The Untold Truth Of The Kingdom Of Dahomey

Africa is often discussed in the West as if the entire continent was homogenous, whether the discussion is on current events or distant history. This is no more accurate or useful than treating Europe or South Asia or South America as a single entity. As historian Ana Lucia Araujo of Howard University has noted on her blog "A Historian's Views," the people of Africa, like all people, long identified by state, language, religion, and ruler over landmass. It's important to remember that, says Araujo, when considering the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.

Per UNESCO, the 16th and 17th centuries saw trading posts on the West African coast devote greater resources to providing slave labor to the Americas and the Caribbean. Kingdoms and nations along the coast condemned their enemies, prisoners taken in war or victims of raids, to lives of servitude in exchange for New World goods. The wealth and power the slave trade brought only encouraged rivals to pursue it, and to displace one another. Coastal kings would send envoys to European powers, lobbying for better trading terms and for the perpetuation of the slave trade.

By the mid-1700s, one kingdom had achieved a near-monopoly on the Bight of Benin, the most important hub of the slave trade: the kingdom of Dahomey. It remained one of the most important powers in the region until the end of the 19th century, and it claimed some of the most unique institutions.

Its origins are tinged with myth

Just how and when Dahomey emerged as a distinct, organized kingdom is unclear. Records of its early history are sparse, and various folkloric traditions have provided founding myths. According to Black History Month U.K., the majority of these myths were likely embellished, if not created out of whole cloth, to shore up the legitimacy of the monarchy in the 18th century.

The most popular of these myths paints Dahomey as a state born of conflict between three brothers. Descendents of Agassu, ruler of Allada, the brothers' feud ended with one enthroned in Allada and the other two exiled (per Britannica). One of them, Do-Aklin, journeyed to the Abomey Plateau and established a kingdom there of the same name, by permission of the local chiefs. When his son Dakodonu requested more land, one chief dismissively asked, "Should I open up my belly and build you a house in it?" Dakodonu killed the chief, marked the spot, and decreed his palace would be built there, the foundation of Dahomey.

The truth was probably not nearly so romantic. Finn Guglestad wrote in "Slave Traders by Invitation: West Africa's Slave Coast in the Precolonial Era" (via Oxford Academic) that Dahomey was likely established in the mid-1600s. According to Guglestad, its likely founders were outlaws who subjugated and killed the indigenous Guedevi people, in violation of traditional custom. Claiming descent from Agassu royalty would have dressed their conquest in a more respectable guise.

Driven by scarcity to conquest

The Abomey Plateau is not the most fertile of territory. As the population of Dahomey increased, its territory couldn't supply enough resources to sustain it. This, according to Elizabeth M. Halcrow's "Canes and Chains: A Study of Sugar and Slavery," was part of what fueled the kingdom's wars to extend their reach. What people lived between the plateau and the Atlantic were disorganized, while the Dahomeans were led by Wegbaja (Houegbadja), often counted by tradition to be the first true king of Dahomey according to Black History Month U.K.

It was under Wegbaja that Dahomey first went by that name. He instituted significant legal reforms and was allegedly prepared to execute his own children if they violated the law. Wegbaja's laws included protections for prisoners against harm until sentenced, and he sought to integrate tribes that his forefathers had conquered by honoring their chiefs with gifts and demonstrations. The military was also transformed under his reign, armed with guns rather than bows and subject to regular training in strategy.

But Wegbaja's strengthening of the state also saw the monarchy acquire despotic authority. He encouraged a cult of personality that positioned kings as both temporal and religious leaders of Dahomey. His taxes and confiscation of property from deceased subjects greatly enriched the crown at others' expense. And it was Wegbaja who purportedly began the "Annual Customs," an elaborate combination of great shows of state generosity with violent sacrifice.

Dahomey and Oyo

By the time Dahomey emerged in the 1600s, another state was firmly ensconced as the power in the region. The Oyo Empire had existed since the 1300s, according to Slavery and Remembrance, in what is now Nigeria. Predominately made of Yoruba people, the Oyo Empire benefited from its location north of the range of the tsetse fly. This allowed its warriors to breed horses and maintain an armored cavalry, which in turn let them reach as far as the Bight of Benin when making war.

