The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Joy Division

This article contains discussions of mental health and suicide.

Born out of Manchester, England, in the mid-1970s, post-punk band Joy Division left a legendary impression on the music industry, influencing various genres, from alternative rock groups like The Killers to dance and electronic artists such as Moby (via The Guardian). Even more incredible: Joy Division was active for a mere four years, never truly reaching the full scope of their potential before frontman Ian Curtis' suicide in May 1980, per the Independent.

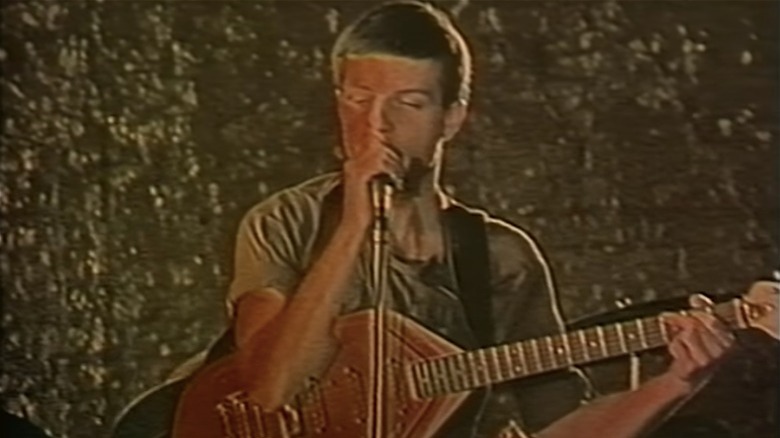

Joy Division's lineup consisted of Curtis, lead singer and lyricist, Bernard Sumner, guitarist and keyboardist, bassist Peter Hook, and drummer Stephen Morris. According to Far Out magazine, the band came to be after Sumner and Hook attended a Sex Pistols concert in June 1976. Inspired by the group's punk ethos, the two decided to form their own band, and after a few small performances, the men posted an ad for a vocalist. Curtis joined the band shortly after, and by May 1977, they played yet another show under the name Warsaw. After cycling through a few other drummers, Morris finally rounded off the quartet.

Sadly, Joy Division only had the chance to release two full-length albums. "The music and the story — it's a myth, isn't it?" recalled Morris to the Independent, adding, "what you see is all there is and you can make your own story." Their story is a melancholy one — but it's also incredibly inspiring. This is the tragic real-life story of Joy Division.

Growing up in Manchester was bleak for Joy Division

The men of Joy Division grew up in the suburbs surrounding Manchester, England, in the 1960s. Back then, the city was drastically different from what it looks like today. "In the '60s and '70s, [Manchester was] a crumbling remnant of the industrial revolution, where slums were demolished to make way for bad modern housing," explains the BBC documentary, "Factory: Manchester from Joy Division to Happy Mondays," further revealing how dark and dirty it was.

And yet, Manchester was the perfect place for Joy Division's sound to develop. "Joy Division sounded like Manchester: cold, sparse, and, at times, bleak," wrote Bernard Sumner in his biography, "Chapter and Verse: New Order, Joy Division and Me." After the band formed in 1976, they began practicing in a cold, derelict mill, which, as Stephen Morris recalled to Vice, was the only space the working-class band could afford. Nevertheless, working with zero inspiration made Joy Division focus on the only thing that mattered: their music.

Interestingly enough, as Morris remembered, the band would regularly tell those that listened to their early songs that they weren't a depressing band — the young men were just enthusiastic about being able to make music. Decades later, however, after re-releasing their albums and listening to the tracks again, certain melodies and themes seemed incredibly apparent: "How the bloody hell did I think we were anything else?" (via Vice).

The sad story behind She's Lost Control

"She's Lost Control," from Joy Division's first album, "Unknown Pleasures," is one of the band's most well-known songs. With its detached drum beat and Ian Curtis' dark vocals, the song is catchy, albeit bleak, growing progressively more unhinged as Curtis belts out the words. As for the lyrics themselves, they're hauntingly prophetic for the talented vocalist.

