Weird Things About Napoleon You Didn't Know

Given that the guy conquered nearly all of Europe, Napoleon is one of those historical figures we should all probably know a lot more about. But for most of the non-French world, the "Little Corporal" is today nothing more than fodder for jokes about short guys with certain complexes (unfair, given that he was average height, as per ThoughtCo), and yet another cautionary tale for why invading Russia in winter is just a really terrible idea. Mention the creation of the Illyrian Provinces, the Abdications of Bayonne, the Peninsular War, or the Battle of Austerlitz to most English speakers and they'll just shrug.

And while people should know more about Napoleon's achievements, they should definitely know more about the utterly crazy stuff he got up to on the side of his military career. Some of it's mad. Some of it's tragic. And all of it is horribly compelling. Here's some weird things about Napoleon you didn't know.

'Death to the French!' by Napoleon

Most people's mental bio of Napoleon runs to two words: "short" and "French." Which just shows how terrible education today is, because both those things are untrue. While Napoleon would become Emperor of France, he wasn't a Frenchman. He was a Corsican, which is to being French what Scottish is to being English. And, just like any self-respecting Scotsman would his English brethren, Napoleon really, really hated the French.

The site Napoleon.org has a detailed rundown of Napoleon's Corsica years, and it reads like the biography of a raging Francophobe. A small island to the south of France, Corsica was conquered by the French in 1768-69, which is around the same time that Mrs. Buonaparte (as the family name was then spelled) was popping out the future emperor. Napoleon spent his early life on an island under occupation and wound up backing the Corsican resistance. His letters of the time are full of references to French "monsters" and vivid passages about killing Frenchmen.

So, this is clearly raising some questions, such as "what the heck changed?" The answer is: Napoleon's ego got wounded. A one-time friend of Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli, Biography claims Napoleon fell out with the nationalist and took off to France in a huff, refusing from then on to support Paoli. Still, young, nationalist Napoleon would probably have been happy with the direction his older self's life took. The failed invasion of Russia in 1812 killed a ton of Frenchmen.

Napoleon Bonaparte, romance novelist

Look, sometimes a military dictator needs some down time from all that dictating, so why not embrace the arts a little? Adolf Hitler famously produced terrible paintings, Joseph Stalin less-famously produced surprisingly not-awful poetry, so it shouldn't be a surprise that Napoleon had a hidden artistic streak. But the enlightened French tyrant wasn't aiming to capture the sublime in pictorial form, or figure out how to rhyme "roses are red" with "violets are blue." Nah, the general had less grandiose aims. He wanted to write terrible romance.

As The Telegraph details, "Clisson and Eugenie" is the 17-page story of a dashing French military officer who goes around being brave and handsome and the woman he falls for while on a spa break. They have lots of romantic encounters, but the handsome officer (who is called Clisson in the finished version but might as well be called "Bapoleon Nonaparte") is just too darn committed to his warring and is wrenched away from his beloved to fight again. Wow, throw in a scene where Clisson makes love to Eugenie on a bearskin rug in a snowbound mountain cabin and you've basically got a Harlequin novel.

Despite "Clisson and Eugenie" reading like something your grandma used to get herself going before sex was invented, its authorship made it a collector's item. As The Telegraph describes, the current version was reassembled in 2009 from fragments sold to collectors around the globe, most of whom probably paid top dollar. A fool and his money and all that.

He helped pioneer a revolutionary telegraph system

As you might expect from a guy who tried to conquer the whole of Europe in barely a decade, Napoleon was famously impatient. That can be bad enough when you live in an age of instant communication, but for someone living in 18th-century France it was suffocating. When Napoleon joined the French revolutionary army, sending a cat gif from Calais to Marseille involved days of hard riding.

But Napoleon was also a guy who liked to get things done. When faced with a severe communications lag, he didn't just grumble and invade Belgium, he did something about it. That something was pioneering a revolutionary "telegraph" before telegraph technology even existed (via BBC).

