The Tragic True Story Of The Great Chicago Fire

Most history buffs—and pretty much everybody in Illinois—know about the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. History explains that for three straight days, the catastrophic inferno burned thousands of buildings. The damage was estimated at $200 million dollars, equal to about $4.2 billion dollars today. Upwards of 300 people lost their lives. According to Britannica, by the time of the fire, the city had grown to nearly 300,000 people, which resulted in a congested downtown area, mostly full of poor neighborhoods. These and other nearby areas would suffer the most damage.

Part of Chicago's trouble with the fire was that almost all structures in the burn area were constructed of wood and crammed close to each other. This was typical of most early towns in America. Like them, Chicago had already suffered its fair share of conflagrations, but the fire of 1871 would be the worst by far. National Geographic verifies that the catastrophe literally devastated the downtown area in the heart of the windy city. Legend goes that it all began in the barn of a Mrs. O'Leary when her cow kicked over a lamp. But the contributing factors to the fire, how it really began, and its effects reach much further than that. Here are some facts about the fire that has become an integral part of American history.

Chicago's early years

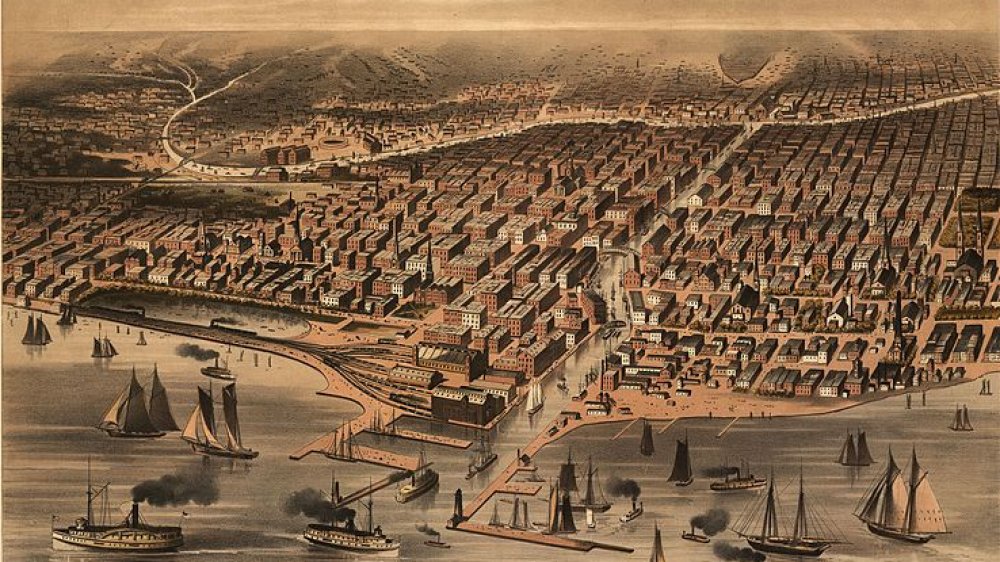

As with so many Midwestern cities, Chicago was originally home to indigenous peoples; according to the city's website, Baxoje, Hoocak, Jiwere, Kiash Matchitiwuk, Nutachi and other tribes made their homes here. It was a matter of convenience, for the Chicago area was "located at the intersection of several great waterways." The Reader explains that the natives called the area "shikaakwa," translated to "Chicago" by the French who explored the area. The early Native trails around Lake Michigan would later become cattle paths and, eventually, roads. That was in the 1770's when Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the son of a French sailor and an African slave, settled on the Chicago River with his Native wife.

In 1803, the American government constructed Fort Dearborn at today's Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive. Smithsonian magazine verifies that early Chicago, founded in 1833, was just a "wilderness outpost" with a population numbering around 350 residents. But the young city grew amazingly quickly, with an influx of people and buildings flying up at every turn. Great Chicago Fire puts it beautifully, describing the early city as "a titanic natural force: unpredictable, unstoppable, all-consuming, and impossible to ignore." The metropolis was not typical in any way. Rather, the city was growing at break-neck speed as a central hub of information, goods, and transformation of the Victorian era.

