The Story Of The New York Building That Inspired The Eiffel Tower

If you keep random factoids in your brain in case a game of Trivial Pursuit should break out at any moment, you might know that the Tower Building, built in 1889, was New York City's first skyscraper, as PBS explains. Or... was it? That depends on what you think counts as a skyscraper, but what is not up for debate is that the city had a very tall structure over three decades earlier.

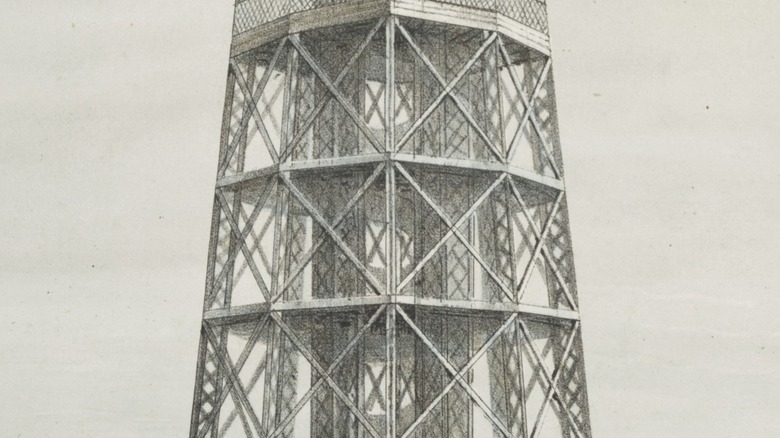

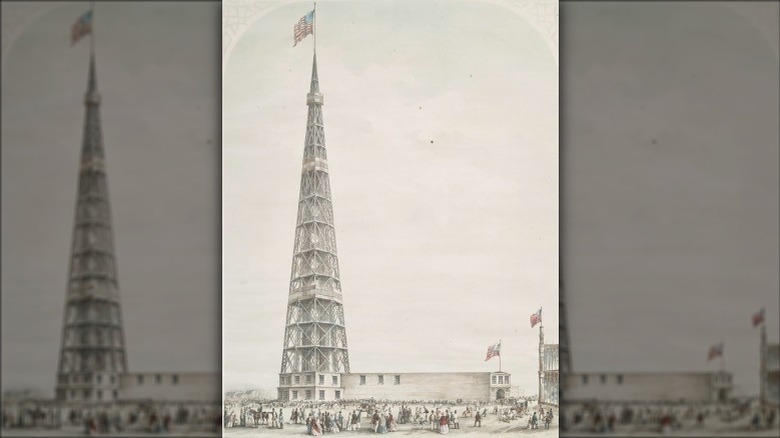

The Latting Observatory was built in 1853 and was taller than anything seen in the city before. According to the 1854 work "Francis's New Guide to the Cities of New-York and Brooklyn, and the Vicinity," it was an octagonal-shaped building built of wood and stone, held together with iron beams.

But if it was the first of its kind, what happened to it? And why do so few people even know it existed? This is the untold truth of the Latting Observatory, the forgotten building that inspired the Eiffel Tower.

The 1851 Great Exhibition in London

The Latting Observatory's story starts long before the structure was even a twinkle in its creators' eyes. To discover the reason behind this building in New York City in 1853, you have to go across the pond to England two years previously. It was the Brits who started the "World's Fair" era in 1851 with The Great Exhibition in London, according to Britannica. Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, who was intelligent and curious but had virtually no responsibilities to take up his time, was very hands-on in the event's planning. Town and Country even calls it "Prince Albert's Great Exhibition," although most people would refer to it as the Crystal Palace Exhibition, for its centerpiece building. To be fair, the V&A notes that Henry Cole, who was later knighted, deserves just as much if not more credit for the exhibition.

The idea was simple: Get the best of cutting-edge science and industry from around the world (but especially Britain and its colonies) and exhibit it all together. This would inspire British inventors, educate the British public, and encourage the purchasing of British products by foreign countries.

