Meet Xin Zhui: The Most Well-Preserved Mummified Body In History

In 1971, workers near Changsha, China were digging an air raid shelter when they made an astonishing discovery. Deep inside a hill were three tombs from the Han Dynasty; that of the Marquis of Dai, his son, and his wife, Xin Zhui, otherwise known as Lady Dai. As Discover Magazine explains, the Marquis and his son were of little interest to researchers as their bodies were not well preserved. Lady Dai, however, was a different story. Although she died in 163 B.E. or over 2,000 years ago, her remains appeared to be life-like.

Zhui had hair on her head, eyebrows, and eyelashes. In addition, her skin was soft and her body was flexible. Even more astounding — there was still blood in her veins. It's for this reason that Zhui is believed to be the finest preserved ancient remains that have ever been unearthed. But who was Lady Dai? As the Marqui's wife and a noblewoman, Archaeology Magazine reports that Zhui lived in the lap of luxury. Her intricate tomb, which was filled with more than 1,400 items, served to reflect this. Her opulent lifestyle, however, is also believed to have killed her. As described by Julie Rauer at Asian Art, Lady Dai was "reputedly a beauty" in her youth, yet over time the opulence afforded to her as a noblewoman including myriad culinary delights and servants who enabled her to do very little led to a life of obesity. The well-preserved body even retained a double chin. Ultimately, Zhui was overweight and sedentary, which led to her death at age 50.

An autopsy was done on her mummified body

Zhui's body was so preserved that researchers were able to conduct an autopsy on her. Their findings were staggering. Zhui's organs, including her vagus nerve — which regulates involuntary systems of the body like digestion and heartbeat — were unscathed by time. It was also found that she had Type A blood and 138 undigested melon seeds in her stomach and intestines. Researchers theorized that this was likely Lady Dai's last meal. Discover Magazine writes that she was not in the best of health; she had high cholesterol, diabetes, high blood pressure, and a parasitic infection.

Charles Higham, from New Zealand's University of Otago (via Discover Magazine), explained "She overindulged, perhaps in a feast ... and then she had a heart attack and that was the end of her." Zhui also had gallstones and liver disease. Blood clots in her veins pointed to her cause of death. Discover Magazine notes that although it was customary for Chinese nobles to preserve their remains after death, it was unlikely for their efforts to prevail. Somehow, Lady Dai's body, which was found 12 meters (or over 39 feet) underground, did.

Zhui lived during the era of Han Dynasty, and according to Brittanica scientific advancements were sought after by the ruling party. However, the notable achievements of that time have more to do with practical inventions than the mastery of preserving human bodies. Yet a perfect confluence of burial rituals and ideal conditions left humanity with an unprecedented look at the life of a wealthy middle-aged woman who lived more than 2,000 years ago.

How was she preserved so well?

The conditions in Zhui's tomb were just right for her preservation. Besides its location in an area where the temperature was cool enough to stave off decomposition, it was also airtight. This created a barrier that prevented bacteria, water, oxygen, or anything else from entering her final resting place. In addition, Lady Dai's remains – including silk sachets of aromatic herbs in each hand — were placed inside four nesting coffins. The outer box was simple while the three inside were lacquered and elaborately painted with various symbols and themes encompassing death, the afterlife, and immortality. The innermost coffin was also adorned with feathers.

Her burial vault was packed with charcoal and sealed with clay and dirt. A substance that has been described as paste-like soil was also found on the floor. Zhui's body was wrapped in 20 layers of silk and found in 21 gallons of a mystery liquid. Ancient Origins states that the substance was mildly acidic and contained magnesium. It also had a red tint to it. That being said, it's unknown what role, if any, this fluid had in preserving Lady Dai's remains. Quite possibly, it could have appeared with time. Nevertheless, it's unknown how and why her body remained in a near-perfect condition for thousands of years. The technique that was used to preserve Lady Dai is a mystery; embalming liquid was not found inside her body.

Ancient artifacts were discovered in her tomb

As the Asian Art Museum explains, during the Han Dynasty, royalty was buried with everything they could possibly need in the afterlife — which were the same things that were useful on Earth. That certainly held true for Lady Dai, who the New York Post reported was nicknamed "The Diva Mummy."

Her tomb was the definition of excess. Nearly 100 dishes of food were discovered with her body, including strawberries, beef, goose, and sparrow. Archaeologists also found silk clothing, lacquer pieces, and wood carvings of her servants. Archaeology Magazine states that containers for wine and makeup were also uncovered. Additionally, there were fingerless gloves, fragrant silk sachets, musical instruments, and practical items like a "toilet box" and furniture, per Smarthistory.

Willow Weilan Hai Chang later organized an exhibit of these items at the China Institute Gallery in New York City and explained, "These objects show that Lady Dai lived a luxurious life, which she enjoyed very much," she added, "She wanted to maintain the same lifestyle in the afterlife."

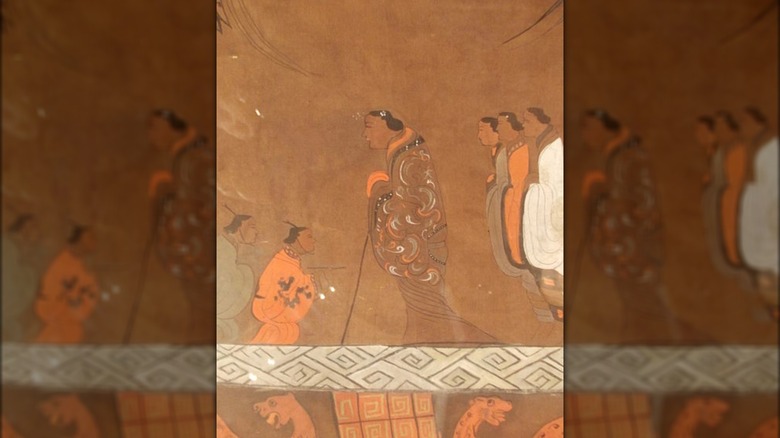

A silk banner was also found in Zhui's tomb. It represents her life after death. The banner, which is in pristine condition, is divided into four sections that illustrate heaven, Lady Dai with her servants, her body surrounded by mourners, and lastly, the underworld. This piece is intended to demonstrate that Lady Dai would enjoy a comfortable afterlife with all the items found in her tomb. Although Lady Dai had a premature death by today's standards, she is now eternally resting at the Hunan Provincial Museum in China.