The Untold Truth Of Jean Lafitte, The Pirate Of New Orleans

Jean Lafitte–also spelled Laffite–was a man of many contradictions. He was a notorious pirate, but he thought of himself as a privateer, a legitimate officer of a government whose job was to, you know, rob and plunder ships. He was an infamous criminal constantly dogged by local authorities, but he was also a war hero after whom multiple state parks and monuments have been named. He was a traitor and a spy, but he is also a folk hero to people of both Louisiana and Texas. In many ways, Jean Lafitte, the pirate king of Barataria Bay, was the Robin Hood of the bayou.

Nevertheless, the truth about the life of Jean Lafitte is shrouded in mystery, while myths, legends, hoaxes, and forgeries abound. Historians have tried with varying measures of success to separate the true man from the mythos, but here are some things we know–or think we know–about Jean Lafitte, the pirate of New Orleans.

The many births of Jean Lafitte

When you consider the fact Jean Lafitte is one of the most famous pirates in American history, it's pretty wild that we know almost nothing about him. No one knows where or when he was born, for example, but there are plenty of theories. As GoNOLA explains, there a number of locations in France where he could have been born–he and his brother said they were from Bayonne, while the possibly-forged Journal of Jean Lafitte says he was born in Bordeaux to a family of Sephardi Jews that ran to France from Spain after the Inquisition. However, there might have been some cultural cachet and even legal benefit at the time to claim one was from France, and many claim he was actually from Saint-Domingue, or what we now call Haiti. When was he born? "Between 1776 and 1780" is as specific as we can be. People can't even agree how his name is spelled: he himself spelled it "Laffite," but contemporary documents spelled it "Lafitte," which has become the standard spelling in English.

What we know for sure: he had an older brother (probably a half-brother) named Pierre and their mother moved them to New Orleans in 1784, where she married a local man named Pedro Aubrey. From Aubrey, Jean learned the ropes of being a merchant as well as every detail of the waterways of New Orleans.

He ruled a pirate island

As GoNOLA explains, Jean and Pierre Lafitte were raised by different branches of the family and were not reunited until they were adults when they met up in New Orleans. The two brothers naturally decided to go into business together: pirating business. Pierre opened a blacksmith shop that served as a cover for their smuggling operation. Jean did the water parts, leading a fleet of pirate ships to pillage and plunder merchant ships, while Pierre served as the face of the operation, selling the stolen goods out of the blacksmith shop.

Their pirate life hit a brief snag when Congress passed the Embargo Act of 1807 in an attempt to stay neutral in the Napoleonic Wars, by more or less cutting off all legitimate imports from Europe into the United States. This should have been (and was) a good thing for smugglers, but it meant the Lafittes could no longer cover their crimes by pretending to be legit New Orleans traders. And so they did the only natural thing: they started their own pirate colony just down the bayou in Barataria Bay. They had no shortage of recruits as the embargo put so many sailors out of work. With high demand for illegal goods, soon the Barataria pirate colony was booming, with Jean leading the naval operations and Pierre fencing the plundered goods.

Jean Lafitte put a bounty on the man who put a bounty on him

As StMU History relates, the ban on imports caused by the Embargo Act led to a scarcity of resources that Americans had grown used to, and higher taxes meant those goods that did get through were very expensive. The fact Jean Lafitte cut out the middleman by simply stealing these goods directly from the merchants meant he was able to provide New Orleans with the clothes, tools, and food (and, uh, slaves) they were used to at greatly discounted prices. As a result, the Lafitte brothers became folk heroes among people of New Orleans, kind of bayou Robin Hoods. Law enforcement would sort of let the Lafittes slide because of their popularity, and in fact Jean and Pierre Lafitte were only arrested once in their lives, briefly in 1812, but they both soon escaped.

Johnny Law didn't always turn a blind eye, however. NBC News reports on a famous incident of the futility of trying to arrest Lafitte that sounds apocryphal. According to the story, Louisiana Governor William C. C. Claiborne had had enough of the Lafittes' antics and put out a $500 reward for the capture of the beloved pirate. In response, Lafitte put up his own identical ones offering a $1,500 reward to anyone who could catch Claiborne and bring him to Barataria. An extremely Robin Hood move.

