Lies You Learned In History Class

History has a funny way of repeating itself, especially when the people repeating it aren't exactly telling the full story. Indeed, many of the clean, easy, wholesome "facts" you learned in history class would earn you a big fat F in the decades-long class that is Real Life.

Here are a few historical lies that will make you rethink your entire education.

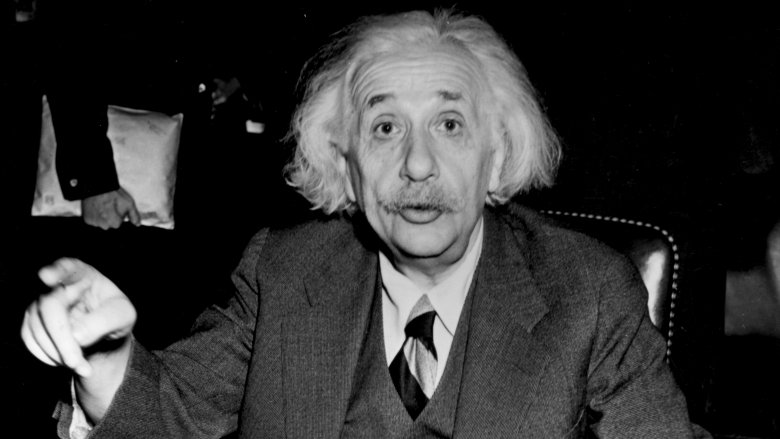

MYTH: Einstein failed math

For decades, teachers and parents have tried to inspire kids who didn't quite excel in school with a historical fun fact: "Even Einstein failed math as a kid." It's meant to encourage students to work harder or to imply that it's fine to be a late bloomer. It's a great message, but it isn't based in reality. Albert Einstein, the man who developed the theory of relativity and whose name also means "genius" (seriously, what are the odds?) didn't fail math. Why do people believe this?

In 1984, a Princeton University team led by John Stachel prepared to publish Einstein's papers. The group found evidence that Einstein was a kid genius who had conquered college-level physics by age 11 and was fluent in Latin and Greek. Stachel also found what he thought was the source of the Einstein math myth. Stachel told The New York Times that when Einstein was 16 and studying in Switzerland, he received grades of "1" in math on two straight report cards. On a scale of 1 to 6, "1" was the best. But then the school switched its system so that a "6" was the top grade given. At that point, Einstein got a "6," which made it look like he was suddenly flunking math. He wasn't — he was still getting the equivalent of an A.

Was Einstein actually bad at any subjects? Just French. French is hard.

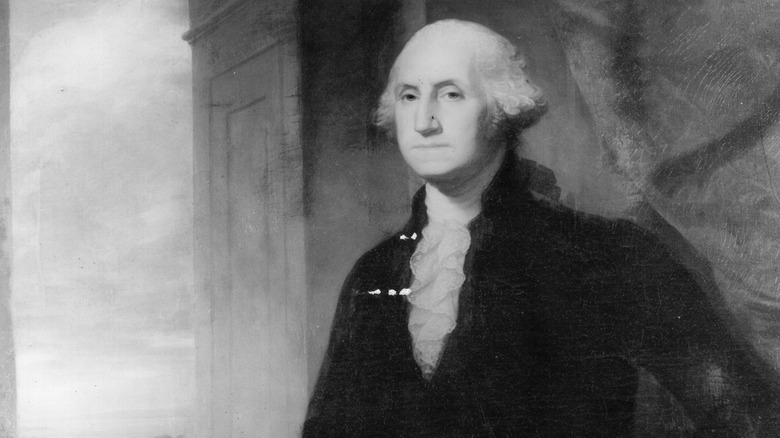

MYTH: George Washington chopped down that cherry tree

For decades, it seemed like every American classroom couldn't get through the Revolutionary War without teaching the story about how America's first president, George Washington, famously confessed to chopping down his father's cherry tree when he was just 6 years old. "I cannot tell a lie," allegedly said little G. W. Well, as it turns out, that story was itself a lie. Oh, the irony.

The story has become such an infamous myth over the years that even the official website of the home of Washington, Mount Vernon, has squashed it once and for all, claiming the whole thing was made up by Washington biographer Mason Locke Weems in 1806. Among his alleged reasons for lying, according to the website: profits, the desire to look at Washington's private life, and the need to "present Washington as the perfect role model, especially for young Americans." Whatever the reason, the myth worked for centuries.

MYTH: Feminists burned lots of bras

When classrooms gloss through the Women's Liberation Movement, one of the topics that almost always gets brought up is the movement's protest of the 1968 Miss America pageant, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. According to history, we were told that a bunch of protesters at the event took off their bras and immediately set fire to them. Well, according to Carol Hanisch, one of the organizers of the protest, that's not exactly what went down.

Truth be told: The women did want to burn their bras; Hanisch admitted that much to NPR in an interview 30 years after the protest took place. But because police wouldn't let them do that on a boardwalk, they were forced to throw a bunch of "instruments of female torture" like bras, girdles, and Playboy magazines into a garbage can. It was inside that garbage in which the fire was ultimately lit. "The media picked up on the bra part," Hanisch told NPR, dispelling the "bra-burning" myth once and for all. "I often say that if they had called us 'girdle burners,' every woman in America would have run to join us."

MYTH: Pilgrims dressed in black and white

Learning about the Pilgrims and their role in the European colonization of America is a major part of any American's elementary school education. Also a part of school: school plays in which kids dress up like Pilgrims and re-enact the first Thanksgiving. Invariably, the costumes are ill-fitting black and white garments topped with big, black hats. It's reasonable to assume the Pilgrims dressed that way — simple, demure clothes for simple, demure people. However, according to Pilgrim expert Caleb Johnson, the Pilgrims wore clothes that were all kinds of styles and colors.

The notion that Pilgrims dressed like they were colorblind came much later. Artists like Michael Felice Corne produced paintings about the Pilgrims in the early 1800s, according to the LA Times. Corne and others didn't really know what the Pilgrims would have worn, so they depicted them in clothing more modern and familiar — particularly all that black-and-white stuff.

MYTH: Slavery was just in the South

Though school taught us something different, Southerners didn't get a patent on racism, and people of the North have a bad history of slavery.

The colonial North thrived on the slave trade in the 1700s. During the Revolution, George Washington told Northern and Southern colonists that we must fight the British so we don't become "as tame and abject slaves as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway" (via the New York Historical Society). By 1804, slavery was abolished in the North, but not all at once. Some states left in provisions to slowly free slaves over time, and by 1840, Connecticut still had 17 slaves listed on the census.

In New York City, the situation was especially shameful. A fifth of the city's population was slaves in 1740, and New York had the second-highest rate of slave ownership in the country (42% of residents owned slaves, according to the New York Public Library) behind only Charleston, South Carolina. Slave labor built much of the city, and although they didn't have to work on plantations, "You are still considered property to be bought, sold, and used" isn't much consolation.

Even during the Civil War, New York City came close to joining the secession after South Carolina. Though the city wanted to side with the South mostly for economic reasons, they still weren't worried about the idea of siding with slaveholders. The New York Herald wrote, "If Lincoln is elected, you will have to compete with the labor of four million emancipated negroes." So, if a Yankee guy gets a little high and mighty around his Southern friends, just remind him of that quote and watch his liberal guilt consume him.

MYTH: Napoleon was really short

One of the best — okay, funniest — parts about studying the French Revolution in social studies class was finding out that the famous French military leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, was actually super-short in height. Just how short, you ask? Well, according to teachers all over the country, Napoleon stood a measly 5'2". Granted, his alleged height didn't stop him from kicking ass during the war; however, it did become infamous enough to create the term the "Napoleon complex," used to describe people who make up for their short height by being totally strong and aggressive, socially.

In any case, despite all of this, Napoleon's height has since been up for debate. According to the BBC, historians are now estimating that he was actually more along the lines of 5'6" — or, more to the point, one inch taller than former President of France Nicolas Sarkozy. What happened? The BBC claims the height might have gotten lost in translation between French and British measurements. Which, if you really think about it, is a Napoleon complex in of itself.