Dahomey maintained a mutual antagonism with the Yoruba (per Britannica). As the slave trade developed, neighboring Yoruba kingdoms were raided by Dahomey for stock. But the power of Oyo could not be assailed, and by the 1700s, Dahomey was one of many states made a vassal of the empire, according to "A History of the African People." While it kept its king, its autonomy within its borders, and its regional influence, Dahomey was obligated to pay Oyo regular tribute.

But the Oyo Empire didn't hold all the cards in this contest. Located in the Bight of Benin, Dahomey was among the most influential mediators between European ships and African states further inland. Like Dahomey, Oyo had a considerable stake in the slave trade. As Dahomey's wealth and territory increased over the 18th and 19th centuries, the two powers came into conflict as Oyo sought to maintain a direct line to the coast.

War over Allada

Under King Wegbaja, Dahomey became an efficient and organized state, well-positioned to make war on its neighbors. The policies that made it so continued under Wegbaja's sons, Akaba and Agaja. Akaba pushed as far as the natural borders around the Abomey Plateau allowed, per "Canes and Chains." But to push as far as the Atlantic would mean conquering the kingdoms of Allada and Whydah, two coastal states heavily involved with various European powers in trade (per Black History Month U.K.). Both were major suppliers of enslaved people, and Allada was aligned with the Oyo Empire further inland.

Akaba ceded this dilemma to his younger brother, Agaja. Like his father, Agaja was a charismatic ruler who combined generosity and ruthless authority, and he furthered Wegbaja's military reforms with military academies and an intelligence-slash-propaganda ministry known as the Agbadjigbeto. And in 1720, he led his army on a march to claim the coast.

Some (per the BBC) have suggested that Agaja opposed the slave trade, and that such opposition helped motivate his aggression. Others hold that, while Agaja may have wanted to stop raids on his own people, he was more interested in enjoying direct trade with Europe — enslaved people included (per "Wives of the Leopard"). Whatever his motives, Agaja conquered his rival kingdoms by 1724 and engaged Oyo two years later (per Britannica), a war that ended with Dahomey as a vassal but with its newly-won territory intact.

The power of the Slave Coast

The scale of the transatlantic slave trade is sobering. Per UNESCO, millions of human beings were carried out of Africa to lives of enslavement in the New World, just out of the Bight of Benin. The British, French, Danish, Portuguese, and Dutch who traded in West Africa dubbed that region the Slave Coast.

