The Deadly Heat Waves Of The Turn Of The 20th Century

Heat waves are becoming bigger, badder, longer, and deadlier with each passing year, and in recent memory, they've had some insane consequences. Just take 2012. That's when a high-pressure system moved over the U.S. and then just decided to stay: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says that between June and July of that year, they saw more than 8,000 temperature records tied or broken. Gizmodo says that heat waves are happening more and more often. Fun times! Isn't the 21st century great?

The increasing frequency of heat waves makes it a little strange that they're not really well-defined. A weather pattern is considered a heat wave if an area's temperatures rise above the norm for at least a few days, and that means a heat wave in, say, Maine is about the same as a cool autumn day in Arizona. And that distinction? It's pretty important.

Heat waves are nothing new, and at the turn of the 20th century, a massive heat wave devastated areas in the northeastern U.S., Australia, and the U.K. Thousands of people died, and here's the weird thing: No one remembers it happened. Kind of puts everyday problems into perspective, doesn't it? So, let's take a look at the devastating heat waves that ruined — and ended — scores of lives, and why history has all but forgotten one of the worst weather events in modern times.

The deadliest 10 days

The earth is getting hotter: In late 2021, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released some troubling news that global July temperatures were the highest recorded in 142 years. Today, though, there are things like refrigeration, availability of cold water, and air conditioning to help make it at least a little more bearable, and those are all things that weren't around in 1896.

It was August when the temperature started climbing, and just kept climbing. Ed Kohn, historian, professor of American history at Ankara, Turkey's Bilkent University, and author of "Hot Time in the Old Town" says (via NPR) that the winds died, humidity rose to around 90%, and the temperature on the streets of New York hit 90 degrees. Keep in mind, that's just on the streets — the temperature inside tenement buildings packed shoulder-to-shoulder with people would have been much higher.

A lot of the documentation we have from that time comes from New York City, but the heat wave smothered the entire northeastern United States. The Boston Globe reported: "No warm wave which has visited this country in recent years has held out longer, has been more continuous in its intensity, or more fatal in its results." By the time the heat broke on August 13, people had been dying for 10 days in what the New England Historical Society calls "one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history."

Living conditions made it so, so much worse

A 90-degree day might not seem like an awful thing today, but it's important to remember that there was no refrigeration, no A/C, and no giant frozen margaritas to drink while sitting in the comfortable coolness of a favorite Mexican chain restaurant. Living conditions — especially in New York City — were terrible, and it only added to the misery, says Ed Kohn, author of "Hot Time in the Old Town" (via NPR). Simply put: "There was absolutely no relief whatsoever."

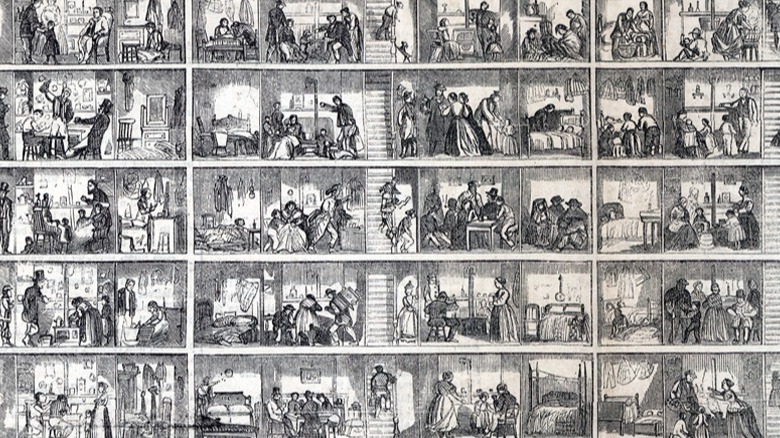

It's worth talking about the conditions that people were living in at the time the sweltering heat swept over the city: At the time, the Library of Congress says that the influx of people into American cities — both from overseas and from the rural U.S. — meant that in the 20 years before the turn of the century, urban populations increased by about 15 million people.

The result was massive overcrowding, and a single room in a tenement building could be home to up to six families. That's right — not individuals, six entire families. History says that in 1900, 80,000 tenement buildings had been constructed, and there were 2.3 million people living in them. There was no indoor plumbing, extra walls and floor meant there was no ventilation, and diseases spread as fast as fire. Add in a city-wide ban on people sleeping in public places — where there would have been at least some relief from the heat — and things went from bad to worse.