Chicago's recipe for disaster

The summer of 1871 was tough for much of the country, according to AZ Family. For months, dry, hot, and windy weather had plagued the Midwest. The city of Chicago had seen only five inches of rain in the previous months, half of what normally fell—although Thought Co. says it was actually only three inches since July. Whichever it was, one thing was certain: It was the fifth driest fall season in the history of the city, and Chicago's wooden "shabbily constructed shanties," were being called "firetraps" by the Chicago Tribune. The wood was dry, the weather was hot, and the city was ripe for a fire.

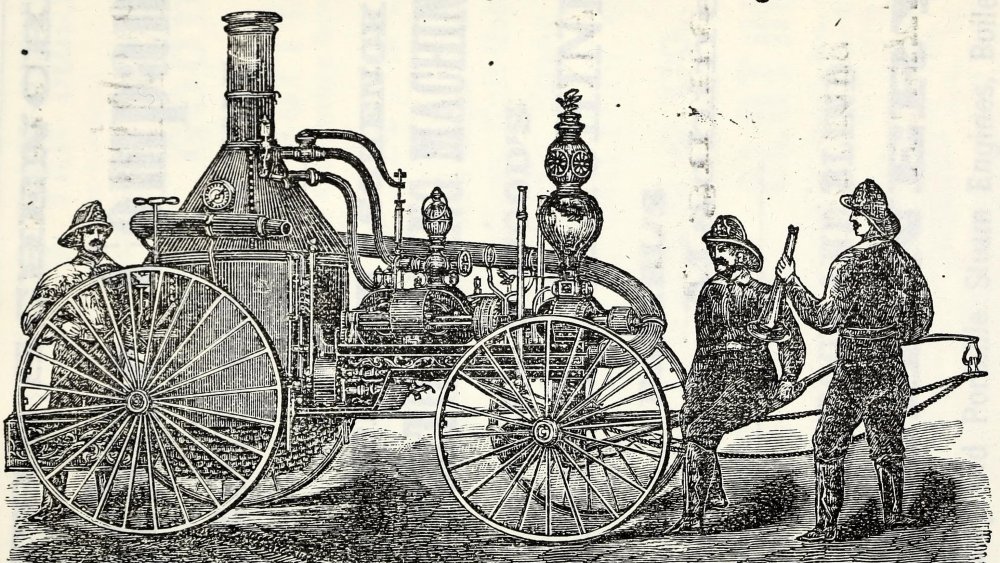

Hindsight is indeed 20/20. The Illinois Library points out that in addition to the dry conditions, Chicago's fire department was grossly under-funded and had actually requested the city hire more firemen, install more fire hydrants, and create a "fire inspection" department. But city officials, fearful that higher taxes to fund the projects might deter growth, declined to implement these necessities. Thus the fire department was constantly plagued with fires—20 in September alone—with only 185 firemen to fight them, according to PBS. On Saturday, October 7, a large conflagration destroyed four city blocks. Little did anyone know that a second, far worse fire was coming the very next day.

