Times Blonde Lied To You

Marilyn Monroe's reputation as an actress and an icon of the mid-20th century has never been untouched by controversy. Famously acidic film critic Pauline Kael dismissed her talent and intelligence in the New York Times, while Peter Bradshaw defended her skills as a comedienne in the Guardian. In their article about her life, the Smithsonian noted the sway she continues to hold over pop culture on the one hand and how obscured the real Marilyn Monroe — born Norma Jeane Mortenson — still is by her public image and the reactions to it on the other.

The Netflix film "Blonde" has attracted a passionate and mixed reception. Ana de Armas won acclaim for her performance as Monroe, but the NC-17 film's overall portrayal of the actress divided critics. Its subjective experience of a tumultuous ride through fame and misogyny was lauded by Variety and Deadline. A similar line of praise was followed by the Guardian, though that review questioned the effectiveness of the film's aesthetic choices and its accessibility to audiences. IndieWire and Collider both felt that "Blonde" was just as exploitative and dehumanizing as the male gaze Monroe is subjected to throughout its nearly three-hour runtime.

Questions about "Blonde's" artistic choices and presentation of Monroe are subjective, a matter for each viewer. Its accuracy to the known facts of Monroe's life — or lack thereof — can be verified. And as it turns out, "Blonde" makes some pretty wild leaps away from fact.

Caveat: Blonde isn't a traditional biopic

For those inclined to judge biopics primarily on their accuracy, it's worth bearing in mind that "Blonde" isn't a biopic in the traditional sense. While all such films are dramaticized tellings of someone's life story, many biopics place at least some emphasis on factual or historical accuracy. Their primary source material, after all, is their subject's life.

"Blonde" isn't directly drawn from Marilyn Monroe's real life and career. Per Vogue, it's an adaptation of the 2000 novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates. And Oates has always maintained that "Blonde" is fiction, not biography. The author deliberately invented characters, changed names, and imagined events to tell a story about the dangers of celebrity in American culture, one that happened to be inspired by Monroe. It's one of Oates' most ambitious pieces of writing, one the New Yorker compared favorably to a mash-up of fairy tales and Gothic fiction while noting the controversy such an approach inspired on the novel's release.

The screenwriter and director who adapted "Blonde" to the screen, Andrew Dominik, was similarly vocal about his priorities with the film ahead of its premiere, and they weren't to do with perfect fidelity to known facts. His focus, he told Vanity Fair, was on how Monroe's childhood traumas affected her perceptions of adult life. "I think that's the fascination about her life," Dominik said. "Seeing the raw trauma in the film humanizes her."

Marilyn Monroe's mother didn't try to drown her

One of "Blonde's" harshest critics has been Charles Casillo, an author and biographer. Like Joyce Carol Oates, he's written a fictionalized look into Marilyn Monroe's life: "The Marilyn Diaries," an imagined journal of the actress'. But Casillo has also written "Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon," which Variety named one of the best biographies written about Monroe. And in an article for AARP, Casillo used his extensive knowledge of the actress to pick apart the historical inaccuracies in "Blonde," starting from the top.

"Blonde" opens with a young Norma Jeane Mortenson (eventually to become Marilyn Monroe) at the mercy of her unhinged mother, Gladys Mortenson. The specter of Norma's father hovers over their relationship; Gladys blames Norma for his absence from their lives. When a potential encounter with this absentee dad is thwarted and Norma starts asking questions, Gladys tries to drown her own daughter. After Norma escapes to the neighbors, she's placed in foster care, and Gladys is committed.

Gladys Mortenson was an unstable person eventually sent to a mental hospital. But according to Casillo, she never tried to kill her daughter in the bathtub. She did once brandish a knife during a breakdown shortly before being committed, but she didn't hate her daughter over her father's absence. There was an attempt made on Monroe's life; her grandmother, ashamed of the baby being born out of wedlock, tried to smother her as a baby.

Marilyn Monroe wasn't a dumb blonde

The most enduring public image of Marilyn Monroe is that of the blonde bombshell, oozing sexuality but completely empty-headed. That image was projected onto Monroe herself by those who didn't know her well. She was aware of this and was unhappy about it. Per the biography "Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon," by Charles Casillo, she sought other types of roles, fretted that she wouldn't find any, and appreciated when men saw past her reputation.

For some critics, "Blonde" is guilty of perpetuating the dumb blonde sexpot image Monroe wanted to shake. It's a complaint the material has faced since Joyce Carol Oates published her book in 2000. The Guardian's Anthony Summers detailed Monroe's intellectual bona fides: devouring Dostoevsky, supporting the civil rights movement, and engaging with a husband accused of communism. He felt Oates, even with the shield of fiction, crossed into libelous territory in its graphic depictions of Monroe's sexuality, in which she has little agency or joy.

Biographer Charles Casillo raised similar objections in an article for AARP about the "Blonde" film. He also took greater issue with how the movie depicted Monroe's intelligence, finding her a stupid puppet dominated by a succession of men. Left out was Monroe's advocacy for abused children, her demands for better material, and the fact that she was one of the first actresses to have an independent production company. "She was used," writes Casillo, "but she was also a master user."

