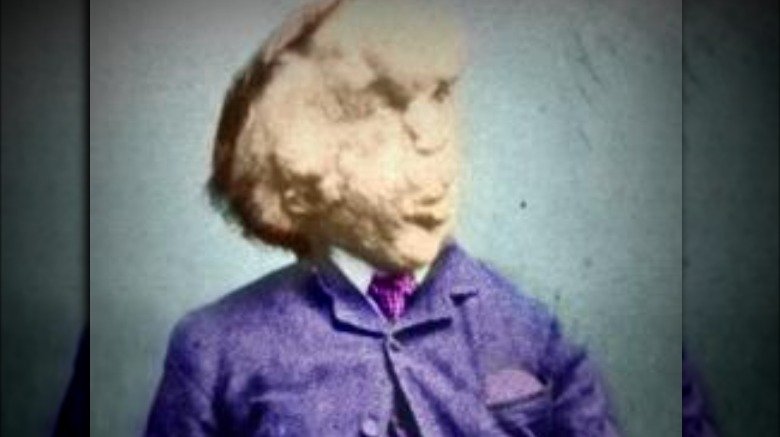

Born on August 5, 1862, in Leicester, England, Joseph Carey Merrick was the spitting image of health as a baby. As recounted in Measured by the Soul: The Life of Joseph Carey Merrick, a local newspaper article declared Merrick "a perfect baby." Shortly before he turned 2, abnormalities began to appear. The formerly flawless baby now had a bony growth forming on his forehead, a tumor protruding from his upper lip, and discolored, lumpy skin. It was only the beginning.

As the BBC detailed, the limbs on Merrick's right side became disproportionately large, far outgrowing his left arm and leg. He couldn't stand upright because his spine was "badly curved." To make matters worse, a childhood hip injury rendered him "permanently lame." Over time, he developed "warty growths, the largest of which exuded an unpleasant smell."

Measurements taken when Merrick was in his early 20s showed that one of the fingers had a 5-inch circumference. His right wrist had a 12-inch circumference. His head measured 3 feet around and was so heavy that his body couldn't accommodate it. In 1890, Joseph Merrick died when he decided to lie down. Sources differ on the exact cause, but the weight of his cranium either suffocated him or dislocated his neck. In the years between cradle and grave, he would endure indignity after indignity, cruelty after cruelty, all while battling an illness no one could fathom.

Diagnosing the 'Elephant Man'

Joseph Merrick spent his life believing that an elephant caused his condition. The thought brought him comfort, according to authors Jeanette Sitton & Mae Siu-Wai Stroshane. Merrick inherited the belief from his mother, who subscribed to the idea of "maternal impression," which held that "misfortunes during pregnancy could leave their mark on the unborn child." When Mary Jane Merrick was six months pregnant with Joseph, she got "knocked down in the path of a passing" circus elephant. (Some accounts say the elephant itself knocked her down.) So when she saw a trunk-like growth on young Joseph's lip and "lumpy, grayish skin" develop, she blamed the elephant.

With advances in medicine came new theories about the origins of Merrick's condition. In the 1980s, researchers thought they pinpointed the culprit, dubbing neurofibromatosis Type 1 as the "Elephant Man's disease," a moniker that continued to stick well into the 2000s. But as Gizmodo pointed out, while the ailment results in large cranial growths like Merrick's, it also causes skin spots and epileptic seizures, neither of which Merrick had. DNA tests conducted on Merrick's bones in the 2000s suggest he suffered from Proteus syndrome, but it wasn't a definitive finding. A huge hurdle to arriving at a final diagnosis is that the bones were cleaned with bleach multiple times during the preservation process, rendering much of the DNA untestable.

All of his siblings died young

Joseph Merrick died young even by Victorian standards. A male born in the 1860s was expected to die around age 40, per the U.K. Office for National Statistics. Merrick perished at just 27. Yet he lived roughly as long as all three of his siblings combined. This was a perilous era for children, who often died in infancy. As documented in Measured by the Soul: The Life of Joseph Carey Merrick, two weeks shy of Joseph's second birthday, his brother John succumbed to smallpox at just 3 months old. When Joseph was 8, his brother William passed away from scarlet fever just before his third birthday.

The only sibling to reach adulthood was Joseph's younger sister, Marion Eliza Merrick, who for years had been misidentified as just Eliza, making her fate a mystery. In 2003, the BBC reported that the Rutland Family History Society discovered her full name and tracked down her death certificate. At age 24 Marion died of myelitis, "an inflammation of the spinal cord."

