What Being A Kid In The Wild West Was Really Like

The Wild West may conjure up images of cowboys riding horses across a lonesome plain, or perhaps a barroom brawl in a rural, dusty town somewhere. Of course, real history isn't much like the fantastical westerns that have played out on screens big and small. In fact, as Live Science notes, the "wild" West may not have been all that lawless, though the people who lived in the vast regions of the 19th-century American frontier did encounter serious hardships.

Quite a few of those people dealing with the travails of life in the Old West were children. After all, there were plenty of families around, from the many American Indian tribes to the pioneer groups that steadily pushed west. Children were part of the daily life of many communities throughout the frontier, no matter how rural or "wild" such places might be.

But what was it really like to grow up in such a unique environment? Did children of the era face peril at every turn? How did they play? Did they have to go to school? The answers may surprise you. This is what it was really like being a kid in the Wild West.

Many children moved frequently

For children of many cultures in the Wild West, picking up and moving to a new home was a regular fact of life. That was certainly the case for many generations of American Indian children whose tribes moved back and forth across the Great Plains. As per "Frontier Children," native tribes moved to trade, hunt game, harvest other food, and to maintain relationships with other groups across the seasons. Children in tribes such as the Cheyenne, Osage, and Sioux were expected to take part in the task of moving camp. In a similar fashion, children in pioneer families moving from east to west still had to complete their daily chores, despite the long miles of walking and harsh conditions faced on the trail (via "Frontier Children").

While some kids accepted this constant moving or even looked forward to the adventure, others found that this sort of travel could be terrifying. According to "Growing Up with the Country," part of that fear was rooted in the realization that the environment could very well kill them. Kids' anxiety may have also stemmed from uncertainty as they struggled to understand why, exactly, their family was moving away from everything they had ever known. From the sweeping expanse of a nigh-featureless plain to the lightning that lit up the sky above their unprotected heads, the trail held serious frights for some children.

Kids were expected to work

For both families that had settled and those who were still making their way through the rural frontier, it was vital that everyone who could did their part. That included kids, who were often expected to complete chores that may seem daunting to children today. This could include roping cattle, milking cows, weeding the garden, and bringing in the wood for the kitchen fire in the pre-dawn dark, according to The Christian Science Monitor. Girls were hardly excused from tough work, too, and could often be found doing much of the same work as the boys.

But it wasn't the same labor as adults. As "Growing Up with the Country" points out, adults purposefully restricted what kids were allowed to do. After all, some tasks were either too demanding or too dangerous — a toddler could hardly be expected to rope a steer, for instance. When a child of the Wild West was able to help out with more laborious tasks, many reported a sense of pride in contributing to the family's well-being. One girl, Edna Matthews, proudly recalled how her mother and siblings ran the farm by themselves while her father was fighting as a Confederate soldier in the American Civil War.

Wild West kids may have been less worried about gender

With the stresses of frontier life sometimes looming large, less practical social conventions could fall to the wayside in the Wild West. Men who had moved to rural outposts on their own might be obliged to take on traditionally feminine tasks, like cooking and doing their own laundry. Likewise, women could find themselves tasked with the sort of heavy labor that, in other places, might be reserved for men only. As time went on and the Wild West became considerably less wild, many communities saw the old gendered separation of labor return (via the Buffalo Bill Center of the West). People of the Old West might also have presented themselves as someone of another gender to protect themselves or to take advantage of a society that had more things on its mind than enforcing a strict gender binary, as per JSTOR Daily.

These shifting gender roles also applied, at least sometimes, to children. As "The End of American Childhood" notes, frontier life often demanded that someone get the work done. If that meant a boy did "girl's work" such as child care or a girl took on traditionally masculine tasks, then so be it. For a time, at least, the separation between chores meant for boys and girls was very weak indeed.

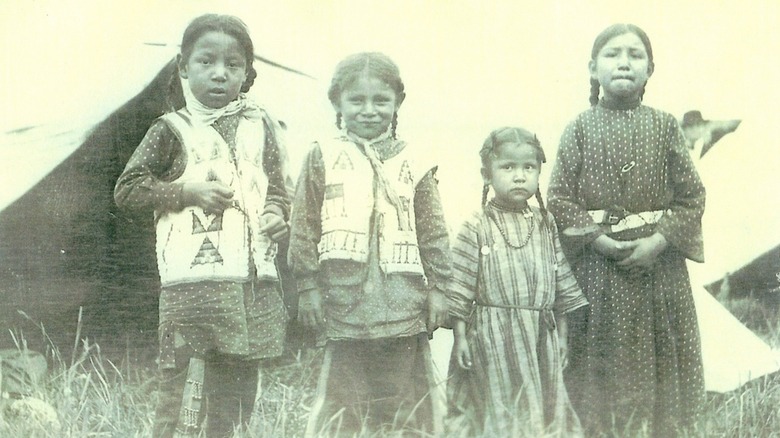

Native children stayed close to home

While pioneer families were claiming land and establishing homesteads throughout the Old West, the truth is that people had been occupying that land for millennia. Before the arrival of white settlers and the increasing restrictions that led to the Indian Wars and the reservation system, many tribes of the Great Plains (like the Sioux, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and more) lived a largely nomadic lifestyle, as per Encyclopedia.com. Pueblo tribes like the Zuni and Hopi were typically more settled by the time of the pioneers. Children were often valued and guided by many members of their community beyond their immediate family.

