The Untold History Of Roe V. Wade

On May 3, 2022, a draft opinion of the United States Supreme Court was leaked, which strongly suggested that the Court was planning to overturn the right to have an abortion in the United States, stating that "We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled."

The right to abortion wasn't always a hot-button political issue. During the 1970s, the religious right rallied around anti-abortion after they lost the battle of school segregation. But this wasn't the first assault on abortion rights and reproductive justice in the United States.

Abortion has been practiced by people on the North American continent well before the inception of the United States, and even after American independence, abortions were considered commonplace. But if reproductive agency was once a normal practice, what caused the shift into criminalizing abortions to the point where the Supreme Court had to eventually get involved and legitimize the right to abortion? And what happened after that decision? This is the untold history of Roe v. Wade.

Before the quickening

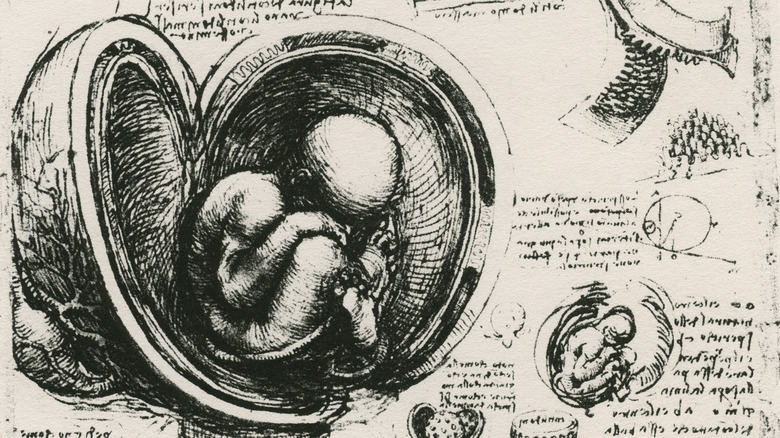

During the American colonial period, colonies followed British common law when it came to abortion. This meant that abortion was loosely regulated, but only after the "quickening." The idea of the quickening, or the point when a pregnant person can feel the movements of the fetus, can be traced back to Aristotle and was considered to be the developmental stage that separated the embryo from the fetus, according to The Embryo Project Encyclopedia.

In colonial America, there's reportedly only one documented case of a surgical abortion, according to "Women in Early America" by Dorothy A. Mays. In 1742, Sarah Grosvenor tried to induce an abortion several times by ingesting herbs. When they didn't work, she went to a "physick" who tried to induce a surgical abortion, but unfortunately Sarah died as a result. After her death, both the doctor and her lover were tried for her death, but they were both acquitted.

In "The Changing Voice of the Anti-Abortion Movement," Paul Saurette and Kelly Gordon write that after independence, American states ended up basing many of their laws on British common law, including their abortion laws: "To the extent that abortion was subject to legal regulation, the standards were relatively permissive and what law existed was difficult to implement and thus rarely enforced," and those laws only really kicked in after the quickening. In addition, because procedures related to reproductive health were rarely discussed and left up to midwives and medical practitioners, drugs that could induce abortion were "widely and publicly available on the market."

Abortion as enslaved rebellion

During the period of enslavement in the United States, Black people used a variety of methods to maintain reproductive agency or keep their children from being enslaved, ranging from avoiding sexual contact, inducing abortions, and infanticide. Across cotton plantations, some enslaved people chewed cotton roots to prevent pregnancy or induce an abortion. Others used calomel, also known as mercurous chloride, or turpentine. "In them days the turpentine was strong and ten or twelve drops would miscarry you. But the makers found what it was used for and they changed the way of making turpentine. It ain't no good no more," per the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative.

According to the PSU McNair Research Journal, because any successful attempt to limit reproduction "a loss of capital for their master, and a loss of population for the system itself [...] any reproductive choices that slave women made could affect their system of oppression and, therefore, should rightly be deemed as resistance to slavery."

But as Black Perspectives notes, there are unfortunately few records of the views of enslaved people regarding abortions. This is due to the fact that Black people would have to recount their experiences of slavery to interviewers or editors who were white men, which "limited their ability to speak openly about birth control and contraception."

The first anti-abortion laws

The very first state to pass legislation that explicitly outlawed abortion after the quickening was Connecticut in 1821, making a direct reference to a person being "quick with child." Other states followed suit, but as "The Changing Voice of the Anti-Abortion Movement" notes, many of these early laws didn't punish the person who had the abortion and instead targeted the apothecaries that sold abortifacients. But despite these laws, marriage manuals published through the 1830s continued to offer tips on abortions.

