The Untold Truth Of The Channel Tunnel

The English Channel is one of the best-known and most important waterways in the world. Britannica notes that the narrow strip of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Britain from continental Europe has acted as a pathway for trade, a military barrier, and one of the most famous borders on the globe. It is arguably what made Britain, Britain.

The English Channel, however, is not eternal. In fact, according to the U.K.'s Natural History Museum, since at least 950,000 years ago Britain has been intermittently connected with the mainland based on the vicissitudes of the ice ages. The more ice, the lower the sea, at which times the English Channel became a broad land bridge. The last time the two lands were connected was reported by the BBC to be about 6,100 years ago, during the Mesolithic period. At that time, the English Channel was flooded and assumed the shape that we are familiar with today.

The English Channel has severed Britain from Europe so that travel between the two usually had to be done by watercraft. This changed in the late 20th century, when one of the most remarkable engineering works in history was created: the Channel Tunnel, also called Eurotunnel and informally nicknamed the Chunnel. This ambitious project realized centuries of dreaming to reconnect Britain to the mainland. Yet it wasn't as simple as digging a hole and hoping for the best. Let's take a look at some of the little-known truths about the Channel Tunnel.

The first Channel Tunnel was proposed by a French engineer

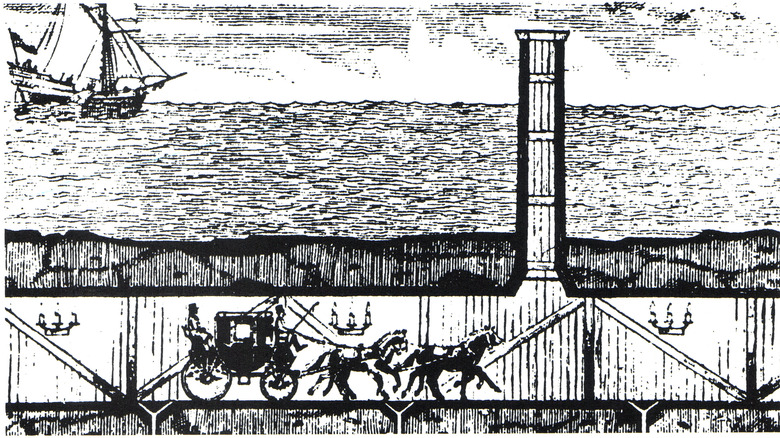

Digging a tunnel under the English Channel has only been accomplished in recent decades, but the truth is that the concept for one is over two centuries old. According to The New York Times, the first known proposal for a tunnel was not made by an Englishman, but by the French engineer Albert Mathieu in 1802. His plan included two tunnels, one of which would be dug from France and the other from England. These would have lamplit roads for horse-drawn carriages. To provide ventilation, he proposed chimneys that would rise out of the sea, which undoubtedly would be a terror to those on a ship. Mathieu's plan even included an artificial island on the Varne Bank, a shallow portion at the center of the Channel. This rest stop would allow for a change of horses while on the journey.

"The Tunnel Under the Channel" tells us that Napoleon Bonaparte, who was the First Consul of France at the time, was so impressed by the plan that he brought it to the attention of the British, where the idea was looked at favorably. Almost simultaneously, another Frenchman named de Mottray proposed a tunnel, but using submerged tubes. However, neither version of the tunnel went further once the Napoleonic Wars resumed in 1803 with the breakdown of the Treaty of Amiens.

They tried digging it in the 1880s

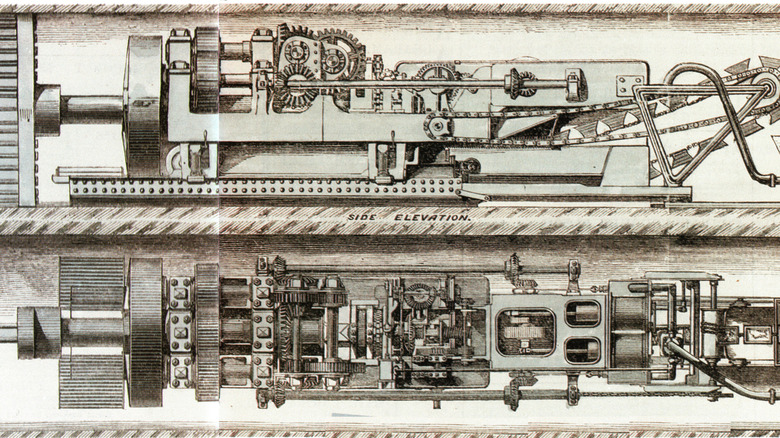

While war stopped the early concept of a Channel Tunnel in its tracks, the idea did not die away. An article in Technology and Culture explains how various proposals to link Britain to mainland Europe were floated, even going so far as the creation of an Anglo-French committee and a separate French commission, which found the idea feasible. In 1872, the Channel Tunnel Company was established in Britain, as well as the French l'Association du Chemin de Fer Sous-marin entre la France et l'Angleterre, with the idea of building it.

