Black Land Loss In The United States Explained

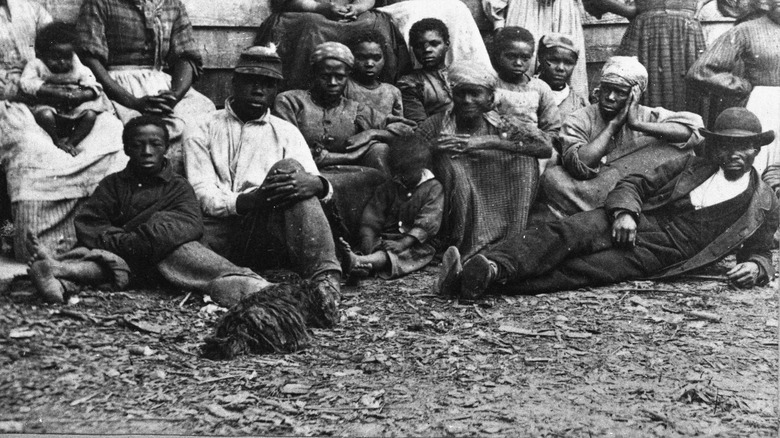

When white settlers colonized the continent of North America, they knew how important land was because they did everything in their power to dispossess Indigenous people from their land. It's estimated that Indigenous people across the United States have lost almost 99% of their historical lands, and as this land was taken and redistributed, ownership of the land was intertwined with the idea of freedom.

This is why after the Civil War, land ownership was seen by many formerly enslaved people as a way to freedom and independence. But although there were some gains made in the aftermath of the Civil War, the story of Black land ownership in the United States is largely a story of loss, overrun by discrimination, manipulation, and violence by white Americans.

There are dozens of contributors to the dispossession of land owned by Black people in the United States, including heirs property laws, racist farm loan lending practices, and redlining. And ultimately, the total loss amounts to billions in lost generational wealth. As lawyer Nathan Rosenberg puts it, "If you want to understand wealth and inequality in this country, you have to understand Black land loss." This is Black land loss in the United States explained.

Before the Civil War

Before the emancipation of enslaved Black people in the United States, the number of free Black people amounted to roughly half a million. And according to agricultural history, some free Black men were able to acquire land. Although their "holdings were usually very small and their farming mostly at subsistence levels" and they represented only a small fraction of the free Black population, Black landowners were recorded in the United States census as early as 1790.

USA Today reports that there were dozens of free Black farm communities in the Midwest during the antebellum period, including Lyles Station in Indiana, though at the time white settlers referred to the area as the "Northwest Territory."

According to Louisiana History, free Black people in Louisiana before the Civil War were "by far, the most prosperous group of African descent in the United States, controlling substantially more property" than free Black people in other states.

'Forty acres and a mule'

As the American Civil War was coming to an end, General William T. Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton met with a group of 20 Black ministers and community leaders in Savannah, Georgia on January 12, 1865. PBS writes that Garrison Frazier was the "chosen leader and spokesman" for the Black community, and he informed Sherman and Stanton that "the way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor." Four days after this meeting, Sherman issued Special Field Order 15, which reserved land in Georgia and South Carolina for formerly enslaved people to settle. Because the order noted that "each family shall have a plot of not more than forty acres of tillable ground," Special Field Order became known as "40 acres and a mule."

In total, roughly 400,000 acres of land were redistributed to 40,000 formerly enslaved people as the Freedmen's Bureau was also briefly authorized to redistribute confiscated land. However, as Vaughnette Goode-Walker notes, this became "one of the biggest 'gotchas' in American history," per NPR.

The redistribution lasted less than a year as President Andrew Johnson restored the majority of the land to its white formerly-Confederate owners, despite the fact that Black freedpeople had settled most of the land. As a result of the dispossession, only around 2,000 Black Americans were able to hold onto the land they were given after the Civil War.

The Southern Homestead Act

On June 21, 1866, the United States signed the Southern Homestead Act into law. The first Homestead Act had been signed into law during the Civil War on May 20th, 1862, which meant that formerly enslaved Black Americans were unable to take advantage of the land distribution. As a result, the Southern Homestead Act was passed and in the first six months, Aeon writes that "unoccupied southern land was offered exclusively to African Americans and loyal whites." But after 1867, landless former white Confederates were also applying to the Southern Homestead Act for land.

