Dr. Seuss First Got Published Because Of A Chance Meeting

In the 1930s, Theodor Seuss Geisel was an illustrator for Life, Vanity Fair, and other publications, while quietly working on his first children's book (via Britannica). In just a few years, his world would change dramatically. He would become a published author. When World War II broke out, Geisel became an editorial cartoonist, then joined the army and helped create documentaries about the conflict. A few of the films he wrote won Academy Awards. Upon returning to normal life in the late 1940s, Geisel, as Dr. Seuss, refocused on children's books and over the next four decades produced masterpiece after masterpiece.

There was the story of an elephant and nearly microscopic villagers in "Horton Hears a Who!" in 1954. Three years later, a tall feline destroyed — and then cleaned — the home of two bored children in "The Cat in the Hat," while a green miser plotted to steal hundreds of presents from under trees in "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" "Green Eggs and Ham" taught readers to try new foods (and experiences) before judging them. Later in his career, Dr. Seuss spoke for the trees in "The Lorax" and marveled at all life's possible adventures in "Oh, the Places You'll Go!"

His books have inspired and been adored by millions of children and adults alike. But they nearly didn't happen, which is a remarkable story in itself.

And to think that it happened on Madison Avenue

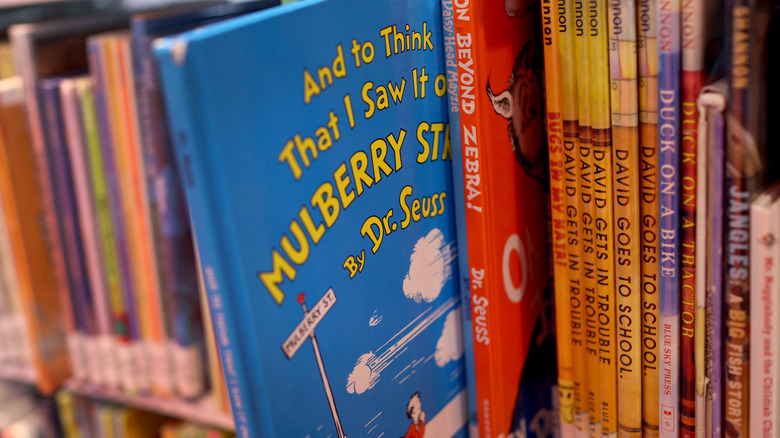

Remember that first book Dr. Seuss was working on? No one wanted it. "And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street" was a story about a boy walking home from school. His imagination runs wild. There appear zebras, elephants, and giraffes. An entire parade marches down the street with him, with an airplane dropping confetti and magicians doing tricks. When the child gets home, he's too embarrassed to tell his father his imaginings, and admits all he saw on Mulberry Street was a one-horse wagon.

Geisel's book had been rejected by 27 publishers, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The manuscript in his hands, he trudged sadly along Madison Avenue in New York City. There he ran into Mike McClintock, a friend from Dartmouth College from over a decade ago. Geisel explained what he was up to, and McClintock dropped a bombshell: He was a children's editor at Vanguard Press! He took Geisel to his office, and Vanguard immediately bought the book. The career of Dr. Seuss was launched, and he found more than one way to thank McClintock for it.

Dr. Seuss Returns the Favor

Dr. Seuss dedicated "And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street" to Mike McClintock's wife, Helene (via Dartmouth College). He also renamed the boy in the story Marco, after their son. "You picked me off Madison Ave. with a manuscript that I was about to burn in my incinerator, because nobody would buy it," Geisel wrote to his friend in the late 1950s, when a Grinch and a cat had made Dr. Seuss famous (via Smithsonian Magazine). "And you not only told me how to put 'Mulberry Street' together properly ... but after you'd sweated this out with me, giving me the best and only good information I have ever had on the construction of a book for this mysterious market, you even took the stuff on the road and sold it."

The experience taught the author something about success, failure, and fortune. Geisel/Seuss explained elsewhere, "That's one of the reasons I believe in luck. If I'd been going down the other side of Madison Avenue, I would be in the dry-cleaning business today!" (via The Guardian). The year 1958 saw the publication of McClintock's own children's book, "A Fly Went By." It was published by Beginner Books, a Random House imprint co-founded by Dr. Seuss.

In 2021, Geisel's estate announced that "Mulberry Street" was one of six of his titles that would no longer be published because of "offensive imagery," including hurtful racial stereotypes, as The New York Times reported. Dr. Seuss Enterprises made the decision after consultation with educators and other experts in the field, according to another New York Times report.