What The Mummy Gets Wrong About Archaeology

What's not to love about 1999's "The Mummy"? This rip-roaring adventure features an engaging cast of stars, including Brendan Fraser's Rick O'Connell, one of the goofiest, most lovable himbos ever to grace an adventure flick. Rachel Weisz is delightful as a no-nonsense, clumsy, wannabe Egyptologist who can kick some serious butt.

From Arnold Vosloo's imposing High Priest Imhotep to Oded Fehr's Ardeth Bay and Patricia Velasquez's body-painted Anck-Su-Namun, it's hard to take your eyes off this spectacle. Gorgeous cinematography, intricate costumes, and stunning replicas of Egyptian artifacts and sites round out the adventure. And who can forget about the horror of flesh-eating scarabs and live mummification? Yikes!

An admixture of horror, comic relief, romance, and Egyptian curses, "The Mummy" makes for a mad capped ride through the not-so-realistic Hollywood version of archaeology. But how wrong is this entertaining little bit of escapism when it comes to what archaeologists do? Let's put it this way. If you're after a documentary about life as a shovel bum, this is not the film for you. There's an awful lot that "The Mummy" gets dead wrong about archaeology. So, before you grab a wide-brimmed fedora and don that full khaki outfit to go on a hunch-based dig, here's what you need to know.

Sight-reading Egyptian hieroglyphs isn't a breeze

There's always at least one character in every movie dealing with ancient Egypt who can break into full-on, real-time hieroglyph translation like it ain't no thing. (Hint: Evelyn Carnahan.) But the reality for archaeologists isn't as simple. Some scholars prove fluent in the ancient language, namely Egyptologists. But it's not a language informally thrown around by just anyone interested in archaeology or even ancient Egypt.

Archaeology comes with many distinct subdisciplines, including prehistoric and underwater archaeologists (via National Geographic). Paleopathologists study the history of disease, and historic archaeologists examine the eras after the invention of writing and record-keeping. We're just scratching the surface when it comes to niches, but you get the drift. Knowing how to read hieroglyphs isn't necessary for every archaeologist, and certainly not every librarian!

What's more, just two centuries ago, people didn't know how to read hieroglyphs at all. The first scholars began translating hieroglyphs relying on the Rosetta Stone in 1799 in France, per Discover. They did this by examining a decree written by Ptolemy V, a Hellenistic Egyptian pharaoh. Written in Greek, Demotic, and hieroglyphs, scholars were finally able to crack the code by comparing the unknown symbols with their known Greek and Demotic counterparts, according to the British Museum.

Khaki isn't the official wardrobe of an archaeologist

From Indiana Jones to Rick O'Connell, big-screen depictions of archaeologists often look fascinatingly similar. While these Hollywood versions of shovel-wielding scholars like to live large in khaki, it isn't the official wardrobe of archaeologists. That said, light neutrals aren't necessarily a bad idea depending on where fieldwork takes place. (Many archaeologists get behind the wide-brimmed hat, too.)

According to Warfare History Network, the first individuals to don khaki were members of the Imperial British military serving in India in the 1840s. Why the switch from red coats to dust-colored ones? Because traditional, scarlet, woolen outfits made little sense in a tropical climate. There was also something to be said for blending in with the environment, and a color that mirrored the local soil did the trick.

Khakis came back around during World War II as a staple of the U.S. Army (via Primer Magazine). By the next decade, they enjoyed a place in many men's closets as a go-to preppy item. The word khaki comes from Urdu and means "dust-colored."

Archaeologists aren't glorified treasure hunters

We've got to give Rick O'Connell a pass on a few things. After all, he's not an actual archaeologist like Indiana Jones. And although there's a little treasure hunting at the beginning of the film, O'Connell spends most of his time putting out the fires started by Imhotep. So, it's little wonder that a day in the life of an archaeologist looks nothing like the frenetic adventures of O'Connell or Jones (via Society for American Archaeology).

Archaeologists may be involved in a wide variety of activities during any given day. Research techniques typically used by them include archival research. (Without playing bookshelf dominoes like Evelyn Carnahan!) Checking out historical sources often proves the first step in getting to the bottom of an ancient puzzle. These sources may include everything from maps and photographs to written accounts, tax records, and more. Some archaeologists explore oral histories passed down through the generations.