Mrs. O'Leary and her rebellious cow

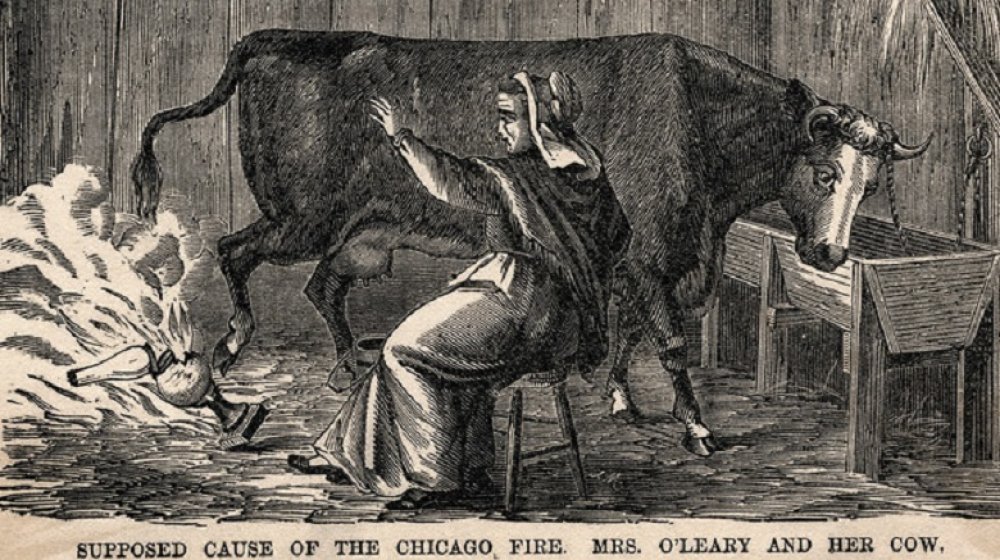

The story of Catherine O'Leary and her cow being responsible for starting the Chicago fire has been told for over a century. The quick synopsis is this, according to sites like History: Mrs. O'Leary was at home (shown here) milking her cow when it kicked over a lamp, which set the barn on fire, which set the city ablaze. Census records for 1870 verify that O'Leary (recorded as "Leary" in 1870) and her husband Patrick were working-class Irish immigrants. They were in Illinois as early as 1856 when their oldest daughter, Mary, was born. The couple had three more children by 1870. Patrick worked as a laborer while Catherine was occupied "keeping house."

Great Chicago Fire submits the story of O'Leary's cow knocking over the lamp is certainly possible. Some said Mrs. O'Leary confessed to the incident. Others claimed to have found broken glass from the lantern in the aftermath of the fire. The Chicago History Museum has a few old cowbells said to have been found at the site. And it is true that the fire began very near the O'Leary home—in the barn in fact—at what is now 558 West DeKoven Street, according to the Irish Times. But wait...the fire began around 8:30 at night. Would a woman be out there milking a cow at that hour?

Did the O'Leary cow really start the fire?

The Chicago Tribune initially jumped all over Catherine O'Leary, calling the 40-something lady "an Irish hag" of about 70-years-old. People needed someone to blame, and poor Mrs. O'Leary made an easy target. Smithsonian magazine cites such incidents as others calling the lady "shiftless and worthless" and referring to her as a "drunken old hag with dirty hands." Circus promoter P.T. Barnum even showed up and asked her to join his entourage. The woman was tormented to no end. But both she and her husband would testify firmly that they were asleep in bed when the fire began.

The Tribune eventually published testimony that one Denis Ryan noticed the fire, alerted everyone, entered the O'Leary barn, and saw hay in the loft burning. But this is just one story. Irish Times says it was Daniel "Pegleg" Sullivan who first saw the flames. Block Club Chicago submits that someone from a party going on next door might have been trying to steal milk and started the fire. Not until 1911 did journalist Michael Ahern claim it was he who started the rumor about Mrs. O'Leary. And it was 1997 before the Chicago Committee on Police and Fire exonerated the lady of all wrong-doing. The real cause of the fire remains unknown.

Chicago, 'Garden City of the West,' burns

That's right. Prior to the Great Fire, Chicago was indeed referred to as the "Garden City of the West," according to U.S. History. But the city's lovely parks and gardens perished in the burn path as miscommunications and confusion became the plague of the day. City officials did know this much: the already-exhausted firemen were initially sent to the wrong place as a storekeeper at the right place pulled at a new fire alarm box, only to find it didn't work. It was at least an hour before seven fire companies arrived, according to PBS, but the flames were already out of control.