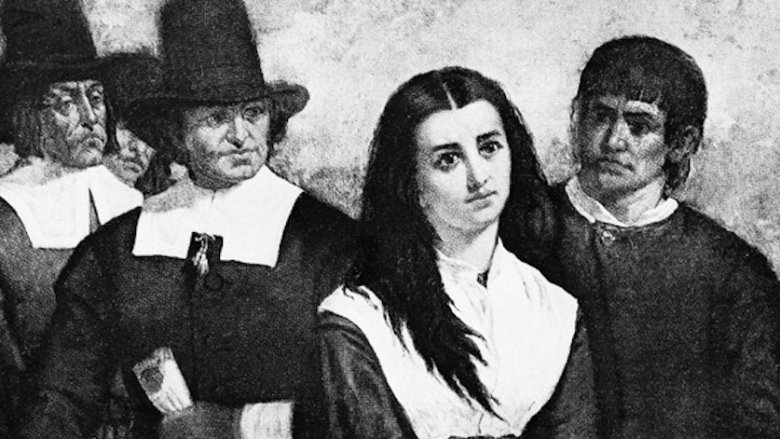

MYTH: Witches in Salem were burned at the stake

The Salem witch trials of 1692-93 remain one of the darkest chapters of American history. In the Massachusetts colony, more than 200 people were accused and tried for the difficult-to-prove "crime" of being witches. Twenty of the accused were found guilty and killed straightaway. However, none lost their lives by being burned at the stake like most people think. At least, none of the American witches did.

In European witch trials — they were all the rage — guilty witches were executed with fire. In Salem, 19 of the 20 witches were hanged on Gallows Hill. The other witch, Giles Corey, was crushed to death with heavy rocks.

MYTH: Paul Revere yelled, 'The British are coming!'

If your dusty old history books are to be believed, the build-up to the American Revolutionary War was pretty dramatic: A dude named Paul Revere rode through a bunch of towns on horseback screaming "The British are coming!" and everyone freaked out and got their guns and the war started the next day. As it turns out, that only sort of happened.

Revere was indeed ordered to Lexington, Massachusetts, to tell Samuel Adams and John Hancock that the British were coming. But the actual quote has since been misconstrued. According to the website for The Paul Revere House, a sentry at the house where Adams and Hancock were staying got all mad at Revere when he arrived because he was making too much noise. To which Revere replied dramatically: "Noise! You'll have noise long enough before. The regulars are coming out!" Sure, that may sound less like a movie moment and more like a bad regional theater production, but hey, facts are facts. And speaking of: The website goes on to say that Revere was joined by two additional riders, all of whom were arrested and released on their way to Concord. No word on whether they, too, had a catch phrase.

MYTH: Bastille Day celebrates freed prisoners and the French Revolution

While you're busy relaxing on a beach somewhere or nursing a hangover from a really epic Fourth of July party, you might notice somebody'll post about France on July 14. That's Bastille Day, a day of French Independence to mark the famous storming of the Bastille to free the unjustly imprisoned and start the revolution. Or so you think.

After King Louis XVI dragged the nation into poverty then tried to drastically raise taxes to cover his behind, the people of France weren't thrilled with his leadership. On July 14, 1789, the French had had enough and went on a quest to find guns and ammo to start fighting back. The Bastille was once full of political prisoners, but by 1789, the place was nearly empty with just a handful of prisoners left inside. When revolutionaries came to the Bastille doors, they weren't there to free prisoners. They showed up to get more gunpowder.

Since the freedom fighters were all riled up, their powder raid turned violent, and they killed and beheaded the prison officers while freeing the remaining inmates. So, the raid of the Bastille was really just a looting gone wrong. But it scared the crap out of the king, who agreed to compromise with the rebellion and end feudalism. Since the Bastille raid came at the right time, it turned from a tale about stealing gunpowder and going beheading happy into a tale of a fight against tyranny. So, when you're celebrating Bastille Day with your traditional baguette and inflated sense of superiority to honor France, remember you're really honoring a bunch of jerks who cut off some heads for pretty much no reason.

MYTH: Gandhi was nearly a saint

Picking on Gandhi seems like a pretty low blow or a decent name for an emo band. So, awful, either way. The idea that the mind behind the non-violent fight for India's independence could be anything less than pure seems almost heretical. In fact, Pulitzer prize–winning journalist Joseph Lelyveld's realistic biography of Gandhi has been banned in Gandhi's home state of Gujarat for blasphemy. But that doesn't make Lelyveld's words any less true.

Most of us don't know that Gandhi abandoned his wife to live with a rich male bodybuilder before he got involved in British-Indian relations. Now, if Gandhi was gay, who cares? But Gandhi tried to get all references to homosexual traditions erased from Indian temples in an act he called "sexual cleansing," as per the Huffington Post. And to test his resistance to sexual temptation, he'd sleep in bed naked with his teenage grand-nieces. But worse than his sexual hypocrisy was his terrible racism.

Gandhi may have wanted India freed from British rule, but he was perfectly happy with the rigid caste system of the nation. Gandhi wrote of a time when he and his followers were led to a lower-caste jail for protesting. "We could understand not being classed with whites, but to be placed on the same level as the Natives seemed too much to put up with. Kaffirs [the South African equivalent of the N-word] are as a rule uncivilized — the convicts even more so. They're troublesome, very dirty and live like animals" (via the Huffington Post). When asked about Indian views on race versus white South Africans, he wrote, "We believe as much in the purity of races as we think they do." Though Gandhi did bring some good to the world and was tragically assassinated, we also need to learn that he was only human—and a human with some truly abhorrent ideas.

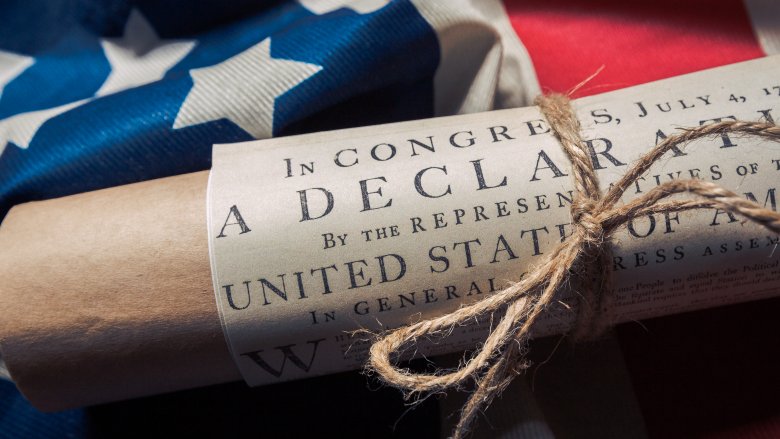

MYTH: The U.S. declared independence on the Fourth of July

Fireworks, flag cakes, and barbecues — your Fourth of July activities to celebrate American independence from Mother England are a lie. The Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia on July 1, 1776, and the next day — July 2 — representatives from the 13 colonies overwhelmingly approved a motion to declare independence. The assembly spent two days revising a statement primarily written by Virginia delegate Thomas Jefferson — the Declaration of Independence — and ratified it on July 4, ingraining "the Fourth of July" into the brains of freedom-loving Americans forever.

"Fine, it was ratified on July 4, big deal," you're saying. Wait a minute! The members of the Second Continental Congress still had to actually sign the Declaration of Independence, and they didn't start leaving their Herbie Hancocks until August 2, 1776. Because news traveled a lot slower in 1776, it took a while for King George III of England to hear about the Declaration. He made his first public remarks on the matter in October 1776.

MYTH: President Kennedy brought about Civil Rights Legislation

Without John F. Kennedy, we may never have had civil rights legislation, or so we've been taught. But Kennedy had little to do with civil rights laws. When he heard about the planned March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his "I Have a Dream" speech, Kennedy tried to stop it. He even sent vice president Lyndon B. Johnson to Norway during the march because he didn't like LBJ's pro–civil rights policies.

Kennedy was forced to act on civil rights after the Freedom Riders and the assassination of Medgar Evers, but he thought the legislation would never get through and would hurt his chances of passing the bills he really cared about. But after Kennedy was shot, LBJ put all his efforts as president behind the Civil Rights Act. Capitalizing on the fresh memory of the young president slain, LBJ used the people's grief and frustration to get Congress to act. And in the end, JFK got all the credit.

