5 Classic Songs You Didn't Know Were Written For Other Music Legends

Are musicians who don't write their own music actually musicians, or are they mere puppets of record labels, dancing for executives as surely as they dance for the public? We're not quite sure. But, we do know that lots of famous musicians are a step away from being cover artists. For every respected singer-songwriter like Tracy Chapman, history-defining band like The Beatles or superb modern band like Italian blues-and-psychedelia-laced doom outfit Messa (this is a deep cut, people), there's a whole industry within the music industry of artists performing music written by other people. This includes some of the biggest classics of the past century.

By now, lots of us know that some artists, like Lady Gaga and Sia, once wrote music for others before breaking out on their own. In their case, this includes writing songs for the likes of Britney Spears and Beyoncé, respectively. Other songs were originally written for one artist before getting claimed by another. "Holiday" wasn't written for Madonna, for instance, but for Mary Wilson of The Supremes. "What's Love Got to Do With It" was offered to Cliff Richard, Donna Summer, and others before Tina Turner. "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing" wasn't written for Aerosmith but for Celine Dion (makes sense). "Shape of You" wasn't written for Ed Sheeran but for Rihanna. On and on it goes, each as surprising as the last.

But what might be even more surprising is that this isn't a rare or new practice, not by far. Going all the way back to 1967's "Happy Together" by the Turtles, all the way through "Hungry Heart" by Bruce Springsteen, here are some classic songs originally intended for different artists.

Happy Together was written for a bunch of bands

Let's say you're in an unsuccessful band with a questionable future. Most bands, in other words. And because EverTune hasn't been invented yet, you've got to constantly fiddle with your strings. One day, your drummer hears something while you're fiddling, some unintentional melody that you've plucked while tuning. It's strong, tight, and catchy, so the drummer comes to you, the guitarist, and says that your band should make it into a song. You, being an idiot, say no. Then, you hear The Turtles playing that ditty on the radio and calling it "Happy Together." It hits No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1967, right ahead of the famed Summer of Love.

This is precisely what happened when drummer Alan Gordon of The Magicians approached guitarist Allan Jacobs. Jacobs, for whatever reason, didn't want to run with the plucky song, so Gordon developed it with vocalist Garry Bonner. The two made it into a demo and tried peddling it to a bunch of bands, including The Happenings, The Tokens, and The Vogues. They all said no, but the struggling Turtles said yes. Following five failed singles in a row, the band heard the potential in the discarded Magicians track. "It was pretty basic, but you could tell by the melody line it was gonna be strong," The Turtles drummer John Barbata told Uncut.

Not only did "Happy Together" stay at No. 1 for three weeks, but it was also The Turtles' biggest hit. Plus, the song's success brought us the music video with the group's vocalist, Mark Volman, that weird, frolicking French horn guy who looked like Jonah Hill from "Superbad." Not too shabby.

Golden Years was written for Elvis

Is it anything less than utterly bizarre to think that Elvis and David Bowie were contemporaries? Not only is this the case, but David Bowie once wrote Elvis a song. In 1975, right at the end of the Vietnam War and two years before Elvis died at a young 42, Bowie wrote "Golden Years" specifically for him.

From the opening — "Don't let me hear you say life's / Taking you nowhere" — to the three-note on "fine" in the line, "In walked luck and you looked in time / Never look back, walk tall, act fine," Bowie handcrafted "Golden Years" for Elvis' vocal register. You can hear it, too, and easily imagine the King of Rock 'n' Roll's crooning, beefy voice hamming up the lines. Even the subject matter fits Elvis on the tail end of his deteriorating career, which happened to coincide with Bowie's mid-70s rise to fame and heavy drug use. That era started with Bowie's adoption of his Thin White Duke persona — one of his most famous looks — on 1976's "Station to Station." As reported by Far Out Magazine, Bowie told the Daily Express that the persona was intended to be a sad clown "trying to paint the truth of our time." "Golden Years" wound up being the second track on "Station to Station."

At the time, Elvis and Bowie were signed to the same label, RCA, and Elvis' manager, Colonel Tom Parker, thought that the Duke and the King would make a good songwriting pair. By all accounts, Elvis did hear a demo of "Golden Years," but he either passed on it or the collaboration never materialized for whatever reason. And so it is that "Golden Years" became not Elvis' retrospective about the decay and delusion inherent in fame but a vision of Bowie's then-present.

Take Me Home, Country Roads was written for Johnny Cash

Few artists could be so linked to a song as John Denver is to "Take Me Home, Country Roads" (referred to as "Country Roads" from here). Practically every line oozes Appalachian stereotypes — country, roads, mountains, mama, home, rivers, trees, mines, moonshine, etc. — that seem perfectly suited to John Denver. Except it was meant to suit that darkest of deep-voiced singer-songwriters: The Man in Black himself, Johnny Cash.

