Hellish Parts Of The Handmaid's Tale Inspired By Real History

Margaret Atwood's seminal work of dystopian fiction is over three decades old, and yet it seems to have more resonance than ever before. Recent tensions between both sides in the "culture wars" have thrown the concerns that run through the novel into an even sharper focus.

Both the book and TV series of "The Handmaid's Tale," as well as the follow-up novel "The Testaments," have served not just as a warning about the future but as a reflection of the present. The role of women, and what can happen to their rights when totalitarianism is allowed to flourish, can seem to many like a nightmarish vision of an imagined parallel world — one safely confined to TV and fiction. The TV series has been accused of being so grim that it strays into "torture porn" territory (via Digital Spy), with the implication being that the events are not truly realistic.

Yet author Margaret Atwood has stated that everything in the book was inspired by real-world events, and that her work is a clarion-call against complacency. Much of what people assumed she was predicting had already happened, as detailed by The Guardian. Some of the most terrifying moments in history that she was parodying are listed below.

The death of Mary Webster

Margaret Atwood dedicated her novel to Mary Webster, a real-life "witch" in Puritan-dominated America. According to the New England Historical Society, Webster and her husband William lived on very little and sometimes needed help from the town of Springfield, Massachusetts, where they lived to make ends meet.

Poverty contributed to Mary being irascible and bad-tempered, and relations with her neighbors became strained. She was accused of witchcraft after rumors spread that she had cast a spell on local cattle and horses, ensuring that they could not pass her house. It resulted in a number of nearby cart-drivers beating her until the spell apparently broke. Similarly, a burn mark on her arm from an accident with boiling water was claimed by her neighbors to be a mark of the devil.

She was accused of witchcraft and put on trial in 1683, but was declared "not guilty" by the court. It was the era before the mass accusations of the Salem Witch Trials, and in 1675 another woman, Mary Parsons, had also been exonerated. Yet Webster was still seen as a witch by the community around her, with the mysterious illness of a man named Philip Smith blamed on her. She was dragged out, hanged by a number of the townsfolk and dumped in the snow, in the belief that it would ease Smith's survival. Yet somehow, Webster survived. The case inspired the persecution of women and public executions that pepper Atwood's book.

The Canadian politician who urged women to reproduce

Margaret Atwood conveniently kept hold of the box of newspaper clippings she collected while researching for "The Handmaid's Tale." One of the more bizarre ones from her own homeland contains details of the comments made by MP Dave Nickerson, a man who cited the falling birth rate in Canada as a reason to persuade people to breed with more "vigor."

In an interview with her publisher Penguin, Atwood highlighted how the apparently "progressive conservative" politician had grown concerned about figures from Statistic Canada showing that Canada's birth rate had reached an unprecedented low. He went so far as to say that "It ought to be public policy to encourage families to have more children."

The concern about falling birth rates is reflected in the book's dystopian landscape, where infertility is widespread among everyone, but blamed on women. The government of Gilead opts for forcing fertile women — the handmaidens — to have sex with senior male figures, to provide them children that their "barren" wives, the highest position Gilead women can occupy, cannot. They wear red cloaks to indicate ripeness and fertility, the only part of them that Gilead values. Women who can no longer bear children are known in the TV show as "Marthas" and are considered to be second-class citizens, forced to do chores and act as servants.

The Islamic Revolution in Iran

Before the uprising in 1979 that overthrew the Shah, rights for women in Iran had been improving. Education was free for boys and girls, many women attended university and held roles in politics, and they had the right to get divorced and apply for custody of children. The legal age for marriage went from 15 to 18, as highlighted by Evie Magazine.

However, with the rule of Ayatollah Khomeini came increasing restrictions, such as women being made to wear the hijab from the age of 9 while in public. Women who refused risked corporal punishment or imprisonment. Atwood drew inspiration from the situation in Iran when imagining the conservative dress codes of the women in Gilead. As well as having to wear red, the handmaidens are forced to cover their hair indoors with white caps, and white bonnets while outdoors.

Similarly, Iranian women's rights in the home were heavily restricted during the 1980s, with laws around divorce, inheritance, child custody, and sexual assault redrawn to be heavily in favor of their husbands. Child marriage and polygamy became legal, while access to abortion and contraception has since become heavily restricted in Iran due to the country's stagnating birth rates — an issue that is the driving force behind the founding of Gilead. The end of Margaret Atwood's novel also mentions both Iran and Gilead in the endnotes, during a fictitious future conference of historians that takes place in 2195, one that describes the two states as "monotheocracies."

The anti-feminists of the Religious Right

The rise of the Religious Right in America in the 1980s, pioneered by President Ronald Reagan and conservative activists like Phylis Schlafly, made feminists fear that fertility rights would be rolled back and that conservative evangelical Christians would move the U.S. closer to a theocracy.

The character Serena Joy, the most senior wife in Gilead, and her push for this vision of America, was strongly inspired by Schlafly, as detailed by The New Republic. Prior to the 1980s, she had campaigned successfully against the implementation of the Equal Rights Amendment, claiming that second wave feminism did not respect how "most women want to be wife, mother, and homemaker — and are happy in that role."