The Duke Law Journal writes that, almost 25 years later, New York State passed one of the first laws that actually criminalized the person having the abortion in 1845. The law stated that those who took an abortifacient or underwent a surgical abortion before the quickening were guilty of a misdemeanor while those who induced an abortion after the quickening were guilty of a felony, according to "A History of the U.S. Political System." Before long, 14 other states had also adopted similar abortion laws.

Common practice in the 19th century

Despite the anti-abortion laws enacted in the United States, abortion remained relatively common practice in the 19th century. According to "Abortion in America" by James C. Mohr, in the 1850s, it was estimated that one in every five pregnancies resulted in an abortion. Other estimates indicated that roughly 2 million abortions were performed in the United States every year. And even with the increasingly common anti-abortion laws, few doctors or midwives were ever arrested or convicted unless the person who had the abortion died, writes The Atlantic.

There were many abortion providers in the United States, but the most famous of them was Ann Trow, also known as Madame Restell. The Embryo Project Encyclopedia writes that Restell would provide herbal treatments by mail to induce abortions, with plants used for centuries for abortions, such as "pennyroyal, savin, black draught, tansy tea, cedar oil, ergot of rye, mallow, and motherwort."

Restell charged financially insecure people $20 for an abortion while wealthy women were charged $100. This amounts to roughly $660 to $3,300 in 2022, and is not unlike the cost of abortions in the 21st century. Restell reportedly provided abortions for up to 35 years, with offices in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. In addition to providing abortion services, Restell also provided aid to people who wanted to carry the pregnancy to term. She offered a boarding house where people could give birth and afterwards would facilitate the adoption for an additional fee.

Physicians against reproductive rights

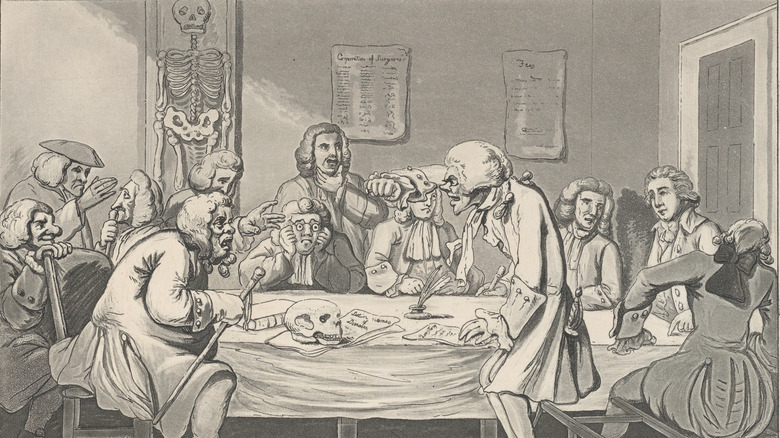

One of the strongest opponents to abortion to come out during the mid-19th century was the American Medical Association (AMA). Formed in 1847, the AMA was formed by wealthy doctors who wanted to monopolize the market and legitimize only their method of practicing medicine, especially when it came to abortion services, which often fell under the purview of midwives.

In "Opposition and Intimidation," Alesha Doan writes that the AMA formally began its fight against abortion in 1859, when they passed an anti-abortion resolution. In addition to lobbying judges, lawyers, and state legislatures, the AMA also launched a public battle, reportedly holding a contest in 1864 "challenging doctors to write anti-abortion books designed for the general public to understand." It was during this time that doctors began contesting the notion of relying on the quickening, claiming that women were unknowingly ignorant that they were committing a sin because they were following the English legal tradition. Physicians claimed that they were the ones with expertise, despite the fact that midwives had been in the profession for centuries, and sought to move abortion into entirely their own purview.

According to "The Changing Voice of the Anti-Abortion Movement," the medical community wasn't the only voice in the anti-abortion movement. Racists and eugenicists also challenged people's reproductive agency, claiming that the influx of non-white immigrants would soon outnumber white Americans and that access to contraceptives and abortion "threatened Anglo-Saxon Protestants who wanted to maintain control over American society."