According to RadioX, although Joy Division was formed in 1976, the men still worked their day jobs for a few years after the band's inception. For Curtis, that consisted of working at a job center that focused on finding employment for those with special needs. One of his clients was diagnosed with epilepsy, and during various visits throughout 1978, she had intense seizures, no doubt shocking the young man (via Far Out). When she stopped coming to see him one day, Curtis assumed the woman had found a job yet ended up discovering that she had a fatal seizure in her sleep.

Inspired by what he had witnessed, Curtis wrote the words to the now-iconic track, with haunting lyrics such as, "Confusion in her eyes that says it all / She's lost control / And she's clinging to the nearest passerby / She's lost control." By late December 1978, Curtis experienced his own very first epileptic fit (via RadioX).

Their early days playing shows weren't exactly successful

After attending the now-famous Sex Pistols concert at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in June 1976, Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook were entranced with the concept of becoming musicians themselves (via Far Out). As Sumner recalled in "This Searing Light, the Sun and Everything Else," one of the main reasons for their inspiration was that the Sex Pistols sounded raw. "I thought they destroyed the myth of being a pop star," he mused. Curiously, the two men didn't have any musical training, so they swiftly picked up two books: "How to Play the Guitar" for Sumner and "How to Play the Bass" for Hook.

The men played some early shows, later adding Ian Curtis into the mix, and by May 1977, they landed a gig under the name Warsaw, opening for the Buzzcocks at Manchester's Electric Circus. Per Record Collector magazine, Warsaw didn't blow the audience away with their performance. As Buzzcocks manager Richard Boon recalled, "They weren't very good, but you could see that they were striving to get somewhere." Nevertheless, the musicians were ambitious and enthusiastic.

After changing their name to Joy Division after about six months, the band soldiered on with live shows, yet things weren't looking up just yet. According to RadioX, they had their very first London show in December 1978 — yet played to a tiny crowd. Curtis, who was fed up, took his frustration out on his bandmates, getting so upset that it resulted in his very first epileptic fit.

Ian Curtis struggled with epilepsy

Ian Curtis experienced his first epileptic fit in December 1978, in a car with his bandmates, en route back home from a show they played in London. According to Record Collector magazine, this was a grand mal seizure, which the Mayo Clinic describes as "a loss of consciousness and violent muscle contractions." He was officially diagnosed the following month, in 1979, per The Quietus.

"He didn't have epilepsy when the band started," Bernard Sumner recalled to Record Collector, noting that the band believed it was a passing diagnosis. "We didn't know what to do and didn't know much about epilepsy then. We were 20-year-olds," he added. Of course, Curtis' lifestyle must have contributed to his condition, with the late-night cocktail of performing shows complete with loud music, flashing lights, lack of sleep, and copious amounts of booze.

Curiously enough, according to The Quietus, Joy Division's manager, Rob Gretton, claimed that no strobes were ever used on stage, yet it's difficult to say if that rang true before his diagnosis. Whatever the case, Curtis' bandmates knew of his fragility and, after his first seizure, wholly embraced their new supporting roles in the band. As Peter Hook declared, "Looking after Ian became second nature really, it was just something we did all the time." For a while, it seemed like Curtis had a handle on his condition, and as Hook revealed to NME, during the recording of their first album, "Unknown Pleasures," the frontman managed to keep his epilepsy at bay.

Ian Curtis' bandmates believed his epilepsy medication contributed to his depression

The tale of Joy Division is tremendously heartbreaking, largely due to Ian Curtis' death by suicide on May 18, 1980 (via Independent). Looking back now, many fans have discussed the melancholy lyrics of the frontman's music catalog, yet it's something that bothers the remaining Joy Division members. "The one thing that really upsets me about the general perception of Joy Division and Ian particularly is that he always comes across as a morose, depressed individual," declared Stephen Morris to the Independent, adding, "He was anything but. We joined a band to have fun and that was what we were doing." The biggest problem, however, was that Curtis was known to hide his emotions from his bandmates, as Peter Hook explained in an article penned for The Guardian in 2011. According to Hook, the frontman never shared what he was truly going through, instead choosing to brush his problems under the rug.