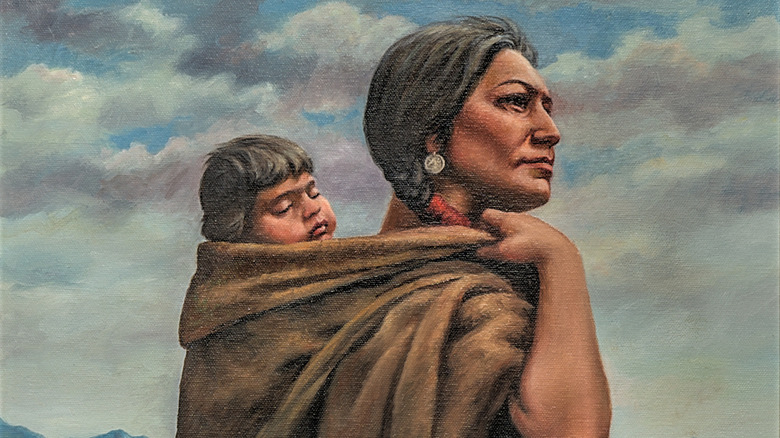

Amongst many of the Plains tribes, very young children stayed close to their mothers for the first few years of their life. According to "Frontier Children," babies could be wrapped up in a cradleboard that was carried on a mother's back. As they grew, boys might expect to gain new names, though that was a less frequent occurrence for girls. Some youths amongst the Blackfeet were also designated as the tribe's "favored child," a pampered, gift-laden scion of a prominent family who might expect to take on the mantle of leadership one day (via "Frontier Children").

Across many tribes, American Indian children were often expected to work as they grew older and take on increasingly complex adult tasks, as well as learn the ins and outs of their expected social roles (via the Journal of American Indian Education). However, physical punishment was a rarity.

Toys could be scarce

Though life in the Old West could be harsh and often required children to do all sorts of work, it wasn't all suffering and drudgery. Children were still recognized as children who should be given the opportunity to play. Of course, there wasn't a big-box store down the street full of plastic toys with bright, flashing lights and recorded music. As The Christian Science Monitor reports, toys in the Old West could get pretty expensive, especially for a pioneer family working with a limited budget. Their children were more likely to take common items of their everyday lives, such as wheelbarrows and sheets, to create their own fun. Imaginative play was also widespread, as were social occasions that attempted to make fun out of food preparation, such as cheese-making parties and an ice cream-like concoction of hot maple syrup and snow.

Native children also had plenty of opportunities for play. According to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, some kids took a loop of string and wove an elaborate version of what we might call a cat's cradle today. Other toys helped to develop hand-eye coordination, like a hoop and dart contraption that sometimes had kids attempting to pass the dart through a rolling hoop. They were also obliged to get creative, such as when Lakota children used spare animal bones to create "bone ponies" that were also used by some settler children.

Schooling was important but access was uneven

Though the structure of life and child supervision in the Wild West may have been seriously different, one thing was all but certain: school. According to Wild West magazine (via HistoryNet), a community couldn't expect to be taken seriously until it had established a schoolhouse, even if it was a humble one-room affair. In fact, one-room schoolhouses were fairly common. Often, it made more sense to ask students to travel a short distance to a small school, rather than a longer distance to a larger, centralized school building.

Even though children living in the Wild West could expect to spend a fair amount of time learning their letters and practicing math problems under the tutelage of the local schoolmarm, it wasn't easy to establish a school. As per THIRTEEN, school teachers — usually just one instructor per school — were expected to manage multiple grades at once. Furthermore, community members were expected to maintain the school, from building desks, to keeping the wood-burning stove going, to feeding and housing the teacher.

But who went to school? Not everyone had equal access, as "Frontier Children" reports. Nonwhite children were sometimes barred from attending school by laws that deemed them "inferior" and unfit to sit alongside white students. Some communities, such as those of Chinese immigrants living in California, gathered together and opened their own schools. And still others, such as the poorest families living in the Southwest, got barely any schooling past what local friars could cobble together.

American Indian children were taken from their families

Some families realized there was a dark and painful side to the frontier educational system. The National Museum of the American Indian notes that the school system established for native children was no charitable enterprise. Instead, the boarding schools that began to spring up throughout the country were meant to obliterate traditional tribal culture. American Indian children, forced to attend, were given English names, made to dress in European-style clothing, forced to practice Christianity, and were continually told that their culture was shameful.