MYTH: Until feminism, women stayed home and men worked

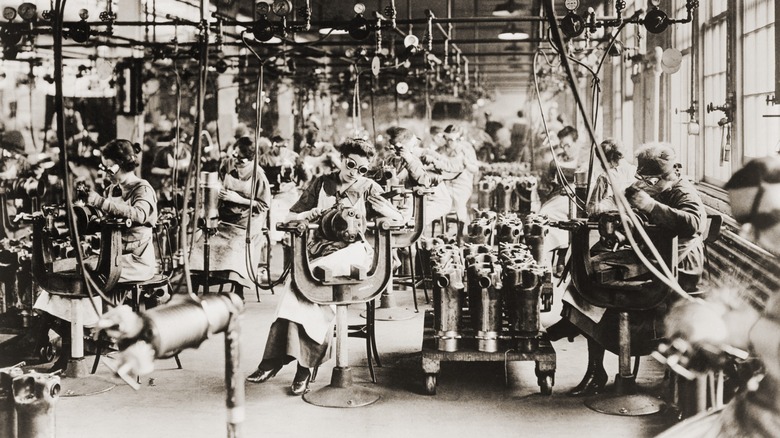

The minimal women's history you learn in school usually revolves around the idea that ladies always had to stay at home, then had to go to work in the factories during World War II, but went back home after the war until feminism came along. But this is far from the full picture. Yes, lots of women were housewives or mothers and not allowed or not encouraged to work after getting married. But that ignores the many other women who didn't have the privilege of not working. Plus, it hides decades of history where men and women worked equally.

Before the Industrial Revolution, work was an extension of the household, and tasks were split evenly between men and women. Even by the turn of the century, women held a quarter of industrial jobs and half of agrarian jobs. Factory work at the time was incredibly dangerous, and gendered labor laws reinforced the growing idea that men should earn the money and women should stay at home. Still, women of color didn't get that luxury. Even after marriage, many continued to work since their husbands were paid less and had poorer jobs. When white women started to see progress, women of color were usually left out of the conversation.

Even in the '50s, women workers weren't so rare. Look magazine often profiled female workers, and radio programs talked to "career girls" who felt women should be able to find meaning and purpose outside the home. Sure, the males on the panel thought she wasn't serious about having a career because she occasionally thought of falling in love, but we're not here to debunk the idea that '50s white guys had issues.

But the working girls got erased, making women seem like frail, put-upon creatures of history till they finally burned their bras and sang Helen Reddy songs.

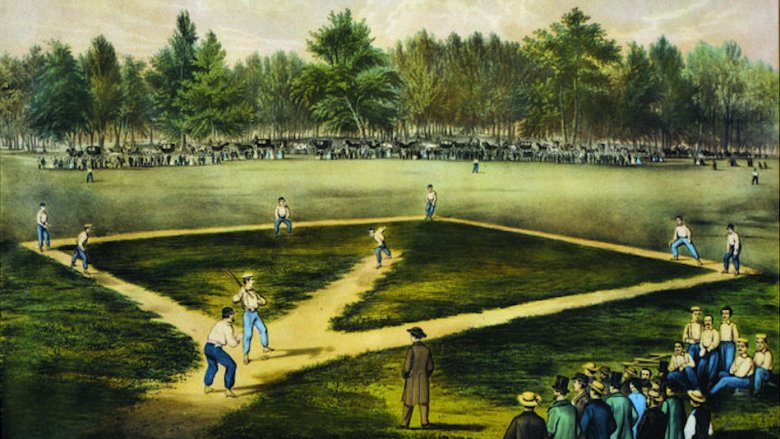

MYTH: Abner Doubleday invented baseball

In 1903, Baseball Guide editor Henry Chadwick wrote about how baseball had evolved from the British games of cricket and rounders. The magazine's publisher, sporting goods kingpin Albert Spalding, objected — baseball was American and simply had to have American origins, he said. He set out to prove it, forming a commission that asked the public for information about the game's early days. The commission's report, issued in 1907, was based mainly on a letter from a man named Abner Graves. He claimed to have been in Cooperstown, New York, in 1839 when future Civil War general Abner Doubleday outlined a diamond in the dirt and wrote up rules for a game called "Base Ball." Spalding took that for fact. To do so, he ignored two actual facts: that commission member A.G. Mills (who was close friends with Doubleday) couldn't remember Doubleday ever mentioning baseball and that in 1839 Doubleday was a cadet at West Point, not in Cooperstown.

In the mid-1930s, Major League Baseball made plans to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Doubleday's invention in 1839. That's when baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis got a letter from a man named Bruce Cartwright. He claimed his grandfather, Alexander Cartwright, invented baseball and that he could prove it with the original written rules, a field diagram, and a scorecard from the first game, played in Hoboken in 1845. The Hall of Fame honored Cartwright for his contributions, but Doubleday stayed in the public consciousness as baseball's creator.

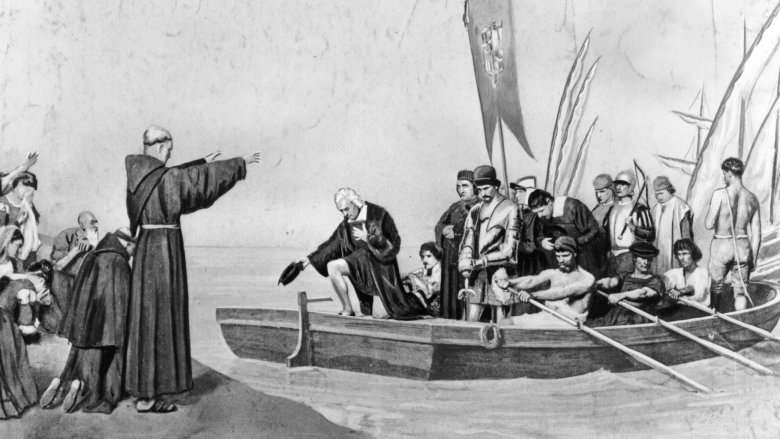

MYTH: Columbus needed to prove the world was round

While few still think Christopher Columbus discovered America, many believe the explorer's voyage was important because it proved the world was round. According to historian Jeffrey Burton Russell, the idea that Columbus had to prove a planet full of flat-Earthers wrong didn't take hold until the 1830s or so. French writer Antoine-Jean Letronne was so anti-religion that in books like "On the Cosmographical Ideas of the Church Fathers," he argued that Catholic Church leaders of the past foolishly believed the world was flat. Letronne's contemporary, Washington Irving, best known for "Rip Van Winkle" and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," published "A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus" in 1828. Irving primarily wrote fiction, and he used his storytelling skills to embellish his Columbus biography. In other words, he made stuff up, such as the passage in which Columbus tries to convince a council of 1490s religious clerics that he won't sail off the edge of the Earth.

People knew the Earth was round at least as far back as ancient Greece. Science historian Stephen Jay Gould wrote that the concept of a round earth was "central" to Aristotle's fourth-century B.C. writings on cosmology, as well as to Eratosthenes' calculating the Earth's circumference in the third-century B.C. Few people in Columbus' time were dumb enough to think the Earth was flat, but people in our time are dumb or snobby enough to think everyone else is dumb.

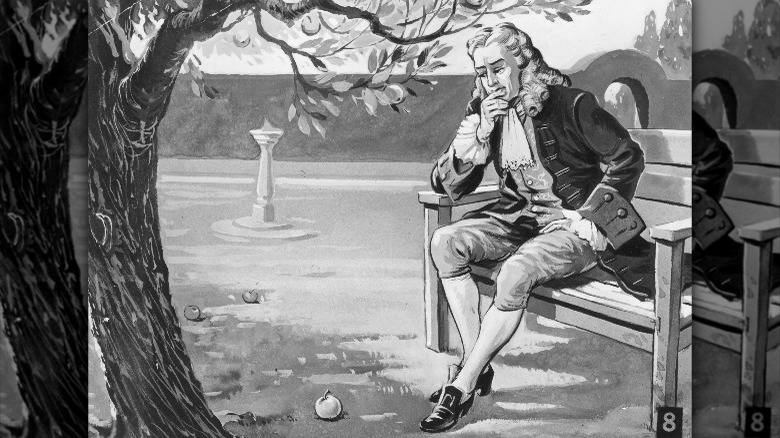

MYTH: An apple fell on Isaac Newton's head

When the history of Isaac Newton is taught, many teachers quote the old story that the physicist and mathematician actually came up with his theory for gravity after an apple fell from a tree he was sitting under and hit him smack on the head. You probably believed it in part because, duh, it's an old story and, duh, Newton was really smart. But, again, this story is only sort-of true.

While Newton did actually put two and two together by watching an apple fall, The Royal Society in London concluded in 2010 that the incident took place in his mother's garden and that there is "there is no evidence to suggest that it hit him on the head." That's a bit of a bummer. But, hey, he still came up with the theory of gravity, which is more than anyone reading this article can probably say.