The abusive upbringing of the 'Elephant Man'

In 1873 Joseph Merrick lost the only kind parent he had when his mother, Mary Jane, passed away from bronchial pneumonia. He wasn't yet 11 years old at the time. In an 1884 autobiography (that may have been partly penned by sideshow manager Tom Norman), Merrick called his mother's death "the greatest misfortune of [his] life." Unfortunately, more torment awaited. His father remarried, taking the landlady as his wife. "She was the means of making my life a perfect misery," Merrick wrote.

So hurtful were his stepmother's insults and open contempt that even though Merrick was physically incapable of running, he ran away from home as best he could on multiple occasions. He also walked away from school around age 12 and started working. He found employment as a cigar-maker, but his outsize right hand eventually weighed him down so much that the job became unmanageable. As his condition worsened, so did his job prospects. Merrick's stepmother rubbed salt in his emotional wounds, telling him that he hadn't earned his meals because he hadn't found work. Her biting remarks often drove Merrick to go hungry rather than go home to eat.

At his father's urging, Joseph tried to sell goods door-to-door. His deformity frightened potential customers, who refused to even come to the door. Furious, his father "beat him for failing to earn enough money." Desperate to escape the abuse, Joseph ran away for good.

Joseph Merrick's workhouse woes

It takes a special level of desperation to place yourself at the mercy of a system short on compassion. But a physically abusive father and psychologically abusive stepmother drove Joseph Merrick beyond the brink of desperation. In 1877, he left home. He first found refuge at a boarding house, but luckily his uncle Charles found him. As Merrick recalled in his autobiography, Charles was "the best friend [he had]" in those dire times. Sadly, his new home proved temporary. Merrick attempted to make a living as a salesman, but people were only interested in paying him unwanted attention. Crowds surrounded him wherever he went. Unable to make a living, he decided to live at the Leicester Union workhouse instead.

Merrick's introduction to workhouse life was a "hot bath," which was actually ice-cold. Deemed mentally challenged, he was relegated to performing taxing manual labor like "pulling apart rope and rags with mallet and fingertips." He lived with criminals and alcoholics, and his entire day was tightly controlled. He despised the experience so much that he soon tried his luck at finding a job. Utterly luckless, he returned to the workhouse, where he remained for four years. Meanwhile a mass on Merrick's jaw grew to 8 inches long, hindering his ability to eat. Food would simply fall out of his mouth. So he underwent surgery to "have three or four ounces of flesh cut away."

The 'Elephant Man' sideshow goes sideways

A prisoner of his ever-worsening illness, Joseph Merrick would feel the eyes of onlookers closing in with no hope for escape. For the most part, finding gainful employment was also hopeless because employers couldn't look past his deformity. A four-year stint at a workhouse didn't work out, either. Eventually a kind of Stockholm syndrome set in, and he embraced his disease as a means for survival. "So thought I, I'll get my living by being exhibited about the country," Merrick wrote.

And so he became a sideshow attraction, advertised by managers as "Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant." He would move from Leicester to London in 1884, and carve out his niche as a sideshow attraction. Unfortunately, for Merrick, he couldn't attract people for very long. Decades before he got into the oddity business, people had already predicted the end of "Deformatomania," described by Jane Goodall as a "craze for monster exhibits." The practice appeared to be dying out in the U.K. back in the 1840s. By 1885, gawking at oddities "had fallen out of favor in Victorian England," per the National Genome Research Institute, "and police closed the 'Elephant Man' exhibit."

Merrick took his sideshow on the road, touring Europe. But calamity befell him again when his road manager stole Merrick's life savings and abandoned him in Belgium. All the while his health continued to deteriorate. Merrick somehow scraped by and returned to London in 1886.

