The Native American Fish Wars Of The 1960s And 1970s Explained

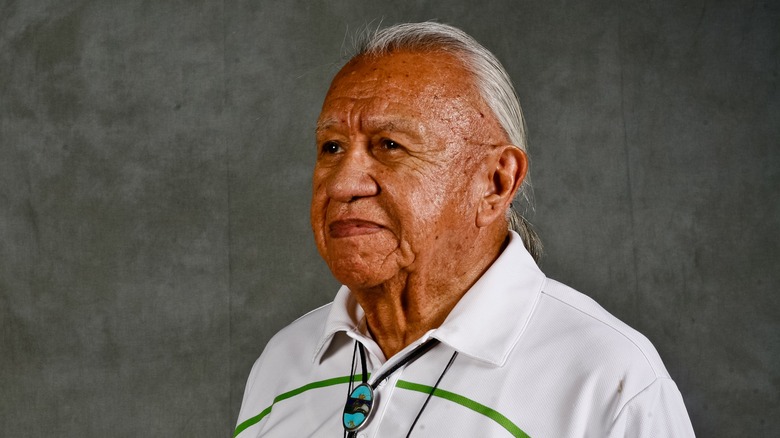

When American settlers assumed control over the Pacific Northwest during the 19th century, they largely did so through treaties. However, Don Ivy, Chief of the Coquille Indian Tribe, underlines the fact that none of the treaties actually came out of a real negotiation. "It was essentially Indian people being compelled to sign this with a promise that no harm will come your way. Don't sign it and all bets are off." And because some Indigenous people, like the Lushootseed people, "organized themselves by town instead of by a tribe with a formal political leader, some communities were left out of the [treaty] negotiations entirely."

But as it soon turned out, the Americans who'd insisted on the importance of signing treaties cared little about upholding the treaties, and for over a century, Native rights were infringed upon. This oppression ended up culminating in the Fish Wars, where fishers in Washington protested for their Indigenous right to fish on their lands, as underlined by the treaties signed by the federal government.

The Fish Wars led to a change in the conversation about tribal sovereignty and treaty legality. And many of the activists that participated in the Fish Wars, like Ramona Bennett, went on to become prominent members of the fight for Indigenous rights in the 1960s and 1970s during the Red Power movement. This is the Native American Fish Wars of the 1960s and 1970s explained.

Local treaties

The United States government started partitioning out land in the northwest before they could even justify a legal claim to the land. The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 provided over 300 acres to any white American man, an early version of the Homestead Act. And although the act was passed before any treaties were signed, Congress also passed an act authorizing the negotiation of treaties with Indigenous groups "for the Extinguishment of their Claims to Lands lying west of the Cascade Mountains, and for other Purposes."

Between 1850 and 1852, Indigenous tribes in the northwest of the United States signed up to 20 treaties with Anson Dart, Superintendent for Indian Affairs in the Oregon Territory. However, none of these treaties were ever ratified by the Senate. The Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest notes that the ratification of these treaties was opposed by Oregon's territorial delegates. Known as the Anson Dart Treaties, according to Trail Tribes, these treaties were signed with the "Clatsop, Wau-ki-kum, Konnaacc, Kathlamet, Klatskania, Wheelappa, and Lower Chinook bands of the Chinook peoples, as well as the Tillamook and other bands."

OPB reports that what often happened was that Indigenous people moved to the area designated by the treaty, thinking that they had a binding agreement, "and then money never came from the Congress because the treaty was not ratified."