MYTH: The 'War of the Worlds' broadcast caused mass hysteria

The textbook definition of "mass hysteria" is probably the October 1938 chaos that resulted from Orson Welles' radio adaptation of H.G. Wells' "The War of the Worlds." Welles and the "Mercury Theatre on the Air" radio program presented the terrifying story of a New Jersey alien invasion as breaking news, with on-the-scene reports so convincing that hordes fled their homes in terror. We know that happened because the newspapers of the day said so! Unfortunately, the creative license hadn't ended with the radio program. Newspaper publishers took what reports there were of panic — supposedly, 2,000 people called the Trenton, New Jersey, police department looking for information; New Jersey-based National Guard members tried to report for duty — and built it up to create a story of far-reaching mania over "War of the Worlds" and to make radio look bad. Gotta watch out for those emerging technologies.

In fact, relatively few people were "fooled" by "The War of the Worlds." Just in case anybody tuned in late, CBS Radio aired multiple disclaimers reassuring listeners that the broadcast was fictional. Also, there couldn't have been widespread panic because not very many people were even listening in the first place. Ratings reports from the time found that only 2% of respondents tuned in to "The War of the Worlds" – it aired opposite NBC's popular "Chase and Sanborn Hour." That show featured ventriloquist Edgar Bergen. Sure, 1930s Americans didn't believe aliens were landing, but they thought a ventriloquist they couldn't see was the height of entertainment.

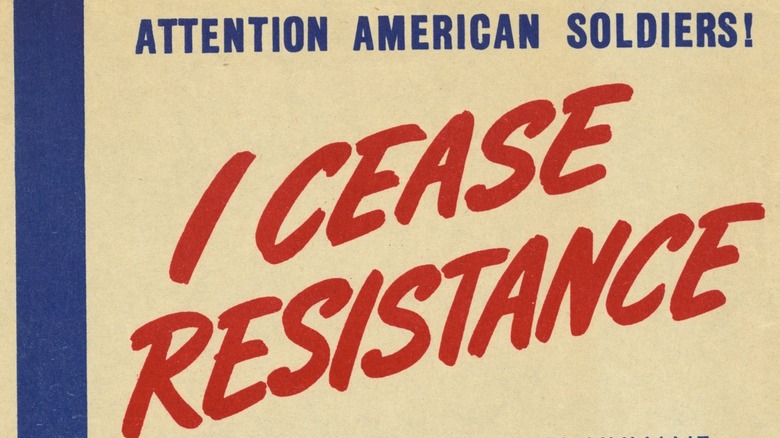

MYTH: America was enthusiastic to join World War II

Even the people who marched with "No blood for oil" signs and are currently protesting drone strikes tend to still have a little fondness for World War II. Who doesn't want to defeat a bunch of Nazis and get the chance to make fun of Germans? World War II was just too good to resist.

But Americans at the time weren't so enthusiastic. President Franklin Roosevelt was the most vocal supporter of the war, while oddly enough, aviator Charles Lindbergh was one of the biggest opponents. Lindbergh's strong isolationism got him labeled as a Nazi sympathizer. It's not exactly true, since he mostly admired Germany for their technology and economic revitalization. But he also thought white people were superior to everyone else, so honestly he was about as close to a Nazi sympathizer as you could be without donning a swastika. Lindbergh said he didn't approve of Hitler's treatment of Jews, but he seemed cool with everything else.

Other Americans wanted to stay out and weren't motivated by racism. Europe seemed like another world, and we had no place in their fight. Plus, the war meant the draft was coming back, and most people weren't interested in having a repeat of the Civil War or World War I.

College students were one of the largest contingents against the war. They figured they'd be the first to die if we headed overseas, so students at Yale formed a large isolationist group called "America First." Members of the group included Gerald Ford, Supreme Court Justice Potter "I know it when I see it" Stewart, Gore Vidal, and John F. Kennedy. It seems like young people always fought every war. If we could go back to the college campuses during the American Revolution, we'd probably see a lot of people with "No blood for tea" signs.

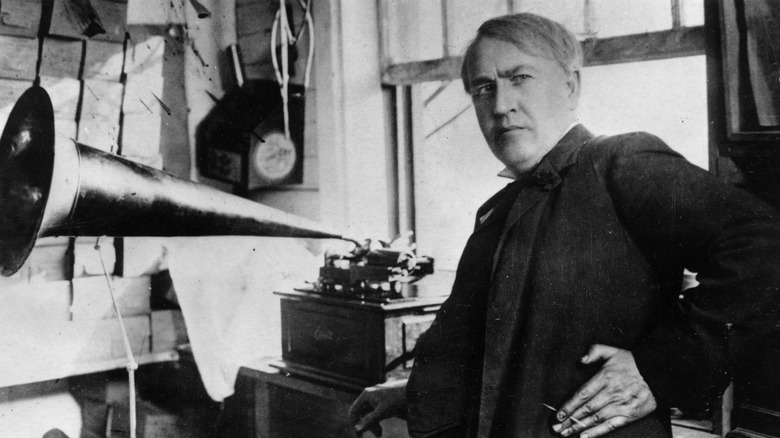

MYTH: Edison was a great inventor

In school, we learn that Thomas Edison was a great inventor who gave America the gift of light in bulb form. You can't deny that Edison was a bright mind who developed several things that made life easier for everybody. But you should also learn that Edison was a monopolizing, thieving jerk.

Firstly, he didn't really invent the lightbulb. He built upon several other inventions, and some say he stole several innovations that led him to creating and taking credit for the bulb we know today. Edison had a team of workers at his Menlo Park, New Jersey, facility, and in 1892, they invented the kinescope. It was the beginning of moving pictures, and while it may not sound entertaining now, the idea of moving pictures was pretty ingenious. Edison's assistants tried to get him to invest more time into inventing a projection device for this new technology, but Edison thought there was no money in moving pictures.

After kinescopes became incredibly popular, Edison did a 180 and started working on a projecting device. Or rather, Edison asked other people who made innovations on projector technology to file the patent in his name, while he gave them a decent one-time fee. People thought that was a morally questionable move, and Edison replied, "Everyone steals in industry and commerce. I've stolen a lot myself. The thing is to know how to steal." Later, Edison tried to monopolize the film industry and forced filmmakers to move to California to avoid his many lawsuits, giving birth to Hollywood.

MYTH: Americans were always the good guys in World War II

World War II is often hailed as the last war where there were clear lines between the good guys and bad guys. The Axis Powers wanted to take over the world. The Allies wanted to stop them. But nothing is ever that simple. American GIs were responsible for war crimes on par with the acts committed by their Japanese and German enemies.

For example, in 1943, U.S. soldiers invaded the island of Siciliy and — inspired by an intentionally ambiguous speech from Gen. George S. Patton — murdered at least 77 POWs in what's known as the Biscari Massacre. Even though they were fighting for freedom, these troops threw the Geneva Convention right out the window. It was even worse for European women. GIs were responsible for approximately 14,000 rapes in England, Germany, and France from 1942 to 1945.

However, things took a truly barbaric turn in the Pacific Theater. Even though it was illegal, American troops made a habit of taking trophies from dead Japanese soldiers, and not fumbling through their pockets or taking their weapons. GIs actually lopped off ears, pulled out teeth, and took bones as mementos to send their parents, wives, and girlfriends. Life magazine featured a photo of a woman writing a letter to her Navy boyfriend, thanking him for the Japanese skull sitting on her desk.

This barbarous behavior went all the way to the White House. In 1944, a congressman gave President Roosevelt a letter opener made from a Japanese arm, and the president responded with, "This is the sort of gift I like to get." If the soldiers of World War II were indeed America's "greatest generation," that says a whole lot about every generation afterward.

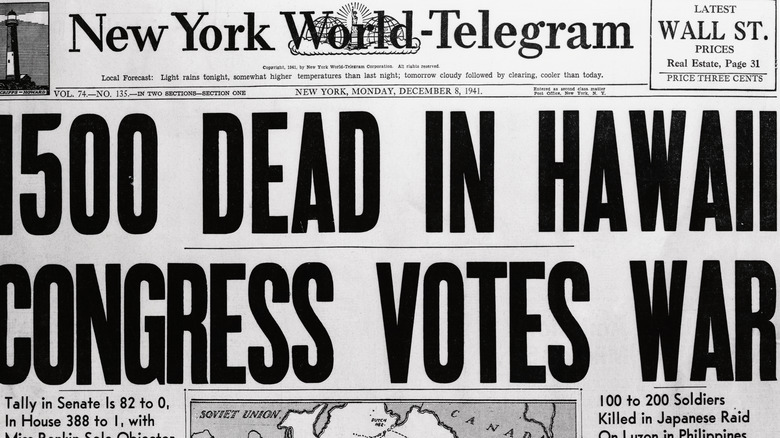

MYTH: America was only attacked once during World War II

Everybody knows the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The sneak attack left 2,403 Americans dead, and it forced the U.S. into World War II. But despite what many people think, this wouldn't be the last time the Japanese military dropped bombs on U.S. soil.