He betrayed the bloody British in the Battle of New Orleans

Jean Lafitte went from folk hero to war hero thanks to his role in protecting New Orleans during the War of 1812. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Barataria Bay, where the Lafittes' colony was located, was an important approach to New Orleans, one of the most important ports in the US at the time. The British navy, presumably knowing of the Lafittes' less than amicable relationship with the Louisiana government, sought to gain the pirates' help in navigating the waterways of the bayou. To this end, they offered Lafitte $30,000 (and that's in 1814 dollars, mind you) and a position as a captain in the Royal Navy in exchange for his loyalty to Britain. Lafitte, who was not an idiot, was quick to agree to this offer from the British. Lafitte, who was not an idiot, also had no intention of honoring this agreement.

After telling the British he would definitely cooperate with them, Lafitte made his way to the governor of Louisiana, William C. C. Claiborne, who you may remember as the guy Lafitte supposedly put up novelty wanted posters of as an all-time legendary goof. Lafitte told Claiborne of the impending danger to New Orleans. Claiborne, perhaps understandably skeptical, did not believe Lafitte, and instead of gathering up the troops to protect the port, he sent all his army and navy dudes to wipe out the Barataria colony. Jerk move, Claiborne.

Jean Lafitte, war hero

Even though the governor of Louisiana responded to Jean Lafitte's warning of British invasion by raiding his pirate island, Lafitte still felt confident the United States would ultimately win the War of 1812 (and thought US taxmen would be easier to juke than the British navy), so he figured that continuing to pledge his loyalty to the US was the smartest move for his pirate business in the long run. Since Governor Claiborne had captured some of his ships, some of his men, and a bunch of his money, Lafitte decided to try his luck with another American.

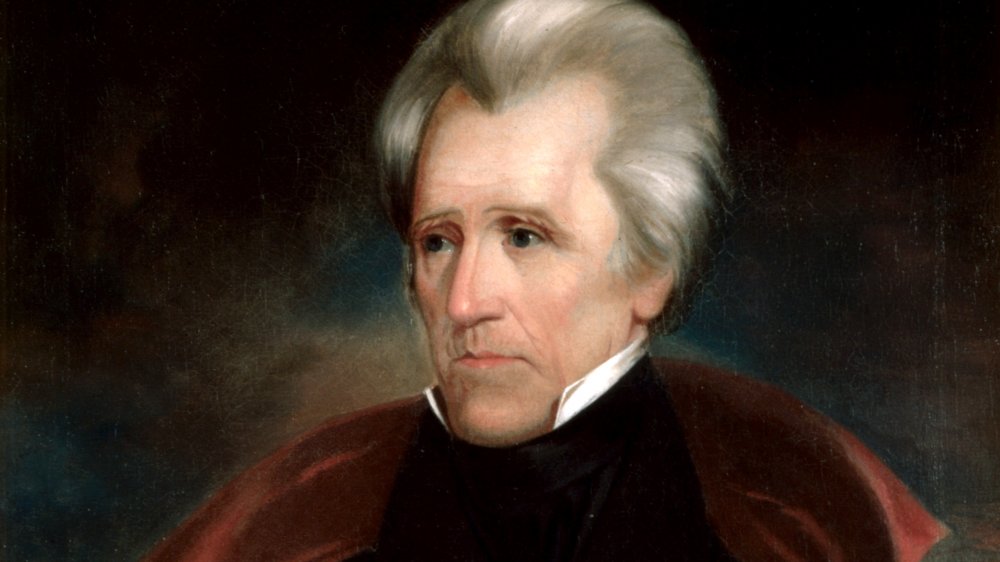

As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, that American was General Andrew Jackson, who took over command of the defense of New Orleans in 1814. Jackson was initially hesitant to work with pirates, and many of Lafitte's men–who you'll remember were mostly disgruntled former Navy seaman laid off due to embargoes–were not exactly enthused to be working for the government. Nevertheless, the Lafittes convinced Jackson to offer full pardons to them and their men in exchange for the strength of the pirates' naval forces. The Baratarians are said to have fought with distinction, and Jackson had to admit Lafitte himself was "one of the ablest men" in the whole battle. Jackson's victory in the Battle of New Orleans won him the fame necessary for him to go on to become one of America's most racist presidents.