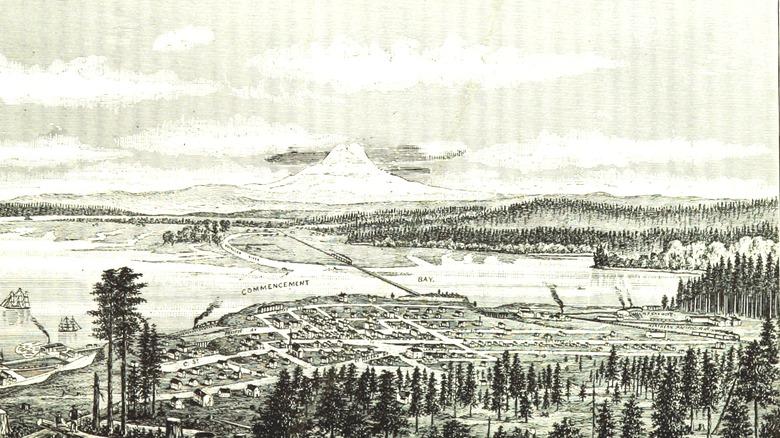

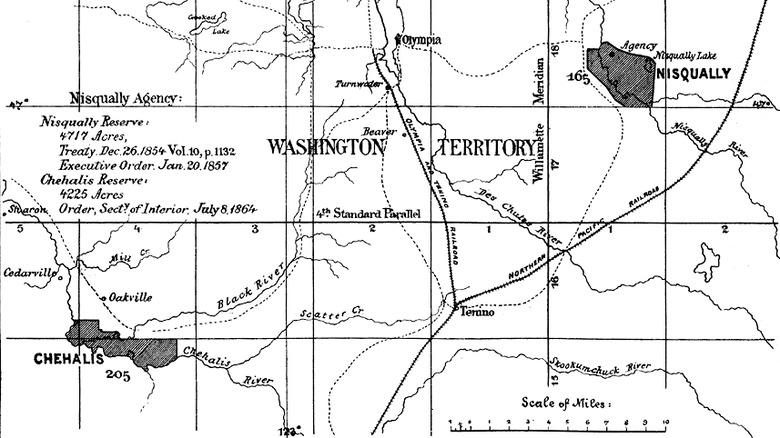

Washington territory

After Washington Territory was created in 1853, several treaties were signed with Native people, including the Treaty of Point Elliott, the Treaty of Medicine Creek, and the Point-No-Point Treaty. The Counter writes that with these treaties, Indigenous people were restricted to reservations and given paltry cash sums in exchange for millions of acres of land. However, these treaties also included the "right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians, in common with all citizens of the United States." This clause was reportedly essential and many tribes wouldn't have signed treaties without it.

Nevertheless, many still expressed concern over the treaty provisions, like Skokomish leader Hool-hol-tan. According to History Link, Hool-hol-tan specifically underlined the issue of food accessibility. "Our only food is berries, deer, and salmon. Where then shall we find these? I don't want to sign away my right to the land. Take half of it and let us keep the rest. I am afraid that I shall become destitute and perish for want of food."

These treaties were negotiated by Isaac Ingalls Stevens, the first governor of Washington Territory. And although he "personally assured [Indigenous people] of the validity of the documents," it took the United States up to five years to ratify the treaties. And even after being ratified, payments and benefits guaranteed to Native people in the treaties were often "delayed or forgotten."

Pre-war treaty violations

Because the treaties took years to be ratified, Native tribes who moved to reservations didn't receive the annual federal payments that were required by the treaties. Some, like the Duwamish people, weren't even given a specific designation of land. Instead, "federal officials and local whites pressured Cuwamish residents to join other tribes on the Port Madison, Tulalip, and Muckleshoot reserves," according to "Legal Codes and Talking Trees" by Katrina Jagodinsky.

Meanwhile, some, like the Nisqually and the Puyallup, realized that their reservations "would constrict their access to their fishing and gathering grounds." Governor Stevens refused their request for access to better-situated lands and Zoltan Grossman writes in "Unlikely Alliances" that his refusal led to the Puget Sound War of 1855-1856, which was fought by the Nisqually, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Klickitat against the United States.