"Country Roads" comes to us via husband-and-wife folk duo Fat City (Bill Danoff and Taffy Nivert), which released a few records in the late '60s and early '70s. Danoff's original country road inspiration wasn't in West Virginia, however, but in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Also, he was going to use "Massachusetts" in the opening line after "Almost heaven" instead of West Virginia, i.e., the most ungainly, unlyrical word ever. As for Denver, he hadn't even once stepped foot inside West Virginia at the time the song was written, but he did ask Fat City to open for him one night in 1970.

Denver reached out to Fat City to support him at the Cellar Door in Washington, D.C., where Danoff also worked as a doorman. After Denver finished his set the following night, Fat City joined him on stage for an encore, "Country Roads." The crowd loved it, and Denver recorded and released it as his own in 1971. It's not even clear if Cash knew that the song was meant for him, but Danoff knew the song was a potential hit. "The words were pretty; the chorus was nice; it felt good to sing," Country Living quotes him, just as simply spoken as "Country Roads."

Don't Do Me Like That was written for The J. Geils Band

You know what Peter Wolf should have told Tom Petty when Petty went ahead and recorded the song that he intended for Wolf? "Don't do me like that!" If there was a drop of bad blood between them, that is, which there wasn't. That's because Petty, at some point in the late '70s, wrote "Don't Do Me Like That" for Wolf to use with the J. Geils Band.

The J. Geils Band was one of those '70s bands attached to a central figure, like Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Bob Seger & the Silver Bullet Band, and so forth. The J. Geils Band was named after its guitarist, though it was the singer, Peter Wolf, who was friends with Petty. In 1977, Petty and his band opened for the J. Geils Band, no matter that the group eventually overtook the then-headliner in terms of popularity. Wolf and Petty became such good buddies on that tour that Petty penned "Don't Do Me Like That" and mailed it to Wolf on a cassette. "Hey, I think this would be a cool song for you," Petty wrote on the attached note, as Wolf recounted to Rolling Stone. "I think you and the [Geils] band can really do something with it."

To make a long story short, Wolf said he liked the song but didn't want it. Petty wasn't sure about it, but his team talked him into recording it. Petty later thanked Wolf for not taking the song, as it became the Heartbreakers' first Billboard Top 10 hit.

Hungry Heart was written for the Ramones

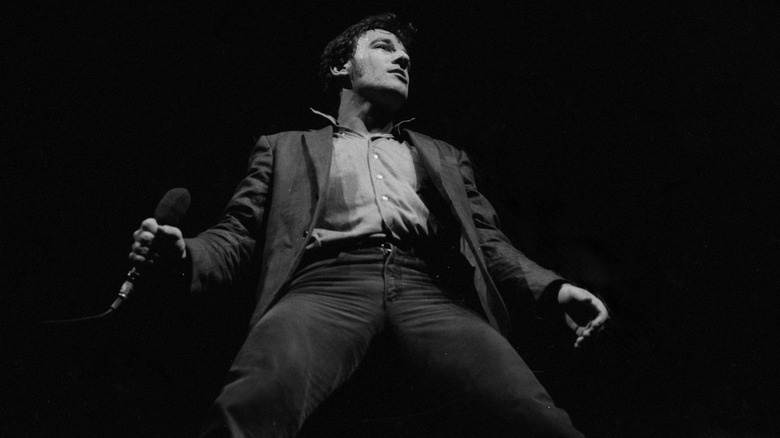

When folks think of Bruce Springsteen, they doubtlessly think of down-to-earth, home-and-hearth, working-class rock. Listening to 1975's "Born to Run" — with the eponymous song being his first Top 40 hit — you can hear how his music was headed in that direction. The same direction that led him to 1982's "Nebraska" and 1984's "Born in the U.S.A." But in between those eras, the Boss (an iconic nickname he hates, by the way) almost gave away a critical piece of his discography, one that he never wrote for himself but for the Ramones: "Hungry Heart."

If it's not possible to hear how "Hungry Heart" was written to be a punk song for the Ramones, it's at least possible to hear how the bouncy, jaunty pop track — one where Springsteen doesn't even need to play the guitar — is an anomaly in the Boss' catalogue. Springsteen met the Ramones in 1979 at a venue where the group was performing, liked the guys, and decided to write a song for them. As he told Howard Stern in late 2024, he went home that very night, scribbled out a song in about 20 minutes, and pitched it to his manager, Jon Landau, who said no. Landau, smartly enough, heard its potential and recognized that Springsteen's poppier songs gained greater popularity. The Ramones never even heard it.

But Springsteen audiences definitely heard it. As Springsteen says in that same interview, his audience was largely confined to young men until he released "Hungry Heart" on 1980's "The River." Not only was it the band's first Top 5 hit on the Billboard Hot 100, but he and his band suddenly became a "date night" band, with women spread throughout the crowd.