How The Ideas Of Original Intent And Original Meaning Impact The Supreme Court

The United States Supreme Court, as its name suggests, is the highest court in the nation. As such, it has the power of "judicial review," or the ultimate say as to whether or not a law or executive action violates the U.S. Constitution, according to the Supreme Court's website. But how should it interpret a document written more than 200 years ago? One school of thought is originalism, the idea that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its original meaning (via The Conversation).

Within originalism, there are two distinct schools of thought. Original intent holds that the Constitution should be interpreted according to what the document's authors themselves intended when they penned it, as one scholarly article published by the Northwestern University Law Review outlined in 2019. Original public meaning, on the other hand, is the belief that it should be interpreted according to what a reasonably well-educated person reading it at the time would have understood.

Unifying the two schools of thought within originalism

While original intent and original public meaning are seen as two distinct ways of interpreting the Constitution, scholars John O. McGinnis and Michael B. Rappaport argued in their article "Unifying Original Intent and Original Public Meaning," published by the Northwestern University Law Review in 2019, that it is possible to make them work together. Why? Per both, the framers would have intended people to understand the text's meaning using common "interpretive rules" — ones available to everyone at the time. Original public meaning is usually sussed out by coming to understand the strategies that a reasonable and informed person would have employed at the time to make sense of the text, so it is possible for justices to determine both original intent and original public meaning in the same way.

Justices can determine original public meaning in various ways, according to the National Constitution Center. They can consult legal documents — along with lexicons, dictionaries, and grammar books of that time — to provide linguistic context and cues in order to piece together what might have influenced the Constitution's language. They can also use these to study debates or legal battles that might have influenced any given particular provision. Overall, the point is to understand the document within its original context. Arizona State University Associate Professor of Law Ilan Wurman compared the process to following an apple pie recipe from 1789 (via The Conversation).

Interpreting the Constitution as a living document

Originalism is typically opposed to the theory of what is called "living constitutionalism," according to the National Constitution Center. Living constitutionalism argues that the document's meaning evolves alongside the national public's social attitudes. For living constitutionalists, a formal amendment does not need to be added to the Constitution in order to enshrine this change in meaning.

The National Constitution Center gives one important example of the difference between the two schools of thought: the issue of racial segregation as reflected through two historic rulings. Living constitutionalists argue that racial segregation was constitutional in the U.S. until the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. In this landmark case, the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools violated the Constitution (via History). This reflected a change in public attitudes that meant that racial segregation was no longer acceptable to the U.S. public and therefore no longer constitutional. Originalists, on the other hand, hold that racial segregation was unconstitutional as soon as the 14th Amendment was passed in 1868, according to the National Constitutional Law Center. Following that throughline, the Supreme Court's earlier decision of Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld segregation in 1896, was therefore always unconstitutional.

Waves of originalism

History is mixed when it comes to what originalism means for the Supreme Court in practice. As Vox noted in a 2020 write-up about how originalism relates to the current conservative-heavy SCOTUS line-up, this is evidenced by the three distinct waves of originalism on the Supreme Court. The first wave was led by liberal Franklin D. Roosevelt appointee Senator Hugo Black. Black used originalism to argue against the attempts of conservative justices to restrict the federal government's ability to regulate the economy — especially when it came to labor laws — and argued that these judges were overreaching in their interpretations. He also used originalist arguments to rule that the Bill of Rights should apply to states as well as the federal government. However, he dissented from the 1965 decision on Griswold v. Connecticut, which overturned a state law banning married couples from using contraception. While Black did not personally agree with the laws, he said the text of the Constitution did not include the "right to privacy" that the decision rested upon.

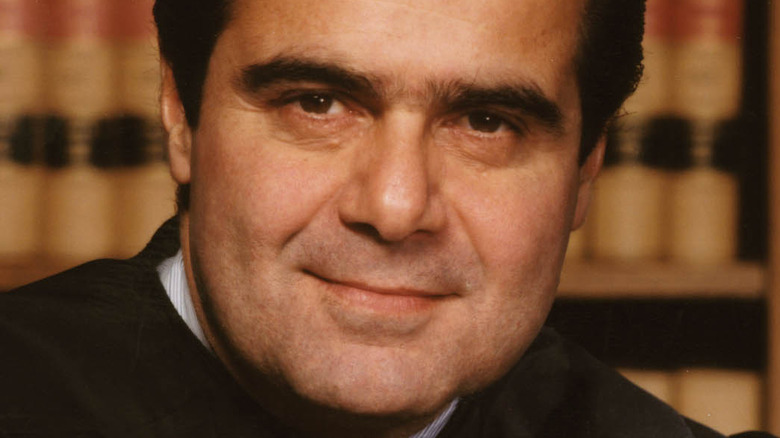

The second wave of originalism was led by conservative SCOTUS Justice Antonin Scalia, as explained by Think Progress. While Black had turned to originalism to push back at what he saw as conservative overreach, Scalia argued that the Supreme Court had overplayed its hand with liberal decisions like Roe v. Wade, which granted abortion rights in 1973. However, he largely based his arguments on the principle that the Supreme Court shouldn't exceed its mandate.

The third wave of originalism

The third wave of originalism, like its prior iteration, is conservative in nature — but different in that it places less emphasis on judicial restraint, according to both Vox and Think Progress. While Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia argued that issues like abortion should be resolved by the democratic process instead of through the courts, third-wave originalists are more likely to use the Constitution against decisions made by the other branches of government. As a member of SCOTUS, Scalia was instrumental in crafting an important aspect of contemporary originalism: The shift from focusing on original intent to original public meaning, which he began advocating for in 1986 (via The Christian Science Monitor).

This interpretive shift gave originalists on the Supreme Court more freedom. "Sitting here in the present day using books and articles from a long, long time ago to decide what a provision of the Constitution means [gives judges] a lot of discretion," Loyola Law School professor Kimberly West-Faulcon explained to The Christian Science Monitor in 2021 about how originalism can be wielded.

Today, third-wave originalism is represented on the Supreme Court by Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett. Per Vox, their opinions and statements reveal how much disagreement there actually is in determining the original meaning of the Constitution. Thomas, for example, believes the Constitution opposes the labor laws that Black used it to defend. Coney Barret, meanwhile, said in a Journal of Constitutional Law article that Brown v. Board of Education could actually be considered unconstitutional from an originalist perspective.

Originalist decisions made by SCOTUS today

Has third-wave originalism actually influenced any Supreme Court decisions? Writing in 2021, The Christian Science Monitor said that the 2008 ruling on the case District of Columbia v. Heller was the sole majority originalist decision the Court had made up until that point. For the uninitiated, the Supreme Court ruled that Washington, D.C. laws restricting handgun ownership violated the Second Amendment right to bear arms. SCOTUS argued this right extended to individuals outside of militias by citing the grammar of the Second Amendment, amendment drafts, similar laws from state constitutions at the time, and contemporary interpretations of the amendment by scholars, legislators, and the courts.

The Court's decision overturning Roe v. Wade in June 2022 also has originalist overtones. It echoes both Hugo Black and Antonin Scalia in denying a constitutional right to privacy. "Roe, however, was remarkably loose in its treatment of the constitutional text. It held that the abortion right, which is not mentioned in the Constitution, is part of a right to privacy, which is also not mentioned," Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the majority opinion (via the Associated Press).