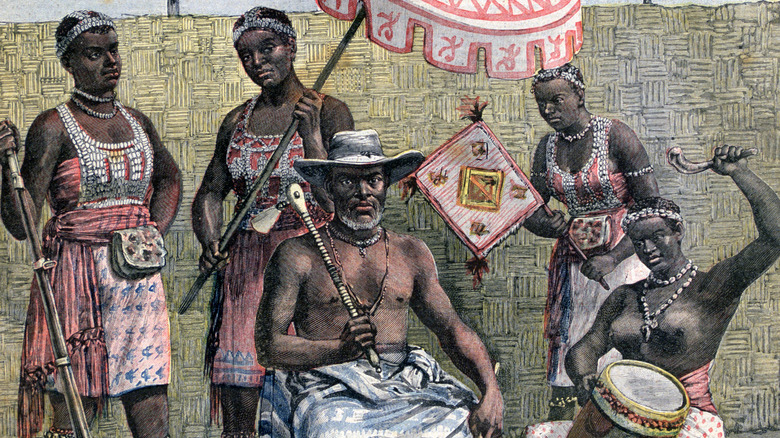

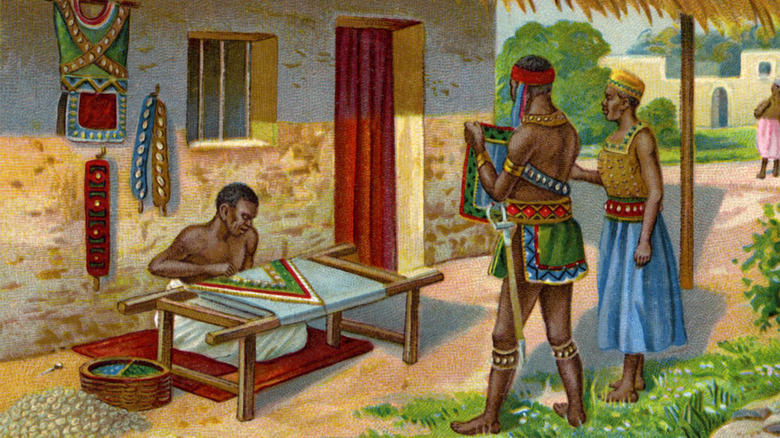

Dahomey's stake in the slave trade increased significantly after it monopolized control over the main trading routes on the coast. According to Black History Month U.K., by the end of the 1700s, Dahomey was responsible for up to 20% of the slaves traded to Europeans, even under pressure from the Oyo Empire to limit its involvement (so as not to undercut Oyo's own business in the slave trade). For their human cargo, the Dahomeans received firearms and powder, liquors and tobacco, fabrics, and cowrie shells. In negotiating with European powers, some kings of Dahomey were candid in valuing such items so that they could impress and awe their subjects and courtiers (per Ana Lucia Araujo of Howard University at A Historian's Views).

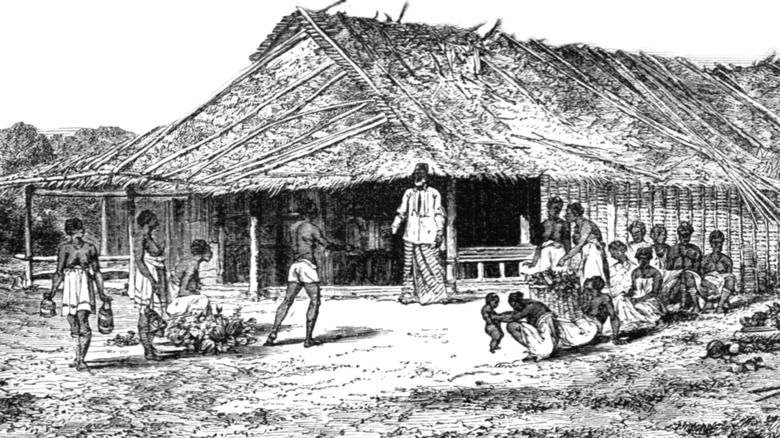

The desire for European goods fueled the raids and wars that brought Dahomey its stock, but not everyone captured by them was sent across the Atlantic. Slavery was practiced at home, too. Per Britannica, Dahomey maintained large plantations to feed the army and the royal court, and these were worked by enslaved people.

Religion and politics opened doors for women

The traditional religion of Dahomey was the many-branched Vodun, colloquially known as voodoo (per the Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library). The form practiced in Dahomey posited an androgynous creator-god called Nana Buluku, beyond human comprehension and the fount from which all life and sprit emerge. The dual nature of this high figure in the native religion was reflected in a two-tier system in Dahomey's civic life.

According to the BBC, every religious, political, and military institution in Dahomey was split into male and female offices. For example, the combined role of prime minister and executioner, the male migan, was offset by the female nae-miganon, according to Professor Boniface Obichere in the Outre-mers. Revue d'Historie. These female officers acted as a check on their counterparts and answered directly to the king, according to Britannica. There may have been a role for women on the throne at one time; oral histories and legends describe a Queen Hangbe, sister to Akaba and Agaja, whose legacy was erased by the latter when he deposed her. But there is some question among historians whether Hangbe ever existed.

Whether Hangbe lived and reigned or not, for all practical purposes, women below the crown were equal to men in Dahomey. If they had wealth and status, women could hold their own lands, operate their own businesses, wield political power in their own right, and buy, sell, and execute their own slaves.

