What Life Was Like As A Wigmaker In The Colonial Era

Colonial American wigmakers kept busy. It was the style of the times for wealthy men, particularly those with leadership positions in the government and the military, to wear intricate, expensive wigs. Per Colonial Williamsburg, wigs, or "perukes," were often made from horsehair imported from China and served to communicate the wearer's style, place in society, and even occupation. As reported by the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware, other materials included cheaper yak and goat fur as well as human hair, often imported from Europe, where peasant women grew and sold their own hair for export. A wigmaker would have also performed the services offered in a modern barber shop, including shaving and cutting real hair. Measuring heads, offering hygiene products such as powders and remedies for lice, body odor, and other common 18th century issues, as well as reshaping and dyeing wigs for clients as the styles changed were common services. Dyes were made of a variety of substances, including natural animal- and vegetable-based pigments to dangerous metals like lead, mercury, and arsenic.

Wigmakers used "tressing frames" to create wigs, weaving the hair between three strings serving as a small loom. They'd then transfer the woven rows of hair to a head-shaped block molded to the client's measurements and attach it to netting pinned to the "blockhead." Once the wig was assembled, the wigmaker would style it using curling irons, pomades, and dyes, similar to how a modern barber or hairdresser might style actual hair after washing and cutting it.

A modern project to recreate a Colonial wig

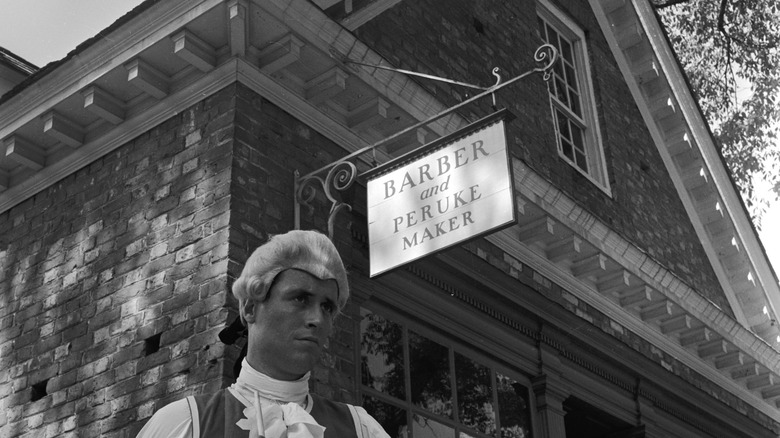

In 2018, Colonial Williamsburg and the Massachusetts Historical Society began a joint project to reproduce a Colonial wig that was part of the Historical Society's collection. It had belonged to a Boston man named Henry Bromfield. Prior to the American Revolution, Bromfield had done business in London as a merchant before returning to his home in Massachusetts and living there until his death at the age of 92. Bromfield was reportedly the last Bostonian to continue wearing 18th century fashions long after most people had moved on to more modern styles. His wig, stored in a coconut, was to be part of a Massachusetts Historical Society exhibit called "Fashioning the New England Family," but the curators weren't sure how to describe the wig. They reached out to the wigmakers at the Colonial Williamsburg Wig Shop (shown above), who traveled to Boston to examine the wig.

Colonial wigmaking was a detailed and arduous process

The Colonial Williamsburg Wig Shop's wigmakers offered to make two reproductions of Henry Bromfield's wig using the traditional methods a Colonial wigmaker would have used: one for the Massachusetts Historical Society and one for the Wig Shop's collection. The project revealed just how much work Colonial wigmakers had put into each wig. Bromfield's wig was a "bagwig," which means its tail was encased in a black silk or satin bag, or "bourse," as shown in the photo above, topped with a large black bow. This was considered a formal wig accessory; for more casual wig wear, Bromfield would have removed the bag and worn it with just a bow.

The Colonial Williamsburg wigmakers sourced gray horsehair like that used in the original, curled it around and tied it to clay pipes, and boiled it to create the curls. They then wove it onto silk netting and hand-knotted the linen base, or caul, which alone took 45 hours. Finally, they sewed the hair to the caul and styled it. The project took a total of 145 hours from start to finish.