"Le Systeme Chappe" was a semaphore system invented by Claude Chappe that involved sticking a pair of mechanical arms atop a tower or mountain and moving them into various positions to signal different things. Another guy on the next tower would replicate those movements to signal further towers, and so on. A basic network was installed by the revolutionary government, but it was Napoleon who expanded it into an international system. Under his watch, the "telegraph" developed until you could send a message from Amsterdam to Venice in mere hours. This was great for the French but less-great for the Italian armies Napoleon could now order crushed from Paris at the drop of a bicorne hat.

Russia wasn't his only crushing military defeat

Napoleon's 1812 foray into Russia is the stuff of humiliating legend. Of the 600,000 or so men who attacked Moscow, fewer than 100,000 made it back alive. The rest, as History details, died the sort of horrible deaths you generally die when temperatures are well below zero, there's no food, you're sleeping inside a dead animal for warmth, and the Russian army is hammering you with cannon fire. What's less well known is that Russia wasn't some crazy one-off. Napoleon had been losing for years by that point.

Take the Leclerc expedition. In 1802, Napoleon sent out a vast French army to retake the rebellious colony of Haiti (then called Saint-Domingue) and reimpose slavery. Tens of thousands of French soldiers sailed off to the Caribbean, only to be stomped by Toussaint L'Ouverture's ill-equipped amateur slave armies and lose France's richest colony in the process. In his podcast on the Haitian Revolution, Mike Duncan said that, were it not for Russia, the Haitian expedition would have gone down as the most embarrassing French military defeat in history.

But, hey, why just stop at land battle losses? There were naval defeats, too! The 1805 Battle of Trafalgar saw Adm. Horatio Nelson completely obliterate the French navy without losing a single British ship. Barely two years later, Napoleon launched the similarly doomed Peninsular War against Spain, which saw over 110,000 French troops fail to take down a ragtag bunch of Spanish peasants (via PBS). By the time Russia rolled around, it's amazing anyone would fight for him.

He once considered using freed Haitian slaves to invade America

The Louisiana Purchase is famous as that time Thomas Jefferson bought Louisiana off the French for the presidential equivalent of spare change. You may know the story behind the sale, that Napoleon was desperate for dough following the loss of his cash crop colony, Haiti. You probably don't know that selling Louisiana was Napoleon's Plan C. Plans A and B involved him invading America, in one scenario at the head of a marauding slave army.

As Slate details, the Haitian Revolution had been a problem for France since 1791. In 1802, though, Haitian leader Toussaint L'Ouverture was still kinda paying lip service to the idea of being part of the French Empire. Napoleon wanted Haiti's sugar money back but couldn't decide between his Plan A of working with L'Ouverture and his Plan B of just invading Haiti. As Mike Duncan noted in his Revolutions podcast, the decision was complicated by Napoleon's dual plan to land a French army in Louisiana. One of the arguments on the side of Plan A was that a mollified L'Ouverture might lend Haiti's slave armies to Napoleon for conquering the Americas.

In the end, Napoleon went for Plan B: land one army in Haiti and another in Louisiana. Unfortunately, L'Ouverture turned out to be really, really good at war, and the French army that went to Haiti got beat so bad that the one headed for Louisiana was diverted to help. When they also got beat, Napoleon just gave up on the whole Louisiana thing, and sold it to Jefferson.

The Napoleon Bonaparte USA retirement plan

A tiny lump of nothing in the South Atlantic over 1,200 miles away from the nearest country, St. Helena is so remote that it didn't even get its first airport until 2016, notes The Guardian. In the early 19th century, it was literally the farthest you could get from civilization without just casting yourself adrift in a boat near Antarctica. It's also where Napoleon spent the last six years of his life in exile after the Battle of Waterloo. But there's an alternative history where he spent his retirement somewhere even more godforsaken than this lump of blasted rock. According to NPR, Napoleon could have retired to New Jersey.