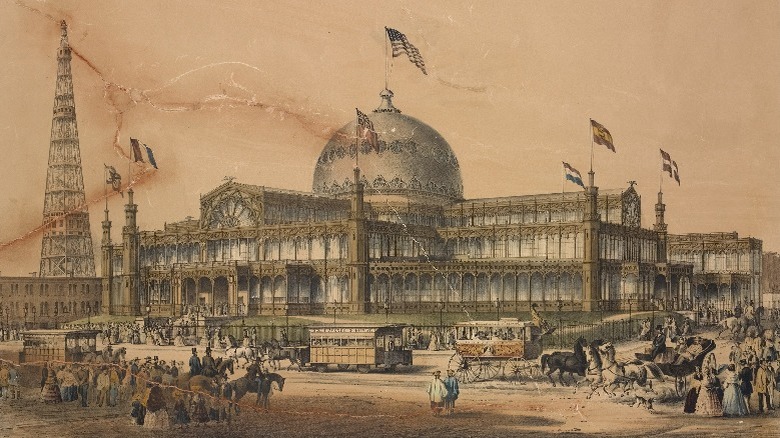

By any metric, the exhibition was a massive success. In the five and a half months it was open, 6 million people, or about 1/3 of the population of the entire country, visited the 100,000 exhibits in the stunning temporary structure – the Crystal Palace (pictured) – purpose-built for the event. It made so much money for science and art education that its effect on funding scholarships is still being felt today.

The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations

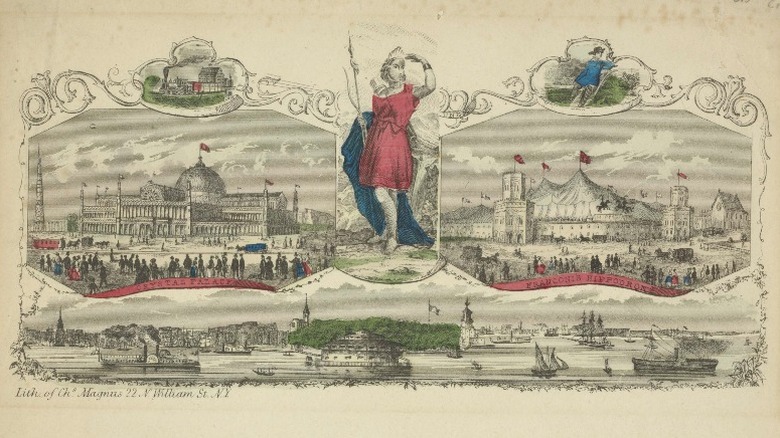

The Great Exhibition in London was a huge success in almost every way. But it had been in England, and maybe a young, upstart country that had only gotten their freedom from them 75 years before couldn't help but want to show they could put on their own cool exhibition, so there! It was this New York City-based rip-off of the British event, held just two years later, and which would be known as The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, that the Latting Observatory (pictured far left) was actually built to take advantage of.

New Yorkers were not the only foreigners to copy the Brits. According to Britannica, over the next 35 years, there would be dozens of imitators held around the world. However, America's first attempt wasn't subtle, as they built their own Crystal Palace (pictured center) for their exhibit, which meant it was colloquially called the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition. The exhibits inside the Crystal Palace in Bryant Park were also very similar to what visitors to the London version would have seen. The biggest original addition inside was an extensive display of sculptures.

But outside the Crystal Palace, there was something much different. Something that was completely and unequivocally original: The Latting Observatory. Stretching to the sky just outside the exhibition hall, it was a modern marvel. And although it was a private financial venture, because it was right there and built at the same time, everyone assumed it was an official part of the exhibition.

Who was Latting?

The Latting Observatory was such an unusual and eye-catching structure for its time that people in New York City believed there was only one guy who could have thought it up. "Almost everyone has named this Barnum's Tower, under the belief that the great showman is at the bottom of it," the 1854 work "Francis's New Guide to the Cities of New-York and Brooklyn, and the Vicinity" stated. "But such is not the fact: Mr. B. has no special interest in any of affair [sic] of public entertainment in the City except the American Museum."

In reality, Waring Latting came up with the idea and design, yet he was considered so un-notable that if he was mentioned at all in contemporary accounts, it was usually just his name and no extra information about the man. So unimportant was he that "Francis's New Guide" even gets his name wrong, calling him "Warren Latting." We do know he didn't design it for any lofty reasons, and the observatory wasn't even an official part of the exhibition. Instead, he was simply looking to make a profit off the event, which was expected to be a huge financial success like the London version.

Latting didn't stop getting involved in notable building work after the observatory. The Library of Congress has a letter Latting wrote to President Abraham Lincoln in 1864, informing him that "a number of patriotic citizens [have] organized themselves into an association for the purpose of erecting a suitable Memorial to our brave soldiers" and asking the (assumedly pretty busy) commander-in-chief to attend an upcoming meeting of the group.