The point is that an awful lot of groundwork needs laying before archaeologists dive into fieldwork, per the American Museum of Natural History. And even fieldwork is far from the drama-filled activity depicted by Hollywood. Instead of wrestling mummies and dodging booby traps, you'll find archaeologists and their crews on their knees scraping thin layers of sediment with trowels before sifting it in search of artifacts.

Destroying artifacts and archaeological sites is no bueno

An awful lot of artifacts and archaeological sites get destroyed in "The Mummy," which would leave real-life archaeologists knock-kneed and slack-jawed. According to the Society for American Archaeology, archaeology requires painstakingly slow excavation practices and constant recording and reporting using photos, sketches, and journals.

The varied tools of the trade they employ reflect this. Remember those trowels and sifters? Add to these toothbrushes, dustpans, and tape measures. Some archaeologists also get into high-tech stuff like Scanning Electron Microscopes, ground-penetrating radar, and drones to help minimize their impact at a given site by gaining as much information in advance as possible.

Archaeologists also take great care when it comes to excavating a site because, as the American Museum of Natural History points out, "When a site is excavated, it is also destroyed." They use journals and photographs to copiously document every aspect of the excavation, including location within a gridded system and alignment within given geological strata. When's the last time you saw O'Connell reflecting in a journal or sketching a cross-section of sedimentary layers to map out artifact placement?

Scarabs aren't man-eating piranhas

It's hard to get the image of flesh-devouring scarabs out of your mind after watching "The Mummy." But the reality of these gentle insects (aka dung beetles) is far more mundane, per Britannica. Instead of being the vicious piranhas of the Nile, think of them as peaceful waste managers. They spend most of their time laying eggs in dung balls, which they create by rolling mini-turd snowballs. Their lives prove a far cry from the face-devouring critters of "The Mummy."

So, why the horror riff on these shiny insects? Besides the fantastic visual they create, real-life scarabs were an unlikely, though potent, symbol in ancient Egypt. Britannica explains that these beetles were "associated with the divine manifestation of the early morning sun, Khepri, whose name was written with the scarab hieroglyph and who was believed to roll the disk of the morning sun over the eastern horizon at daybreak."

No wonder Egyptians loved rocking the form of this beetle on amulets. These jewelry pieces proved so popular that there's a whole class of Egyptian artifacts featuring scarabs of various shapes, sorts, sizes, and materials. Over time, these six-legged creatures even became identified with the heart, especially of the deceased. Priests preparing mummies often placed these embellished beauties on mummies' breasts and other areas of the body. Perhaps this sparked the idea for Imhotep's nasty punishment by "The Mummy's" creators.

Scrambled chronologies confuse Ancient Egyptian history

"The Mummy" scrambles Egyptian history like a Waffle House short-order cook. For starters, the historical figure that inspired the character of Imhotep lived in the late 2600s B.C. (via the BBC). If you're stunned to learn there was a real Imhotep, you're not alone. But before you get excited about "The Mummy" as a historically accurate film, hold your horses.

The real-life dude, although fascinating, wasn't a high priest who caroused with the pharaoh's wife and ended up dung beetle fodder. Rather, he enjoyed a true rags-to-riches story as a commoner by birth who ascended to the height of Egyptian power as the righthand man of Pharaoh Djoser. Djoser even entrusted him with the building of his stepped-pyramid tomb. Imhotep's legacy would endure as later generations of Egyptians, particularly the scribe class, venerated him for determination and wisdom. Imhotep's backstory aside, the Hollywood version is all over the place when it comes to chronology.

For example, Imhotep recognizes Jewish as the "language of slaves" and calls up the Ten Plagues from the Book of Exodus in the Bible. Sure, it makes for a great plot, but significant issues exist with this timeline. Most scholars date the Exodus story of the Jews leaving Egypt to roughly 1440 B.C., long after the real Imhotep lived, as reported by Britannica. That's a century off!

Egyptian mummies didn't have their hearts removed

Throughout the movie, Evelyn Carnahan acts as the resident Egyptologist though lacking formal training. Despite her incredible ability to translate hieroglyphs in real-time, she goofs up when it comes to describing how the process of mummification worked. Oops! What does she get wrong? Priests involved in mummification removed all organs during the process. What's the problem with this? The heart.

According to Yesterday, the mummification process began with the removal of the deceased's brains. Priests went through the nose with a long hook, pulling the gray matter out in smashed-up bits. Then, they went after other organs like the stomach, intestines, liver, and lungs. In 99% of cases, the heart remained in place. Why? Because Egyptians saw it as the center of emotions and wisdom, the veritable essence of the person. So, it stayed where it lay, ready for use by the deceased in the afterlife.