After Curtis was put on medication for his epilepsy diagnosis in 1979, his bandmates noticed a change in behavior, with Morris telling the Independent he'd prefer to spend time by himself and was exhausted after playing gigs. Shockingly enough, as Hook revealed to WNYC in 2013, a present-day epilepsy specialist analyzed Curtis' medication and was stunned at how dangerous the pills were. "It was that strong ... the mixers of uppers and downers ... It was terrible," recalled Hook.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Their infamous Derby Hall gig in Bury resulted in a riot

Nearing the end of Ian Curtis' life, he sadly made two suicide attempts, the second being an overdose of barbiturates on April 6, 1980, per The Quietus. As Peter Hook wrote in The Guardian decades later, immediately after being released from the hospital, the Joy Division frontman was brought to band practice by Factory Records owner Tony Wilson himself. Asked by the rest of the group if he was okay, Curtis brushed off the incident and decided to keep busy with work.

A mere two days later, Joy Division was due to play a gig at Derby Hall in Bury, England. According to Hook, Curtis initially said he couldn't play but was inevitably brought to the concert anyway. After playing a couple of songs, the singer stepped off stage, and the band, panicked, asked Alan Hempsall of Crispy Ambulance to help out (via The Quietus). As Hempsall took the stage and began singing, the audience rioted. Hook attempted to fight the crowd while Wilson tried to restrain the bassist. Guitarist Bernard Sumner, on the other hand, stepped back. "Bernard's got his feet up on the table going, 'I hate violence, it's all so temporary,'" remembered Hempsall to The Quietus.

The 2007 Joy Division biopic "Control" famously immortalized the Derby Hall concert. Curtis' real-life daughter, Natalie, played an extra in the crowd, yelling at the on-screen Hempsall to get off the stage (via The Guardian).

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Ian Curtis had a short and unhappy marriage

Ian and Deborah Curtis married in 1975, at the young age of 19, per the Independent. Having both come from working-class families, Ian snagged a civil service job working at a local job center. These first few years of their marriage, as Deborah recalled in her biography, "Touching from a Distance," were glum. Although the young couple was in love, they loathed their jobs, and a monotonous daily routine led to bouts of depression. "It didn't take long to realize that married life was not going to be as comfortable as we had expected," Deborah wrote.

By 1979, Deborah gave birth to the couple's only child, Natalie. Interestingly enough, although Ian was a part of Joy Division at this point and close to his bandmates, he refrained from telling them about his wife's pregnancy early on — something that Deborah wanted to shout from the rooftops. She recalled Peter Hook discussing the band's issues years later, explaining that they "kept their relationships at arm's length and so did not share any happiness" (via "Touching from a Distance").

But Ian also had another secret, albeit not one he hid very well. The same year his wife gave birth, the singer also began his alleged affair with the late Annik Honoré, a Belgian journalist he met at one of Joy Division's concerts, per Independent. However, Honoré painted a different tale while speaking to Focus VIF in 2010, claiming that the pair had a "completely pure and platonic relationship."

Joy Division barely made any money in the short time they were active

Joy Division never came from privilege, making their impact on the music scene that much more inspiring. As Bernard Sumner once recalled, those who grew up in Manchester "didn't have much chance of progressing in the [world], really" (via New Internationalist). Moreover, the men always seemed to put their music first — no matter the price tag.

"Genetic Records were offering us a deal. It was £70,000," explained Peter Hook to NME about choosing to sign with Factory Records for their first album. Although the musicians were excited, their manager, Rob Gretton, talked them out of making a deal with a big-name London studio for fear of selling out. "We could be as awkward as we liked and we didn't have to sell as many records as Siouxsie And The Banshees or even the Sex Pistols to make a living," noted Hook.

"Unknown Pleasures" was officially released in June 1979, yet it didn't do much to change the band's financial status — although it did mean they finally quit their day jobs. In a separate interview with The Quietus, Hook quipped that their new "professional" gig paid "three quid a day." By the time Ian Curtis died the following year — and right at the cusp of an American tour — Joy Division was still dirt poor, unable to eat proper meals or even snag a drink at the local pub (via The Guardian).

Ian Curtis died right before they embarked on their US tour

Joy Division was never a world-renowned band in the short time they were active. In fact, as Peter Hook told the Independent, the last show they ever played in Birmingham only drew a crowd of 150 people. Nevertheless, Ian Curtis always believed that their sound would eventually have a global reach. "He'd always say, 'Don't worry, we are going to be big in Brazil. We're going to be big here, we're going to be big there,'" recalled Hook.