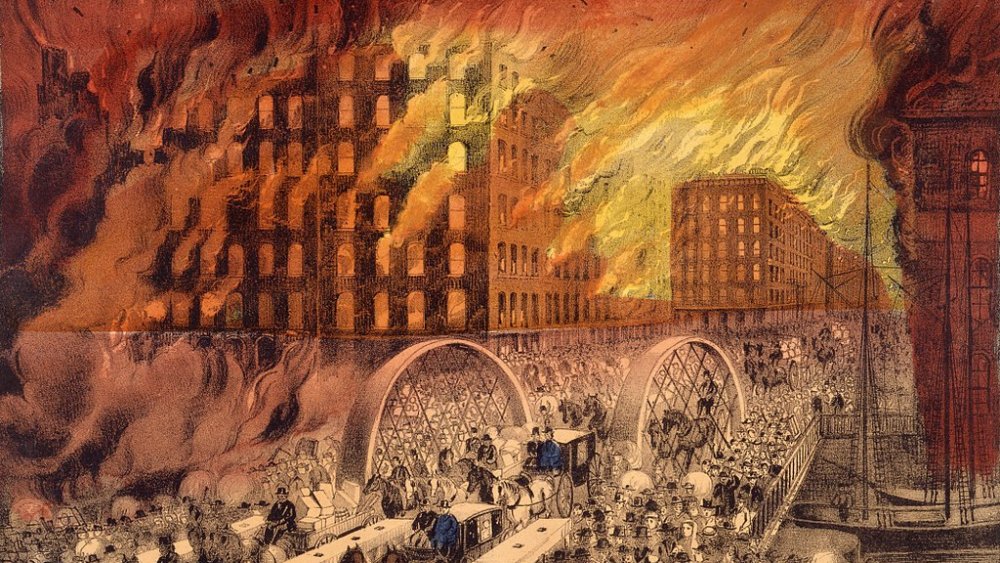

As word spread about the fire, the winds kicked up and fanned the flames further. Wooden buildings, sidewalks, coal yards, warehouses, and lumber yards fueled the conflagration as it leapt over the Chicago River and embers lit on the South Side Gas Works, which blew up. The courthouse caught fire and the great bell tower collapsed with a ringing thud heard a mile away. Mass panic ensued as residents fled in terror and Mayor Roswell Mason placed the city under martial law, according to Legends of America. When the roof of the water pumping station collapsed on early Sunday morning, all efforts to douse the flames were lost. The fire would rage for another day and a half.

First-hand accounts of the fire

Author H.A. Musham would later write, "Every one of the 334,270 people in Chicago on those fateful days had a story to tell, and they never tired of telling it." The Great Chicago Fire was an amazing moment in history, and telling their stories perhaps gave people relief. One of the first reporters to write about it was illustrator John Chapin of Harper's Weekly, who recalled hearing a commotion from his room at the Sheridan House. "I rose and went to the window," he said, "and gazed upon a sheet of flame towering one hundred feet above the top of the hotel, and upon a shower of sparks as copious as drops in a thunder-storm."

Others echoed Chapin's account. Alexander Frear recalled hearing people "singing in the Methodist church" as he "noticed the glare of the fire on the West Side" at Randolph Street (shown here after the fire) and Clark Street (per PBS). Chicago Tribune editor-in-chief Horace White remembered that "a column of flame would shoot up from a burning building, catch the force of the wind, and strike the next one, which in turn would perform the same direful office for its neighbor." Mrs. Alfred Hebard of Iowa was just passing through Chicago, but fled with others across State Street Bridge "amid a shower of coals... The crowd thickened every moment; women with babies and bundles, men with kegs of beer—all jostling, scolding, crying, or swearing."

Heroic rescue efforts

Many a hero was born of the Chicago Fire, although many of their stories have been lost to history. Not only would 300 people die (William Carter remembered people rushing into "traps and places where they were soon surrounded and no retreat left"), but also another 100,000 were left homeless, according to All That's Interesting. Rescue stories came in snippets, such as one tale about an unnamed Irish lass who was taken to the Sherman House (shown here after it burned) "with her dress nearly all burnt from her person" after it caught fire from a cinder at the courthouse. Some even fled the oncoming flames "carrying cats, dogs and goats," said one man, while others frantically "saved worthless things and left behind good things."

Perhaps the most admirable rescue attempt, according to Chicago Magazine, was at the city jail below the courthouse. The prisoners screamed for help when smoke began filling the place. As folks tried to free them, a callous county official told them only the mayor could order their release. Upon hearing about it, Mayor Mason quickly scribbled a note ordering the prisoners' to be freed, "keeping them in custody if possible."

But such an action was nearly impossible. Not until Monday morning, day three of the fire, were officials able to begin gathering supplies, outlaw price gouging, and telegraph for help. They received some five million dollars in aid from all across the world.