People started to die

The first people to start dropping were the outdoor workers, especially those in jobs that were already hot: They were the railway men, the blacksmiths, and the teamsters. They were mostly immigrants, so it was sort of like, "Too bad, so sad." Until, that is, others started dying, too. Stories are terrifying: The New England Historical Society tells of a group of boys who noticed someone "sleeping" in a nearby barn. His name was Patrick Curran, and he had not only died there, but the heat was so bad that decomposition had already set in by the time the boys found him — less than 24 hours after his death.

People collapsed and died while checking on their neighbors, and in 1936, The New York Times reported on the heat wave for the 40th anniversary. They described a scene where scores of horses dropped and died where they fell, their riders dying beside them. In four days, 1,258 horses died, and because the city couldn't handle the bodies, they piled up in the streets.

The search for relief killed more. News reports (via NPR) tell of people who slept outside on fire escapes, only to fall and die in the night. Others slept along the pier, and drowned when they rolled or were pushed into the river. By the time the heat broke, more than 1,300 people were dead in New York City alone.

The first-hand experiences of a future president

New York City's Tenement Museum estimates that for the duration of the 10-day heat wave, the temperature inside the tenements would have been somewhere around 120+ degrees. Iffy record-keeping means that it's impossible to tell how many died there, and it's almost unthinkable to consider that city officials did nothing until they were nine days into the heat wave. Even as The New York Times says morgues overflowed, and ordinary people — like Steve Brodie, who carried ice to fallen and dying horses — tried to do their best, city officials were oddly quiet.

There were few exceptions. The commissioner of public works ordered his employees to work at night when it was cooler, and dump water from hydrants in an attempt to cool the streets. The other was Theodore Roosevelt, then an all but unknown police commissioner.

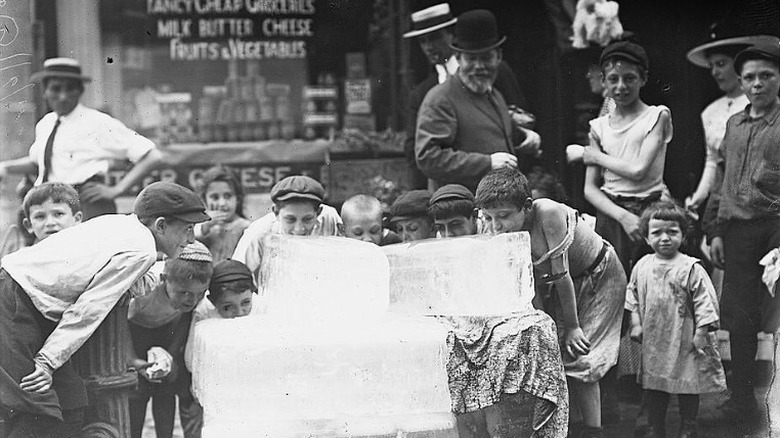

His idea was pretty brilliant, and it involved carting 10-pound blocks of ice to police precincts across the city. The idea was that they were then going to distribute it among the city's residents, but people being people, it wasn't long before Roosevelt found out that law enforcement was charging for the privilege of getting some potentially life-saving ice. Roosevelt wrote of the corruption in his letters, and it's thought the experience inspired him to do more and set him on a road that would eventually lead to the White House.

Charles Morse, the Ice King

It's no secret that people can be kind of the worst, and that's where Charles W. Morse (center) comes into the tale. According to Untapped Cities, Morse was widely known as the Ice King of New York. That's because he saw an opportunity and took it, spending a few years buying ice companies in and around New York City. The rising temperatures of the 1890s meant that local rivers weren't producing as much ice, which suddenly needed to be imported from Maine. Morse was just the guy to do it, and by 1895, he folded all the little companies he'd bought into the Consolidated Ice Company.

When the heat wave of 1896 increased the demand for ice, Morse responded like any shady businessman would, and doubled the price. The skyrocketing prices meant that most of the city's working class couldn't afford ice, and until Roosevelt came along, the results were catastrophic.