The Comstock Law

Following the assault by physicians and racists, Congress passed the Comstock Law of 1873, named after Anthony Comstock, the head of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. PBS writes that The Comstock Act defined contraceptives and abortifacients as obscene, and it was a federal offense to send anything that could be considered obscene, indecent, or immoral through the mail. The punishment included imprisonment between six months and five years or a fine between $100-$2000. This was reportedly the first law of its kind in the Western world, and after the federal law was passed, 24 states followed suit and enacted state legislation as well to restrict the trade of contraceptives and abortifacients.

According to The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, the Comstock Act was enforced until it was overturned by the decision in Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, which held that it was "unconstitutional to restrict access to birth control because it interfered with a person's right to privacy."

But by the beginning of the 20th century, every state in the United States had outlawed abortion, though there were some differences between the states as to what exactly was prohibited, such as exceptions if the life of the pregnant person was at risk, among other things.

Death rates rise

With the rise in anti-abortion laws and messaging, people didn't stop seeking out abortions. But their illegality made it much more difficult to procure safe abortions and as a result, maternal mortality rates rose. The CDC reports that in the 20th century, pregnancy-related deaths were highest from 1900 to 1930, during which time at least half of pregnancy-related deaths that were due to sepsis, about half of which were the result of induced abortions.

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition writes that although there's little reliable data about pregnancy-related deaths in the United States before 1915, "thereafter, the United States had the highest rates of maternal mortality of any developed country." In "Lessons from Before Roe," Rachel Benson Gold writes that in 1930, abortion was listed as the official cause of death for over 2,500 people — roughly 18% of pregnancy-related deaths that year.

And according to the 1976 congressional hearings on abortion, in the 1960s, between 40-50% of pregnancy-related deaths in states like New York, Pennsylvania, and Michigan were due to abortions that people had sought, despite them being illegal. The official death toll declined over the decades, likely due to the introduction of antibiotics, but even in 1965, abortions accounted for 17% of pregnancy-related deaths.

Hawaii's decriminalization

On March 13, 1970, Hawai'i became the first American state to legalize abortion, allowing it to be performed if requested by a pregnant person as long as it was performed in a hospital by a licensed doctor before 24 weeks. However, according to the University of Hawai'i, it was also required a person to be a resident of the state for at least 90 days. Up until then, abortion was only allowed in Hawai'i if it was necessary to save the life of the pregnant person.

According to the 1976 congressional hearings on abortion, there were over 3,500 abortions performed in Hawai'i in the first year after legalization. And "there is considerable evidence that the present demand was not the product of the legalization, but had existed for some time prior to it."

In April 1970, New York also voted to legalize abortion, allowing them to be performed up through the first 24 weeks of pregnancy. But according to CQ Researcher, New York's law had neither a residence requirement nor a hospital requirement.

Two Supreme Court cases

Three years after states began legalizing abortions, the United States Supreme Court ruled on two landmark cases that effectively decriminalized abortion on a federal level. The first of these cases is the well-known Roe v. Wade, which struck down the anti-abortion law in Texas on January 22, 1973. According to the Liberty University Law Review, with Roe v. Wade the Supreme Court ruled that anyone "could have an abortion during the first six months of pregnancy for any reason [they] dee[m] fit."

The second case is Doe v. Bolton, which overturned the abortion law in Georgia and whose decision was also released on January 22. The Embryo Project Encyclopedia writes that the Doe v. Bolton ruling upheld the reasoning used in Roe v. Wade and added to it, finding that the requirement for hospital accreditation "restricted access to abortions unduly." In addition, the residency requirement was also ruled to be unconstitutional.

The New Mexico Law Review writes that the Supreme Court used the trimester framework in their decision. During the first trimester of pregnancy, the state was considered to have no authority to regulate abortions. During the second trimester the state could regulate the procedure as long as the regulation was "reasonably related to maternal health," and only in the third trimester did the state have justification for regulation for the purpose of protecting "potential human life."

The right to privacy

Both of the Supreme Court decisions regarding abortion were based on the right to privacy that was established by the 14th Amendment. According to the New Mexico Law Review, the Supreme Court stated in their decision that "the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision," although they also asserted that "this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation."

However, as Caitlin E. Borgmann notes in "Abortion, the Undue Burden Standard, and the Evisceration of Women's Privacy," this right to privacy was largely based around the doctor's office, considered to be the only appropriate private realm, and the Supreme Court seemed to be more concerned with "the right of the physician to administer medical treatment according to his professional judgement," than about underlining the agency of the pregnant person.