The Yakima War, which lasted from 1855 to 1858, was also in response to treaty violations. After gold was discovered in Washington State, "miners stole horses, murdered Indians, raped women, and violated the provisions of the Yakama treaty." According to "Forgotten Voices" by Clifford E. Trafzer, the United States federal government never addressed these violations. The Yakima were also joined by the Palouse, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Coeur d'Alene, and Spokane people in their fight against the United States. During the Yakima War, Chief Leschi of the Nisqually was found guilty of murder and executed, despite the fact that a lawful combatant can't be charged with murder during wartime, per The Seattle Times.

Post-war treaty violations

After the Puget Sound War and the Yakima War both ended with an American victory, the land grab continued. Land that was meant to be within the boundaries of the reservations kept being appropriated and, according to OPB, eventually the Dawes Severalty Act "turned their land into a patchwork of small allotments, privately owned by both Indians and non-Indians." Meanwhile, according to "The State of Native America," edited by M. Annette Jaimes, Native people were arrested for fishing in the early 20th century, "even on their own federally-supervised lands."

Indian Country Today reports that in 1917, the United States Army occupied Nisqually reservation land and by 1920, the title of over 3,000 acres of Nisqually land was appropriated by the United States Army for the Camp Lewis base. History Link writes that although Pierce County had no authority to acquire Nisqually land through condemnation, Pierce County Superior Court Judge W. O. Chapman, who was also conveniently part of the condemnation proceedings, "ruled that legal precedents made condemnation of the reservation lands legal."

The Seattle Times reports that Washington also closed six rivers to salmon fishing in 1889, the first year of its statehood, and all six rivers were fishing grounds used by Indigenous people. "The state eventually banned net fishing in all rivers, except the Columbia, effectively outlawing the Indians' main way of catching fish."

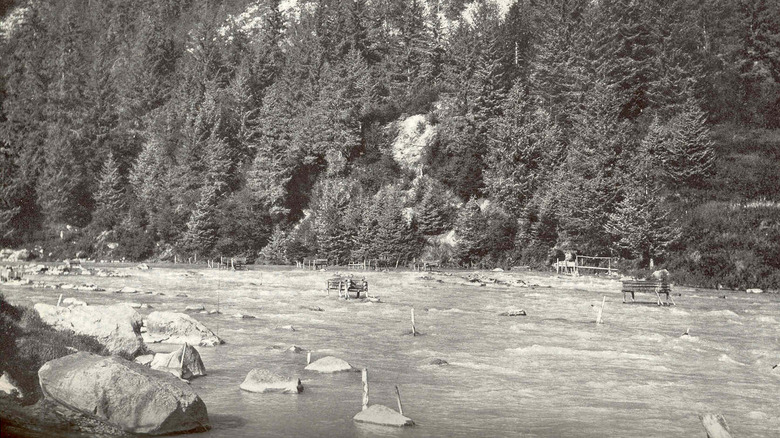

Policing Native fishing

One of the many ways in which the treaties were violated was the oppression of Indigenous fishing rights, which were supposedly guaranteed by the treaties. The Seattle Times reports that as white commercial fishing grew with industrialization, Native fishing was seen as competition. Native fishers were blamed for salmon declines, despite the fact that commercial fishing, dam building, and logging were found to be responsible for the decline in salmon. And "according to the state's own figures, Indians were catching less than 5% of the harvestable salmon in the region at the height of the fish wars" compared to white commercial fisheries.