In 1880, work began at the base of Abbot's Cliff in Folkestone, U.K. Workers used hand tools but also, according to the BBC, a new kind of boring machine that was powered by compressed air. A second pilot tunnel was begun at Shakespeare Cliff, while on the French side, a tunnel was started at Sangatte. However, these tunnels were never linked. Political and military interests convinced the British to abandon the project for fear that it could be used for a military invasion. Also, there was a strong sense that the British wanted to maintain their separateness from the continent. While the shafts of these tunnels were backfilled, the actual tunnels still lie beneath the earth, a relic of Victorian times. It wasn't until decades after World War II that political forces aligned to make a Channel Tunnel project once again palatable.

The Channel Tunnel has trains on the left because of a compromise

The Guardian reports that Britain's Ministry of Defence softened its stance on the construction of a Channel Tunnel in 1955. By 1959, they had a plan to blow it up with nuclear weapons to prevent an invasion if needed, according to The Independent. Then in 1964, the French government officially lent its support to the idea of a tunnel. Still, it was not until the 1980s that British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and French president François Mitterrand made a concrete agreement to build the Channel Tunnel.

Thatcher wanted the tunnel to be a roadway for passenger cars since, to her, cars represented freedom and individualism. However, Mitterrand was in support of a rail tunnel, since France had much more of a rail culture than Britain. In the end, Thatcher agreed to the railway concept. It seems that the technical issue of ventilation for the exhaust from thousands of car was too challenging and expensive when compared to a rail option, which did not have the same level of pollutants.

However, Thatcher did manage to get two concessions. First, trains would run on the left-hand side. More importantly, the Channel Tunnel would not be supported with public funds. The only public investment was that the British and French rail systems both agreed they would use the tunnel. On January 20, 1986, at Lille, France, Thatcher and Mitterrand announced that Eurotunnel-Transmanche was awarded the Channel Tunnel contract.

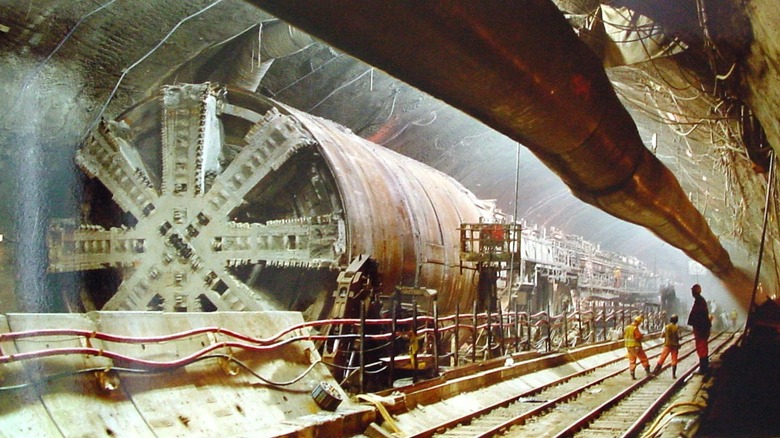

Construction of the Channel Tunnel was beset by challenges

The Constructor tells us that when work began in 1987, the engineers chose to lay the tunnel across the Dover Strait. This meant digging through a seabed composed of chalk rock and clay. To do this, engineers used 11 immense tunnel boring machines to dig out three separate tunnels. These machines have rotary heads that cut into the rock, which is then removed to the surface using conveyor belts. Using these machines is less cost-effective than other methods, but the added expense is offset by speed: the machines are much faster than traditional tunnel-digging methods. These separate tunnels were connected with cross tunnels which followed a method of tunneling known as the New Austrian Tunneling Method, an approach to tunneling which focuses on using the surrounding rock as the primary support for the tunnel.