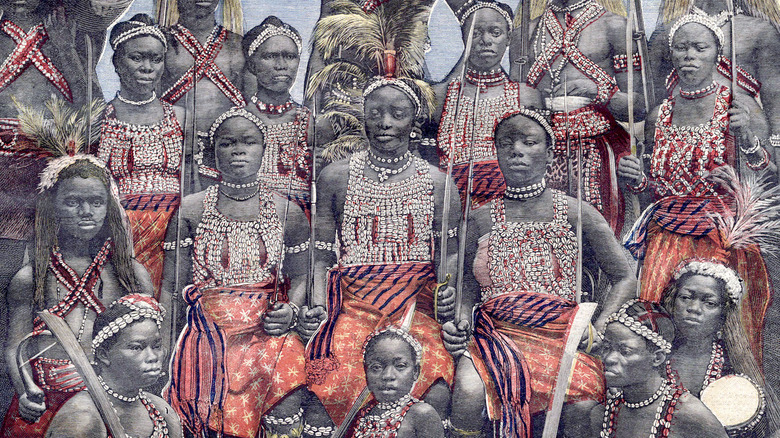

The Dahomey Amazons

Probably Dahomey's best-known aspect is its all-female military units, known to the West as the Dahomey Amazons. Known as mino in the Fon language, the origins of these fighting forces are uncertain. One tradition, according to the BBC, holds that they were the brainchild of Queen Hangbe in the early 1700s. In other tellings, such as that reported in "Canes and Chains," King Agaja created the corps. In still another, the mino were elephant hunters who became royal bodyguards with time.

Whatever their origin, the mino were unique for their age in history. Women in other times and places had donned armor and ruled nations, and King Mongkut of Siam kept a ceremonial female bodyguard around him (per Smithsonian Magazine). But the mino were an active fighting force. Trained from childhood, drilled in marksmanship and swordplay, subjected to "insensitivity training" that involved throwing prisoners into angry mobs, they took and inflicted heavy casualties in Dahomey's wars. Initially numbering in the hundreds, King Ghezo expanded the mino to 6,000 in the 1800s and integrated them into the larger army.

As warriors, the mino achieved international fame. But away from the battlefield, they still had a significant role to play in daily life. They exercised influence in their villages and could exercise authority independent of local chiefs. Some were also protectors and caretakers for hungry children (per the Washington Post).

The Annual Customs

Dahomey was a highly centralized state. Per Britannica, peoples conquered by Dahomey were made to assimilate through imposition of Dahomean law and intermarriage. A cult of personality was encouraged around the reigning sovereign and the monarchy itself. As an absolute monarch, the king of Dahomey was seen as vital to the life of the nation. Ancestor worship was a key component of Dahomey society, particularly the reverence of deceased kings.

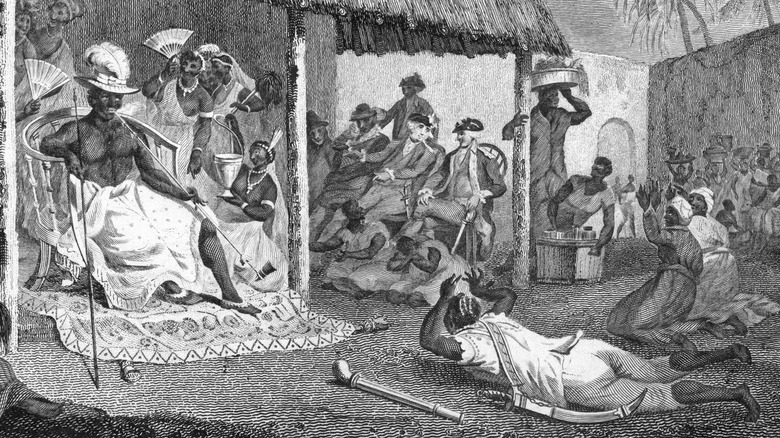

The Annual Customs commemorated departed rulers and the living court. According to "Canes and Chains," they began under King Wegbaja in the 1600s. During the ceremonies, ministers, merchants, nobility, provincial governors, and village chiefs would all bring gifts to the king (pe Edna G. Bay's "Wives of the Leopard"). The king in turn would shower gifts on those who paid him tribute, including the heads of subjugated peoples. The king represented his ancestors in one sense, but the exchange was also a ceremonial renewal of the social contract: Subjects accepted and empowered the ruler, and the ruler protected and provided for the subjects. Regional disputes could also be debated and adjudicated during the Customs.