From there, mummification practitioners stuffed each cadaver with natron (a form of natural salt) before immersing the whole body in it. Placed on a slanted couch, this allowed bodily fluids to run off, and they could be captured and saved for later burial with the corpse. Of course, that's just a quick rundown of a complicated procedure. But it brings us to the next point.

Mummifying people alive wasn't a thing

One of the most horrifying concepts in "The Mummy" is the Hom Dai, live mummification while getting munched on by scarabs. Thankfully, the fate of the High Priest Imhotep has no basis in historical reality. Smithsonian reports that Egyptians thought of the afterlife as too sacred to sully with such barbaric practices.

Something like the Hom Dai also defeated the purpose of mummification. The BBC explains that Egyptians "hoped to be reanimated after death and do all the things they could do while alive — breathe, speak, eat, and move." They also that believed punishment got meted out in the afterlife by the gods, so they didn't need to dirty their hands. That's not to say mishaps didn't happen, though. Due to a lack of medical knowledge and technology, we have to assume a small percentage of unlucky living people got mummified. After all, premature burial has happened often enough to make taphophobia (fear of live interment) a significant concern.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Victorians feared being buried alive so much that they constructed "safety coffins" with bells permitting the deceased to ring for help. There's also the 1937 case of 19-year-old Angelo Hays. After a catastrophic motorcycle accident with a brick wall, he spent five days in the grave (via Mental Floss). Fortunately, an exhumation for insurance purposes found him alive and comatose. He soon recovered. Had he lived in ancient Egypt, all bets would have been off about the time the brain removal started.

The Book of the Dead didn't bring people back to life

Ready to remove another linchpin from "The Mummy's" plot? Let's talk "The Book of the Dead." Remember that document that brings the deceased back to life in the earthly realm? It's a far cry from the historical reality. This collection of writings wasn't even known as "The Book of the Dead" (via World History). The ancient Egyptians referred to it as "The Book of Coming Forth by Day or Spells for Going Forth by Day."

Far from a sexy title, it sounds more like a Wiccan self-help book. Some scholars say a better title would be "The Book of Life." But does that really have the same clickbait quality as "The Book of the Dead"? Not so much. The book contained spells and formulas meant to help the deceased navigate their way into the afterlife. It also reassured the Egyptian people that they could survive bodily death. But it never claimed to reanimate anyone.

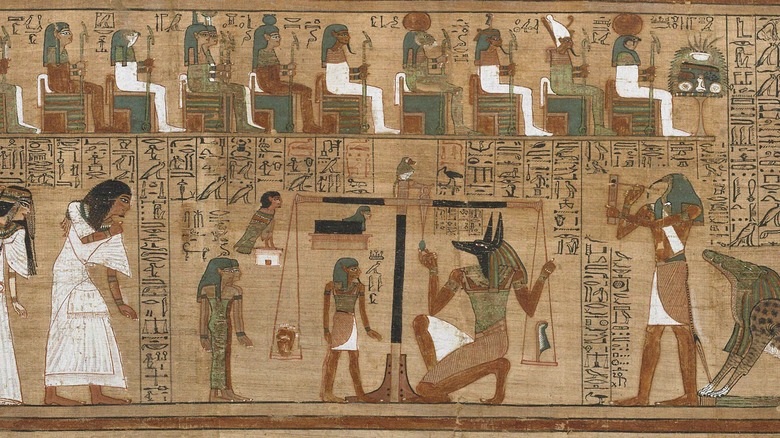

That's a far cry from the supernatural book that Evelyn Carnahan and Rick O'Connell unlock in the movie. What's more, "The Book of the Dead" wasn't a canonized text in the way we think of books today. Kellie Warren of the American Research Center in Egypt explains, "Different tombs featured distinct iterations of the 'Book of the Dead,' but certain images — like the gods weighing the deceased person's heart against a feather — recurred regularly" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Books weren't page-turners in ancient Egypt