Digging from the British side proved to be particularly challenging since there was only limited room for the concrete mixers that fabricated the segments needed to line the tunnel. Meanwhile, large terminal stations had to be constructed on both ends of the tunnel. Most of the major tunneling was complete by 1991, but according to The Guardian, residual work continued for three more years until the tunnel was officially opened on May 6, 1994. Some of the first voyagers through the tunnel included Queen Elizabeth II in a Rolls-Royce Phantom VI, accompanied by French president François Mitterrand.

The Channel Tunnel was way over budget

The Channel Tunnel was a feat of engineering, so naturally it was very expensive. An article published in the Journal of Mega Infrastructure & Sustainable Development reports that the original projected cost of the project was £4.55 billion (in 2020 currency). However, when completed, the budget had ballooned to over £10.116 billion (also in 2020 currency). The French periodical Revue d'histoire des chemins de fer, or Railroad History Review, reports that much of the cost differential had to do with escalating construction costs and unbudgeted charges on financing interest. The Journal of Mega Infrastructure & Sustainable Development commented that the tunnel could be looked at as either a colossal engineering feat or one of the greatest "white elephants" in history. Even during construction, safety concerns over fire risks led to further design changes and pushed up costs. In addition, the project was behind schedule, which further escalated its cost. It was also a one-shot, unique project, thus making true estimates hard to project. Still, the journal contends that this is not unusual for large infrastructure projects and, in fact, the Channel Tunnel compares "very favourably" with other huge transportation undertakings.

You can take your car into the Channel Tunnel -- you just can't drive it

While the Channel Tunnel was built for trains, you can still take your car into it. The trick is that the car has to be loaded onto a shuttle rail, which then speeds you under the Channel. RAC provides a step-by-step guide on how a traveler would experience the Channel Tunnel. One can travel purely as a rail passenger or take their car, in which case you can either stay in your vehicle or wander around the train. Yet in truth the experience is similar to going to an airport. Travelers should arrive early and plan to wait in a terminal until their scheduled shuttle leaves — there is even a duty free shop there. So while you may need to wait, the crossing time from Dover, U.K., to Calais, France, is just 35 minutes, which is considerably faster than the 90-minute ferry trip.

It's the longest undersea tunnel in the world

The metrics of the Channel Tunnel make this mega project, mega indeed. At its deepest, Eurostar says it is 246 feet below sea level. The BBC reports that at 31 miles, it is the longest undersea tunnel in the world, and History.com names it the third-longest rail tunnel in the world, with only Japan's Seikan Tunnel and Switzerland's Gotthard base tunnel edging it out. It is also well-used. Statista tells us that the Channel Tunnel regularly sees over a million metric tons of freight passing through it every year, as well as more than 20 million passengers in non-pandemic times. Those passengers take shuttles that leave up to four times per hour and can haul 12 coaches and up to 120 cars. Each shuttle, which is a half-mile long, can reach almost 87 miles per hour. Thanks to the Channel Tunnel, the trip from London to Paris or vice versa takes 2 hours and 16 minutes on one of Eurostar's high-speed trains.

A nature reserve was created by Channel Tunnel diggings

While massive engineering projects seem like they would be damaging to the environment, the truth is that the creation of the Channel Tunnel led to new green space. At the base of Shakespeare Cliff there is now a nature preserve that owes its existence to the tunneling. It is called Samphire Hoe, a name inspired by a line in "King Lear."

When plans were being made as to what to do with spoil that was being unearthed by the tunnel boring machines, it was decided the material would be best used for a land reclamation project at the base of Shakespeare Cliff. A barrier more than a mile long created an artificial lagoon, and over the course of the project, more than 176 million cubic feet of spoil (mainly chalk marl) was deposited within it, being relayed almost continuously during the tunneling phase. When digging was done, landscaping created a rolling seaside preserve that also included wetlands. When finished, there were 111 acres of new land. A quarter of it went to house a cooling plant for the Channel Tunnel, while the rest was set aside for Samphire Hoe, which opened in 1997. The site has proven picturesque and popular, with more than 100,000 people visiting each year to see hundreds of species of plants, birds, and butterflies.

The Channel Tunnel has a secret tunnel

We have previously emphasized how you cannot drive an automobile through the Channel Tunnel. Yet the truth is, there is an exception in the form of its little-known service tunnel. Drivers from Top Gear managed to finagle permission from Eurotunnel to drive through it. To access it from the surface at Folkestone, they drove down a nondescript side road where they dead-ended at a set of yellow steel doors that hissed open to admit them. The service tunnel is narrow — sort of like driving at the bottom of a 16-foot-diameter sewer pipe. As such, the Top Gear drivers couldn't put pedal to the metal as they ran their Ampera through on electric mode.