This redistribution has been described as "the most extensive, radical, redistributive governmental policy in US history" and in 2000, it was estimated that roughly 25% of the US adult population was descended from original Homestead Act recipients.

Federal land in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi was redistributed, but the percentage that went to Black Americans is vanishingly small. Over 1.6 million white families became landowners due to the two Homestead Acts, while "only 4,000 to 5,500 African-American claimants ever received final land patents from the [Southern Homestead Act]." Even when land patents were granted, the land was often of poor quality. And as Zinn Education Project notes, "it is important to include how the land was stolen" from the Indigenous people of the North American continent repeatedly, because none of the land redistribution that occurred would have been possible without stealing the land in the first place.

Rise in land ownership

Despite the inefficacy of the Southern Homestead Act, Black land ownership continued to rise through the end of the 19th century, although this varied across southern states. According to agricultural history, in counties of the "Cotton South," which included the states from South Carolina to Texas, initially less than 10% of the cultivated land was owned and worked by Black people. But in the "Upper South," white people were less resistant to the idea of selling land to Black people and Thomas C. Walker reportedly stated that "if a colored man has got money and wants land he can get it." By 1890, the proportion of Black farm owners in states like Kentucky and Virginia "had risen above 40%."

By the end of the 19th century, the number of Black landowners had increased even in the Cotton States. In Texas alone, the number of Black farmers who owned their own land jumped from around 800 to over 12,500, Kyle G. Wilkison writes in "Yeomen, Sharecroppers, and Socialists."

Black Perspectives also notes that Black women were also able to acquire land through an "internal land trade," whether by mutual aid, when "landed kin helped landless family members acquire land," or through saving up and purchasing land.

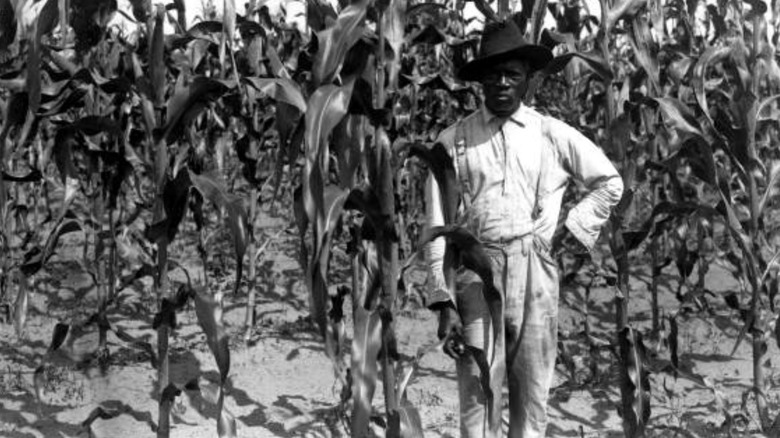

14% of farm owners

1910 to 1920 are considered to be the peak years for Black landowners in the United States. Making up 14% of all farm owner-operators, Eater writes that formerly enslaved Black Americans and their descendants accumulated between 13 to 19 million acres of land. This number peaked in 1920 with over 922,000 non-white-owned farms. Among Black farmers in the Upper South, around 44% owned their own land by the 1920s. In the Lower South, "as a whole it remained under 20% in 1920."

According to agricultural history, this increase in farm ownership was in part due to "the movement of whites off the land to take jobs in industry, jobs which were not available to blacks, [as well as the] readiness of white bankers to extend farm loans to rural blacks." As a result, Black farm owners were not only able to acquire land, but they were also able to increase their acreage by up to 33% between 1900 and 1910, "compared to 7% for whites."

However, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) notes, this increase in land ownership by Black Americans wasn't a majority experience. Most Black farmers were tenant farmers and sharecroppers and "enactment of Jim Crow laws in the late 1890s empowered landlords and planters to try to extract more output from tenants and sharecroppers with less compensation."