She didn't get a contract after being assaulted

Marilyn Monroe's career is advanced through dark means in "Blonde." While waiting for a meeting for a potential studio contract, she is raped by a studio executive, Mr. Z. After the assault, Monroe is still prepared to go through with her audition but finds she already has the contract. The assault was the "audition."

Mr. Z is a not-so-subtle depiction of Darryl F. Zanuck, the chief of 20th Century Fox. Monroe did have a contract there, and she and Zanuck did not get along, in part due to her willingness to defy him and win significant concessions in the terms of her contract (per Marie Claire). But while Zanuck was willing to bring starlets to the casting couch, there's no evidence he subjected Monroe to it, and none that she was ever raped by him or any other producer, notes the Guardian.

Biographer Fred Lawrence Guiles claimed in "Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe" that Monroe turned down all chances to get ahead in Hollywood through the casting couch, but in her lifetime, Monroe admitted to such experiences. Biographer Charles Casillo argued in AARP that she kept her dignity as much as she could and was not a submissive victim. Casillo noted an incident where notorious Columbia head Harry Cohn tried to get Monroe alone on his yacht. She countered by saying how much she looked forward to meeting his wife. That was the end of that proposition.

There was no threesome with Charlie Chaplin Jr.

The rich and famous being naughty with one another is a well-tapped source of material for writers and filmmakers. "Blonde" posits that, not long after beginning her acting career, Marilyn Monroe tore up the town as part of a threesome, the Geminis, with two scions of Hollywood legends, Charlie Chaplin Jr. and Edward G. Robinson Jr. Their antics are disapproved of by studio chiefs, but more serious consequences come when Monroe gets pregnant by Chaplin. Despite her fierce desire for a child, Monroe gives in to pressure and has an abortion.

There is a grain of truth to this incident. According to biographer Charles Casillo (via AARP), Monroe and Chaplin did have a brief affair in 1948 that transitioned into a lifelong friendship. Monroe was also friends with Robinson, but several years separate when her affair with Chaplin ended and her friendship with Robinson began. The three of them never socialized together, let alone engaged in a notorious threesome with its own name. TIME argues that the affair with Chaplin didn't even register on the Hollywood scandal charts, except as a mild rumor.

Both fact-checks dismiss the idea that Monroe ever found herself in a ménage à trois. And Casillo dismisses the idea that Monroe ever had an abortion. While other authors have speculated she might have done so, including Gloria Steinem (via Women's Health), there is no good evidence for the claim.

Her former lovers never blackmailed her husband

Marilyn Monroe was associated with many high-profile names in her short life, from Elia Kazan to Milton Berle (per People). Among the most significant romances was with retired baseball star Joe DiMaggio, who Monroe met in 1952 and married two years later. The marriage was brief, and "Blonde" depicts it as bleak. DiMaggio is an abusive husband in the film, beating Monroe after he's blackmailed by her former lovers Charlie Chaplin Jr. and Edward G. Robinson Jr., and again after the filming of the iconic scene with the white dress in "The Seven Year Itch."

There is evidence that DiMaggio was physically abusive to Monroe. Fred Lawrence Guiles' "Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe" has at least two recollections of violence, one from a publicist who found DiMaggio's behavior to his wife appalling. Charles Casillo, writing decades later in "Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon," acknowledged the claims but was less sure that the marriage was so vicious. But as Monroe was never in a threesome with Chaplin and Robinson, they could never have blackmailed DiMaggio; that, at least, is indisputably fiction.

Whatever the nature of their marital woes, Monroe and DiMaggio renewed their relationship as friends after the divorce, to Guiles' source's bafflement. Per People, it was DiMaggio who claimed her body and paid for her funeral. And for the rest of his life, he had roses placed at her grave three times a week.

Marilyn Monroe didn't hate being an actress

One of Marilyn Monroe's most famous roles was as Sugar Kowalczyk in the 1959 comedy "Some Like It Hot." It's become one of the most beloved movies of all time, and according to NPR, it helped to finish off what was left of the Hollywood Hays Code. But "Blonde" portrays its production as a miserable experience for Monroe, one that drives her into a mental breakdown and self-mutilation only managed by syringe to the neck. The actress is depicted as disgusted and ashamed of her career as a whole, at least according to Charles Casillo's fact-check for AARP.

"Some Like It Hot" was a difficult shoot for Monroe. By the end of the 1950s, she had developed a dependency on barbiturates and struggled with physical and mental recovery from a miscarriage. Per Variety, she was frequently late or absent from set, struggled to remember her lines, and clashed with Billy Wilder over the interpretation of her character. But she never slashed at her own face, and contrary to "Blonde," Wilder told Cameron Crowe (via Vulture) that the famous "I Wanna Be Loved by You" musical number was shot without fuss.

Monroe's hatred for the film and her career in "Blonde" is also difficult to reconcile with her own statements. Casillo says that she loved "Some Like It Hot" and notes that she consistently claimed during her lifetime that she was happiest when at work as an actress.

