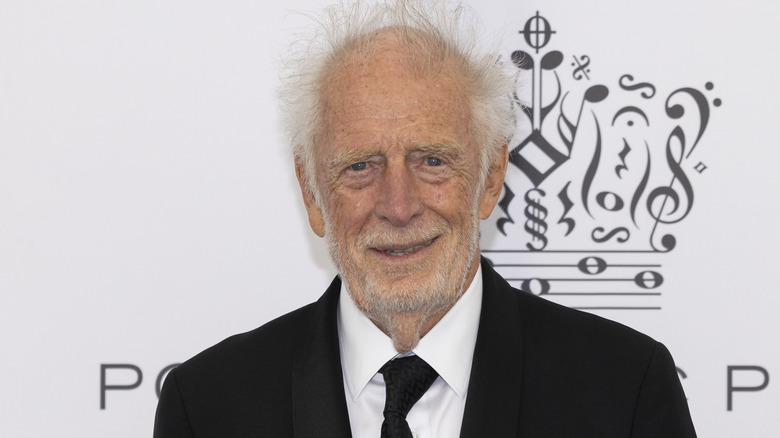

Whatever Happened To Bob Marley's Producer, Chris Blackwell?

The music of Bob Marley has been credited with taking reggae from Jamaica and turning it into a genre known around the world. But even the most talented musicians don't reach international fame without support. Marley and the Wailers' breakthrough came when they signed with Island Records, one of the most renowned independent music labels in Britain. And behind Island was Chris Blackwell.

It's Blackwell that the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame named "the single person most responsible for turning the world on to reggae music." And Jamaican music in turn gave the London-born Blackwell his start. His family had ties to the country, he spent most of his childhood there, and among his earliest records produced for Island — which he founded in 1959 — were Jamaican pop and folk music. These records filled a niche in the British music scene, and their success let Blackwell branch out.

When he met Marley in 1972, he had already signed the likes of Cat Stevens and Jethro Tull (Island distributed their singles for a few years prior). Blackwell has maintained a reputation for being a supportive, hands-off producer, but with Marley and the Wailers, he exercised a firmer hand in shaping their image to maximize their chances of success. The publicity-averse Blackwell was keen not to take credit away from Marley, but their association may be the most noted and fruitful of his career.

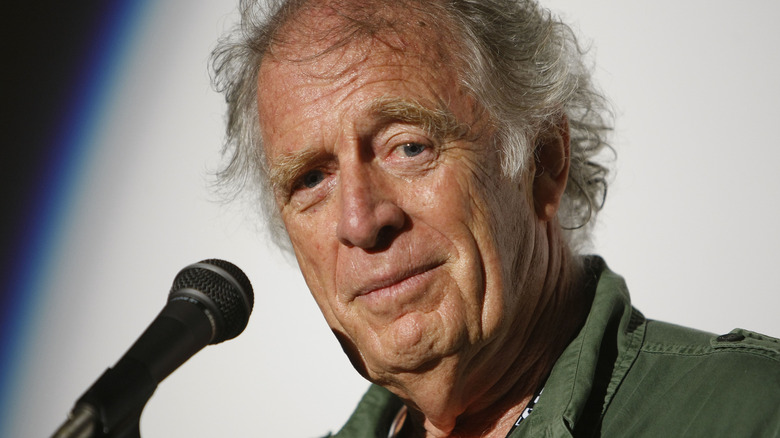

Blackwell also signed U2

Just a few years after meeting with Bob Marley, Chris Blackwell helped launch another legendary name in popular music: U2. Years later, he told Ultimate Classic Rock that if he had been sent a demo tape from the group, he never would have signed them. But his first exposure to the band was live, in a club with about 10 to 15 people. Even though their music wasn't to his taste, he appreciated their passionate performance — and the fact that they had a real manager who was serious about his job, not a talentless friend hanging onto the band. Based on both factors, Blackwell didn't hesitate to sign them.

The strength of Bono's personality in particular stood out to Blackwell, who recalls his first encounters with Bono and Marley in his memoir, "The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond." That strong personality occasionally clashed with Island management over the years. Bono and the rest of the band complained when Blackwell told them that an album photoshoot was no good, and they stood their ground when he objected to their bringing in Brian Eno as a producer. In both spats, it was Blackwell who stood down, deferring to the creative passions of his artists.

U2 appreciated Blackwell's support. Bono told The New York Times that the producer was a role model to him. And he and his bandmates were prepared to show their gratitude. When financial trouble in the mid-1980s left Island unable to pay them, U2 loaned the label money. In return, Blackwell gave them ownership of their masters and a percentage the company.

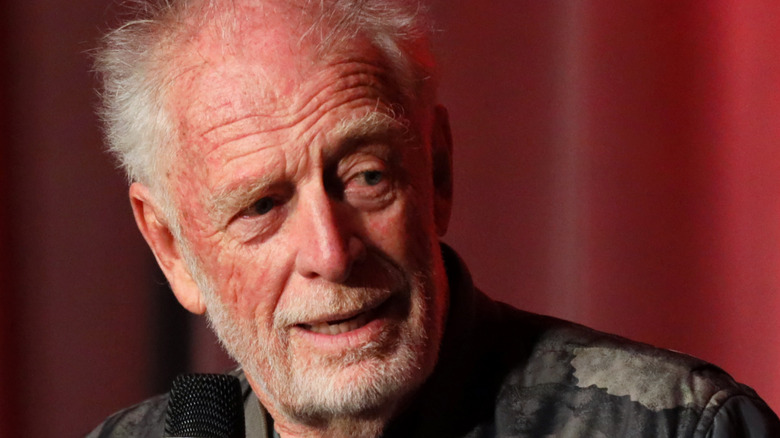

He has moved into media and tourism

Chris Blackwell has shouldered a portion of the blame for his 1980s money woes. He told Variety that he overspent on a failed movie project and ended up in trouble with Island Records. He also said that he wasn't prepared for how successful the label became. "It had gotten too big and too corporate for me and I couldn't really handle it," he said after selling his stake in the company (per The Irish Times). Amidst the various pressures, he decided to sell out to PolyGram for $300 million.

The sale wasn't the end of Blackwell's time in music. He remained attached to Island for another seven years and continued to sign artists. But his interests were shifting. A venture into tropical resorts under a new business, Island Outpost, commanded an increasing amount of Blackwell's time and energy, eventually becoming his primary business. He's described it as another way to give back to Jamaica, where many of his properties are based. Among them is GoldenEye, the home of James Bond creator Ian Fleming, with whom Blackwell's mother once had an affair.

Tourism has proved to be rewarding work for Blackwell, and while he appreciates the enduring success of Island artists, he told The Telegraph he doesn't spend much time looking back. Many of the independent labels that were contemporaries of Island's have been bought and shuttered. His advice for aspiring musicians in the current media landscape is to own their work, sell themselves, and be patient (via NPR).