The Latting Observatory was the tallest building in North America

These days, New York City – specifically Manhattan – is synonymous with huge buildings stretching to the sky. So it's difficult to comprehend just how tall the Latting Observatory would have seemed to people in the 1850s. Back then, the tallest building on the island, according to The New York Times, was Trinity Church. The church's spire reached an impressive 290 feet, although while it might have reminded worshippers to look to the heavens in awe, it wasn't like people could get to the top and have a look around. It was decorative height, not functional height.

The Latting Observatory, on the other hand, had height that was built to be put to use, not just look pretty. Contemporary accounts give different heights for the finished tower, although most agree it was at least 300 feet, possibly as much as 315. Some reports, including one in The New York Evening Post (and reprinted in the Southern Weekly Post), said it reached 350 feet.

The result was a lot of very scared people, who were convinced the thing could not be safe. Per a 1930 article in The New York Times citing contemporary reporting on the building of the Latting Observatory, so many New Yorkers were convinced that something so tall would be a death trap that extra inspections were undertaken, and an outside architecture firm released a report on it. The final conclusion on the building was that it would "be perfectly safe for the purpose for which it [was] designed."

The building's elevator was a modern marvel (maybe)

The introduction of what was essentially a skyscraper meant people had to find a way to get up to the top. And while the population might have been fitter in those days, all those stairs were still not fun. A New York Times reporter who made the trek reported, "The ascent is a little fatiguing, but it aids the digestion" (via "From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators").

Other publications were quick to reassure their readers that one didn't have to suffer so much to get to the top ... if one was brave enough. A newfangled contraption, the elevator, would be installed in the Latting Observatory. "At distances of 100, 200, and 300 feet, passengers will be lifted by a steam car to landings," Scientific American explained. The New York Times expanded on this description a bit, writing, "A well 15 feet in diameter will be carried the whole way up, through which personas will be hoisted to the different landings." For those who didn't like the sound of that, though, "There will also be a spiral staircase." But there was no need to fear, The New York Mirror promised (reprinted in the Natchez Daily Courier), since, in the elevator, one could "sit in ease and safety, and be gently raised by steam power to the highest apartment."

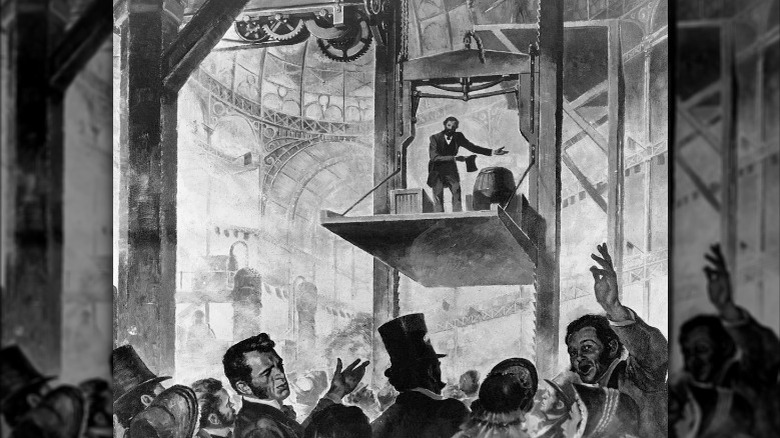

However, while Elisha Otis definitely demonstrated his elevator in the neighboring Crystal Palace exhibition center (pictured), "From Ascending Rooms..." believes there's reasonable doubt these elevators were ever actually installed as promised in the observatory.

The view was incredible

If you had quite a bit of spending money lying around, you could hop on a plane to Dubai tomorrow, look out the window from 40,000 feet in the air, and then once you landed, go to the Burj Khalifa and take some very fast elevators up to the observation deck on the 148th floor. With heights like these a regular part of the world now, the height of the Latting Tower can only seem a bit ... unimpressive. But for those individuals who had quite literally never seen the world from that angle before (unless, for some reason, they had been up in a hot air balloon), it would be closer to modern people going up in a spaceship and seeing Earth from that vantage point.