There was no Mr. Shinn

Lurking throughout "Blonde" is a certain Mr. Shinn, Marilyn Monroe's talent agent. Shinn arranges her earliest auditions, cultivates her image in the press, and exerts a powerful influence on her private life. Monroe is at times glad to have Shinn as a paternal figure, but he's one of many men to subject her to his lustful advances and his control.

There was no Mr. Shinn in Monroe's life. "Blonde" invented characters and used descriptors or aliases in place of names for some real-life figures, and Shinn seems to be a bit of both. Aspects of him reflect Monroe's real-life agent, Johnny Hyde. He came upon her when she was posing for photographer Bruno Bernard, according to an interview with Bernard's daughter Susan Bernard (via Palm Springs Life). Instantly smitten, Hyde became her agent and supervised the cultivation of Monroe's public persona. He got her an early part in "The Asphalt Jungle" and negotiated her contract with 20th Century Fox even after suffering a heart attack.

Hyde's interest in Monroe was not strictly professional. He was so stricken by her that he left his family, hoping to persuade Monroe to marry him, according to Fred Lawrence Guiles' "Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe." But Monroe refused, telling Hyde that she loved him but wasn't in love with him. Hyde died in 1950 with that tension between him and Monroe, but per Donald Spoto's "Marilyn Monroe," she remained grateful to him for the rest of her life.

The Kennedy affair is greatly exaggerated

It's a piece of Hollywood legend, part of the mythology around the Camelot era of America: the affair between President John F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. Her sultry and widely imitated rendition of "The Birthday Song" at a gala at Madison Square Garden (via YouTube), only months before her death, only fueled reports that the two were romantically involved. "Blonde" takes those rumors and spins them into a dark encounter of sexual assault, after which Kennedy heartlessly discards Monroe.

There is no proof that Kennedy ever assaulted or coerced Monroe, and the presence of that scene in Joyce Carol Oates' novel led Anthony Summers to call the book historical libel in the Guardian. Even more benign imaginings of their affair have limited factual ground to stand on. In his biography "Marilyn Monroe," Donald Spoto concluded that the evidence only supports them meeting four times and having sex once. Her friend Ralph Roberts claimed that, from the way Monroe described the night to him, it wasn't a momentous event in either of their lives.

Biographer Charles Casillo disagreed. In his fact-check of "Blonde" for AARP, he said that Monroe did attach great importance to her relationship with Kennedy, far more than he did. When Kennedy withdrew from contact with Monroe, it affected her greatly and contributed to her despairing state of mind in the last months of her life. But Casillo considered the film's imagined assault groundless.

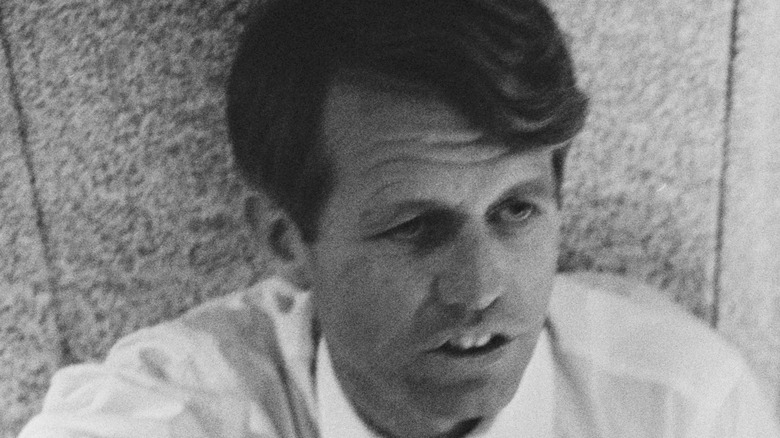

Robert Kennedy didn't kill Marilyn Monroe

Whatever the extent of Marilyn Monroe's relationship with President John F. Kennedy, it remains one of the most famous of her affairs. Less well-known are rumors that she carried on with the president's brother, Robert F. Kennedy, at either the same time or immediately after her dalliance with John. The possibility that Monroe slept with both Kennedy brothers, and inconsistencies in the reports about her death, have fueled conspiracy theories that Robert Kennedy was somehow involved in killing Monroe.

The Telegraph detailed a version of this theory ahead of "Blonde's" release, wherein Monroe's threats to reveal the affairs to the press led Robert to personally poison her. There's no such scene in the movie; Monroe overdoses on barbiturates, her given cause of death. But in Joyce Carol Oates' novel, an assassin hired by "RF" delivers a fatal injection to Monroe while she sleeps.

More than anything else in the novel, the insinuation against Robert Kennedy upset The Guardian's Anthony Summers. Years before "Blonde" was published, biographer Donald Spoto rejected the idea that they ever had an affair in his book "Marilyn Monroe." But another biographer, James Spada, does think the affair happened. He suggested to People that efforts to cover up their relationship, and the affair Monroe had with the president, were misconstrued as a cover-up for murder by some observers.