The doctors who treated the 'Elephant Man' with kindness

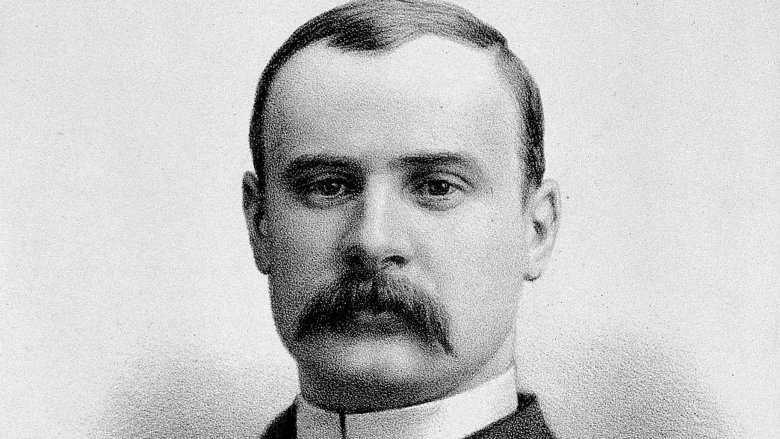

Fans of David Lynch's 1980 classic, The Elephant Man, a film based on the memoirs of Frederick Treves, no doubt remember the heart-wrenching scene in which Joseph Merrick's character gets hounded and surrounded by onlookers at Liverpool Street Station. Trapped in a sea of inhumanity, he unleashes a pained howl before yelling, "I am not an animal! I am a human being!" According to the Guardian, that "horrible" scene was true to the memoirs of Frederick Treves, the physician who befriended Merrick and helped him gain entry to the London Hospital after the train station incident.

It was 1886. Merrick had just returned from being robbed and abandoned in Belgium. He couldn't speak, but he had Treves' business card because the doctor examined him in 1884. Treves decided the best course of action was to have Merrick stay at the London Hospital, but the facility originally refused to open its doors to him because it lacked the means to treat "incurables." Thankfully, hospital committee chairman William Carr stepped in, publishing a letter in the Times newspaper explaining Merrick's situation.

Finally, human kindness won out. Carr's letter elicited an outpouring of support and, more importantly, donations. Merrick lived out the remainder of his life at the hospital. Prominent figures, including the princess of Wales, saw to it that he got to live out his dreams of seeing a theater show and vacationing in the country.

The talented man behind the 'Elephant Man'

When Bradley Cooper starred in a Broadway production of The Elephant Man, people didn't see a chronically mistreated man hampered by deformity but a talented Hollywood hunk who eschewed prosthetics and just contorted his face and body. Critics gave rave reviews, with one praising Cooper for "[making] you believe in the romantic sensibility that existed inside Merrick's distorted frame." But for the real Joseph Merrick, life was quite the opposite. Relegated to life as a sideshow attraction, he spent far more time having people gawk at his head than being appreciated for what was inside it. In fact, Dr. Frederick Treves initially diagnosed Merrick as an "imbecile" because his condition kept him from speaking like a normal person.

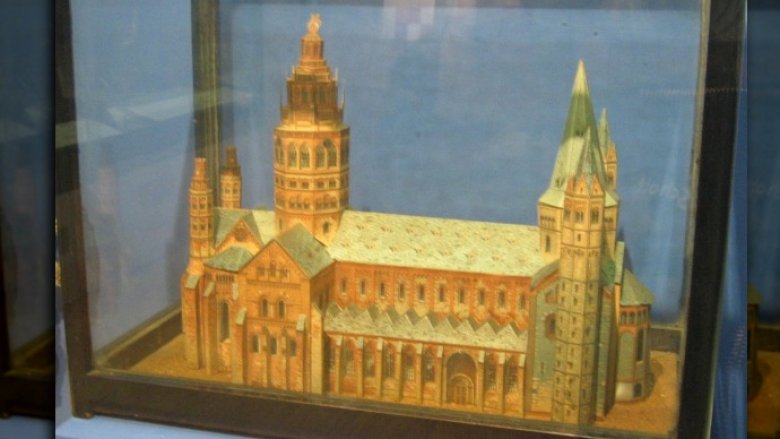

During his days at the London Hospital, people saw what Merrick was capable of. Per Biography.com, he delighted in building replicas of famous places like the Mainz Cathedral (his model is pictured above). Described as "an avid letter writer," he composed prose and poems. He also liked to quote the Isaac Watts poem "False Greatness." The piece starts with a thought-provoking statement, "Tis true my form is something odd / But blaming me is blaming God," followed by the heartbreaking line, "Could I create myself anew / I would not fail in pleasing you." It ends with an oft-forgotten truth: "The mind's the standard of the man."

A very Merrick Christmas

Between losing his beloved mother, being beaten by his father and cruelly ridiculed by his stepmother, enduring workhouse hardships, and being robbed of his life savings, Joseph Merrick probably didn't have many merry Christmases. But during his stay at the London Hospital, he got to witness the goodwill toward men that so often eluded him throughout his life. As recounted in The True History of the Elephant Man, he received Christmas cards, most notably from Princess Alexandra of Wales, who met Merrick in person in 1887 after learning about his plight. He also received various presents. But the gift he gave himself one year really stood out in terms of significance.

