The French Murder That Started A Revolution

France has had several revolutions in between monarchies and republics governing the country. The famous revolution, of course, primarily took place during the 1790s and resulted in the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. After Napoleon fell for the second time, France was governed by the monarchic House of Bourbon, until they were also overthrown in the July Revolution of 1830. King Louis Philippe of the House of Orleans then reigned until 1848, according to Britannica.

People are fairly difficult to satisfy when the economy is falling apart. In Louis Philippe's time, there were bad harvests and not enough jobs for everyone, so he had a few problems on his hands. Unfortunately, one of the shining stars of his court, Charles, Duke of Choiseul-Praslin, was about to make it much worse for the French monarchy by murdering his own wife. The murder (as well as Charles' subsequent suicide) was so messy and inept that the ensuing scandal spread far and wide (via GW Law Library). The scandal signaled to the revolutionaries that the king and his court had to go, making the murder a cause of the French Revolution of 1848.

However, just because people are angry with the regime doesn't necessarily mean they know how to build a republic, or that the right man for the job will present himself at the exact right moment. Sadly, that's exactly what happened. The revolutionaries wrote a weak constitution, and their president was ready to overthrow their hard-fought republic for an empire.

A historical note: France in the 1840s

By 1847, King Louis Philippe of the House of Orleans had been king for 17 years. The July Revolution of 1830 had allowed Louis Philippe to seize the throne in the first place, with the assistance of the upper bourgeois, or upper middle class (via Britannica). Though he began his reign by striking a diplomatic middle course, Louis Philippe was eventually forced to abdicate for reform to take place. The king didn't try very hard to hold onto his crown but left nearly immediately with his wife for England, where Queen Victoria assisted the couple by providing them an estate.

There were several revolutions in Europe in 1848. Just as in France, the revolutions dealt with the middle class revolting against the nobility for several reasons — economic depression, food shortages, and unemployment being the main ones, according to Study.com. The French middle class weren't fans of King Louis Philippe, and they intended to inform him. Violently.

The king and prominent members of his court, such as Charles, Duke of Choiseul-Praslin, also happened to get into messy scandals at exactly the right time — for the revolutionaries, that is.

It started with a girl, a boy, and a marriage

Françoise "Fanny" Altarice Rosalba Sébastiani and Charles Laure Hugues Théobald, also known as the Duke and Duchess of Choiseul-Praslin, were married on October 18, 1824, according to author Geri Walton, and had nine children over the course of their 23 years of marriage. Théobald was born a few months after Napoleon Bonaparte became the king of Italy.

The Duchess was Marshal Horace Sebastiani's daughter, who was a distinguished general, according to the Annual Register for 1847. She seemed more invested in her marriage than the Duke, as she wrote about how madly in love she was with her husband in her correspondence. Despite this, their relationship could be explosive, and the Duke had at least one affair, which would add to the upcoming scandal.

Théobald, Duke of Choiseul-Praslin, was a politician as well as a member of King Louis Philippe's court. He served as a member of the Chamber of Deputies from 1838 to 1842 and was named a Peer of France in 1845, according to Honore Fisquet's contribution to the Nouvelle biographie générale depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours.

One couple's marital problems, which led to unexpected murder, would be a cause of an entire country's revolution. History isn't always led by great men or politicians but sometimes by ordinary people simply following their instincts to be nothing but themselves. This series of events seems to prove that emphatically.

It continued with an apparent affair

The English governess for the Praslin children, Henriette Deluzy-Desportes, was reportedly having an affair with the Duke, Charles, by the middle of 1847. The Duchess apparently thought they were going to elope and threatened several times to leave her husband. She also thought, writes Geri Walton, that the Duke had hired the governess to separate her from her own children. The Duchess fired Deluzy-Desportes a few weeks before the Duchess' own murder.

The governess didn't leave Paris but stayed in Le Marais, now known as a historic district. The Duchess had refused to write her a letter of recommendation, which would have enabled her to find another job and possibly leave the city. Though she was brought in for questioning in the event of the murder, she was released and eventually left for New York and married Reverend Henry Field, from Massachusetts, after a few years of teaching.