Abortion isn't the only thing that the Supreme Court determined falls under the right to privacy, though. Griswold v. Connecticut, which protected the ability of married people to buy contraceptives, Lawrence v. Texas, which found that it was unconstitutional to punish people for homosexuality, and Loving v. Virginia, which struck down interracial marriage bans, were all decided based on the idea of the right to privacy.

Overturning the trimester framework

Less than 20 years after adopting the trimester framework, the Supreme Court ended up rejecting the framework in Casey v. Planned Parenthood. According to the University of Baltimore Law Forum, in Casey v. Planned Parenthood, the Supreme Court stated that instead of the trimester framework, "the constitutionality of abortion regulations before fetal viability must be judged by an 'undue burden' standard." This meant that although the Supreme Court continued to recognize a person's right to an abortion, it held that the state is within their rights to try to persuade people to choose childbirth over abortions "so long as those measures do not constitute an undue burden on the exercise of that right."

According to "The Changing Voice of the Anti-Abortion Movement," the decision in Casey v. Planned Parenthood is considered to be one of the first returns to abortion restrictions because it made it easier for states to enact them. In rejecting the trimester framework, the Supreme Court decided that states have an interest in early fetal life, rather than limiting the state's influence to the third trimester, allowing states to introduce regulations on abortions as early as the first trimester. And by allowing states to push a preference for childbirth over abortion, this led to a variety of informed consent laws, ultrasound viewings, and mandatory waiting periods in regards to abortions. It also allowed anti-abortion activists to push the narrative that people don't willingly choose abortions.

Anti-abortion terrorism

After abortion was legalized in the United States through Roe v. Wade in 1973, there was a violent backlash. Anti-abortion terrorists proceeded to target places that offered abortions, resulting in thousands of violent incidents. According to the National Abortion Federation, between 1977 and 2014, anti-abortion terrorists committed at least eight murders, 17 attempted murders, 42 bombings, 100 butyric acid attacks, 182 arson attacks, 663 anthrax or bioterrorism threats, and four kidnappings.

In 1996, anti-abortion terrorist Eric Rudolph made headlines after he bombed the Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta, Georgia on July 27 during the 1996 Summer Olympics. The shrapnel from the bombing killed Alice Hawthorne and injured 111 other people, Atlanta Magazine reports. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution writes that in addition to bombing the 1996 Summer Olympics, Rudolph also bombed two clinics that provided abortions, one of them in Birmingham, Georgia, as well as an Atlanta lesbian bar.

After he was arrested, Rudolph pled guilty to the bombings and released an 11-page statement in which he cited abortion, gay rights, and the federal government as the motive for his attacks. In his statement, he claimed, "Abortion is murder. And when the regime in Washington legalized, sanctioned and legitimized this practice, they forfeited their legitimacy and moral authority to govern," per NPR.

Abortion in the 21st century

After the increase in abortion restrictions after the Casey v. Planned Parenthood ruling, people didn't stop getting abortions. Instead, states started prosecuting people for miscarriages and stillbirths, since it's almost impossible to tell the difference between an abortion and a miscarriage, also known as spontaneous abortion. According to The New Republic, since abortion was legalized in 1973, up to 1,600 people have "faced criminal punishment for the outcomes of their pregnancies." Out of these, 1,200 prosecutions occurred after 2006, and these prosecutions disproportionately target Indigenous, Black, non-white, and financially insecure people.

One such case was the conviction of Brittney Poolaw, a member of the Comanche Nation, who was convicted in 2021 of second-degree manslaughter for a miscarriage and was sentenced to four years imprisonment, NBC reports.

In 2019, Marshae Jones, a Black woman in Alabama, was also charged with manslaughter after being shot in the stomach while pregnant. According to The New York Times, the police claimed that she was responsible "because she started the fight that led to the shooting and failed to remove herself from harm's way." Meanwhile, no charges were filed against the person who actually fired the gun. The manslaughter charge against Jones was eventually dropped by prosecutors.

The Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade

On June 24, 2022, almost exactly 50 years after the Roe v. Wade ruling, the Supreme Court handed down its decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health. In a 6-3 vote along ideological lines, the court overturned both Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, meaning there was no longer a federal protection of the right to end a pregnancy in the United States.

"Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences. And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division," Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote for the majority, per The Washington Post. "It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people's elected representatives."

However, CNN reports that the pro-choice movement was given a poignant note in the dissent from the three liberal justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, who closed out their dissent with the line: "With sorrow — for this Court, but more, for the many millions of American women who have today lost a fundamental constitutional protection — we dissent."