According to National Geographic, the early 19th century saw schools set up on or near reservations. But allowing children to live with their families made assimilation more difficult, so the U.S. government began to fund boarding schools that separated kids from their families. One of the most notorious, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, opened in 1879 and inspired similar institutions in the United States and Canada.

Many children who attended these schools reported serious trauma, ranging from public shaming to physical abuse. Diseases ran rampant through overcrowded schools, and quite a few institutions had dedicated cemeteries for their charges. If some children attempted to run away, schools might even offer a bounty to anyone who brought them back. Though a federal law mandated boarding school attendance for native kids in 1891, many kids and parents fought back. It wasn't until the 1970s that most schools closed, though a small number continue to operate today (via National Geographic).

Kids in the Wild West often faced death

In the Old West, death was simply the final fact of life. However, as "Growing Up with the Country" argues, the mortal dangers faced by children and their families weren't always expected. While some fretted about attacks from American Indians, tribal members could be friendly, while seemingly dangerous wild animals tended to keep their distance. And, despite the gruesome fate of the cannibalistic Donner Party, most settlers managed to keep everyone fed.

Instead, the real danger was presented by illness, which could devastate a young person who grew sick far from a doctor's office. According to "Growing Up with the Country," a drink of stagnant water full of microbes was far more likely to kill someone living in the Wild West than a rattlesnake or a misfiring gun. Children were especially vulnerable to malnutrition, fevers, and dehydration, all of which could have an outsized effect on their small bodies.

The proliferation of disease and lack of clean water led to a seriously grim infant mortality rate. True West reports that, in the 1870s, one in five children would die before reaching their first birthday. However, given that so many people lived in rural places without ready access to doctors, midwives, and record-keepers, the true numbers may never be known.

Asian American children dealt with serious prejudice

The romanticized Wild West tends to be pretty monochromatic. But, as Yes! reports, the true Wild West was far more diverse. Black and Latino people were certainly part of the landscape (in fact, the whole concept of cowboys comes from the Latin American vaquero, says History). So, too, were Asian Americans, who made up about 30% of Idaho's population in 1870. Yet, these people and their children dealt with widespread racism.

According to KNOW: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge, anti-Chinese sentiment grew in intensity after Chinese workers arrived in the United States to work in industries such as mining and the railroad. However, an economic downturn encouraged racism and resulted in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which greatly limited Chinese peoples' entry into the country. Those who were granted admittance had to go through an intense interview process, including children. If they failed to pass scrutiny, kids might be barred from entering, along with their families.

Once living in the U.S., Asian American children of the Wild West often found themselves in an awkward space. Many were pushed to retain their Asian cultural identity by family, but also had to assimilate in order to navigate American society. This left quite a few to feel as if they'd been left out of both cultures (via KNOW). This was in addition to more obvious discrimination, such as when a business openly barred Chinese and other Asian people from entering the premises.

Mixed heritage children had a complicated future

Given that the Wild West could be a pretty diverse place, it should come as no surprise that many people of different backgrounds came together and formed families. But, though a town on the American frontier might have a wide array of people living there and moving through, old racist ways of thinking could still prevail. This meant that the children of mixed-race unions faced a complicated and sometimes bumpy road.

Part of the issue was the social upheaval experienced by many people in the period after the Civil War, as "The End of American Childhood" points out. People moved all about the country, sometimes establishing new families when they still had an old one in their previous home. What's more, antebellum America could sometimes be a convenient place for mixed-heritage relationships. Yet the post-war period and increasing numbers of anti-miscegenation laws made those unions (and the resulting children) inconvenient. Some men simply abandoned their non-white families.

According to "Frontier Children," so-called "half-breed" children of one native and one white parent could be ostracized by both societies, leaving them in a painful in-between space. Some children with prominent parents could escape the worst of it, such as Sacagawea's son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, but few were so lucky.

Many people in the Wild West recognized when childhood was over

Part of the fundamental nature of childhood is the fact that it must end. However, the concept of a transitional state such as the teenage years may have seemed strange to the families of the Wild West. In fact, the whole idea of teenagers wouldn't arise until well into the 20th century, according to TIME. Yet quite a few communities in the Old West recognized that kids did transition to adulthood and held rituals and observances to mark the occasion.

According to "Frontier Children," most kids on the frontier and elsewhere in society were expected to grow up faster than they are today. For white families, this change was only sometimes marked by traditional observances, such as a bar mitzvah for the relatively rare Jewish children (though, as the National Endowment for the Humanities attests, Jewish people very definitely lived and worked in the Wild West). Latino families may have observed something like a quincenañera, with its Aztec roots, though the New York Folklore Society notes that the celebrations we see today have stronger roots in the 1930s.

Around puberty, many American Indian children would find themselves spending more time with adults of their own gender, falling into traditional patterns of gendered work and recreation. Some tribes encouraged them to engage with their impending adulthood by going on spiritual quests, which might involve a journey, fasting, and spiritual rites (via "Frontier Children").