The frontman was right, although the band's success came by way of a tremendous tragedy. On May 18, 1980, Curtis died by suicide — a mere day before the men were due to embark on their first American tour. "On Sunday morning, I was turning my trousers up. Monday, I was screaming," remembered Stephen Morris to Rolling Stone. The months leading up to Curtis' death were troubling, with the singer already attempting suicide twice prior, yet it was the lackluster Birmingham show that was the final disappointment (via The Guardian).

As Hook told The Guardian, the remaining members of Joy Division were, understandably, in a state of shock. Not knowing what to do, they attended Curtis' funeral, and as they left, they merely told one another, "See you at practice."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The bootlegged merchandise fiasco

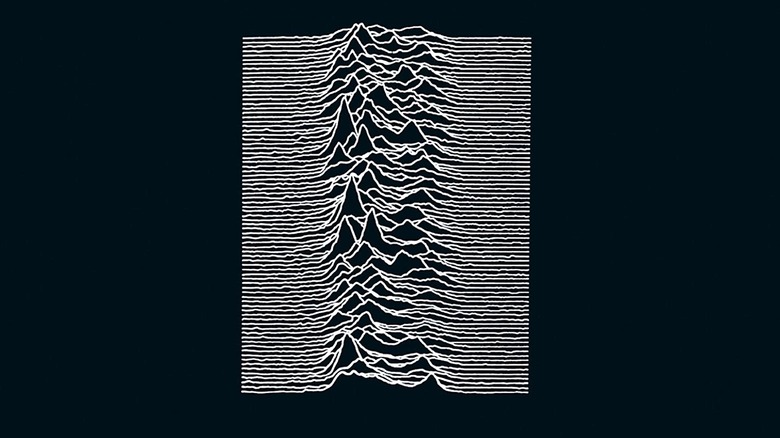

The cover art for Joy Division's first album, "Unknown Pleasures," is instantly recognizable. The credited creator of the cover is graphic designer Peter Saville, yet, according to the band, it's a bit more complicated than that. As Peter Hook told NME, "The only contribution Saville had was the typeface and the texture of the cover. And he's been dining off it for 30 years!" So, who was responsible for discovering the image? According to Maxim, that honor goes to guitarist Bernard Sumner, who found the artwork at the Manchester Central Library after flipping through an astronomy encyclopedia.

Unfortunately, the mishap with Saville and Sumner wouldn't be the only design fiasco Joy Division went through. These days, the iconic "Unknown Pleasures" cover has been copied on countless pieces of merchandise, from shirts, pillows, phone cases, and blankets — the list goes on. But as Hook told NME, the band never actually had merch and especially didn't have any "Unknown Pleasures" shirts — until 1994. Yet, because they were bootlegged globally, the band was fined taxes for not declaring any profits on the mass-produced tees.

In 2019, the band did release an official collection of various pieces of merchandise in honor of their debut album's 40th anniversary (via RadioX). That same year, they also handed out 40 free "Unknown Pleasures" shirts in Manchester, with the option of donating money to the charities Calm Zone and Big Change MCR, both chosen by Joy Division themselves and Ian Curtis' family, per NME.

The remaining Joy Division members formed New Order, with one promise

With Ian Curtis' sudden death in May 1980, the remaining Joy Division members were left in limbo (via Rolling Stone). As Stephen Morris recalled in his biography, "Record Play Pause," the idea of returning to regular nine-to-five jobs wasn't an option, so the men met at a local pub, and got to brainstorming a new name for the group.

According to RadioX, even before Curtis' passing, the band promised to stop performing as Joy Division if anything ever happened to any of the members. "Joy Division doesn't exist anymore, and it would be foolish to kid people into believing it does," declared Morris to Rolling Stone in 1983. And so, Bernard Sumner (who took over as vocalist), Peter Hook, and Morris created New Order, adding Gillian Gilbert as a keyboardist (via RadioX). Per The Guardian, Hook left the band in 2007, forming The Light. As he told the Independent, 30 years after Curtis' death, he's finally decided to perform Joy Division songs with his new band.

As for New Order, the group has left its own impact on music — perhaps just as much as Joy Division. As Splice Today writes, they're considered innovators of a unique blend of rock and electronic dance, with hits such as "Blue Monday" still resonating with the public today.