Such ceremonies were common in Africa, according to Professor Wallace Mills of Saint Mary's University. What made Dahomey's Customs so notorious was the sacrifice of dozens to hundreds of prisoners and enslaved people to honor former kings. If generosity and reverence didn't impress subjects and rivals, noted "A History of the African People," shows of terror might.

Triumph and decline under King Ghezo

Major shifts came to West Africa in the 1800s. Dahomey reached the height of its power. Under King Ghezo, who reigned from 1818 to 1858 according to Black History Month U.K., successful military campaigns freed Dahomey from its vassal status to the crumbling Oyo Empire. Besides his martial prowess, Ghezo was also a reformer. His reign saw improvements to the government bureaucracy and a new commitment to the arts (per Britannica).

But Ghezo's reign also saw the beginning of Dahomey's decline. Britain's shift from slave traders to abolitionists in the 1830s led to increased pressure on Slave Coast states to end the trade. Ghezo responded that he would accommodate the British on anything else, but on this, he said, "The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth" (per the BBC). The British answered with a blockade in 1851, while the haven city of Abeokuta won victories in a war against Dahomey, the slavers they sought to escape.

Ghezo accepted a treaty ending the slave trade in 1852. To replace the lost income, he shifted Dahomey's primary export to palm oil, grown in fields still worked by enslaved people (the British made no fuss about domestic slavery). But it was a far less lucrative enterprise. The economy faltered, the court split into rival factions, and Ghezo was assassinated in 1858. The assassin was connected to Abeokuta, setting off another war that the haven city won.

The fall to France

Situated on the west coast, in control of vital trading ports, Dahomey was a tempting prize during Europe's infamous Scramble for Africa. France had established factories and forts in West African territory as far back as 1670, according to Britannica, but abandoned them well before Dahomey claimed the coast. But in 1842, the French reoccupied their old fortress at Ouidah to establish a headquarters for the palm oil trade that was supplanting slave exports. In the following decades, Dahomey conceded several cities to France as protectorates under King Ghezo and King Glele (per Black History Month U.K.).

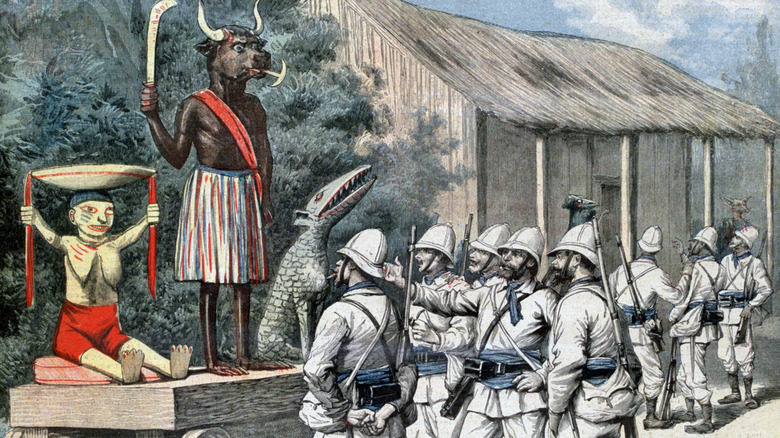

The concessions ended with King Béhanzin in 1889. He renounced prior treaties with France and launched slave raids into French protectorates, setting off the Franco-Dahomean War in 1892. The conflict saw the final battles of the mino, the Dahomey Amazons, in November of that year. The French who defeated them acknowledged them as formidable and honorable opponents (per Smithsonian Magazine), but in the aftermath of the war, records of their history and the opportunity they represented for women were suppressed (per the Washington Post).

The French could suppress such history thanks to their victory in 1894, making Dahomey a French protectorate. The capital of Abomey and King Béhanzin were captured. The king was exiled to the French Caribbean and the presumably pliable Agoli-Agbo was installed as a puppet ruler. When Agoli-Agbo opposed a poll tax, France deposed and exiled him as well and dispensed with the monarchy.