August 17, 1847

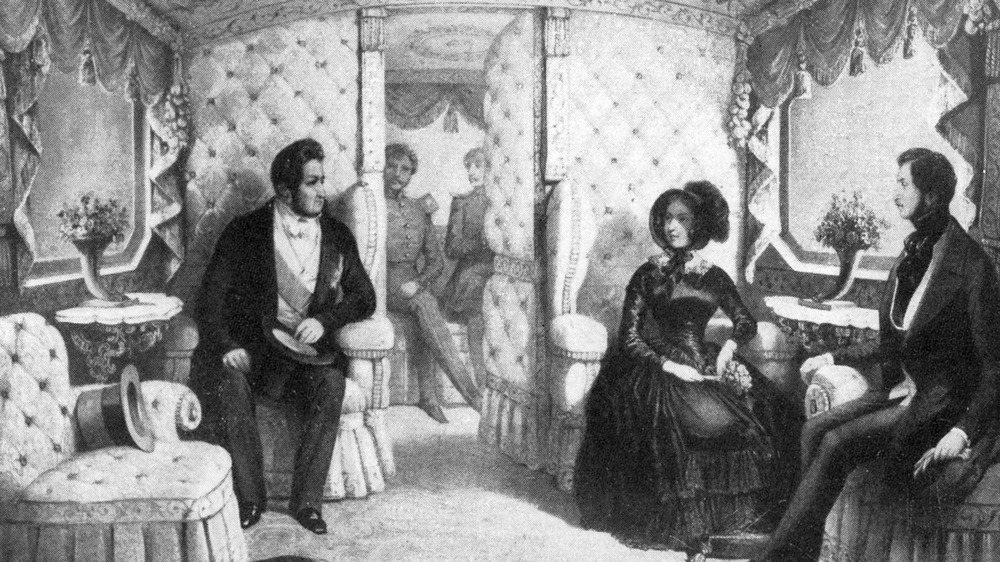

The Duke and Duchess returned to Paris on the Corbell railway after visiting Praslin. The couple separately visited friends before returning to their rooms and were about to take another trip to Dieppe. Their ground-floor rooms were separated by an antechamber (via Geri Walton). At around four or five in the morning, the Duchess' maid heard the bell ring, signaling that her mistress wanted something. The maid rose to assist but found she couldn't get into the Duchess' room.

When, with help, the servants did succeed in getting the door open, they found a horrific sight. The Duchess lay in a pool of blood, with severe wounds at her throat. Her breasts had also been wounded, and one of the fingers of her right hand had been nearly torn off. According to the Annual Register, she was "horribly mutilated and dying of her wounds."

A table was turned over, and porcelain was spread about the room, as was blood. Pieces of hair from the person who had attacked her were scattered around the room, as well as held in the Duchess' fingers. When the Duke was alerted, he immediately came in and embraced his wife's body. Despite surgeons assisting, she died two hours later.

The events of this short night would go on to have repercussions for all of France in the months to come.

Searching for clues

The murder had happened on a Tuesday morning, and police searched for information for several days. Authorities quickly discovered that there was no evidence of breaking and entering, particularly through the garden, which had been closely examined. Blood had apparently been found on the Duke and in his room, according to the Annual Register, though he had embraced the Duchess' body, which would explain where at least some of the blood had to have come from.

The police found out about the Duke's affair with the English governess Henriette Deluzy-Desportes at this stage. Officers began to look for her to start an interrogation. In the meantime, the servants were questioned, revealing that the Duke and Duchess' relationship wasn't as rosy as it may have appeared to be, with the two living separate lives in the same house. It's rare to get an intimate historical portrait of an ordinary marriage, let alone one that affected the country enough to change its entire political climate and fate.

A servant also revealed that he saw a person the same size as the Duke open the window in his room, as if to insinuate that the murderer had made his escape through there to the garden.

