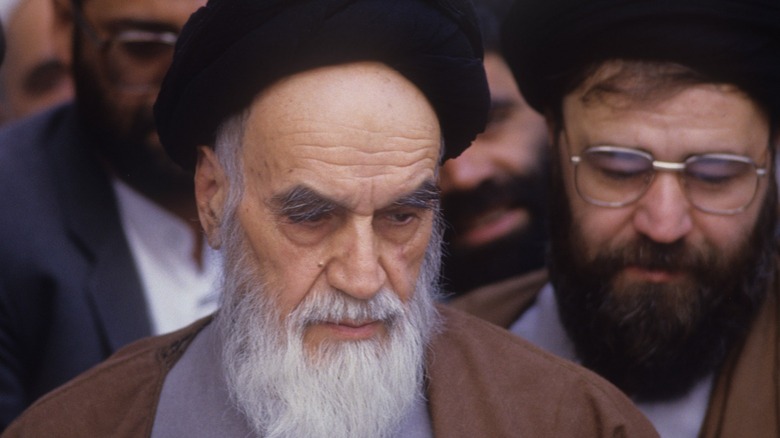

Essential Facts About Ayatollah Khomeini

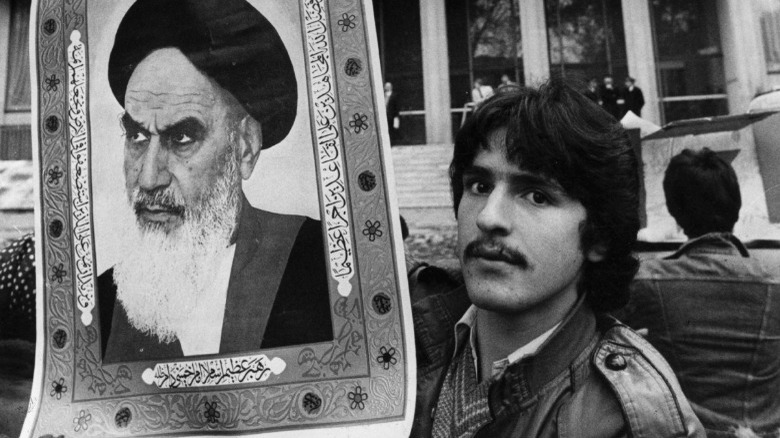

Among the most infamous political and religious leaders of the 1980s was former grand ayatollah of Shīʿa Islam and head of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ruhollah Khomeini. As The New York Times reported upon his death, Khomeini was born in the early-1900s in Khomein, Iran, the son of an Islamic religious leader. His father was murdered in a dispute when Khomeini was still a kid, but he still continued to grow up studying Shīʿa Islam.