Instead of immediate comeuppance, what he actually got was insanely rich. He got out of the ice business in 1901, and while the New England Historical Society says that his name was basically mud, he laughed all the way to the bank — and then bought the bank. Literally. With his controlling interest in a bank, he used funds to buy a steamship company — called the Consolidated Steamship Company — and when that all went sideways during the 1907 financial panic, he found himself in jail and the Federal Reserve was created in the aftermath.

Australia suffered that year, too

Strangely, there was another area impacted by a severe heat wave in 1896: Australia. Climate History Australia says that the country's Bureau of Meteorology didn't start their record-keeping until the following year, so figuring out what it was like required piecing together the bigger picture from various newspapers. They found stories that spoke of people dying from the heat, hospitals that were "full of patients," entire crops that shriveled and died, bushfires that raged out of control, and haystacks that "burst into flames."

The ABC says that the official death toll was 435 people, and adds that the temperature rose to around 120 degrees on at least a handful of the 24-day-long January heat wave. For those three weeks, the temperature never dropped below 100, leading to newspapers — like the Bourke Western Herald — writing sentiments like this: "living in Bourke under present conditions is ... suicide."

Exact temperatures, they add, are up for debate because the process of taking and recording temperatures wasn't standardized until a few years after the heat wave. Still, it's safe to say that simply put? It was insanely hot.

And then, it happened again

The 1896 heat wave was still in relatively recent memory when it happened all over again. On July 4, 1911, temperatures in the same area — across the northeastern U.S. — hit between 103 and 106 degrees, and then stayed there for the next 10 days.

According to the New England Historical Society, the temperature in some places — like Hartford, Connecticut — hit 112, while Cumberland, Rhode Island recorded 130, and one Woodbury farmer had enough when his thermometer rose to 140.

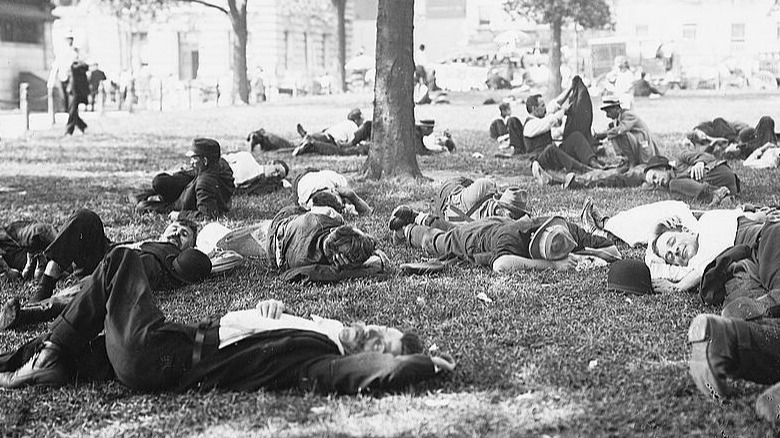

Cities had fortunately learned some very important lessons from the previous heat wave, and bans on sleeping in public places were lifted. Scores of people fled the oppressive heat of indoors — where things like electricity were still considered luxuries — to sleep in public parks. Thousands slept in Boston Common, and those thousands quickly found out that there was a side effect of this: They created a pickpockets' paradise.

Accidental deaths and heat stroke made the headlines

The temperature on the streets hovered around 100 degrees, says History, and record-keeping being what it was, it's hard to tell just how many people died. New York City's death toll was 211, while Philadelphia's was 159, and nationwide estimates are somewhere around 2,000. That's just part of the story, though, and individual tales are as terrifying as they are heartbreaking.

The New England Historical Society says one account described nighttime as a "a giant wail," filled with the sounds of parents who checked on their children to find they'd died in the darkness. There were accounts (via History) of a New York City man who had been driven so delirious from heat that he took a lethal amount of strychnine, while a Roxbury, Massachusetts man killed himself rather than face another day of the heat. Suicides were reported in all major cities impacted by the heat wave.

The heat was so bad that it bent train tracks, enough that it led to the derailment of trains. Hundreds of people died trying to find relief from the heat in local waterways, either drowning or dying as they dove in. There were accounts of people suffering from temporary insanity, too: People stripped and ran through the streets, attacked each other with meat cleavers, and in Hartford, Connecticut, papers reported that it took five people to subdue — and straitjacket — one man who was convinced he needed to climb a utility pole.