After the fire: a city in ashes

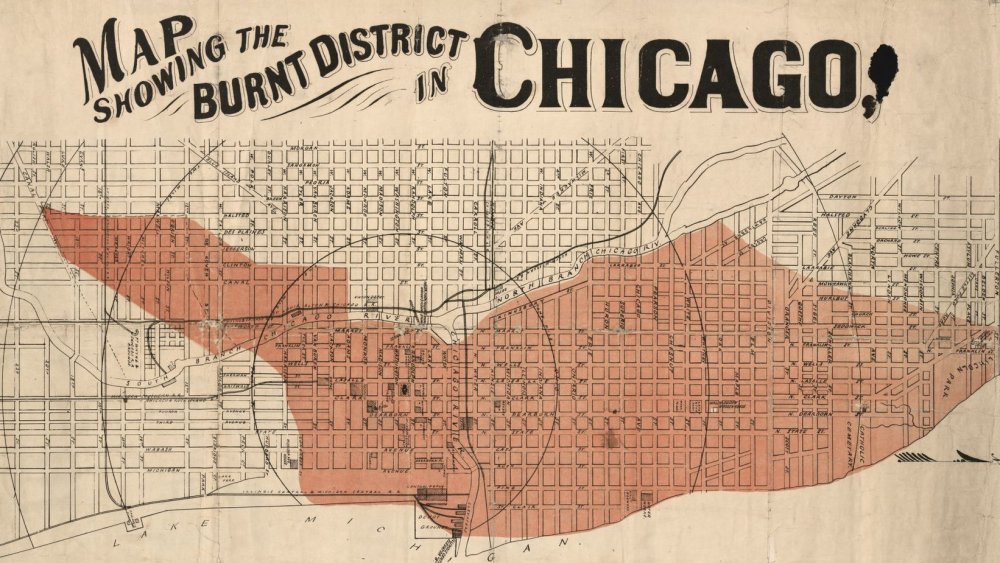

Well, not the whole city. The flames finally became manageable after rain at last fell on the city on October 10. Chicago Architecture Center points out that only 2,100 acres spanning four miles long and about three-quarters of a mile wide burned in total, missing some of the city's major industries, which would help Chicago rebuild quickly. Historian Tim Samelson was quoted by Block Club Chicago as explaining that "The West Side, except for a little area around the O'Leary house, was mostly intact." And while most of the downtown area burned, other large sections of the city escaped damage.

This is not to say that Chicago emerged virtually unscathed. In fact, the burn area remained so hot that it was days before the damage could be assessed, says Great Chicago Fire. Miraculously, some businesses found their safes still standing in the midst of their burned buildings. While many neighborhoods burned, some homes—including the Ogden Mansion on today's Walton Street and a policeman's home on Hudson Street, remained unscorched. Amazingly, even the O'Leary house (but of course not the barn) survived. Approximately 18,000 other buildings did not. And many had been occupied by Chicago's poorest people whose fire insurance policies, if they had one, had burned—or else the insurance companies themselves had succumbed to the fire. They would never recoup their losses.

There were four other catastrophic fires on the same day

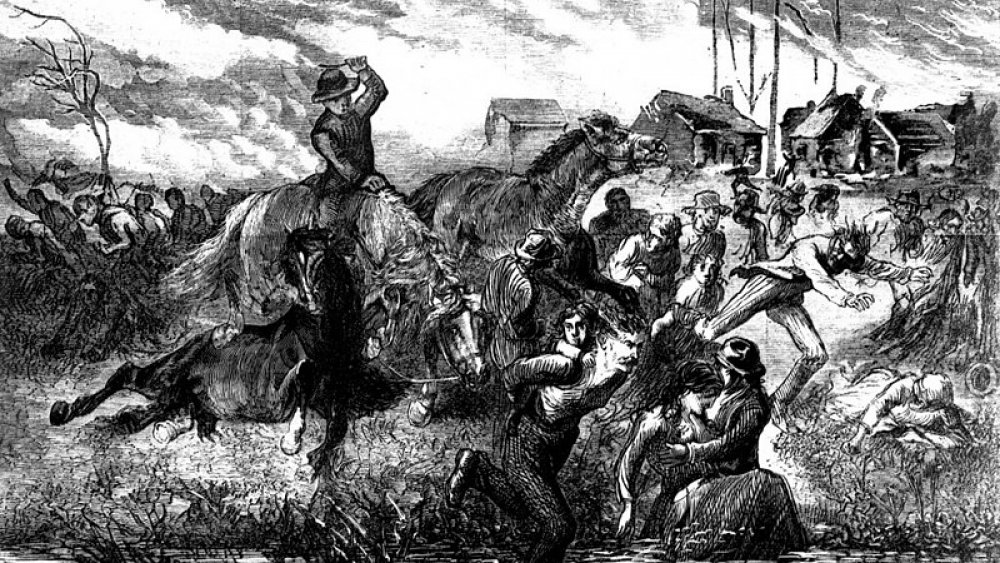

It is most interesting, and important, to note that four other fires in the Midwest also erupted on October 8, 1871. And the Chicago fire was not even the worst of them. So why is the Chicago fire more famous? "Part of it is that myth of the cow—Mrs. O'Leary's cow tipping over the lantern," said University of Wisconsin-Green Bay Area Research Center archivist Debra Anderson (per the National Weather Service). Anderson also noted that Chicago was the largest city to burn. The other four fires were the Peshtigo (pictured) in Wisconsin, and the Holland, Port Huron, and Manistee fires which all occurred in Michigan, says Gizmodo. Historically speaking, the Michigan fires have been lumped into one, called the Great Michigan Fire.