There were three observation platforms on different levels of the building, the third being near the very top, according to The New York Times, where there were telescopes installed. "On the most elevated floor will be placed a superior instrument, which will afford a clean, and, we need not say, most impressive view, commanding over land and ocean, bay, and river, of 50 of 60 miles!" The New York Mirror exclaimed (reprinted in The Democrat). People had never seen anything like it, and contemporary reporting focused heavily on the panoramic view.

Even decades later, according to The New York Times, people were still amazed enough by the view to pay $75-100 in 1912 money for a copy of the most famous etching of the vista (pictured).

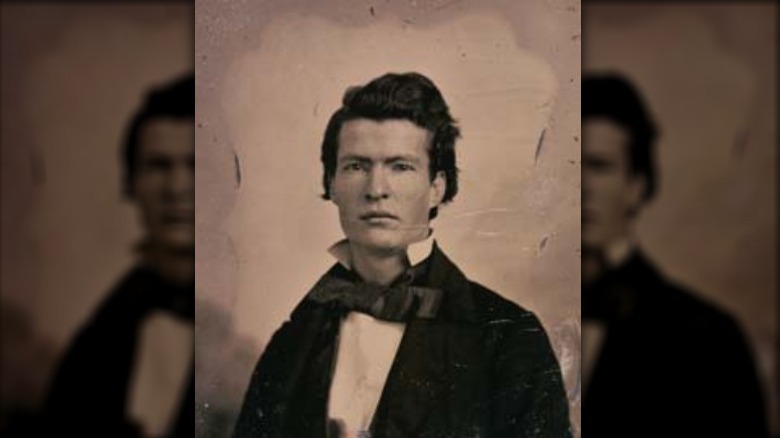

A young Mark Twain was impressed by the observatory

While Samuel Clemens (pictured in 1851) undoubtedly wrote letters, notes, and stories as a child, none of that juvenilia survives, according to "The Letters Of Mark Twain, Volume 1, 1853-1866" (via Project Gutenberg). The first writings in his hand that historians have discovered are from a trip he took around the U.S., including to New York City, in the summer of 1853, right at the beginning of the 16-month run of the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. So it's certain that the 17-year-old Clemens not only saw the Latting Observatory but also wrote to his sister about it in the earliest letter of his known to still exist.

While it only merited one line, the future Mark Twain approved of the record-setting structure, writing, "The Latting Observatory (height about 280 feet) is near the [Crystal] Palace — from it you can obtain a grand view of the city and the country round." However, this astonishing building was not as impressive to him as another of New York's marvels: "The Croton Aqueduct, to supply the city with water, is the greatest wonder yet."

After the fair failed, the Latting Observatory became a tourist attraction

The 1851 Great Exhibition in London had been a complete triumph and a source of national pride. The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City ... was not. If the goal of the U.S. in putting on their own exhibition was to show they could do it better, then they categorically failed. "America's Industrial Exhibition, which was to eclipse royalty, is nothing more than a Wall Street stock jobbing enterprise," the Alta California newspaper reported in August 1853 (via "The Finest Building in America: The New York Crystal Palace, 1853-1858"). Britannica writes that the exhibition's investors lost a ton of money.

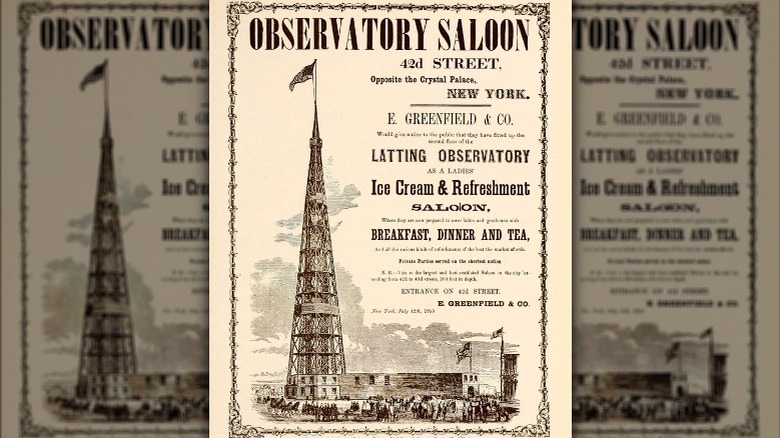

Still, New York was a busy place, so there was no reason a unique building like the Latting Observatory couldn't succeed as a tourist attraction. A handbill from the time (pictured, via the Bard Graduate Center) informed the public that the second floor was now a "Ladies' Ice Cream & Refreshment Saloon." You could enjoy any meal of the day there, and even hire it out for private parties.

