The Truth About 1985's Live Aid Concert

Woodstock, once the largest music festival ever, was all but left in the dust by Live Aid on July 13, 1985. For 16 hours, and across multiple continents, dozens of the era's most popular bands and singers played primarily at the massive Wembley Stadium in London and JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, and at the same time. Beamed out live to at least a billion viewers in well over a hundred countries, that message of global connection was kind of the point of Live Aid. Conceived by Bob Geldof, a one-hit wonder that made millions with his band the Boomtown Rats, and Midge Ure of the New Wave band Ultravox, Live Aid was a multi-venue concert designed to raise awareness of, and vital relief money for, a deadly famine ravaging the African nation of Ethiopia.

The U.K. segment was kicked off by Prince Charles and Princess Diana, while in the U.S., iconic folk singer and '60s countercultural icon Joan Baez addressed the crowd, noting, "Children of the '80s, this is your Woodstock," (according to Audacy). In many ways, it was a definitive cultural experience for young people around the world. At the very least, it was a tremendous undertaking and historical event of note. Here's how Live Aid came together, went down, and made an impact on the world at large.

Live Aid was the next treatment after a Band Aid

In 1984, rock star Bob Geldof was watching a BBC news program and was horrified by a report on an ongoing famine in Ethiopia. By the end of that year, an estimated 1 million people in the African nation had died of starvation. Upset, agitated, and wanting to help, Geldof used his connections and pull and got together with Midge Ure of the band Ultravox to write "Do They Know It's Christmas?"

Geldof and Ure recruited the U.K.'s biggest acts of the time, including Bono, Sting, Duran Duran, and George Michael, to sing the charity single, credited to Band Aid. It was a smash hit, raised £8 million, and became a Christmas staple. Geldof was satisfied with his actions, but seeing as how the Band Aid project inspired other charity singles to raise funds for the Ethiopian famine, like USA For Africa's "We Are the World" in the U.S. and Northern Lights' "Tears are Not Enough" in Canada, Geldof realized he could make a lot more money with a concert.

In spring 1985, Geldof got concert promoters Harvey Goldsmith and Maurice Jones to put together a telethon that aired around the world. Live Aid would also be a concert, with separate shows in London and the U.S. The team had to work fast to acquire bands and set up the infrastructure, as it had just five weeks from announcement to showtime.

Philadelphia wasn't that odd of a choice

When plans for Live Aid were announced in advance, just weeks before the July 1985 music festival, the selection of Philadelphia as the site of the American side was somewhat controversial. Then, as now, it was not a major entertainment or media capital like New York City or Los Angeles, is fairly far inland, and lacked the large population of those other, seemingly more logical areas. "There are 100 U.S. cities that would have died to be the American standing grounds for Live Aid," declared the Scranton Times-Tribune in June 1985 (via Philadelphia Magazine).

But promoters and organizers had done their due diligence, concluding that Philadelphia actually did check all their boxes. For one, the city had to have a nearby international airport and be centrally located: Philadelphia is roughly equidistant from New York and Washington, D.C., creating a wide area from which to draw attendees. The city was also home to JFK Stadium, one of the biggest venues in the United States with a seating capacity of more than 100,000 (more than Wembley Stadium in London, poised to host Live Aid in Europe). Philadelphia's local government sweetened the deal by not charging Live Aid for the use of the stadium, as well as covering the cost of security and cleanup.

Live Aid included an ill-fated Led Zeppelin reunion

It must have been a tremendous surprise when Led Zeppelin took the stage during Live Aid at JFK Stadium in Philadelphia. The marketing materials hadn't mentioned the participation of the band, which had split up in 1980 after the death of drummer John Bonham.

The group — with Phil Collins and Tony Thompson of Chic on drums — played a 22-minute set, opening with "Rock and Roll," with Robert Plant warbling, "It's been a long time since I rock and rolled." That much was obvious — Plant was in no shape for the gig. "I was hoarse. I'd done three gigs on the trot before I got to Live Aid ... and by the time I got onstage, my voice was long gone." Plant later told Rolling Stone. The band hadn't rehearsed much either, for less than an hour, on the day of the performance, and without Collins.

Jimmy Page, meanwhile, was given a guitar right when he hit the stage, and it hadn't been properly tuned. He couldn't hear that, however, as the stage monitors weren't working properly. "My main memories, really, were of total panic," he recalled. According to Collins, Page's performance was additionally addled by his supposed inebriation. "It's immediately obvious that Jimmy is, shall we say, edgy," Collins wrote in "Not Dead Yet" (via Philadelphia Magazine). "It's only later when I watch the clip that I see him dribbling onstage — actual saliva. And he can barely stand up as he's playing."