Only the Peshtigo fire has any link to the Great Chicago Fire: William Ogden lost his home in Chicago, but also his lumber holdings near Peshtigo. In the latter instance, Fire Engineering reports that 2,400 miles comprising 1.5 million acres swept through the forests in northeastern Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. It is just a guess that between 1,200 and 2,500 people died, since many of them were lumberjacks or railroad and factory workers who lived in 16 or so remote camps. Eight hundred victims lived in Peshtigo, roughly half of the town's population in 1870. And although the exact number of victims in the Great Michigan Fire remains unknown, it is estimated that over 500 people died.

Mayor Roswell Mason was a hero

In 1998, the Chicago Tribune reported that the Chicago Historical Society was fortunate to receive Mayor Roswell Mason's hastily scribbled note reading, "Release all prisoners from jail at once, keeping them in custody if possible." Mason's great-great-great-great granddaughter, Caroline Thompson, notes that her ancestor was elected in 1869 as the city was already wrestling with "gambling saloons, brothels, and crooked councilmen." Mason, who was generally liked by citizens, was called "an honest man presiding over a den of thieves." True to his demeanor, Mason dared enter the courthouse as it began burning and sent urgent telegraphs for help. "Before morning one hundred thousand people will be without food or shelter. Can you help us?" he queried to officials in Milwaukee and Detroit.

By October 12, the Chicago Tribune was publishing news of the donations pouring into Chicago because of Mason's urgent requests. That same day, according to Chicago Now, Mason turned everything over to the Chicago Relief and Aid Society. Coincidentally, 1871 was an election year. An exhausted Mason declined to run again, but the office went to Joseph Medill (pictured) two months after the fire. Mason, meanwhile, remained in Chicago and died in 1892.

New laws require building in brick

Chicago was unfortunate in that the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company had yet to create a map documenting the layout of the city. Founded in 1867, Sanborn maps meticulously laid out every building on every lot along every street in American cities. They were expressly designed to be of use in the event of a fire—but Sanborn hadn't gotten around to making a map of Chicago by 1871. City officials made do instead with an 1868 Guide Map of Chicago created by Rufus Blanchard. The document was enough to guide officials as they figured out what had been where before the fire (and Sanborn would not generate a map of Chicago until 1894). And a subsequent map generated in 1871 pointed out the burn area, which is a boon to historians today.

Officials also decided to rewrite the building codes for their city. National Geographic reports that all new laws were passed requiring structures to be built of brick, limestone, marble, or stone. This created a problem for those who could not afford such materials, resulting in some businesses and residents being "crowded out of Chicago." Others simply ignore the laws and rebuilt with wood. But the brick industry in Chicago boomed, according to Chicago Reader. Two-thirds of the building permits during 1872 were for brick structures. Also, a series of brick plants sprung up, using the clay from the banks of Lake Michigan.

A bigger, better city of Chicago

Already a veteran of the Chicago Tribune, mayor hopeful Joseph Medill managed to find a way to publish a rousing, encouraging editorial on October 11. Medill's column appeared on the front page under the headline "CHEER UP." The none-too-brief article stated that "Chicago shall rise again," and talked of the "blessed charity" that would prevent citizens from suffering "from hunger or nakedness in this trying time." Rail service had been unaffected. Trains filled with supplies were coming, contracts were being made for rebuilding, the banks were safe. "Let us all cheer up, save what is yet left, and we shall come out right," Medill promised.

Medill's article almost seemed like a campaign speech, and it probably was. Although History submits that his victory might have been propelled since the voter records had burned and "it was next to impossible to keep people from voting more than once," the man was sincere. And luckily, much of Chicago's infrastructure had not been damaged. Chicago historian Neal Samors even theorized that without the fire, Chicago "would probably have been a much smaller metropolis and not the second largest city in the United States." But the modern architectural wonders implemented proved to be a big draw. Within nine years, half a million people called Chicago home. By 1891, there were a million. Today Chicago has indeed risen from the ashes—and notably, Chicago's Fire Department Training Academy is located on the site of the O'Leary home.