The evidence

Due to the supposed affair, and the fact that the Duke and Duchess were living separately at the time, suspicion fell squarely on the Duke, who was arrested and taken into custody. Though everyone who was in the building, as well as everyone who entered, was questioned, only Charles was truly focused on.

Two police officers stayed by his side at all times after this, according to the Annual Register. One of the Duke's pistols had been found, with a ball loaded, and it was also covered in blood and pieces of human flesh. When the servants found the Duke that morning to tell him the Duchess had been attacked, the Duke was reportedly washing his hands, which is, of course, what someone would normally do to remove blood. It's easy to be reminded of Lady MacBeth's famous line from the Shakespeare play of the same name: "Out, damned spot!"

The two halves of a bloodied, broken sword were separately found in the Duke's room and in the garden, as if thrown, The Duke gave no explanation for how they could have gotten that way. On top of it all, Charles was also discovered to be wounded on the hand and leg (via the Annual Register). The evidence was mounting up, and the police had no other obvious leads. The Duchess' murder was so gruesome that everyone wanted the case solved as soon as possible.

Charles, awaiting trial

The mob in Paris who'd heard the rumor that Charles, Duke of Choiseul-Praslin, was the murderer of his wife had the strange reaction of being pleased as well as horrified, simply due to the fact that he was a member of the nobility. Those who hated the king and the aristocrats of his court were perfectly happy to see them caught up in scandal and crime. Charles was so intertwined with the business of the court that his murder trial was jumped forward so as to affect the monarchy as little as possible.

The Court of Peers assembled that Saturday, August 21, according to the Annual Register. After deliberations, the Duke of Choiseul-Praslin was questioned. However, his health was not the best by this point in time, since it appeared that he had taken arsenic in order to commit suicide.

The Duke was promptly given a strong emetic. That same Saturday, he was moved to the prison at Luxembourg. His health fluctuated over the next several days, rising and falling, better and worse. Ultimately, the Duke was found dead on August 24, the arsenic having done its job. Did the Duke commit suicide out of guilt for his actions or fear of having to take responsibility? No one knows for sure.

The Duchess' body lay in state before being buried, while the Duke was buried with little fanfare.

King Louis Philippe

Mainly due to the disasters of the last few years, the middle class did not trust King Louis Philippe or his court. The details of the Duchess' murder were shocking, but to the bourgeois, the Duke as the main suspect was nothing more than another expected outcome for a reign they felt had gone on long enough. The Duke had been allowed to die by himself, by his own hand of poison and suicide, rather than be properly tried as a citizen and presumably be executed. This could not stand. Talk of revolution grew as 1847 faded into 1848.

Strikes and public protests were already banned by the crown, and in February 1848, Louis Philippe prohibited yet another way for the French activists and revolutionaries to shed their anger at the monarchy: Campagne des banquets, which were fundraising dinners held for discussion. As a result, according to Lumen Learning, riots broke out across Paris, and a mob showed up at the palace, forcing the king to abdicate, which he quickly did.