The hospital had gotten donations specifically earmarked for Merrick, so Dr. Frederick Treves asked what he wanted. "Joseph showed no hesitation" in his reply, requesting a gentleman's dressing kit. Superficially, it was "useless to him." It contained cigarettes he couldn't smoke with his misshapen lips. It also had "silver-backed hairbrushes and comb, a silver shoehorn and a hat brush as well as ivory-handled razors and toothbrushes," none of which served a practical purpose for someone with Merrick's physical limitations. But as with any gift, it's the thought that counts, and Merrick thought about being "an elegant, sophisticated man-about-town" with a bustling social life, a life he could only enjoy in his imagination.

The debate over burying the bones of the 'Elephant Man'

In 1884 the newly dubbed "Elephant Man" brought his sideshow act to a Whitechapel shop across from the London Hospital. He attracted ample attention from medical professionals, among them surgeon Frederick Treves. Treves placed Merrick on display at the Pathological Society of London but after just one meeting Merrick refused to ever go back. Despite being stared at for a living, he felt "like an animal in a cattle market" in front of all those physicians. Given his visceral response, the thought of placing Merrick's remains in a hospital display case after his death might feel wrong. But that's precisely what happened.

Joseph Merrick's bones reside in a private room at the Queen Mary University medical school, which merged with the London Hospital in 1995. There Merrick serves as an object of contemplation for doctors and students, who can view his remains at a curator's discretion. Per the BBC, in 2016, critics called for the bones to be buried. Valerie Howkins, whose grandfather Tom Norman managed the "Elephant Man," lamented Merrick's fate. "It's just so sad that he had his flesh stripped from his bones and has been mounted in a glass cabinet for 120 years against his will," she said. "He was Christian and would have expected a Christian burial." However, the medical school maintained that he "expected to be preserved."

Michael Jackson's bid for Joseph Merrick's bones

In 1993, King of Pop Michael Jackson sat down with Queen of All Media Oprah Winfrey and accused the press of blatantly lying about him. Among other things, he denied reports that he tried to buy Joseph Merrick's bones, calling the assertion "another stupid story." Where did the press get that stupid story? In 1987, a secretary from the London Hospital Medical College (which owned the bones before merging with Queen Mary University) confirmed that Jackson bid $500,000 for Merrick's skeleton, which the college declined. He previously received permission to view the bones, which even doctors can't freely do.

Not taking no for an answer, the King of Pop upped his offer to $1 million, which Jackson's manager Frank Dileo confirmed. Despite reports that the singer wanted to showcase Merrick's bones in a "chamber of horrors," Delio insisted that Jackson "[had] no exploitative intentions." However, the book Michael Jackson: Grasping the Spectacle argued that Jackson orchestrated a P.T. Barnum-esque ploy to promote himself as a Joseph Merrick-like character living under sideshow-like scrutiny. Perhaps tellingly, he told Oprah he cried while watching the 1980 film The Elephant Man because he "saw [himself] in the story." Moreover, the Grammy Award-winning video for Jackson's "Leave Me Alone" features the singer dancing with a stylized rendering of the "Elephant Man's" skeleton which sports an elephant skull.

The 'Elephant Man' may share a grave with Jack the Ripper's victims

For the last four years of his life, Joseph Merrick called London's Whitechapel district home. Admitted to London Hospital in 1886, he would grapple with rapidly failing health. Meanwhile, Whitechapel's other residents would confront a very different sickness in the form of Jack the Ripper. The notorious serial killer murdered five women "in or near" Whitechapel, per History. Two of the Ripper's victims would share their final resting place with Merrick, at least according to Merrick biographer Joanne Vigor-Mungovin.

While Merrick's bones went to the Queen Mary of London's University medical school, the remainder of his remains mostly went unaccounted for. A sample of flesh was kept "for medical study," and the rest of Merrick was interred in an undisclosed place. Vigor-Mungovin claimed to have unearthed his location in 2019 after searching cemetery and crematorium records. His burial plot "was what we call a common grave," alleged Vigor-Mungovin. Apparently he had that grave in common with Mary Anne Nichols and Katherine Eddowes, both of whom fell victim to Jack the Ripper. If true, Vigor-Mungovin's discovery adds a layer of gore to Merrick's already grim life. But the author saw it as a source of solace, noting that Merrick would have wanted a Christian burial. It appears that part of him may have gotten it.