Jean Lafitte, secret agent

In 1815, following their victory in the Battle of New Orleans, President James Madison issued a full pardon for Jean and Pierre Lafitte and their Baratarian pirates in a public proclamation. As the Texas State Historical Association explains, the now legit Lafitte went to Washington, D.C. to ask President Madison if he could have the return of his property that had been seized by Governor Claiborne prior to the battle. Presumably correctly reasoning that this property had largely been stolen from the US government anyway, Madison said no and Lafitte returned to New Orleans empty-handed. When he got there, he found out his brother Pierre had signed them up to be spies for the Spanish government against the Mexicans in their war for independence.

In his role as an agent of the Spanish secret service, Lafitte was sent to Galveston Island in Texas, which at the time was the home base of Louis-Michel Aury, a French pirate who was working as a Mexican revolutionary. Lafitte arrived in Galveston just as the revolutionary leaders were leaving the island. Taking advantage of their absence, Lafitte took control of Galveston and appointed his own men as the new leaders of the base. When Aury returned, so many of his men had defected to Lafitte's side that Aury had no recourse but to flee Galveston, leaving Lafitte as the undisputed commander of the island.

He ruled a second pirate island

Since his previous pirate colony had been raided by the government and since he conveniently found himself in command of a completely different Gulf coast island, Jean Lafitte decided to pull up stakes and establish a new colony on Galveston Island. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Lafitte built a new pirates' commune there that he named Campeche, which at its height had thousands of inhabitants, and of which Lafitte himself briefly served as governor. Galveston Island, being a sparsely populated island in the mouth of a bay in Texas, which at the time was itself a sparsely populated area under Mexican control, was an ideal location for pirates looking to operate outside the purview of the US government that had hassled them so much in Louisiana.

Lafitte focused his efforts on amassing wealth from pirating and privateering, but as the Texas State Historical Association points out, he constantly found himself at the center of intrigues among the various European powers who were still vying for control of the Western Hemisphere at that time. He tried without success to betray fugitive Napoleonic generals to the Spanish and schemed with American special agents to reconnoiter the Texas coast. A plan allegedly suggested by President James Monroe was that Lafitte should fake attacks against Texas settlement from the coast to the Rio Grande and then give up the captured land to the US government. Ultimately, this one didn't happen.

Jean Lafitte was lost to history

Jean Lafitte lived a life of luxury in his colony of Campeche on Galveston Island. According to The Islander Magazine, Lafitte's home on Galveston, the Maison Rouge, was the first home of any real substance on the island, having 12 gables, 10-foot arches, a cannon tower, and housing for horses and carriages. Lafitte tried in vain to have his settlement recognized as a sovereign state, but trying to gain legitimacy for a hive of pirates turned out to be a lost cause. Nevertheless, they enjoyed great wealth from their operations, as a visiting American general described Campeche as a flourishing settlement with "gold pieces as plentiful as biscuits."

Nevertheless, nothing can last forever, and by 1819 the end of Lafitte's reign as pirate king was fast approaching. A number of Lafitte's cruisers were captured in open acts of piracy and their crews were hanged. In 1821, the famous warship the USS Enterprise (not the starship) was sent to flush Lafitte out of Galveston. While a number of his men were executed, Lafitte himself was never even arrested. He loaded up his favorite ship, the Pride, with all his loot, set fire to the Maison Rouge, and vanished from history, sailing roughly in the direction of Mexico. The site of what are believed to be the ruins of the Maison Rouge is, of course, haunted and allegedly replete with lost treasure.

The many deaths of Jean Lafitte

There are as many unsubstantiated accounts of Jean Lafitte's death as there are of his birth. Nobody knows for sure how, when, where, or why Jean Lafitte died, but everybody's got a theory. JeanLafitte.net records a litany of these various possibilities. An account from 1885 says Lafitte died of illness on an island off the Yucatan peninsula in 1826, and this idea seems to be more widely accepted than others. The Mexican city of Dzilam de Bravo erected a monument in the spot believed to be Lafitte's lost grave, and legend has it his daughter started a line of blue-eyed Mexicans there. A book from 1837 says Lafitte was killed after his ship was boarded by the British, but the other details of the captain's life in the book are so fantastical that this account can probably be dismissed out of hand.