Live Aid was really the Phil Collins show

Phil Collins became the singer for Genesis as well as its drummer following the departure of Peter Gabriel. In the 1980s, he launched a solo career as a soft rock artist, which was peaking right around the time that Live Aid happened in 1985. While the festival was lucky to secure the services of Collins at the height of his popularity, the singer-drummer was eager to help out with Live Aid wherever he could.

Having contributed drums to some of Robert Plant's solo records, Collins asked the singer if he could secure him a spot on the U.S. Live Aid lineup, because promoter Bill Graham wasn't a fan. It was Collins who suggested the collaboration be a full-on Led Zeppelin reunion. And then, Sting asked Collins to join him in his set at the London segment. That left the musician in a quandary — he couldn't play both shows, could he? U.K. festival producer Harvey Goldsmith arranged for Collins to take the Concorde, a high-speed supersonic jet, after his London performance, and head to Philadelphia in time to join Plant and Jimmy Page. Indeed, the pop star completed one set, sang with Sting, made the flight, helped Led Zeppelin briefly reunite, and then, having nothing but time on his hands, played with Eric Clapton during his set, too.

It marked the remarkable return of Teddy Pendergrass

Formerly the breakout star of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, Teddy Pendergrass went solo and became an absolute phenomenon in the world of soul and R&B. He racked up more than a dozen hit singles in the late 1970s and early 1980s, specializing in romantic and sultry slow jams like "Close the Door," "Turn Off the Lights," and "Love TKO." But then Pendergrass's career came to a sudden halt in 1982 after an accident that nearly cost him his life. Pendergrass lost control of his car while driving in Philadelphia and struck a tree with such force that he sustained injuries that left him mostly paralyzed, unable to use his limbs.

His recovery was slow and arduous, and Pendergrass retreated from view for a long period. His re-emergence as a public figure and performing artist at Live Aid became one of the festival's most memorable moments. During soul duo Ashford and Simpson's set, Nick Ashford announced that a special, unannounced guest was going to join them for a song. The song was Diana Ross's "Reach Out and Touch (Somebody's Hand)," and the guest was Terry Pendergrass, who emerged onto the stage, using a wheelchair, greeted by the rapturous applause of the crowd in his hometown of Philadelphia.

Welcome to Live Aid, here's Bernard Watson

Live Aid got started at noon, London time, with "Rockin' All Over the World" by Status Quo. Hours later, when the show continued in Philadelphia, the first performer was a complete unknown: David Weinstein, an 18-year-old aspiring musician who performed under the stage name of Bernard Watson.

After graduating from high school in Miami a few weeks earlier, he drove up to the northeast to see friends and then planted himself in Philadelphia with a goal in mind: get Live Aid promoter Bill Graham to give him a spot in the music festival's lineup. To show he was serious, Weinstein recorded a demo tape of a few of his songs, singing and accompanying himself on acoustic guitar. For 10 days, he stationed himself outside the concert venue, JFK Stadium, sleeping in his car and keeping an eye out for Graham. One day, he spotted Graham, handed over the tape, and some time after that, the promoter found Weinstein in his car. Graham told the musician that he was a little rough for Live Aid. After sending a Rolling Stone reporter to profile him (and a prime rib dinner), Graham gave Weinstein, or Watson, the chance to play in front of 100,000 people at the start of Live Aid, just before 9 a.m. Weinstein never pursued music again.