Yet unlike Schlafly, Joy ultimately gets her comeuppance, even if it comes at the expense of those around her. Before the rulers of Gilead take over, rather than being a housewife, she has an active role as a campaigner, a lobbyist, an author, and an evangelical broadcaster. When her vision of a perfect society is made flesh, she ends up confined to the home, forbidden from touring or giving speeches and instead living a life of full subservience to her husband — one that leaves her quietly bitter. In the process, it highlights how fundamentalism only thrives with the complicity of other women. The warning to conservative women is clear: Don't end up in a prison of your own making.

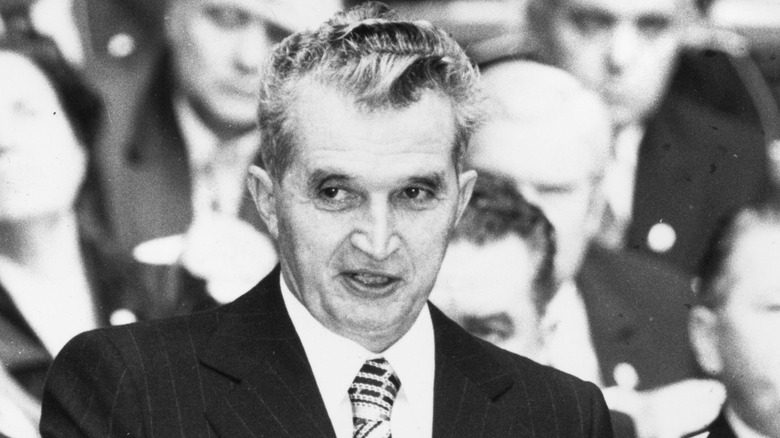

Compulsory pregnancy in Ceausescu's Romania

The idea that increased fertility rates matter more than individual lives had a thriving shelf-life before Margaret Atwood's novel. In her interview with Penguin, she describes reading about how the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu had introduced Decree 770 in the first year of his rule in 1966. It mandated that women with fewer than four children could not have abortions. Such women were subject to pregnancy tests every three months, and if they had not managed to get pregnant between tests, then they were required to explain why. Those who were pregnant but didn't give birth (possibly due to a highly dangerous black market abortion) could face prosecution. Contraception and the pill were eventually banned altogether (via The Guardian).

It was rooted in the belief that population growth would lead to increased economic growth. In the dictator's words, the fetus was declared to be the property of "the entire society." The forced pregnancies of fertile women in Gilead, along with the separation of women from their children, found their real-work counterparts here.

In Romania, the consequences were distraught. Many women could not afford to keep that number of children. The law led to the country's orphanages bursting at the seams and, once they became under-funded in the 1980s after Ceausescu diverted the state budget towards the national debt, were notorious for neglect. Children were beaten, starved, and denied access to medical care, to the point where it became a global scandal. Many who survived remain traumatized.

The People of Hope cult

It would be easy to think that the prophetic status of "The Handmaid's Tale" was a recent phenomenon. Yet from the time the book was published, people were identifying modern-day parallels. The People of Hope cult was a joint initiative, started in the 1970s by a stockbroker and a Catholic priest with deeply conservative ideas about Christian theology and the role of women. They encouraged female adherents to be "Handmaidens of God" by coercing each other into full subservience to the men in their lives. Young people were forbidden from dating unless they were already married, as was reported by a New York Times piece from 1986.

The cult caused controversy in the small New Jersey parish, Little Flower, where it started, as it was linked to a fundamentalist group in Michigan called the Sword of the Spirit which was accused of having extreme views not endorsed by the diocese.

The subservient role of the women of Gilead strongly echoes the cult. A local newspaper in New Jersey reported that local Catholic people saw the group's members as "sheepish" and engaged in "brainwashing" and infiltration. It even highlighted how this "little known" home-grown sect was referenced by Margaret Atwood as inspiration, although how she did so is unclear due to news stories about them not emerging until after the book was published. Whether it inspired or ran alongside the book, the cult clearly fed people's fears that Gilead might be closer than they thought.

Exile in toxic wastelands within the Soviet Union

Citizens of Gilead who contravene the regime's harsh laws are shown being sent to toxic waste grounds to live out their shortened days doing hard manual labor in horrifying conditions. It was a practice pioneered during the Cold War, when Czech Soviet prisoners in the 1940s and 1950s were forced to do hard labour in uranium mines more than 3,000 feet below ground as part of efforts to build an atomic bomb.

The levels of radioactive gas and particles in the air severely shortened the life-span of those convicted, with many contracting and dying of lung or intestinal cancer, as highlighted by The New York Times. Numerous workers were already smokers, making for a deadly combination of factors in terms of their health. As an added humiliation, they were often forced to sleep standing up in hot and stifling concrete chambers. There was little chance of escape, as the camps were rimmed with barbed wire and overseen by armed guards in watchtowers. One former inmate said that they were seen as "numbers, not people, just meat." Yet despite the harshness of their surroundings, some inmates found themselves returning to work as a way to escape persecution for their anti-Soviet views.