In February 1942, a Japanese sub fired a couple shells at an oil field near Santa Barbara. Then in June, another sub lobbed some explosives at a fort on the Columbia River. That same year, a pilot named Nobuo Fujita dropped four incendiary bombs into the forests of southern Oregon, hoping to spark massive fires. Thankfully, the woods were just too wet, but tragically, the Japanese had more success with their "fugos," fire balloons that floated across the Pacific Ocean and landed on U.S. soil. While only one of around 6,000 balloons actually killed anyone, that "fugo" claimed the lives of a pregnant woman and five children in Oregon.

Crazier still, the Japanese straight-up invaded the Aleutian Islands and set up bases in the Alaskan Territory, prompting an island-hopping campaign that lasted from June 1942 to August 1943. Of course, the Japanese weren't the only ones trying to bring down the U.S. The Nazis were involved, too, only instead of dropping bombs, they were dropping saboteurs. In 1942, U-boats deposited eight saboteurs in both Florida and New York. These agents planned on destroying as many railroads, bridges, hydroelectric plants, and factories as possible. They even wanted to shut down the Big Apple's water supply. Fortunately, two of the Nazis got cold feet and sold their buddies out to the FBI before any damage was done.

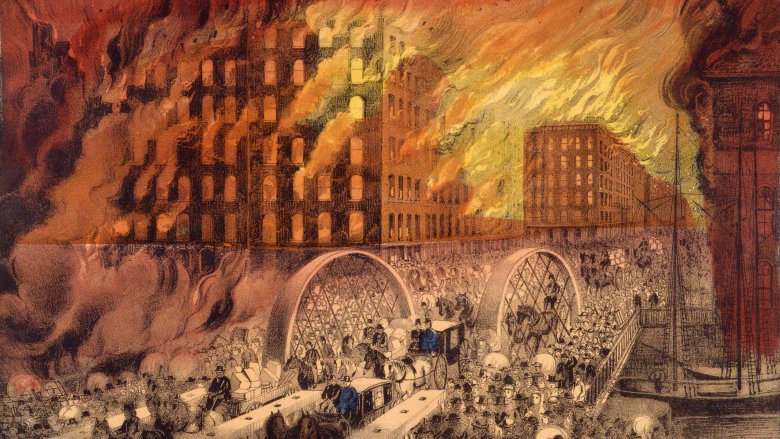

MYTH: A cow started the Great Chicago Fire

One of the worst disasters in American history, the Great Chicago Fire raged for two days in October 1871. By the time it died down, 300 people were dead and around 100,000 were homeless. The fire had ripped through 2,000 acres, leaving $200 million worth of property in ashes. Naturally, when something this horrible happens, people want a scapegoat, and unfortunately, the survivors turned on Catherine O'Leary, an Irish immigrant who made her living selling milk. Newspapers claimed O'Leary had been milking one of her cows on October 8 when either she or the animal knocked over a lantern that started the blaze. Needless to say, these stories didn't do much for O'Leary's popularity.

In response, O'Leary said she'd been asleep when the fire started and that she never milked cows in the evening. Shortly after the fire, an official inquiry stated there was no way to prove who or what started the fire, but that didn't stop people from blaming O'Leary. When she finally died in 1895, people said it was of a broken heart. Even to this day, it's widely believed that O'Leary's bovine started the blaze.

However, several reporters who first leveled the accusation admitted they'd either made up the story or heard the tale from super-unreliable witnesses. Couple that with the findings of the 1871 investigation, and it's beginning to look like there was no cow-spiracy on the part of Catherine O'Leary, even though the fire did start somewhere in her area. In fact, some have recently come to suspect her neighbor, Daniel Sullivan, who first reported the fire, as many parts of his story don't stand up under scrutiny. Regardless of who or what was at fault, the Chicago City Council realized there was no good reason to blame O'Leary, so in 1997, they cleared both Catherine and her infamous cow.

MYTH: Only whites owned slaves

By 1860, there were 4.4 million Black people in the United States, and 3.9 million of them were slaves (via The Root). It is definitely true that the vast majority were bought, owned, and brutalized by white people. However, even though they were in the minority, there were a surprising number of slave owners who actually weren't white.

For example, wanting to fit in with white society, wealthy members of the Cherokee nation owned around 4,600 Black slaves. And in an ironic twist of fate, when they were forced down the Trail of Tears, the Cherokee forced 2,000 Black people to go with them. According to Vocativ, the tribe even sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War because they didn't want to lose their slaves.

Stranger still, in 1830, about 3,700 Black freedmen owned slaves. In fairness, many bought their own family members to protect them, but that wasn't always the case. Take William Ellison, for example. One of the wealthiest men in South Carolina, Ellison was a Black man who used his 63 slaves to work his 900 acres of property. And he wasn't at all concerned with keeping friends and family members safe. This guy just wanted free labor to keep that cash coming in.

And before Ellison was even born, there was Anthony Johnson, a Black man who won a court decision in 1654 to keep a Black indentured servant as a slave. As historian R. Halliburton Jr. points out, this was "one of the first known legal sanctions of slavery," helping to set a terrible precedent that would only end with the deadliest war in U.S. history.

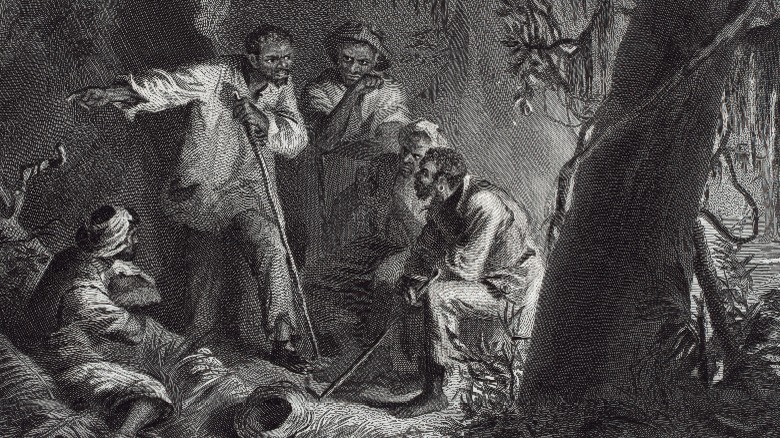

MYTH: Slaves never fought back

If slavery in America lasted around 250 years, why weren't there more slave revolts? Sure, there was Nat Turner's rebellion and the Amistad mutiny, but other than those two super-famous incidents, why didn't more slaves fight back against their captors? Well, they totally did. Some historians estimate there were over 300 revolts and conspiracies, and while most of those were put down violently, a few were surprisingly successful.

For example, there was the Stono Rebellion of 1739, where around 100 slaves overthrew their white masters and fled for Spanish Florida, where slavery was illegal. Tragically, these heroes were cut down by the English, but the group made history with the biggest slave rebellion in the 13 colonies. Then there was the German Coast Uprising of 1811, where slaves attacked a militia warehouse, armed themselves to the teeth, and tried to capture New Orleans. They were defeated after two days, and around 100 Black prisoners had their heads cut off and placed on poles along the side of a road.

There was the time when 300 slaves teamed up with 20 Native Americans to seize a Florida fort, and there was the 1800 incident where Gabriel Prosser assembled an army of 1,000 slaves but was undermined by a traitor and bad weather. In 1842, slaves turned on their Cherokee and Creek masters and made a brave but futile run for the Mexican border. On a happier note, in 1841, slaves aboard the ship Creole staged a mutiny and sailed to freedom in the Bahamas. And if you want to look outside the U.S., in 1791, Toussaint L'Ouverture sparked a massive slave rebellion in Haiti, leading to the country's independence.

On a smaller scale, there are an untold number of incidents where individual slaves stood up to their cruel masters. Before escaping to freedom, abolitionist Frederick Douglass actually went hand-to-hand with an overseer named Edward Covey. When Covey pulled out a whip, Douglass started throwing punches, and the two actually fought to a tie.

MYTH: The guillotine was named after its inventor

First used in 1792, the guillotine hacked off around 15,000 heads during the French Revolution, but even after Robespierre and his posse were put down, the French government kept this razor-bladed invention around, using it to behead bad guys until its final kill in 1977.

But how did this horrific device get its unusual name? It got its moniker from Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, but despite what some think, he didn't actually invent the machine. In fact, he didn't even like the idea of capital punishment. But in the early days of the French Revolution, Guillotin hoped to make the death penalty less painful by proposing a machine that could cleanly chop off someone's head in mere seconds. As a member of the French National Assembly, he pitched his idea in 1789, but the job of actually inventing the device fell to Dr. Antoine Louis, a surgeon and secretary at the prestigious Academy of Medicine.