After losing Waterloo, Napoleon had a narrow window of time in which he was a free man, and he used that time planning his escape. Letters exchanged between the First Consul and his remaining allies show he was seriously considering upping sticks and hoofing it to the Land of the Free, where he planned to settle into a life of science, horse rearing, and a whole lotta hunting. Although we don't know exactly where he would've gone, he did have supporters in Texas (then under Spanish control) and Alabama, plus a brother in New Jersey.

Of course, old Bony surrendered himself to the British before his plans could be finalized, but it's still interesting to imagine what the emperor might have done in Tony Soprano's neighborhood. One theory is that he would have raised an army and invaded Mexico. Why settle for only conquering one continent?

His older brother really did retire to New Jersey

The tiny community of Bordentown, New Jersey, is not the sort of place you'd associate with important historical figures. Well, prepare to be amazed, because Bordentown used to be the home of the king of Spain and Naples. Older brother to Napoleon, Joseph Bonaparte had ruled Spain during the Peninsular War before going on the run from France when his brother finally abdicated.

After the debacle of Waterloo, France made a law to ban all relatives and descendants of Napoleon. The Bonapartes scattered, and Joseph ran to America. As the New York Times tells it, he wound up in New Jersey, where he had the exact kind of retirement his younger brother probably wished he could have had. Joseph built a massive house, amassed the biggest library in America, and spent the next two decades palling around with guys like Quincy Adams and, presumably, bragging about his royal status at parties.

Joseph wasn't the only Bonaparte to visit America. Years earlier, Napoleon's younger brother, Jerome, also washed up there and got a woman pregnant. She stayed in America and raised a line of Bonapartes. One of her grandchildren, Charles Bonaparte, became secretary of the U.S. Navy in 1904. The line didn't peter out until 1945, when Jerome Napoleon died in Central Park after tripping over a dog leash (via The New York Times).

South America's revolutionary leaders tried to just give him Argentina

Sir Thomas Cochrane (above) is the real-life action hero you've never heard of. A captain in the British navy, Cochrane often improvised plans on the fly, coming up with borderline insane schemes that somehow worked. During the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon himself christened Cochrane the "Sea Wolf" for his habit of capturing French vessels (via BBC). After he quit Britain following a financial scandal, Cochrane sailed to Chile, where the country's revolutionary leaders handed him the navy and watched as he used it to almost single-handedly liberate Peru.

But there was another side to Cochrane that was less "crazy badass" and more just "crazy." While serving in revolutionary Chile, Cochrane came up with a plan as counterintuitive as it was nuts. Deciding that newly liberated South America needed an emperor, he proposed rescuing Napoleon from exile on St. Helena and just giving him the continent.

Revolutions podcast has a whole episode dedicated to this plan, in all its baffling glory. Cochrane, remember, had previously fought against Napoleon. He must've also been aware that a whole lotta South America already had a supreme ruler named Simon Bolivar. Yet Cochrane tried hard to carry out his plan, and Chile needed his naval expertise so much they couldn't say no. The only thing that stopped Cochrane from handing over Chile and Argentina to the "little corporal" was that he waited until 1821, when Napoleon was dying. His scheme a failure, Cochrane just shrugged and sailed off to try and liberate Greece instead (via Historic UK). (He failed there, too.)

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, starring Napoleon Bonaparte

During his six years on St. Helena, Napoleon was probably the most closely guarded prisoner in history. Not only was St. Helena 1,200 miles from land, it was surrounded by sheer cliffs with only two viable landing spots — which the British had garrisoned with nearly 3,000 men. The Royal Navy had a squadron of 11 ships constantly on patrol, and British garrisons also took over the nearby islands — "nearby" in the St. Helena sense. Tristan de Cahuna is over 1,000 miles away, but the British still armed it. Even Lex Luthor doesn't get put in prisons like that.

The Brits weren't being paranoid. There really were a ton of people out there desperate to rescue Napoleon. Their plans ranged from the dangerously plausible to the patently wacko. (One guy wanted to fly a hot air balloon over from Europe.) But none were as audacious as that of smuggler Tom Johnson. For £40,000, he agreed to rescue the first consul by submarine.