The punishment of sending recalcitrant handmaids to the colonies to shovel radioactive waste is a terrifying facet of the TV series, showing the characters turning on each other even more than usual in such a life-or-death environment.

Mormon polygamy

Margaret Atwood describes in her interview with Penguin how Mormon marriage practices inspired the forced polgymay depicted in her novel and the TV series. She researched how traditional Mormons in the U.S. sometimes took on multiple wives, often without declaring this to their first wife. This was a practice still prevalent among "old order" Mormons, despite polygamy having been banned in America since the 1860s and by the Church of Latter-Day Saints in 1890 (via World Population Review). The clippings Atwood unearthed described how the men, rather than enjoying the experience, often complained of being "run ragged" by going from one wife to the next. Utah, a state famous for its Mormon population, recently downgraded the criminal status of polygamy among consenting adults, ensuring it is now on a par with getting a speeding ticket, according to US News.

Atwood drew on news stories about this to build a world where women's sexuality and fertility was rigorously controlled but men had numerous partners. In "The Handmaid's Tale," handmaids are reassigned to new families whenever they have conceived and delivered a child for a senior family in Gilead. The result is that the men might have many sexual encounters outside of their marriages if it means conceiving more children.

Perhaps tellingly, there's the strain endured by Commander Fred Waterford, the husband of Serena Joy, from balancing the demands of his wife and the affection he increasingly shows for Offred, his handmaid.

18th-century public births

It was common among members of the aristocracy for births to be very public affairs. Often various servants and male courtiers would be present in the room, not just medical staff. The idea was to prevent crafty monarchs from replacing an undesirable child with a more desirable one, particularly a deceased or female child with a newborn male — such as during the Reformation, when there were fears that a male heir to a Catholic Stuart king would keep the succession away from Protestant Hanoverians. Despite such mass observations, the male baby produced by the Catholic wife of King James II was always believed to be a changeling. The king was overthrown later that year (via History).

The website also describes how Marie Antoinette gave birth in front of an audience of 200 people, while the wife of King Louis XIV of France's birthing room was filled with countesses, princesses, and dukes, and a carnival-like atmosphere raged outside. In some cases, it took hours for anyone to notice the mother had fainted. Eventually, Queen Victoria maintained that the presence of the Home Secretary was all that was needed in terms of outside observers in the birthing room. After the birth of Prince Charles in 1948, even this practice was phased out, according to The Guardian.

Births in Margaret Atwood's novel and in the TV series are treated as a sacred ritual and conducted in front of large groups of other handmaidens. Like much else in Gilead, this lack of privacy clearly had a long history.

The imprisonment of promiscuous women

For swathes of the 20th century, it was commonplace for American women to be locked up by the state as part of the "American Plan," an initiative involving the mass incarceration of women during World War I who were regarded as too sexually loose. The aim was to protect American soldiers, considered the most vital part of the war effort, from debilitating sexual infections as well as from prostitutes, who were almost always considered to be the carriers of such diseases. Eventually, the mandate spread to many areas of the country, with local and national officials encouraged to lock up any woman they suspected of prostitution. It went on from the 1910s to the 1990s, as detailed by Time.

The conditions for the women imprisoned under the Plan were often unrelentingly grim. Invasive tests for syphilis and gonorrhea were often carried out by male physicians, and women who tested positive were kept in detention centers and jails surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, where abuse and sterilization were rife and the inmates had ineffective remedies, like mercury injections, forced upon them. Even women who didn't test positive but were considered "immoral" could be detained without due process.

The control of women's sexual impulses, particularly those conducted outside of marriage, through punishment and control is a theme that runs throughout "The Handmaid's Tale." Somewhat chillingly, the rules mandated by the "American Plan" are still on the books in various forms.

The Third Reich's Lebensborn program

The depiction in Margaret Atwood's novel of women being made to procreate with important men in Gilead to reverse declining birth rates was influenced by the Nazi policy of encouraging "racially pure" women to breed with SS officers in the hope of producing "Aryan" children. According to History Extra, falling birth rates in Germany combined with the popularity of "race science" meant that around 20,000 babies were born between 1933 and 1945 to mostly German and Norwegian women who had been selected for the scheme. Women with blonde hair, blue eyes, long legs, and a hips and pelvis broad enough for child-bearing were looked upon with particular favor.

The women who took part were treated to fine food in relaxing and luxurious surroundings, often in settings such as grand castles where they were waited on hand and foot. They were given a week to get to know and choose the SS officer they liked the most. Once the babies were born, the women would never see them or their fathers again. They were made to renounce all claims to their offspring so the children could be raised in state-run homes, ensuring their loyalty to Hitler would be total.

After the war, many of the children endured the stigma of having been a direct product of the despised Nazi regime. Others never learned the truth, as, much like the children born to "fallen" women in Atwood's universe, they were adopted out to other families, with their birth records expunged from memory.