But the Latting Observatory would only last as a tourist attraction a little longer than the exhibition itself. Despite its record-breaking height and amazing view, it also failed to make money. It was sold to a marble company that used it for storage, according to "From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators," and they ruined the one thing that made it unique by removing the top 75 feet from the building.

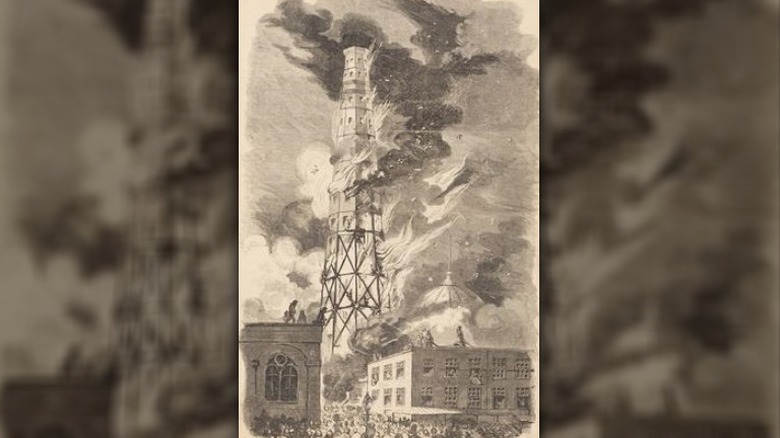

The Latting Observatory was destroyed in a fire

On August 30, 1859, a fire in a shop spread to nearby buildings, and soon the mostly-wooden Latting Observatory was engulfed in flames. The destruction of the observatory might have been its most popular day ever, considering The New York Times had a reporter on the scene who wrote that "the spectacle drew together an immense number of spectators from all parts of the City." The author of the 1885 work "Reminiscences of the Old Fire Laddies and Volunteer Fire Departments of New York and Brooklyn" wrote that the conflagration of the observatory "presented one of the grandest spectacles imaginable." And The Pittsfield Sun reported (via "The Finest Building in America"), "A sheet of flame perfectly white extended from the bottom to the top of the building ... a fearful but brilliant sight to the thousands on the ground."

A 1912 article in The New York Times quoted an extremely vague source explaining contemporary feelings after the fire, writing "it was said at the time" that "the destruction of the observatory is a loss to the city. The stranger will no longer be enabled to take in at one glance this great metropolis, but must be content to view it in sections at much trouble and expense."

The Crystal Palace also caught fire but was saved (until a different fire destroyed it a couple of years later). The New York Times reported that more than a dozen buildings were destroyed, adding up to $150,000 worth of damage. After the fire, no taller structure would be built in New York City until the New York World Building in 1890, per New York YIMBY.

Most people forgot the building had ever existed

Even though the Latting Observatory was literally the tallest building in America, even though it was arguably Manhattan's first skyscraper, people almost immediately forgot about it. But in a time when the news was much more localized, it's perhaps understandable that those outside New York City didn't long remember a building they had only read about in the newspaper a few times. What is more surprising is that the entire city of New York also got collective amnesia, like the Mandala effect, but with the result of wiping a memory completely rather than just misremembering.

A 1912 article in The New York Times opined that "probably few even of the oldest inhabitants remember ... the famous Latting Observatory." One year later, a Brooklyn paper, the Times Union, proved this fact when a letter to the editor asked when the observatory (no name given) and the Crystal Palace burned down. As the writer's chosen nom de plume was "39 Years Reader," one would assume they were not particularly young and had lived in the area for at least four decades, yet they did not know this information. Nor, however, did the newspaper's editors, who were able to supply the year for the destruction of the Crystal Place, but after "a careful search," could find no information on the observatory (which, again, was not named).

By 1930, a tidbit on the Latting Observatory being New York's first skyscraper was syndicated in newspapers across the country as a fun "did you know?" fact for readers. The expectation was that, no, they did not know. The building had been forgotten.

The Latting Observatory inspired the Eiffel Tower

Looking at images of the Latting Observatory, you probably can't help but notice that it bears a bit of a resemblance to a much more famous tower. And if you don't know when the Eiffel Tower was constructed, you might assume the New York building was simply a bad attempt to copy the famous French one and bring a bit of Paris sophistication across the pond.