Here's what happens to the human body during a prolonged heat wave

Descriptions of people dying by suicide rather than face another moment of heat sounds like the plot of a post-apocalyptic movie, so let's take a closer look at just what's going on here. Does a heat wave have such a powerful effect on the mind? According to Slate, it's a very real danger.

It's no secret that plenty of people get cranky when it gets super hot, but according to a 2011 study from the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, losing just 1% of body mass can change the way our brains work. Keep that heat and dehydration going, and it can absolutely lead to things like hallucinations, delirium, and violent behavior. Those with underlying mental illnesses are particularly vulnerable to extreme changes, and yes, and they have a term for it: Heat-induced insanity. If dehydration and overheating turns into heatstroke, that can lead to permanent brain damage. Those who have suffered heat stroke might have difficulty speaking for the rest of their life.

Because things are only getting hotter, let's touch on some advice from Scientific American. Heat exhaustion can only be treated by hydrating with electrolytes, getting into a cooler place, and resting. By the time it turns into heat stroke, medical attention is needed, and those suffering at the turn of the 20th century? They didn't have any of that.

It even hit the UK and northern Europe

Again, it wasn't just the U.S. that suffered in the summer of 1911. Research published in the Annales de Demographie Historique found a slew of newspaper reports from the U.K., along with other countries across Northern and Central Europe, that paint a picture of abnormally high deaths corresponding with abnormally high temperatures.

It was July of 1911 that the Times started publishing an entire column dedicated to "Deaths From Heat," and according to The Independent, there was ultimately a 20-day streak of hot temperatures and no rain. Much like the news reports on the American side of the ocean, there were heartbreaking stories like the fate of 10-year-old Amy Reeves. She tried to find relief by taking a swim in a local pond, and drowned after getting tangled in the weeds. Fires broke out along the rail lines, crops — and cows' milk — dried up, and the normally lush landscape turned brown.

There's one happy footnote to this, though, as there was apparently one group that absolutely loved the heat wave. It was reported that some of the residents of the London Zoo — particularly the big cats, rhinos, and giraffes that had been sent there from Africa — were "happier than they had been since leaving the large, sunny plains of their homelands."

The bizarre story of the Central Park deer

On July 8, 1911, The New York Times ran a piece that would break the heart of any animal-lover. They wrote that over the course of the previous six days, horses had been dying at a rate of about 10 every hour. Around 600 had already died in the heat wave, and some lay where they had fallen for days before they were removed.

Animals of all kinds weren't doing well in the heat, it was reported, but there was one note about some of Central Park's deer that — while no one should ever try this with their own pet in the heat — kind of gives a little bit of hope with the knowledge that some people do care — a lot.

Some of the park's permanent residents were fallow deer, and as they typically live in cool climates, a man only identified as "Keeper Foley" knew what was going on when he saw them struggling to breathe and stand. He carried them back to his quarters, where he gave them a mix of aconite — also known as the deadly-to-humans wolfs' bane — and brandy. It was then reported, "the deer, when they had tasted of the brandy, winked graciously at Keeper Foley, and resumed their station on four legs." The deer seem to have survived, tended to with cool showers of water and more brandy.

Why have we forgotten about these deadly summers?

The heat wave of 1911 went out with a literal bang: History says that when thunderstorms moved through, the lightning that came with them set fires, then struck and killed at least five people. By the time it was over, NPR says more lives were lost to the heat of 1896 and 1911 than were lost in other, more widely-remembered disasters, like the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, or the earlier New York City draft riots. It seems a little surprising that U.S. history has all but forgotten about these deadly summers, so... what gives?

Historian and author Edward Kohn says (via U.S. News) that there's a few things going on here, starting with the fact that those who died in the heat wave were largely forgettable people. They were the poor, the working class, the laborers who were just one of a score of names on a list. New York City had plenty of those sorts of people, and at the end of the day, they weren't that memorable.

Kohn also says that suffering and death was so widespread that this was simply more of it, and that's a pretty terrible thought. Finally, he says it's also slipped through the cracks of history because there's no big, bold, defining moment. There's no giant fire, there's no damage to property, there's not even anything to really illustrate... just a slow, suffocating death from an invisible and unforgiving force.