Blackdom, Deerfield, and DeWitty

The rise of Black land ownership in the United States led to the creation of dozens of Black-owned homestead colonies in the Great Plains such as Blackdom, Nicodemus, Dearfield, and DeWitty. According to The Washington Post, up to 200 people lived in colonies like Blackdom and Dewitty, while "Dearfield was home to more than 200 homesteaders."

Founded in the 1870s, Nicodemus in Kansas is the oldest Black-owned colony west of the Mississippi. At its peak, Nicodemus had over 700 migrants, but the National Park Service writes that the population stabilized around 300 by the 20th century. And The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reports that with 22 residents as of 2021, "Nicodemus is the only Black homestead colony that is still inhabited."

Some of the colonies, like DeWitty and Blackdom, had their own schools and post offices and thrived for years until droughts and the Great Depression caused the communities to "rapidly depopulat[e]."

Heirs' properties

Although Black people in America were able to acquire land up through the beginning of the 20th century, holding onto the land was another story. "81% of early Black landowners" didn't leave a will, either due to a lack of legal resources or distrust of the American legal system. ProPublica reports that as a result, the land would become an heirs' property, "a form of ownership in which descendants inherit an interest, like holding stock in a company," when the landowner died. Sometimes, there can be up to 100 known heirs who are all "legally co-owners."

The USDA has described heirs' properties as "the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss." Not having a will ends up jeopardizing land ownership, and many "are vulnerable to laws and loopholes that allow speculators and developers to acquire their property" without the full consent of the family

The Guardian reports that in some cases, the land is passed down informally, but the partial interest in the house is continually split among new descendants. However, none of the descendants with partial interest hold the actual title to the house, and as a result, are "excluded from many federal and state grants historically given to homeowners to recover from disasters." This was seen after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when "up to $165 million of recovery funds were never claimed because of title issues."

It's estimated that heirs' property makes up between 33% to 60% of Black-owned land in the south.

Torrens Acts

Another major factor in Black land dispossession was the Torrens Act. Land broker Theodore Barnes describes the Torrens Act as "a legal way to steal land." According to Modern Farmer, although states introduced the Torrens Act as a way to simplify title registries, they were used by "third parties to force families off their land through partition sales." Essentially, the Torrens Act allowed a court-appointed lawyer to grant adverse possession "without a traditional judicial proceeding" and with minimal proof required, according to The Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy. This made it even easier for Black land to be dispossessed because once one owner sells a portion of property, there are real estate laws that help non-hereditary owners to buy "the entire property, often at below market rates."

This practice is known as a partition sale and some people wouldn't even know about the partition sale until they were "served an eviction notice." This is essentially what happened to the Reels family, who didn't even realize they'd lost their land and missed the deadline to appeal the Torrens decision, writes Equal Justice Initiative. When brothers Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels refused to vacate the land, they were jailed by a North Carolina court for civil contempt. They were imprisoned for eight years, becoming "two of the longest-serving inmates for civil contempt in U.S. history."

Discriminatory loan servicing

The Farmers Home Association, which is the financial lending branch of the USDA, also played a major role in Black land dispossession. PBS reports that Black farmers were excluded from federal farm assistance programs in what's described as "a systematic pattern of discrimination." The USDA has acknowledged this pattern of discrimination. According to a USDA report from 1998, this history of discrimination is "well documented" and "has been a contributing factor in the dramatic decline of Black farmers over the last several decades."

Due to the discriminatory lending practices and loan denials, the Equal Justice Initiative writes that Black farmers were forced into foreclosure, "and their property was purchased by wealthy white landowners." And while white farmers were given checks for operating or relief loans for hundreds of thousands of dollars, The Guardian reports that Black farmers like John Boyd Jr. would be "begging for $5,000" and still be denied. Loans were denied to non-white farmers "at a rate of 10-15% times higher than white farmers, varying between states." And on the rare occasion that loans were approved, non-white applicants were found to wait "an average of three times longer to receive their money than their loan counterparts."

The Nation reports that during the worst of the farm crisis in 1984 and 1985, "the USDA lent a total of $1.3 billion to nearly 16,000 farmers to help them maintain their land. Only 209 of those farmers were Black."