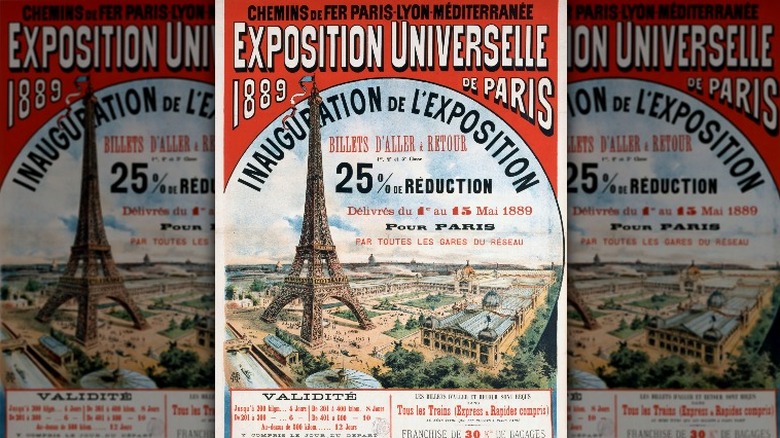

But it was actually the other way around: The Latting Observatory was an influence on the construction and design of the Eiffel Tower, which was dreamed up three decades later for a Paris world's fair. The eponymous engineer of the latter structure admitted this himself, according to an article in the 1889 volume of "Engineering News and American Railway Journal," which stated that Gustave Eiffel "acknowledges that the original idea of a 1,000-ft. tower was borrowed from America."

Not that the publication was willing to defend the Latting Observatory's looks over the beautiful Eiffel Tower. The same article called the observatory "simply a well-braced 'observation mast,' rising from an extremely ugly base, built without regard to beauty or form..." The author did not feel the same way about the Eiffel Tower, however, writing it is "in itself a thing of surpassing grace and the one great decorative feature of the most successful world's fair ever held."

The Latting Observatory also inspired some less-famous architects and inventors

While being (arguably) the first New York skyscraper, influencing the design of the Eiffel Tower, and getting the seal of approval from Mark Twain would be enough bragging rights for any edifice, the effects of the Latting Observatory's brief time in existence had even more far-reaching effects than that.

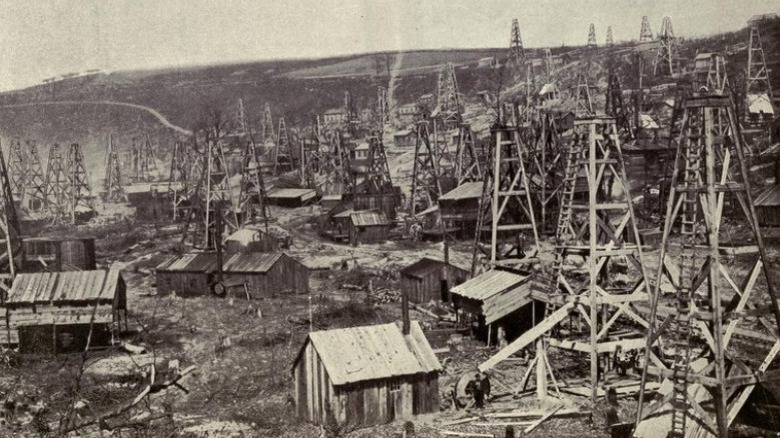

If your first thought on seeing the observatory was that it was a dead ringer for an oil derrick, you were right. George Henry Bissell was a lawyer practicing in New York City when the Latting Observatory was constructed, according to "The Finest Building in America," and within a couple of years, he'd invented the remarkably similar-looking oil derrick and erected some in Pennsylvania (pictured). He also had a friend who shared his interest in the possibilities of oil, and that guy was involved with the Crystal Palace Association. There's almost no way Bissell wouldn't have been familiar with the observatory, and his invention was clearly influenced by the design.

Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes was born almost a decade after the Latting Observatory was destroyed by a fire. But according to the biography "Love, Fiercely: A Gilded Age Romance," which chronicles his life and marriage, the boy who would grow up to become an architect, collector of maps, and a renowned expert on New York City's geographic history was "obsessed" with his copy of the etching of the view from the top of the observatory. Considering the interests he chose to pursue as an adult, it's not a stretch to say that image inspired his whole career.