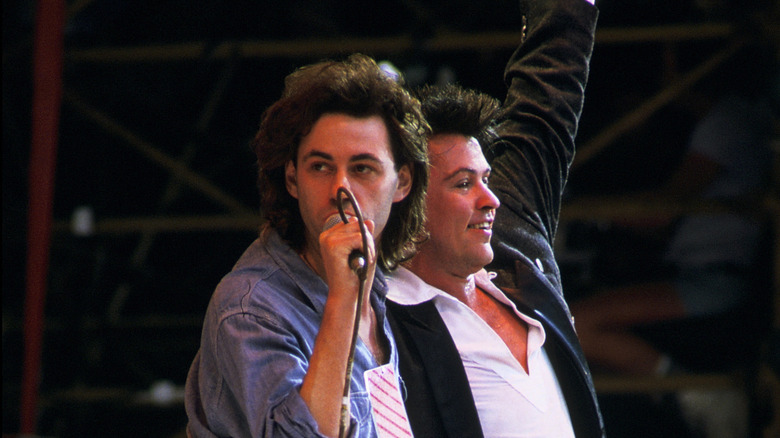

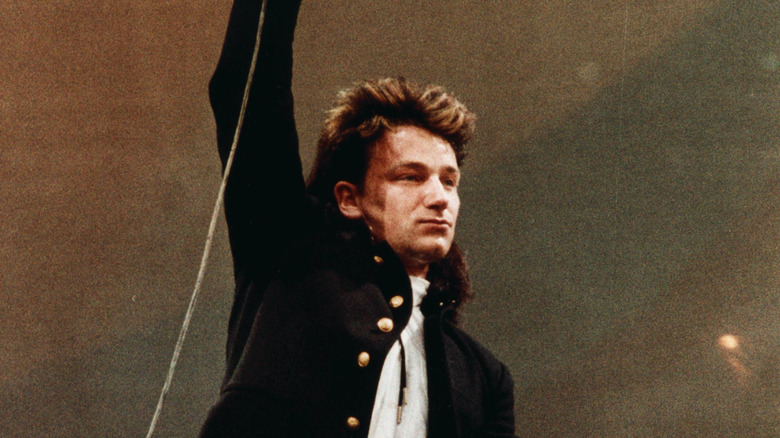

Live Aid helped make U2 into superstars

When U2 was booked to play Live Aid, the epic, politically and spiritually charged rock band from Ireland was a group of rising stars with a modest following in the U.K. and one minor hit in the U.S. Its electric and crowd-engaging set at the London portion of Live Aid would instantly elevate the band's profile; just a couple of years later, it would be arguably the biggest band on Earth.

U2 played just two songs during its slot: "Sunday Bloody Sunday" and "Bad," although the latter was a freewheeling jam that went on for 14 minutes and included parts of the Rolling Stones' "Ruby Tuesday." During that time, lead singer Bono solidified his stage persona of a gregarious, unifying party animal who worked the crowd. At one point, he invited up a couple of women to the stage to hang out. Bono also apparently helped save a life. He leapt from the stage into a fenced-off area and implored security guards to lift a young woman over a barricade. The rock star briefly danced with the woman and kissed her on the cheek.

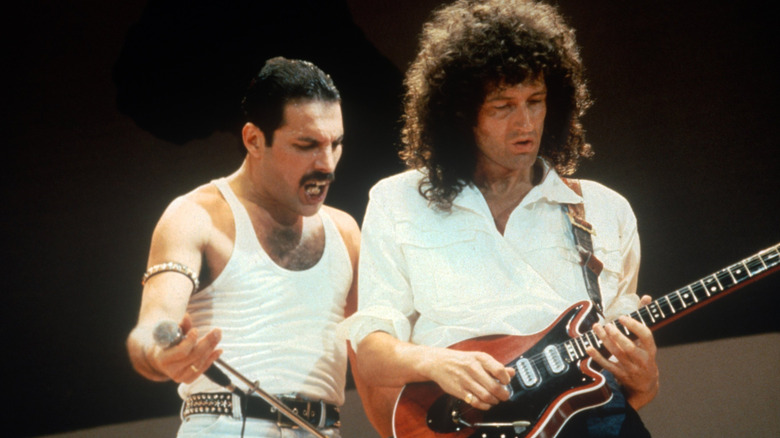

Queen put on a great show

Queen's triumphant and commanding performance at Live Aid was a moment from the '80s rock scene that will never go out of style. Probably the most memorable music festival mini-set in rock history, the set is so legendary that 36% of poll respondents say it's the iconic concert they most wish they could have seen. Queen was on the stage at Wembley Stadium for only about 20 minutes, which was more than enough time to make history.

Dressed in a matching white tank top and pants, singer Freddie Mercury absolutely dominated, belting his way through tightly constructed iterations of Queen classics "Bohemian Rhapsody" and "Radio Ga Ga," seemingly attempting to produce the full Queen concert experience in a limited timeframe. Before starting up the newer song "Hammer to Fall," Mercury invited the audience to participate in "Ay-Oh!" — a joyful call-and-response and quintessential part of the Queen live show. While Queen was well-liked at the time, by 1985 the band was considered a little passé; Live Aid reminded the world that it was still a tremendous live act.