Another account suggests Lafitte was killed in battle aboard a Colombian ship in 1823 while fighting against the Spanish and subsequently buried at sea. Legends of America also lists the possibility Lafitte died in France or while battling an American warship off the coast of Cuba. The least likely-sounding explanation, however, comes from the incredibly suspicious Journal of Jean Lafitte, which says the old pirate changed his name to John Laflin and moved to St. Louis (notably distant from the Spanish main) and lived into his 70s.

The probably fake Journal of Jean Lafitte

As JeanLafitte.net explains, in 1948, a man named John Andrechyne Laflin went to the Missouri Historical Society with a document called The Journal of Jean Lafitte, which he claimed was the authentic memoir and scrapbook of the famed pirate. Laflin said he himself was a descendant of Jean Lafitte and had found the book in a trunk he had inherited. According to this journal, Lafitte was a Sephardi Jew whose persecution at the hands of the Spanish led to his lifelong hatred of the Spanish (except, presumably, for the extended period in which he served as a spy for them). The book further claims Lafitte changed his name to John Laflin and retired to St. Louis, where he married a woman named Emily Mortimer and had children with her, dying in 1854 as a middle class man in his 70s. The character of the Lafitte revealed in the journal is not the suave pirate of popular imagination, but a moralistic paranoiac who hates the English but loves the Declaration of Independence, and whose professed sympathy for the plight of the downtrodden stands in stark contrast to the historical Lafitte's lifelong involvement in the slave trade.

But while the paper and signature of the journal may appear authentic, the Journal of Jean Lafitte is widely considered a hoax, if for no other reason than John A. Laflin was a known forger of historical documents.

He might have owned the oldest bar in America

The common understanding is Jean and Pierre Lafitte used a blacksmith shop as the legitimate front for their smuggling operations in New Orleans. The building which claims to be that very blacksmith shop is still standing in the French Quarter and is currently operating as a bar. In fact, Lafitte's Blacksmith Shop Bar has a pretty good claim to being the oldest structure in the United States operating as a bar. According to their website, the shop was built between 1722 and 1732 and managed to survive two city-wide fires at the turn of the 19th century thanks to its fire-resistant slate roofing. It is believed the Lafittes operated out of this building between the years of 1772 and 1791 (presumably toward the end of that span, as even pirate king Jean Lafitte was probably not smuggling plundered goods at the age of negative four). It is claimed with perhaps a little more verisimilitude that the building was also owned by one of Lafitte's Baratarians.

As a building of such age and historical interest, Lafitte's Blacksmith Shop is, of course, haunted, with the ghost of Jean Lafitte himself reputed to appear as a full-body apparition, standing in dark corners and staring at patrons. The second floor is said to play host to the ghost of a mystery woman who will whisper your name into your ear.

The search for Jean Lafitte's lost gold

As would certainly be the case with any sufficiently wealthy person who disappeared under mysterious circumstances, there is no shortage of legends surrounding the fate of Jean Lafitte's treasure. In fact, the Louisiana Pirate Festival is based around the legend that when Lafitte abandoned Barataria for Galveston, he left untold riches of gold and silver buried in his favorite hideaway, which has gained the name Contraband Bayou from this belief. Acadiana Historical describes this festival, formerly known as Contraband Days, as a 12-day event held at the Lake Charles Civic Center in May that recreates the life and legends of Jean Lafitte with costumed characters capturing the mayor and making him walk the plank or firing off cannons to ward off enemy ships. The interest in the area is very much centered around the still-current belief the bayou contains hidden riches of the Lafittes, even though no significant finds have been unearthed apart from claims of finding coins here and there.

In 2018, KHOU in Houston reported local men who were told they were direct descendants of Lafitte had put a lot of time and effort into finding Lafitte's ship, the Pride. The men believed Lafitte had scuttled the Pride just outside of Galveston, and with help from the Discovery Channel, they were able to confirm there is, in fact, something big in the water outside Galveston.