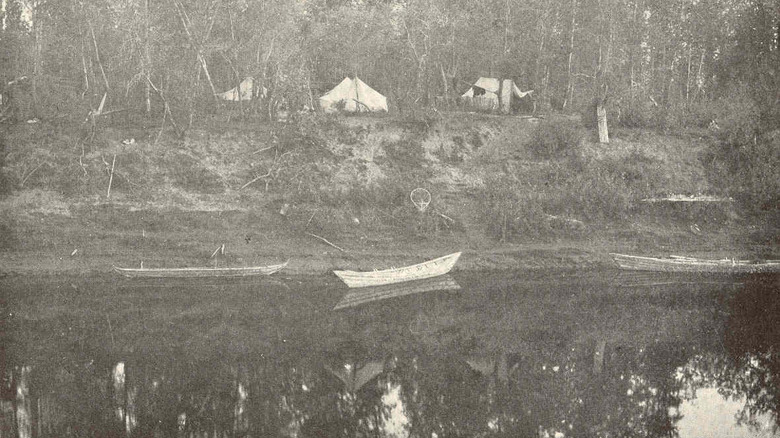

Trova Heffernan writes in "Where The Salmon Run" that in the 1960s, Washington State police officers started surveilling Native fishers "in powerboats and on foot." And within a few years, court orders were won "prohibiting Indian net fishing in the Puyallup, Nisqually, and over rivers." Sportfishermen would also fill the boats of Indigenous fishers with cement, while police would arrest Indigenous fishers and confiscate their boats and equipment, according to "Urban Cascadia and the Pursuit of Environmental Justice," edited by Corina McKendry and Nik Janos.

Joe McCoy, a Swinomish fisher, was charged with illegal fishing in 1960 and the Washington State Supreme Court ruled three years later that the state was authorized to regulate Native fishing, "provided its intent was to conserve fish runs." Washington congressman Thor Tollefson reportedly stated that "The treaty must be broken. That's what happens when progress pushes forward."

Who was Billy Frank Jr.?

Born on March 9, 1931, Billy Frank Jr. was a member of the Nisqually tribe. He was just 14 years old the first time he was arrested in 1945, but it wouldn't be his last arrest. Frank would end up being arrested over 50 times over the years for asserting his Indigenous right to fish. In 1952, Frank joined the Marine Corps for two years and resumed fishing after returning to his family's land. There, Frank continued to face attacks by the police for fishing, because the state of Washington "insisted that its authority to regulate fish and game was the controlling law," writes History Link.

Indian Country Today reports that Frank became involved in the fight for Indigenous fishing rights to be upheld and provided support to "many Indian fishing families who suffered injury and harassment on the path to taking their treaty to court." Frank's land became known as Frank's Landing, and it was "where the first Indian lance of protest activism was stuck in the ground in the early 1960s."

During the Fish Wars, Frank was repeatedly attacked by the state and arrested for fishing. The Seattle Times writes that on one occasion, a state boat rammed into Frank's canoe, a prized possession that had been carved by Frank's friend Johnny Bob. Frank fell into the water and almost drowned. Meanwhile, the state confiscated his canoe.

Fish-ins

As a protest against the oppression of Indigenous fishing rights, many Native people staged "fish-ins." Starting in March 1964, "fish-ins" reportedly originated among the Makah elders, according to "The State of Native America," who made an appeal to 50 Indigenous nations to participate in the fish-ins, which involved fishing at times and places that were considered illegal "but guaranteed under provision of the treaties." One of the first protests was planned for March 2. The Seattle Times reports that Mary McCloud, president of the Survival of the American Indian Associations, invited Native people to join "at our usual and accustomed fishing grounds" at Frank's Landing.

There were fish-ins on numerous rivers during the first protests and more than 1,000 Native people from dozens of nations came from across the country to participate and show their support during the fish-ins. The National Indian Youth Council, founded in 1961 and considered to be a precursor to the American Indian Movement, also offered its support and many of its members were active in the Fish Wars.

The Yakima people didn't initially join in on the protests, but according to "The State of Native America," after state fish and game personnel arrested a group of elderly Yakima who were fishing, young Yakima men started patrolling the river with rifles to protect the fishers. "There were guns along the rivers for the first time since the Yakima Wars."

Violence during the protests

The state of Washington responded by sending police to arrest Native fishers "using tear gas, blackjacks, and excessive violence." Many people were reportedly hospitalized due to police attacks during the Fish Wars. Escalating the conflict "with a military-style campaign," state officials used tear gas and billy clubs and guns with impunity against the protestors, regardless if they were adults or children. The arrests and raids on fishing camps like Frank's Landing were described as "paramilitary-style" activities.

