The Moment Of Death Isn't As Clear As You Might Think

Many philosophers argue that what makes human beings different from other animals on Earth is our awareness of death; our knowledge — which generally emerges at an early age — that one day our bodies will stop working and our lives will all come to an end. And though it's unclear how much people imagine the scene of their own demise, the moment of death is familiar to us today from movies and TV, with even children's cartoons representing death as an exact moment when dotted pupils are replaced by 'X's on each eye.

However, the mystery around the exact moment of death has long fascinated curious poets, whose stock-in-trade is uncertainty and whose minds naturally shine a light on the ungraspable. Take Edgar Allen Poe for example, who seemed to intuit that the moment of dying isn't as clear-cut as many of us assume when he mused: "The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?"

Despite the clarity with which popular culture tends to treat the moment of death, artists and thinkers have been skeptical about whether the moment of death really does occur in an instant as we tend to believe. As the professor of philosophy, William J. Gavin, highlighted in a study of death in the works of Plato in 1974, while death as an abstract concept is measurable — by the absence of a response on an echocardiogram, for example – dying as a process is a trickier thing to define ... as recent scientific developments have shown.

The changing definition of death

Though we tend to think of death as a fixed moment in time when a life is definitively at an end, the exact criteria by which death is observed to have occurred has changed through the centuries, as medical science has advanced and as we have developed a better understanding of the complex processes which underpin animal life on Earth.

Writing in Scientific American, Christof Koch, a neurophysiologist and computational neuroscientist who is also president of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, traces the changing definition of death down the ages, noting that at one time the absence of a pulse, indicating heart failure, was the empirical evidence that a person was dead. Yet the development of technology to detect and analyze brain signals has meant that medical practitioners now refer to these criteria to decide whether a person is in fact medically dead. Meanwhile, technology has allowed humanity to perfect techniques by which those two are unable to breathe for themselves or whose heart has stopped may be given life support until they can be successfully revived.

That science that has blown wide open many of the assumptions the western world has had around the concepts of death and dying is highlighted by Koch in this article's highly provocative title, which simply asks: "Is Death Reversible?" While death may not exactly be curable in the 21st century, recent research has cast doubt on how we define death even today.

An hour window?

Christof Koch's question comes at a time when brain death, the prevailing metric by which a person is deemed to be deceased, is coming under scrutiny like never before, raising fresh questions about the nature of death and dying.

An article presenting the findings of one major experiment to undermine modern beliefs around the moment of death and how to define it appeared in the science journal Nature in 2022. Titled "Cellular recovery after prolonged warm ischaemia of the whole body," the article shared the latest work from a team of scientists based at Yale University who worked with the organs of dead pigs. They found in certain conditions the pigs' brains could essentially be reanimated up to an hour after they had been slaughtered.

Lead scientist on the study Dr. Nehad Sestan confirmed the findings and the repercussions of the experiment during a press conference, explaining: "These cells are functioning hours after they should not be ... this tells us is that the demise of cells can be halted. And their functionality restored in multiple vital organs. Even one hour after death," via CNN. The research offers the tantalizing prospect that the potential to reactivate organs previously considered dead — including the brain.

As Koch remarked on the publication of previous work from Sestan and his team, the continued presence of working neurons in 'dead' brains means that future potential to revive people who have been found dead by essentially "rebooting" the brain "cannot be ruled out."

There may be consciousness after clinical death

Such findings as those shared by Dr. Nehad Sestan et al undoubtedly raise profound questions about how society defines death itself, and how future technology should be ethically employed for the good of humankind. As Christof Koch notes in Scientific American, to resupply consciousness to brains that had previously been decapitated — such as those of the pigs used in the Sestan experiment — would surely raise moral questions around the suffering of the creatures in question and the potential trauma they would surely endure.

Meanwhile, wide-ranging studies such as those conducted by Professor Sam Parnia, director of the Human Consciousness Project at the University of Southampton in the U.K., have found that consciousness seems to continue minutes after patients have been declared clinically dead, suggesting that the memories during near-death experiences reported by those whose hearts have stopped may have some grounding in scientific fact. Currently, the definition of death used in the western world today is evolving just as it was before medicine turned to brain death as the primary metric to measure the cessation of life.

Zombie genes

As scientific research continues into what exactly happens in the brain as we die, findings repeatedly undermine the popular conception of the moment of death as a precise split-second occurrence. And as it does so, experts in the field of medical ethics come face-to-face with moral conundrums arising from the discovery of uncanny or otherwise spooky phenomena.

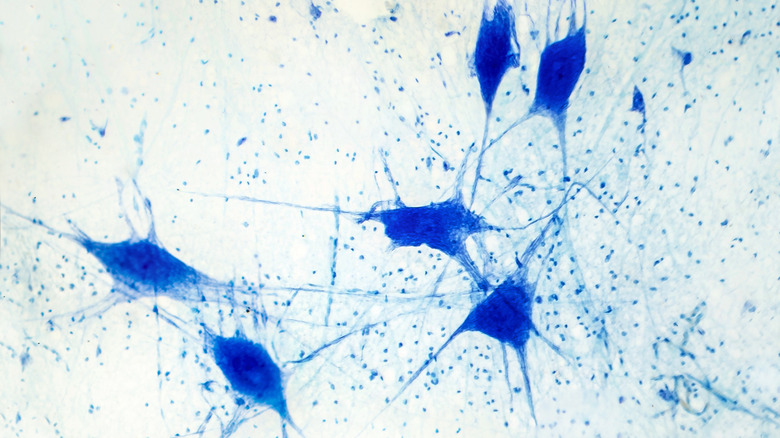

Take for instance the findings published in the journal Scientific Reports in 2021 of an experiment observing the behavior of genes in the human brain in the hours after death. As reported in UIC Today, certain genes in the human brain found in glial cells, actually increase in function thereafter, attracting the nickname "zombie genes" after the findings came to light. "That glial cells enlarge after death isn't too surprising given that they are inflammatory and their job is to clean things up after brain injuries like oxygen deprivation or stroke," said Professor Jeffrey Loeb, one of the authors of the article who explained that the idea that the brain fails to function at the moment of death was far too simplistic. "Most studies assume that everything in the brain stops when the heart stops beating, but this is not so[.]"

The Brain Death Project

Amid the ever-expanding possibilities of medical science to revive living creatures that in years past would simply have been considered dead, there is increasing uncertainty around how medical professionals should approach the duty of declaring patients clinically deceased. Because of this, prominent figures from the world of neurology and end-of-life care, such as Associate Professor Gene Sung, the Director of the Neurocritical Care and Stroke Division at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles are working on how to ethically deal with this uncertainty.

Sung, who is also a committee member of the World Brain Death Project, which seeks to provide greater alignment among doctors around how death is defined in a medical setting, said, "This is one of the most basic parts of being a physician — who's alive? who's dead? How does one make these determinations, and how do you tell family members their loved one has died?" Sung explains. "That's why I started this project — we still have some difficulty in dealing with and understanding these problems" (via USC).

However, Sung's goal is not just to ensure medical practitioners can be sure a brain is dead when they say it is. Per the same source, the World Brain Death Project also seeks to reconcile medical definitions with the cultural practices and religious beliefs of those receiving end-of-life care, and those of their loved ones who understandably care that the patient in question is being properly cared for when they die. And as technology advances, it seems the moment of death may grow even trickier to pin down.