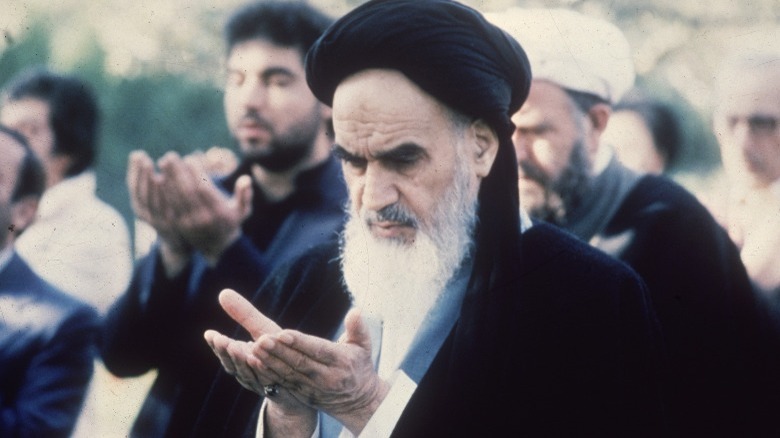

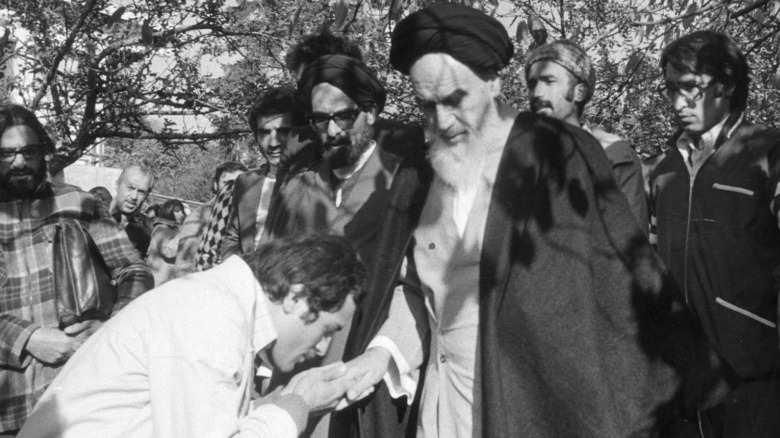

By 1962, Khomeini had progressed far enough in his religious and legal studies and teachings to become the grand ayatollah in Twelver Shīʿa Islam. In Twelver Islam — by far the most dominant Shīʿa sect within Islam — ayatollah is a term reserved for only the most learned and respected of religious scholars (per Juan Eduardo Campo in "The Encyclopedia of Islam"). The highest ranking ayatollah is known as the grand ayatollah or "supreme leader." They are said to be representatives of the Hidden Imam (Muhammad's successor) in Twelver Shīʿa Islam, and as such are highly influential in the religion.

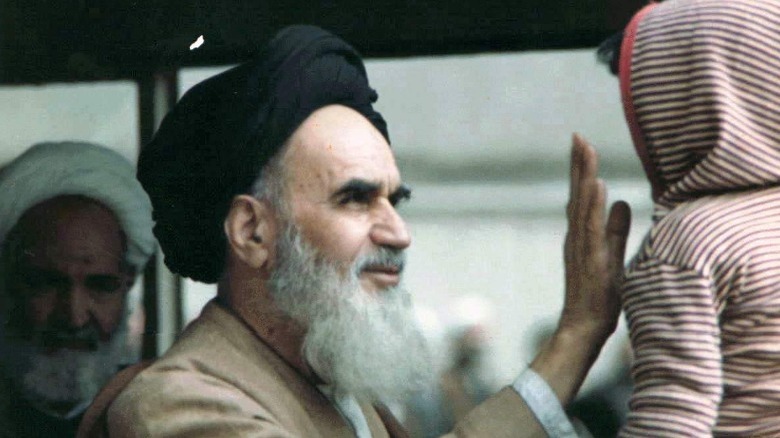

After taking power in Iran, former Grand Ayatollah Khomeini was one of the biggest critics of American foreign policy, and he referred to the United States as the "Great Satan" of the world, notes the Times. Khomeini ruled for almost 10 years as the supreme leader of Iran until his June 1989 death. A notoriously private and illusory figure, this is the untold truth of Ayatollah Khomeini.

He was a political dissident under the Shah

For the majority of his life, not only was Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini outside of the government, but for much of it he was also a serious political dissident. As James Bill explains in "The Eagle and the Lion," after President Dwight. D. Eisenhower helped plot the overthrow of the Iranian government under Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 (via NPR), Mossadegh's picture became a symbol of opposition in Iran to the corrupt shah. In the early 1960s, the Iranian people's disaffection with him led to widespread political protests among teachers, and after the death of Ayatollah Muhammad Hussein Burujirdi, the religious classes became politicized, too.

To try and maintain his hold on power and mollify the masses of Iran, the shah instituted the "White Revolution" in early-1963. It was designed to ease tension by allowing for women's enfranchisement, improvements to literacy, and economic benefits for the working class. However, the White Revolution was not very popular in Iran, and especially with a young Khomeini.

Khomeini was a religious successor to Ayatollah Burujirdi upon his 1961 death, and he spoke out forcefully against the White Revolution many times. After giving a speech criticizing the shah on the sacred Shīʿa Islam commemoration of Ashura, Khomeini was immediately jailed. This incident boosted Khomeini's popularity among the shah's opposition and the religious classes. It also firmly entrenched him and other religious scholars as the leaders of anti-shah opposition in Iran, turning them from religious to political leaders.

Ayatollah Khomeini was exiled from Iran in 1964

After the implementation of the White Revolution and arrest of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1963, the following year the Iranian Majlis (parliament) approved an incredibly controversial law. Known as the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), the law gave all Americans in Iran who were working for the United States' government complete diplomatic immunity, according to James Bill in "The Eagle and the Lion." The law was not limited to just employees of the government but also their families and dependents with them.

Basically, Americans were no longer subject to Iranian courts or laws like Iranian citizens were. Among the outraged were Khomeini, who issued one of the most important political speeches in modern Iranian history on October 26, 1964. Khomeini firmly came out against SOFA, arguing that American cooks could now murder Iranian religious leaders with impunity, and he chastised the government for their secrecy surrounding the agreement.

Khomeini also claimed that the agreement meant that an Iranian who ran over the pet of an American would be subject to more legal consequences than an American who murdered the shah. Less than a month later, Khomeini was exiled to Turkey. He soon made his way to Najaf, Iraq, where he stayed for 14 years until moving to Paris, France, in 1978 (per William L. Cleveland in "A History of the Modern Middle East"). Khomeini did not return to Iran until February 1979, almost 15 years after his initial exile.