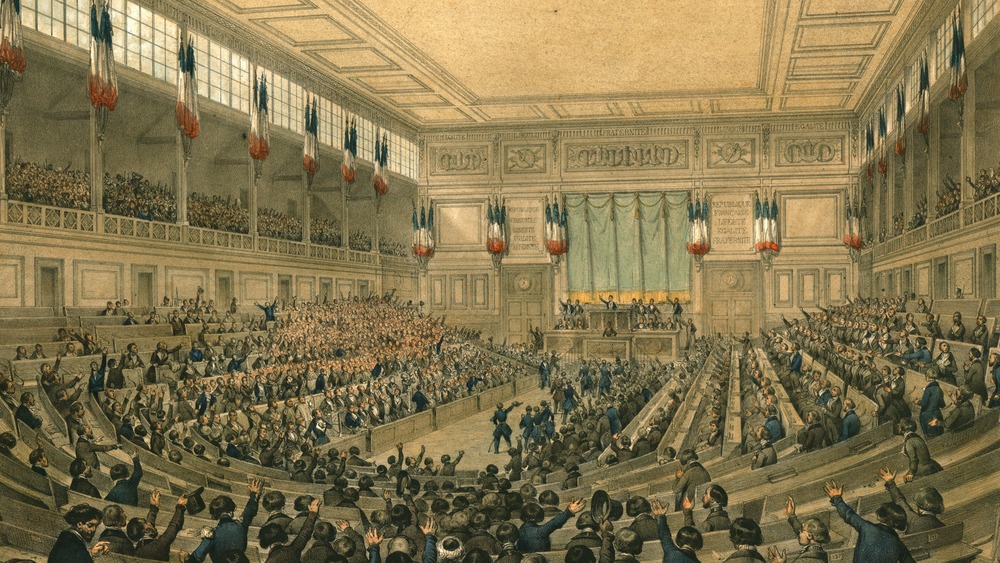

The Revolution of 1848

Louis Philippe abdicated in February 1848, and afterward, the revolutionaries arranged a provisional government. However, the government continued to be disorganized before the elections in April, while strikes increased.

The middle-class bourgeois wanted democratic electoral reforms, while radical socialist leaders such as Auguste Blanqui desired a social welfare republic with the "right to work," writes Lumen Learning. Unfortunately for them, events later that year would ensure that France would never have a social welfare state. The final, large class of people who desired reform sought to steer a middling course.

The revolution brought several different classes together to reform a broken government. Unlike when this had happened in the 1790s, now it seemed as though they had the chance as a people, as opposed to an empire under one man, to figure out how they would run their country. Unfortunately, this would not stand.

The Second French Republic officially adopted the motto "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité." By contrast to that sentiment, the man chosen to be the first provisional president, poet Alphonse de Lamartine, came off as an effective dictator during the three months he was in charge.

June Days

The major goals of the provisional government were job loss relief and universal (male) suffrage. In March 1848, the country gained millions of new voters when it gave all men the right to vote. Government goal complete, France! Political clubs began to pop up all over the country, including for women, though they didn't have the vote.

The country elected mainly moderate candidates in April, as opposed to the liberals who had started the revolution in the first place, according to Britannica. The election results led to a brief insurrection in June, led by workers, which lasted for three days. The government wasn't addressing worker concerns, and they were angry. Some 1,500 workers died, and the possibility of a social welfare republic vanished, according to Lumen Learning.

The provisional government was strapped for cash to pay for social programs that tried to fix the unemployment sweeping the country. It put taxes on land, which alienated landowners (farmers and peasants), and the new taxes were ignored in many rural areas. Uncertainty about the steadiness of the new republic continued to build.

The constitution of the Second French Republic was ratified in September 1848, and it offered very little to assist the Constituent Assembly if there was a disagreement between it and the president. The weak constitution was a clear message that France wasn't ready for a true republic, even if its people desperately wanted one.

France, after 1848

After the revolution that brought the Second French Republic into being, former King Louis Philippe was forced to flee France and settled in Surrey, England. He died there in 1850 (via Britannica). That same December, Charles Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (pictured above) was elected president of the republic.

Also according to Britannica, the Constituent Assembly passed measures in the next few years that trended toward conservatism, such as depriving one third of men their right to vote. As his term came to an end, Bonaparte mainly began to hope for two things: money to pay his debts and a second term. Unfortunately, the Assembly wasn't prepared to pay up, and it became clear to him that he could either step down or stage a coup. Given who his uncle was, it's not that surprising to hear which option he went with...

The Second French Republic only lasted until 1852, since Charles Bonaparte, a nephew of the famous Napoleon Bonaparte, staged a coup, declared himself emperor, and thus dissolved the republic.

When people think of "France" and "revolution," their immediate first response is the storming of the Bastille or thoughts of the guillotine. Though the Revolution of 1848 didn't have quite as much violence, the French people still wanted that change just as badly decades later, and they didn't get it. In the span of a few years, another Napoleon had overthrown everything the revolutionaries had sought to accomplish, and France was once again an empire with one man at its head.