After Louis designed the device — probably inspired by earlier machines like the Halifax Gibbet and the Scottish Maiden — it was assembled by a German guy named Tobias Schmidt. The completed product was labeled the "Louisette" or the "Louison" after its inventor, and it was tested on human bodies before claiming its first victim in 1792. However, because Guillotin was the man who originally proposed the idea, and thanks to popular songs incorrectly asserting he was the creator, people soon started calling the device "le guillotine."

After he died a natural death at 75, his family begged the French government to rename the machine. But when the government said no, the Guillotins changed their own name, hoping to distance themselves from those 15,000 decapitated corpses.

MYTH: Deep Throat was the man who brought down Nixon

The Watergate cover-up is possibly the most notorious political scandal in U.S. history, one that brought down a president and completely changed the way Americans viewed their government. And when people recall the incredible events that led to Richard Nixon's resignation, they often picture a mysterious man lurking in the shadows of a parking garage, a secret informant who helped Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncover a real-life conspiracy.

For years, this undercover agent was known solely as "Deep Throat" (both a nod to his role as "deep background" and to an adult film of the same name), and thanks to both the book and movie adaptation of "All the President's Men," this enigmatic figure became a permanent part of the American consciousness. Eventually, his true identity was revealed in 2005 as Mark Felt, the second highest-ranking member of the FBI during the 1970s. But even if Felt had never come forward, Deep Throat would have always been remembered as "the man who brought down the White House."

Only that's not exactly how it happened.

While Deep Throat was an important player in the Watergate story, his role in Nixon's downfall has been massively overblown. As it turns out, Deep Throat mostly didn't provide Woodward and Bernstein with information they didn't already know. Instead, as Bernstein explained, "Deep Throat largely confirmed information we had already gotten from other sources" (via The Washington Post). Both reporters also made it clear they had "several dozen" sources pointing them in the right direction, not just Felt, and Woodward even went so far as to tell the Associated Press that "this portrait of [Deep Throat] as 'the man who brought down the White House' just isn't accurate."

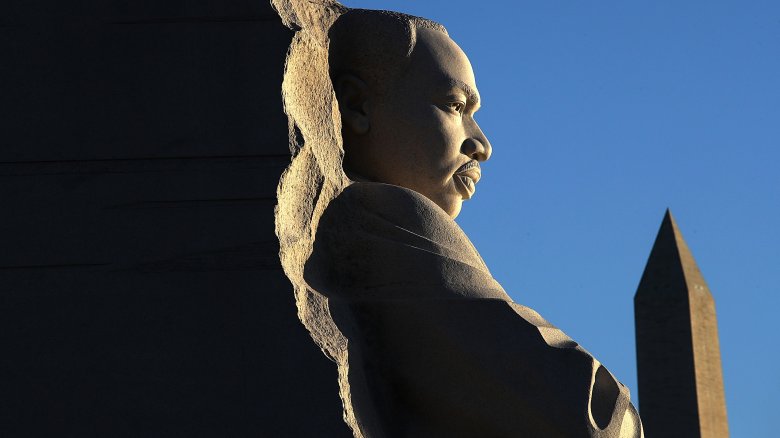

MYTH: Martin Luther King Jr. was always against violence

Martin Luther King Jr.'s name is synonymous with noble ideas like "civil disobedience" and "nonviolent resistance." Along with Mahatma Gandhi, King wrote the playbook on how to peacefully resist a totalitarian government, as demonstrated by his campaigns in Birmingham and Selma. During these marches, King and his followers never fought back, even when they were arrested, blasted with fire hoses, and beset by dogs. But everyone's opinions evolve over time, and while he eventually became America's most famous pacifist, King wasn't always so eager to turn the other cheek.

King first became a national figure thanks to the Montgomery Bus Boycott. After Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white passenger, King organized the resistance movement that forced the city of Montgomery to integrate its bus systems. Needless to say, the boycott didn't win King any fans in the racist community, and as a result, someone bombed the reverend's house in February 1956. But instead of letting things slide, King decided he would be ready the next time someone came for him or his family.

After the attack, armed guards kept a vigilant eye on King, and he applied for a concealed carry permit. As you might expect, his application was denied, but that didn't stop King from stockpiling guns. The man's house was full of firearms (according to Adam Winkler, one of King's advisers described the place as "an arsenal," as per the Huffington Post), and once a journalist visiting the King home almost sat on the pastor's loaded pistol. Eventually, King would change his mind on the matter and get rid of his weapons, but for a brief moment, one of the most peaceful men on the planet was packing a whole lot of heat.

MYTH: Europeans introduced scalping to Native Americans

When Europeans arrived in North America, they didn't exactly hit it off with their new new neighbors. Some historians believe 20 million Native Americans were murdered by Old World weapons and European illnesses, but there was savagery on both sides, especially when it came to the subject of scalping. However, many believe Native Americans learned the awful art of taking scalps from their European enemies. In fact, there's a common belief that before white settlers showed up, Native Americans never even considered the idea of lifting somebody's scalp.

In reality, certain Native American tribes were taking scalps long before white people showed up, but Europeans also had their own bloody history when it came to skinning enemies. As pointed out by Cecil Adams of "The Straight Dope," white men were scalping people "from the Stone Age till as late as 1036 in England." On the flip side, in North America, archaeologists have found scalped skulls dating back to A.D. 1325, long before Columbus and company arrived. Historians have even discovered evidence that scalping occurred before the Vikings sailed across the Atlantic. And as historian James Axtell writes, when Europeans first showed up, they found certain tribes like the Delaware, Mohawks, and Algonquins already had scalping down to an art.

However once the Europeans moved in, everybody stepped up their scalping game. When white settlers arrived in the New World, they put out bounties for the hair of their Native American enemies, encouraging tribes that had never practiced scalping before to take up a new bloody hobby. (Plus, there were plenty of white people who paid their bills by scalping Native victims.) And with white people handing out cash for human trophies, scalping became widespread across North America, resulting in a whole lot of people on both sides winding up with incredibly close haircuts.

MYTH: The Alamo was Mexican villains vs. American heroes

The battle at the Alamo is usually taught as a bunch of heroic white Americans fighting for freedom against the dastardly Mexicans. You picture John Wayne standing stoically, a perfect American hero brave enough to fight to the death. Sadly, that barely resembles what happened.

When Mexico gained independence in 1821, they weren't sure what to do with Texas. Eventually, they offered the land to Americans to live cheaply and tax-free for seven years as long as they swore allegiance to Mexico and became Catholic. Mexico was so eager to settle Texas, they even let landowners keep slaves. Slavery had been abolished in Mexico for years, but they were willing to bend the rules for slave-loving white guys. By 1830, Americans outnumbered Mexicans in the Texas area five to one. President Santa Anna issued a stop on immigration from the U.S., but those pesky American illegal immigrants kept pouring in. By 1834, Mexico started getting rid of illegal aliens. Since it seemed heartless and rude to remove peaceful immigrants who simply wanted a better life in Mexico, Texas got ready to fight for independence.

At one point, David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Travis got to the Alamo, a decaying fortress the Texans had seized from Mexico, to join the fight for freedom. Here's where things divert from history class. These three men weren't ideal heroes. Bowie was a slave smuggler and con man, though he got along well with the Tejano community of the state. Travis was a lawyer who didn't care for the Mexican people who lived in the Mexican territory. Crockett was the closest to his fictional counterpart. A very popular military man who served in Congress, Crockett was a charming celebrity of the age.

When the battle of the Alamo commenced, it was far from a war of white versus brown. Tejanos, Americans, native Mexican Indians who spoke no Spanish, and slaves all fought for the side of Texas. Santa Anna was brutal, and in the end, most of the American soldiers fought to their death. Santa Anna burned their bodies in a heap in front of the destroyed mission as a lesson to future rebels.

Texans spread the word of the Alamo and greatly exaggerated the tale. When the rebels and Santa Anna's men fought again, the Texan soldiers killed any Mexicans they could find, whether they were soldiers or not. The Smithsonian Magazine wrote that a young Mexican drummer boy asked for his life and died for the request. The slaughter in the name of the Alamo was just as bad as the battle of the Alamo itself, if not much worse. And the efforts of all the brave Tejanos, slaves, Indians, and all the other non-white people were completely erased from history

MYTH: Manhattan was sold for $24

This story has been retold in textbooks for more than a century: In 1626, a representative for the West India Company purchased the island of Manhattan for a handful of beads worth $24. The real story is more complicated.