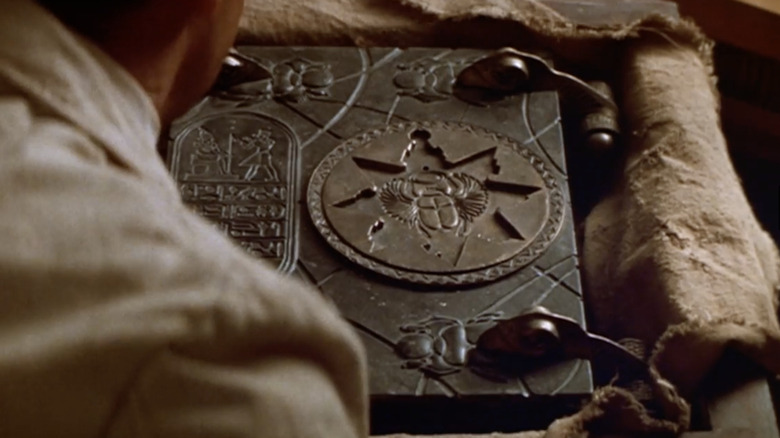

But our dissection of "The Book of the Dead" doesn't end there. Codex-style books — you know, the kinds with covers, binding, and pages — didn't exist in ancient Egypt, per Lumen Learning. So, it would have been impossible for the "Book of the Dead" to look like a contemporary tome. Egyptians developed their first written script around 3000 B.C., and they wrote on a wide variety of surfaces. These included everything from leather to stone, clay to bone. But when it came to literature and record keeping, they preferred papyrus scrolls and reed writing implements (via iBook Binding).

They made papyrus scrolls by sewing or gluing pieces of papyrus together to create a standard scroll size of 30 feet long and 7 to 10 inches wide (per Lumen Learning). That said, some scrolls proved longer than others. The longest one found so far measures a whopping 133 feet long! In other words, Rick O'Connell and Evelyn Carnahan should have been scoping out space to unroll scrolls rather than thumbing through the pages of books.

Egyptians didn't walk around solely in body paint

Anck-Su-Namun, the mistress of Seti I, is pictured essentially naked in "The Mummy," wearing body paint that mustn't be smeared. That way, Pharaoh ensures no man touches her. (We all know how well that turns out.) Although Egyptians invented cosmetics to enhance their eyes, cheeks, and lips, they didn't clad themselves entirely in body paint a la pregnant Demi Moore (via CNN). As reported by the Canadian Museum of History, ancient Egyptian women wore the equivalent of wraparound maxi dresses accentuated with bracelets, necklaces, and makeup. They also may have worn bead-net dresses that left little to the imagination, according to Realm of History.

The Natural History Museum of Utah reports that we've gained a lot of knowledge from the anicent Egyptians regarding beauty preparations: hydrating face masks, exfoliations, and even a mixture of sugar and honey for hair removal. The last technique likely helped with the bead-net dress vibe. Women took grooming seriously, and so did men.

Besides aesthetic value, cosmetics played a vital role in Egyptian cosmology. The symbology associated with cosmetics reflects this. The Natural History Museum of Utah explains that "various containers and palettes might be decorated with symbols associated with rejuvenation, or animal pigments might be ground into the makeup to imbue the wearer with some of their powers." But did the Egyptians devote time and energy to body painting? Not so much. Translation: jealous husbands who painted their concubines to ensure fidelity weren't really a thing.

The cult of Imhotep bears little resemblance to reality

"The Mummy" draws inspiration from the cult of Imhotep that developed after the real-life Egyptian's death (via Egypt at the Manchester Museum). But its depiction is only loosely based on the actual history of this cult. The movie worshippers of Imhotep are thugs looking to bring back the High Priest to exploit his power. But this goes against everything that real Imhotep cultists venerated about the guy.

What did followers of Imhotep appreciate most? They remained fundamentally fascinated by his incredible healing powers and wisdom. They also revered his intellect and ingenuity as a master builder for the pharaoh. But for some reason, the movies have confused this renowned scribe with a reanimated high priest who's an unstoppable force for revenge.

Embellishments aside, we've got to give Hollywood a break. After all, how fun would an adventure story be with a benevolent scribe and healer for an antagonist? Speaking from a dramatic perspective, inserting a hefty dose of lust, mayhem, murder, and afterlife revenge into the mix proves far more interesting. And isn't "The Mummy" ultimately all about thrilling the masses? As Roger Ebert reported after seeing the movie, "I cannot argue for the script, the direction, the acting or even 'The Mummy,' but I can say that I was not bored and sometimes I was unreasonably pleased. There is a little immaturity stuck away in the crannies of even the most judicious of us, and we should treasure it."