In addition, "numerous white fishermen took their cue from such police actions and began invading individual Indian fishing camps and destroying them," according to "Pan-Tribal Activism in the Pacific Northwest" by Vera Parham. The Seattle Times reports that in 1971, Hank Adams, an Assiniboine-Sioux activist, was shot in the stomach while fishing. He survived, but the local police showed little interest in finding his would-be murderer and they dropped the case. Although the FBI did an investigation, Adams's "assailants were never caught."

The State of Native America writes that the idea policy of armed self-defense in the fishing rights movement was pushed by an elder Nisqually woman. The Survival of the American Indian Society (SAIA), which was also part of the Fish Wars, were also not pacifists and, according to The Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, "had frequently threatened to defend themselves with violence if necessary."

The federal government sues

On September 9, 1970, police raided a Native fishing camp under the Puyallup River Bridge. In addition to tear-gassing the protesting fishers, police destroyed the camp and arrested almost 60 people. Among those who got gassed, according to Last Real Indians, was U.S. Attorney Stan Pitkin.

After witnessing the brutal behavior of state officials, Pitkin "took the first steps to file U.S. v. Washington on behalf of the tribes." Acting as a trustee for 14 treaty tribes, the federal government sued the state of Washington for infringing on the treaty rights of Indigenous people in Washington.

The Seattle Times writes that U.S. District Court Judge George Hugo Boldt was assigned to the case and ironically, he'd crossed paths with the fish-ins before. Six years earlier, Frank and five friends spent a month in jail for a fish-in and while their attorney had tried to get them released on the grounds of illegal arrest, their release was denied. "One of the judges who denied their release was George Boldt."

The Boldt Decision

The biggest question in the lawsuit was whether or not the state of Washington was legally allowed to regulate the fishing practices of Native people who had signed treaties with the federal government. The Seattle Times reports that while both Native people and the state were using the treaty clause "The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the territory" to justify their actions, there was a difference in interpretation. The state considered "in common with all citizens" to mean that Native people were subject to the same amount of state control as non-Native people. Meanwhile, Native people argued that "usual and accustomed places" meant that their fishing wasn't to be restricted.

In 1974, Judge Boldt ruled that not only did "in common with" meant that Native people were entitled to "half the harvestable salmon running through their traditional waters," using an 1828 edition of the Webster's Dictionary, but he also made Native tribes "co-managers of the state's fisheries." Last Real Indians writes that this ruling was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1979.

After giving his verdict, Judge Boldt ended up becoming the subject of abuse and was targeted by "state and local officials, the ICERR, local and national 'sporting' organizations, the commercial fishing industry, the John Birch Society, and the Ku Klux Klan," according to "The State of Native America."

Legacy of the Fish Wars

It took some time for the Boldt Decision to have an effect. According to The Olympian, most non-Native fishers ignored the decision and the state refused to enforce it, convinced that the ruling would soon be overturned by the Supreme Court. It was only once the ruling was upheld that it began to have any impact.

However, Cultural Survival notes that "rather than returning fish to traditional Indian river and inshore fisheries, the Boldt Decision appears to be encouraging the creation of a wealthy class of offshore, capital-intensive, treaty-tribe fishermen who are intercepting much of the resource before it reaches the traditional estuary and river fisheries of the tribes." In addition, when it came to fish like salmon, the 50/50 ruling was "largely meaningless" because of how much the salmon fishery in Puget Sound was destroyed by logging and development. Indian Country Today notes that after the battles of the Fish Wars, the battles continue towards "reversing more than a century of bad environmental policy so salmon populations can rebound and thrive."

The biggest impact of the ruling was the president it set for the notion of tribal sovereignty as well "the legal status it gave the treaties." Notably, the ruling can also be read as establishing the state's obligation to protect fish habitats, "to ensure the tribes' rights to fish in perpetuity."