This is often incorrectly viewed as a kind of swindle, in which the Dutch dazzled the local people with foreign jewelry, tricking them into accepting a terrible price. In reality, the Indigenous people who accepted beads as part of their trade deals were participating in a well-established trade strategy. Glass beads may be viewed as trinkets today, but in the past, beads were a legitimate trade currency. The beads were also certainly worth more than $24. Today, it is most commonly estimated to have been worth around $2,000.

Whether or not the deal was actually a sale at all is still debated, as it's possible the price was actually intended to be a rental fee, guaranteeing the Dutch settlers the temporary right to hunt or live in Manhattan. Some historians believe that the Indigenous people who "sold" the land never actually owned it in the first place and were grifting the West India Company. It is believed that those who agreed to the sale were from a small village in modern-day Long Island, who were more than happy to "sell" Manhattan, since they didn't live there in the first place.

MYTH: Marie-Antoinette said, 'Let them eat cake!'

If there are two famous common knowledge facts about Marie-Antoinette, they are probably that she was beheaded by guillotine during the French Revolution and that, when warned that her people were starving and running out of bread, she naively replied, "Let them eat cake!" While there is no doubt that Marie-Antoinette was born into extreme privilege and likely had no comprehension of the horrors of starvation that her people faced, she almost definitely never said this particular phrase.

While today almost everyone associates this phrase with Marie-Antoinette, it actually has been attributed to many noblewomen throughout history, long before Marie-Antoinette was even born. It's likely that this story became associated with Antoinette both because it fit well with her reputation as a vapid rich woman from a foreign country who was sending France into debt, and because the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau claimed it had been spoken by a princess, and some mistakenly believed he was referring to her.

MYTH: Helen Keller's greatest accomplishment was learning to speak

Helen Keller was born in 1880 and was both blind and deaf. Famously, a teacher named Anne Sullivan designed a curriculum to teach Keller to communicate. The story of her childhood is often shared with children as an example of overcoming adversity through hard work, but as an adult, Keller used her newfound voice to advocate for others.

Keller was a devoted socialist and supporter of workers' rights. She was also an outspoken disability advocate. She wrote articles, gave speeches, promoted birth control when it was still highly controversial, supported the newly founded NAACP, marched on picket lines, and educated people about the struggles disabled workers faced — particularly when their disabilities were caused by negligent employers. She went on to co-found the ACLU.

As noted in a Time interview with Haben Girma, a Black disability rights lawyer who is also deaf and blind, reducing the powerful advocate Helen Keller in the public eye to a child still learning to talk is part of a larger cultural issue of infantilizing disabled adults. There are also clear political motivations for suppressing the most interesting and controversial facts about Keller's life in favor of a palatable inspirational story. Even in her own times, Keller was investigated by the FBI for her activism, and some educators may be reluctant to present their students with such a radical hero.

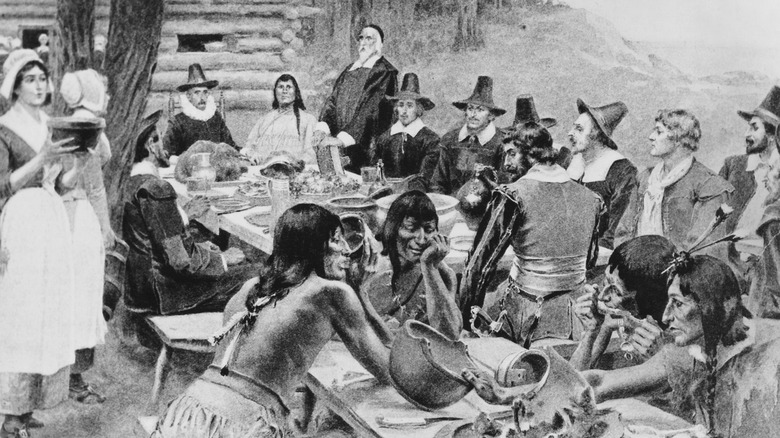

MYTH: Native Americans were invited to the First Thanksgiving

Many believe that the Plymouth Colony pilgrims gathered their savior Squanto and his tribe together for a massive feast to thank them for their help in growing crops. This story, while beautiful, is a myth.

The man known as Squanto was actually a Wampanoag man named Tisquantum. He was able to help the pilgrims, not only to avoid starvation but also to communicate with the people who already lived there because he already spoke English himself. He had learned the language after being kidnapped and trafficked as a slave by the British, years before. Incredibly, he was able to escape, and after working for a British merchant for many years, negotiated his way back to his home. Tragically, the arrival of Europeans in his homeland had caused a horrendous epidemic that took the lives of tens of thousands. Without a family to return to, Tisquantum (Squanto) chose to help the pilgrims.

The pilgrims really did have a harvest celebration, but they did not invite the local people as a sign of gratitude for Tisquantum's help. Rather, celebratory gunfire from the pilgrims had caused a tense situation when the surviving Wampanoag interpreted it as an act of war. After the conflict was resolved, it's possible that they provided some food to the Plymouth Colony. But as a specific, friendly, singular gathering, the "Thanksgiving" celebrated today didn't likely happen. It's more likely that it memorializes several feasts of the Pilgrims, including one that celebrated the Mystic Massacre, where colonists murdered several hundred Pequot in Connecticut in retaliation for ongoing conflict.

MYTH: Betsy Ross sewed the first American flag

One of the most popular stories of the Revolutionary War is the seamstress Betsy Ross fashioning the very first American flag at the request of George Washington, but in reality it is just a story and not historical fact. There was a real woman named Elizabeth Ross, but there's no reason to think that she had anything to do with the flag. In reality, the original American flag was likely designed by flag designer and continental congressman for New Jersey, Francis Hopkinson.

The real Betsy Ross was a Quaker woman from New Jersey who was kicked out of her community for marrying a Protestant. She and her husband ran an upholstery business together in Philadelphia until he was killed in the war. The church that the widowed Ross attended was popular with the founding fathers, with at least 15 well-known members of the Continental Congress attending regularly, so it is likely that they were at least acquainted socially. It is also true that Ross produced flags, among other goods, for the Continental Army. It wasn't until several decades after her death that the story that she had created the first flag appeared — likely invented by her grandson.

MYTH: Pocahontas is a love story

The popular story about Pocahontas that has fascinated generations comes directly from one of the main players, English colonial explorer John Smith. According to Smith, he was captured by Algonquin leader Powhatan and was going to be executed until Powhatan's beautiful daughter begged for his life because she was in love with him. Smith was either mistaken or lying. Most bizarrely, it is nearly identical to a far older Scottish tale about a Turkish princess.

Unlike the love-struck young woman John Smith described, Pocahontas was a curious, fun-loving, and intelligent child at the time, around 11 years old. She and John Smith really were close and taught each other their respective languages. Years later, Pocahontas was captured by the English. Her father attempted to ransom her back, but by then they had already given her a new, English name and married her to a man named John Rolfe. Whether or not Pocahontas agreed to the marriage is unknown. On the ship to England, Pocahontas died unexpectedly. Her father always suspected she had been poisoned.

It's unknown exactly why John Smith chose to misrepresent his relationship with Pocahontas, but his version of the story has endured. As described by historian and expert on Pocahontas Camilla Townsend in an interview with Smithsonian, the traditional Pocahontas story has always been popular with white Americans because it depicts an Indigenous person choosing a European religion, culture, and husband over her own.

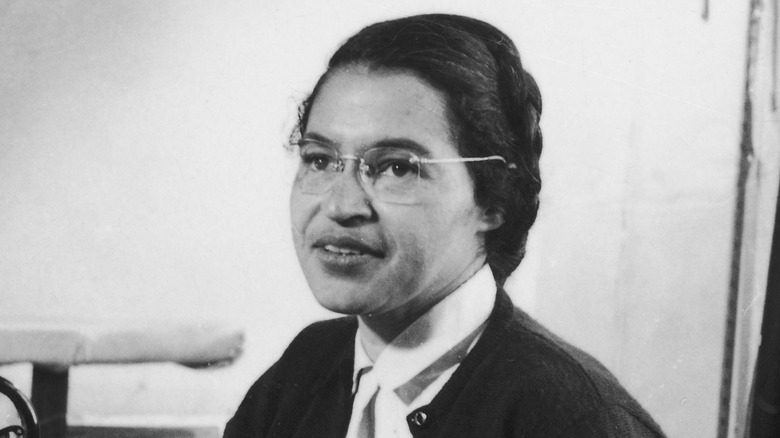

MYTH: Rosa Parks spontaneously stayed in her seat

Rosa Parks is best remembered for refusing to give up her seat on the bus, challenging segregation and sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Many have assumed that Parks was a tired old woman who spontaneously decided she wasn't giving up her seat, but that is not the case. Parks herself is quoted by Women's History as clarifying, "People always say that I didn't give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn't true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

When Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat, she was already a respected civil rights leader. Her choice to stay in her seat was a calculated decision and a brave act of protest, not a spontaneous decision. This protest was likely inspired by a different Black woman's spontaneous decision, however: 15 year-old Claudette Colvin. After learning about Black history in school, Colvin refused to submit to the racist policy on her local bus and give up her seat for a white passenger. In an interview with NPR, Colvin stated, "It felt like Sojourner Truth was on one side pushing me down, and Harriet Tubman was on the other side of me pushing me down. I couldn't get up."