As the Smithsonian notes, this was easier said than done. Practical submarines didn't actually exist yet, so Johnson had to design his own. He planned to surface by the island at night and use a mechanical harness to lower Napoleon down before hightailing it back to Europe. No one knows how far the scheme got, but it wouldn't have worked anyway. Napoleon had rejected leaving St. Helena at anything less than the head of a conquering French fleet, saying it was beneath his dignity.

The Slovenian folk hero

Officially, Napoleon's reputation ain't great. Unofficially, there are a ton of people out there who still don bicorne hats on the weekends and go parading around, pretending to annex their neighbor's yard. But on a government level? Even the French barely teach Napoleon at school. according to Newsweek. There's one country in Europe, though, where pretty much everyone agrees he's a hero: Slovenia.

If you're not up on your European geography, you might be thinking "where?" A strip of land smaller than Wales, Slovenia was once part of Yugoslavia and today is mainly famous for being confused with the bigger nation of Slovakia. But Slovenia wasn't always obscure. When Napoleon took the Austrians to the cleaners in 1809, he turned their province of Slovenia (then called Carniola) into one of his autonomous Illyrian Provinces, making Ljubljana capital of the lot (via Britannica).

Under the Austrians, Slovenian language had been sidelined (via RTVSLO). When Napoleon came waltzing through, he set up local government, allowed it to be conducted in the Slovenian language, and guaranteed safety from reconquest by Austria — at least, until that whole "getting exiled to Elba" thing. Slovenia/Carniola was reconquered in 1813, but by then the cat was out of the bag, and a massive revival of Slovenian folk culture had taken place. Slovenes still credit that revival with leading to their eventual nationhood in 1991.

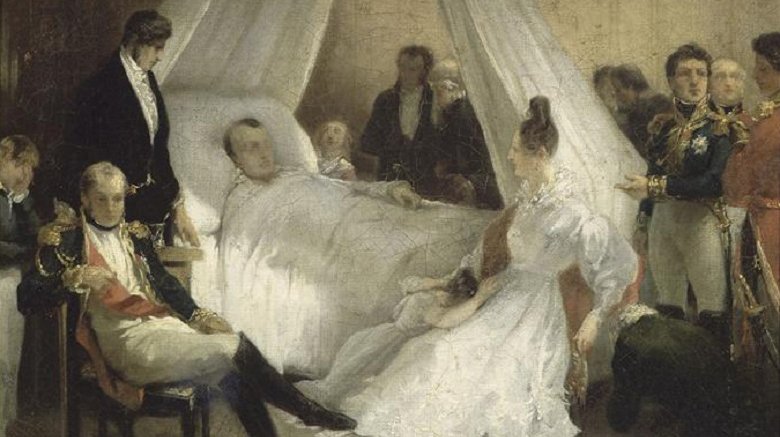

His 'Little Corporal' saw more of the world than he ever did

Despite his endless campaigns, most of Napoleon never saw much of the world outside Europe and St. Helena. We say "most of" because there's one part of the Little Corporal that has allegedly trekked all over: Napoleon's own, um, "little corporal." According to the Washington Post, the doctor who conducted Napoleon's autopsy in 1821 figured one of the perks of the job was taking home souvenirs. When no one was watching, he sliced off the Emperor's scepter and smuggled the little guy back to Europe.

From here, the journey becomes so fantastical it'd seem like fiction, if this wasn't a world where you can get away with stealing a president's brain. The Post claims Napoleon's personal dynamite wound up in the hands (ahem) of an Italian priest, who handed it on to a London bookseller, who sold it to a Philadelphia bookseller, who exhibited it at the New York Museum of French Arts in 1927. Time sent a reporter, who likened it to a "maltreated strip of buckskin shoelace."

Yep, shoelace. Some have suggested that Napoleon's supposed complex was linked to a perceived deficiency in his pants rather than in his stature. Huh. Maybe "Napoleon was small" isn't technically a misconception after all.