One of the service tunnel's primary purposes is safety. In the event a train derails or if there is a fire, people can be evacuated through cross tunnels into the service tunnel. The National Academies Press notes that air is pressurized in the tunnel, which allows for the control of ventilation and smoke. The cross tunnels are sealed but can be opened in an emergency. Emergencies do occur. For example, a 2008 tunnel fire is reported by The Guardian to be one of the worst in the service's history. This blaze started when a truck on the shuttle caught fire. It took 16 hours to control. Fortunately, there were no deaths. The truth is that the Channel Tunnel has a strong safety record.

The Channel Tunnel leaks

When digging the Channel Tunnel, engineers looked for the most favorable type of rock to dig through. To this end, the London Geological Society says they chose to bore through layers of marly chalk, which is less permeable than other rock strata. To further keep seawater out of the tunnels, Engineering Science Magazine reports that the tunnel is lined with 5-foot-thick concrete walls. All told, the amount of concrete used in the Channel Tunnel could build 100 buildings.

Yet despite all this engineering, the truth is that the Channel Tunnel leaks, and that is just fine. Even Eurotunnel admits it, but emphasizes that the tunnel is, in fact, designed to leak. A combination of groundwater and seawater enters the Channel Tunnel continuously and is promptly dealt with using massive pumps. Why was it designed to leak? The Baltimore Sun explains that it helps to dissipate outside pressure from building up.

The Channel Tunnel is a hotspot for the migrant crisis

The Channel Tunnel represents a major conduit between nations. As noted earlier, Statista shows that over 20 million people use it annually. However, not all travelers through the Chunnel are authorized to be there. The truth is that the Channel Tunnel has been targeted as a major artery for illegal immigration. Criminal gangs have organized illegal trafficking of migrants who have been desperate to seek a new life, usually from France to Britain. This problem came to a head in July 2015, when the BBC reported that 2,000 migrants attempted to pass through the Chunnel to Britain. Most of these migrants had come from camps located in Calais and sought to migrate to the United Kingdom, where they thought they would have a better life. Deaths have resulted as the human cargo is smuggled in horrid conditions. The New York Times reported that in 2015, a 40-year-old Sudanese man even walked through the Channel Tunnel, risking death from being sucked under trains. He was eventually granted asylum in Britain.

While security measures at the Channel Tunnel were stepped up, the crisis continues. The BBC regularly reports on the migrant population in Calais, who are waiting to cross the English Channel by boat or by tunnel.

The Channel Tunnel is a drug tunnel

It may be safely assumed that the vast majority of people use the Chunnel for legal purposes, but there are some who have capitalized on the quick connection to smuggle illegal drugs. InSight Crime reports that cocaine and heroin seem to be the main drugs being brought through the Channel Tunnel. One of the largest drug busts occurred in June 2022, when Metro reported that authorities seized over 440 pounds of heroin and cocaine worth more than $20 million at the French side of the Channel Tunnel.

InSight Crime offered a telling truth in its report. While the June bust was one of the largest in Channel Tunnel history, the likelihood is that the flow of drugs is steady, and this is but a sampling of it. In an interview, University of Essex criminology professor Anna Sergi stated, "When large quantities of cocaine are discovered in lorries in southern areas of the U.K., there is a good chance they have passed through the tunnel."

Is the Channel Tunnel a financial failure?

While the Channel Tunnel was a great civic work, the question of its long-term financial success is debatable. In the first decade of its history, The New York Times reports that Eurotunnel had been burdened by debt that resulted in a financial restructuring in 2007. A 2018 financial analysis of the Channel Tunnel, entitled "The Channel Tunnel Cost Benefit Analysis after 20 years of operations," notes that an investor from the beginning of the project would have seen a -0.22% rate of return. While this sounds awful, the truth is that the Channel Tunnel's situation has recovered since its initial cost overruns. An analysis by transportation consultancy ALG contended that since 2009, Eurotunnel has seen enough profit to pay out dividends to its shareholders. But for those who had been with the Chunnel from the beginning, it wasn't a smart investment. This may have been exacerbated by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, in which ridership dropped. According to Forbes, the company was almost bankrupt after lockdowns and travel restrictions and needed to receive a €290 million bailout to stay afloat.