Live Aid was riddled with live gaffes

There's a lot that can go wrong at a concert, but with all the complicated audiovisual equipment, musical instruments, and electrical needs at play, it stands to reason that the bigger the concert, the greater the chance for technical disaster. As Live Aid was one of the biggest concerts ever, it subsequently suffered numerous mishaps.

Crosby, Stills, and Nash, whose sound depends so much on vocal harmony, were criticized for their out-of-tune singing; monitors didn't work correctly, and so the singers couldn't even hear one another during the performance. The Who's set wound up being performed primarily for live show attendees only, as the satellite uplink failed to globally transmit two of its four songs. During a spontaneous performance of the protest anthem "Blowin' in the Wind," Bob Dylan broke a guitar string. One of his backing musicians, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, gave Dylan his guitar to use, then played air guitar awkwardly while he waited a good long while for a tech to bring him a new instrument. When second-to-last London act Paul McCartney began his slot, the sound system went out entirely, requiring engineers to go on the stage and turn it on by hand.

Many bands shouldn't have bothered to reunite at Live Aid

Live Aid was the biggest event of the year, and it supported a noble cause. That made the lure of performing at the festival irresistible, even to inactive bands. Audiences were definitely excited when Live Aid hosted the reunification of Black Sabbath with its original lead singer, Ozzy Osbourne, fired in 1979 for his persistent substance abuse issues. The results — renditions of classics "Iron Man," "Paranoid," and "Children of the Grave" — were less than glorious. "We got to the rehearsal space and were supposed to rehearse three songs. Instead of doing that we ended up talking about old times," guitarist Tony Iommi wrote in "Iron Man" (via Rolling Stone). "We went back to the bar afterwards, had a great time together and got solidly sloshed." The lack of preparation and prodigious consumption of booze were apparent during Black Sabbath's set: Iommi and Osbourne were both visibly and egregiously hungover.

Another marquee reunion was The Who, regrouping for the first time after a 1982 goodbye tour. Strong-armed into playing by organizer Bob Geldof, who calculated that the band's brief appearance could raise enough money to translate to a million saved lives, the Who neglected to rehearse. The musicians didn't sound on the same page musically, and were stymied by problems like bassist John Entwistle's malfunctioning instrument.

Where did all the money go?

There are scientific reasons behind why we feel happy at concerts, and those positive emotions were flowing in full force at Live Aid. Beyond just having a good time and watching some of the biggest acts in the world play, fans had gathered to support the cause: Ethiopian famine relief. Those watching at home were moved, too, and to donate. When all the money promised was sent in and counted, Live Aid had raised $125 million.

A lack of food for millions of people is a complicated and expensive issue to address, but $125 million is unquestionably a lot of money that could have alleviated the famine in some way. Instead, those hard-won life-saving funds virtually disappeared in the months after Live Aid. Scarcely and under-reported in the U.K. and the United States was that the famine wasn't just the result of a horrific 1984 drought that decimated the Ethiopian food supply. It was also in the midst of a civil war, and the head of the establishment, the dictatorial Mengistu Haile Mariam, didn't use the fortune given to him to feed his people.

Instead, Haile Mariam bought stockpiles of military-grade weapons from the Soviet Union, which he used to help quash the uprising against his government. Geldof was even told that such a thing might happen before Live Aid, warned by humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières to not allow Ethiopia to access the money without a fair and reputable distribution system in place.

Technically, Live Aid was a massive achievement

Organizers of Live Aid knew that if they had any chance at all of earning tens of millions of dollars to feed starving people in Ethiopia, they'd have to attempt one of the biggest broadcasts in history. "The logistics of this thing are staggering," organizer Bob Geldof told The New York Times before Live Aid happened in July 1985.

The festival was one continuous multi-act concert held in two cities, first in London and then picking up in Philadelphia, over the span of 17 hours. Thanks to the use of 13 military-grade satellites, it reached 1.9 billion potential viewers, who also saw performances from other countries, including the Soviet Union, which allowed a live rock show on its state-run airwaves for the first time. In all, Live Aid was seen in about 150 countries.

In the U.S., MTV aired all 17 hours from London and Philadelphia. For households that hadn't yet signed up for cable TV, which was still considered an expensive novelty, ABC aired a three-hour portion in primetime and most of the day was carried on ABC Radio affiliates. But the point of it all was to raise funds, and organizers convinced AT&T to donate, free of charge, a 1-800 number that viewers could call to donate money, with 1,100 operators standing by. Other big numbers from the American side of Live Aid include the 200 police officers who kept the peace at JFK Stadium, along with 900 private security personnel.