MYTH: Mussolini made the trains run on time

The phrase "Mussolini made the trains run on time" is often used to imply that living under a controlling fascist regime would at least be efficient. The ethics of that particular argument aside, the "fact" that it is based on is a lie. The Italian transit system under Benito Mussolini was a mess.

The perception that the trains were particularly punctual was an active deception. As described by the Independent, the perception of efficiency under fascism was a piece of propaganda, being actively spread by the regime. In addition to planting news stories about how fast and timely the trains were, tourists traveling through the country were put on trains specifically run to impress them. These were more frequently on time, convincing foreigners that they were efficient. The trains that Italians actually used were much, much worse. They were usually poorly maintained, leading to serious delays. In fact, the trains were so poorly run that even the special tourist trains were regularly delayed. The railway system was actually so poor that it caused problems during World War II, because only about 20% of the trains that ran through the Alps were functional.

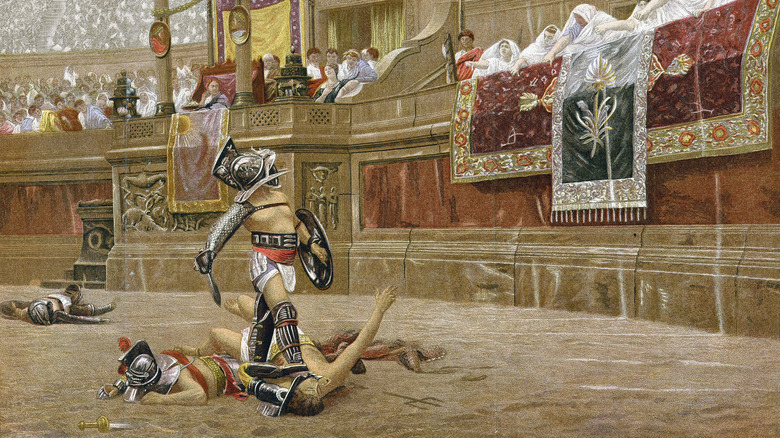

MYTH: Gladiators always fought to the death

In popular culture, gladiator fights are usually depicted as a no-rules battle royale to the last man standing while the watching crowd was baying for blood. These fights certainly could be gruesome and people did die in the Colosseum, but contrary to popular belief, gladiator fighting had rules just like any other sport. Usually, that included avoiding killing your opponent.

As described in James Grout's Encyclopaedia Romana, there were executions in the Colosseum, particularly criminals and unrelenting Christians. Professional gladiators also sometimes were killed during the fight, but it is estimated that they had an average 90% chance of surviving every time they fought.

As violent as they were, gladiator fights weren't without rules. In fact, each fight is believed to have had a pair of highly respected referees observing to ensure that all of the fighters followed the rules. As described by historian Sarah Emily Bond, these early umpires had the authority to disqualify gladiators who were breaking the rules.

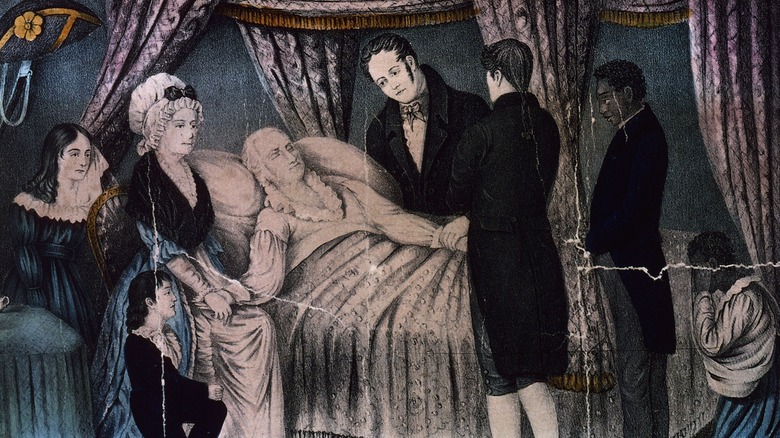

MYTH: George Washington freed his slaves

The first president of the United States, George Washington, and his wife personally claimed hundreds of men, women, and children as property. It is commonly believed that although he relied on the exploitation of enslaved people throughout his life, he privately disagreed with the institution and ordered that all the people enslaved on his estate be freed upon his death. The reality is more complicated.

It is true that in George Washington's will, he expressed the desire to release the enslaved people who had been forced to serve him throughout his life, but he also stated that their freedom would be granted upon his wife's death, because, until then, doing so might cause problems for her. Also, his will only stipulated the freedom of his slaves. Considering Martha Washington came to the marriage with slaves of her own, who accounted for more than half of the enslaved at Mount Vernon, many remained in bondage for the rest of their lives, since they were inherited by her grandchildren.

George Washington's will did stipulate the release of a single man upon his death – a Revolutionary War hero named William Lee. A year after his death, it is believed that Martha Washington came to fear that the estate's slaves might rise up against her, so she finally granted the people her husband had enslaved their freedom.

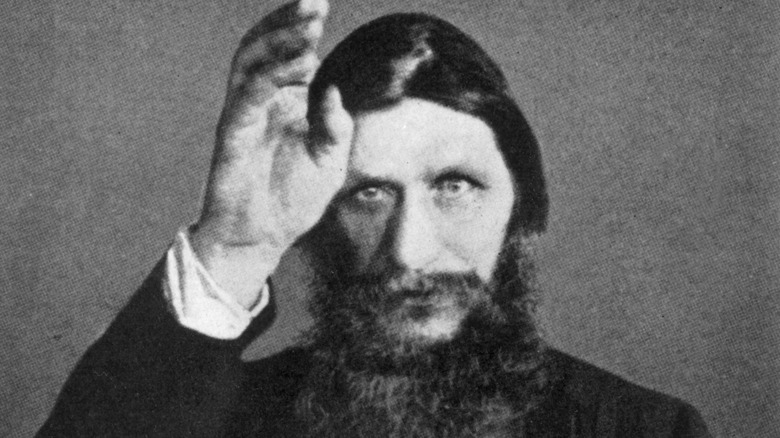

MYTH: Rasputin was almost impossible to kill

Grigori Rasputin is probably one of the most mythologized historical figures in history. Often, lies about Rasputin and his abilities come straight from the man himself, who thrived on spreading misinformation and transforming himself into a legend. The most remarkable story may be that of his death, however, and that story was started by his assassin.

The most widely known story of Rasputin's death was told by Felix Yussupov, the man who killed him. According to Yussupov, he had served Rasputin multiple glasses of wine and cyanide, to which the "mad monk" had proved completely immune. He claimed that he then shot Rasputin in the chest, but he still would not die. In order to make Rasputin stay dead, his assassin claimed that he had finally had to drown him in the river.

This remarkable story has remained immensely popular and is still the best-known account of Rasputin's death, but the autopsy report told a far more mundane story. The authorities found that Rasputin had been shot in the head, died, and then his body was thrown in the river. It is likely that Yussupov made the event more dramatic in the retelling in order to make himself seem more heroic.

MYTH: Indigenous peoples didn't own land

One of the most common myths about the colonial era is that Indigenous Americans were baffled by colonization by Europeans because they had no concept of land ownership and therefore didn't realize that the European settlers were taking something away from them. In reality, many communities living in North America had extensive legal systems of their own before the arrival of Europeans. These included rules about owning land.

As described in The American Historical Review, this belief that the people who lived in the Americas before the arrival of Europeans had no concept of owning land comes from philosopher John Locke, who believed that Indigenous peoples were wild men who roamed the forests hunting and never worked the land. He believed that only white people grew crops or cultivated land. This idea was based on assumptions about people of color and had no basis in reality. The vast majority of people who lived in the Americas were farmers, just like in Europe. Even hunter-gatherer communities had designated land that they lived on, worked on, and maintained for future generations.