Violently forced off the land

The dispossession of land from Black farmers and landowners didn't always happen through legal theft or bureaucratic discrimination. Sometimes the process was an incredibly violent ordeal. The Authentic Voice writes that land ownership often made Black people targets of violence, either because white supremacists "just wanted to drive them from their property" or because "the attackers wanted the land for themselves." One investigation by the Associated Press found at least "57 violent land takings." And Ray Winbush, the director of the Institute for Urban Research at Morgan State University, states, via ProPublica, that "most Black men were lynched between 1890 and 1920 because whites wanted their land."

Atlanta Black Star reports on one such incident from 1908, in which 50 hooded men surrounded the home of David Walker, a black farmer, "and ordered him to come out for a whipping." When Walker refused, the mob set his house on fire and shot at Walker's family as they tried to escape from the flames. No one was ever charged for the murders and "Land records show that Walker's 2 1/2-acre farm was simply folded into the property of a white neighbor" despite the fact that three of Walker's children survived the incident.

The "reign of domestic terror" also contributed to the Great Migration, and as millions of Black people relocated out of the South between 1916 and 1970, thousands of acres of land were dispossessed from Black Americans.

From 14% to less than 1%

Combined together, all of these factors led Black land ownership among farmers to drop from its height of 14% in 1920 to 1.3% in 2019. And The Guardian reports that as of 2019, Black farmers owned only "0.52% of America's farmland." For Black farmers who managed to hold onto their farms, "their average acreage is about one-quarter that of white farmers" and as a result, they make less than $40,000 annually compared to the $190,000 made by white farmers.

This decline happened drastically over the course of the 20th century. According to The Nation, compared to the 925,000 Black-owned farms in 1920, there were only 45,000 in 1975. "It was almost as if the earth was opening up and swallowing Black farmers." This number has continued to drop and was last reported to be less than 36,000 in 2021, CBS reports.

ProPublica reports that between 1910 and 1997, Black farmers lost up to 90% of their land. And it's estimated that "Black families have been stripped of hundreds of billions of dollars because of lost land."

Pigford v. Glickman

In 1997, over 400 Black farmers, including John Boyd Jr., sued the USDA, alleging that the USDA ignored their complaints and denied them loans due to rampant discrimination. The class-action, known as Pigford v. Glickman, reached a settlement of over $1 billion in 1999, and The Guardian reports that 16,000 Black farmers ended up receiving $50,000 each.

However, after the settlement deadline passed, many Black farmers came forward to say that they hadn't been aware of the settlement or the deadline. However, the compensation for those farmers wouldn't come until 2010, when President Barack Obama signed a bill "authorizing $1.25bn in compensation to the late claimants." Unfortunately, in the time it took for this compensation to be authorized, countless older Black farmers passed away.

Although some of these discriminatory practices ended up being addressed by the turn of the century and the USDA claimed that everything changed after Pigford v. Glickman, The Counter reports that even under the Obama administration, "USDA employees foreclosed on Black farmers with outstanding discrimination complaints, many of which were never resolved." And meanwhile, the USDA used "an array of manipulated statistics" to bolster their civil rights image, despite the fact that the USDA "sent a lower share of loan dollars to Black farmers [during the Obama administration] than it had under President Bush."

Property as well as land

Although Black land loss in the United States has primarily involved farmland, a similar pattern of dispossession can also be seen with property. The Atlanta Black Star reports that the subprime mortgage crisis "preyed upon Black and Latino homeowners through institutional racism and discriminatory lending" and resulted in a similarly substantial loss of wealth among Black and non-white people in America. Between 2007 and 2010, "Black families lost 31% of their wealth."

The Conversation also notes that in 2017, the racial homeownership gap was "at its highest level for 50 years," with less than 42% of Black Americans owning a home compared to almost 80% of white Americans. And while both of these numbers represented a decline since 2010, Urban Institute reports that white homeownership "represented a 0.7 percentage point decline" and black homeownership "represented a 2.7 percentage point decline."

Prosperity Now also found that between 1983 and 2013, median Black household wealth has also decreased by 75% while median white household wealth has increased by 14%.