He was an influential author

While Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was living in Iraq from 1964-1978, he became a very influential author within Shīʿa Islam. In 1970, he published what is probably his most well known and prominent work, "Islamic Governance." As the Tony Blair institute for Global Change explains, "Islamic Governance" was a book that established the powerful concept of "vilayet-e faqih," which means "guardianship of the Islamic jurist" in Farsi.

The concept of vilayet-e faqih outlined by Khomeini is the creation of a state where Shīʿa Islam scholars, such as ayatollahs and grand ayatollahs, would form and control the government. The government would be based on Shīʿa Islam ideology, with the Shīʿa interpretation of the Sharia forming the basis for its jurisprudence. A supreme leader, or grand ayatollah, would be in charge of the government and only beholden to God. Khomeini was the creator of this ideology, and "Islamic Governance" was the prelude to the post-Iranian Revolution government of Iran.

Khomeini wrote more than 200 other works during his life, and many of them were officially published on the internet by the Iranian government following his death (via the BBC).

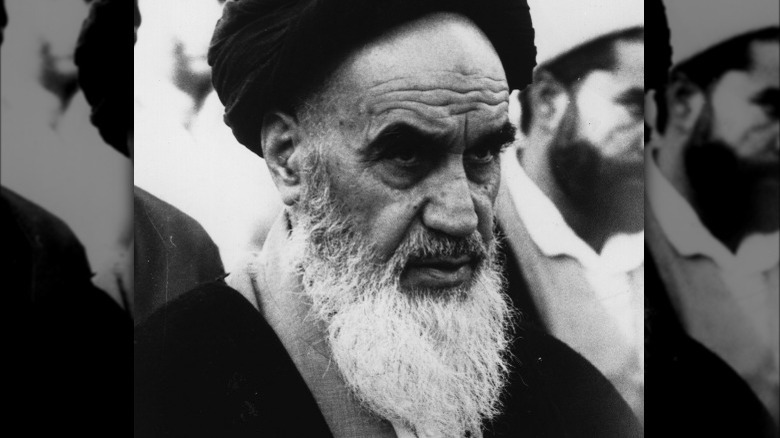

He took power following the Iranian Revolution

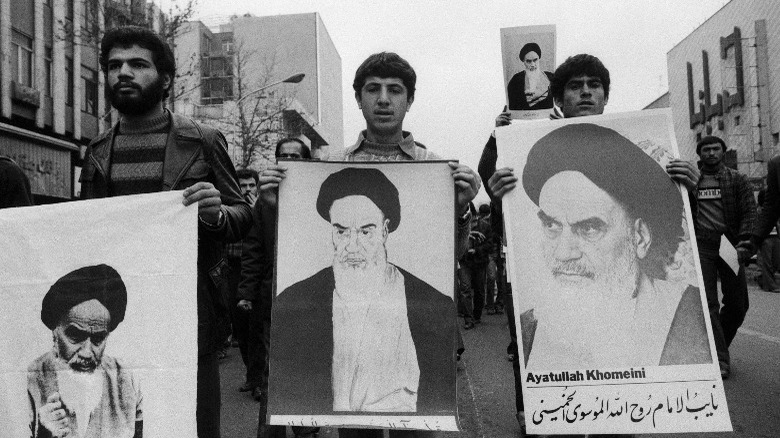

Probably the most influential event in modern Iranian history was the monumental 1978-1979 Iranian Revolution. As William L. Cleveland explains in "A History of the Modern Middle East," by the 1970s the shah was seriously losing his grip on power in Iran. Disaffection among the populace, many of whom were reading the religious and political teachings of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, with the royal government began to spill out into the public. After a clearly contrived article in an official Iranian newspaper slandered Khomeini in January 1978, there were protests in the streets of Iran, which ended with violent reprisals by the shah's military that left several dead.

The street protests continued throughout the year, and an economic recession — sparked by the shah's government -– only made matters worse. The shah's police gunned down hundreds of protestors in the streets, and as many as 2 million people demonstrated against him in December 1978. On January 16, 1979, the shah abdicated the throne and fled the country, never to return to Iran again.

Meanwhile, Khomeini arrived in Iran in February to massive public support, and he quickly became the head political leader. He removed all officials appointed by the shah and named his own prime minister, and he also formed the Revolutionary Guards — an internal armed force that helped him consolidate his power. By 1979 Iran had ratified a constitution, which enshrined the principle vilayet-e faqih and named Khomeini as the supreme leader.

Time once made him their Man of the Year

When you first hear about Time magazine's annual Man of the Year award, most people probably assume that the list is filled with some of history's most influential and positive people. And while that's certainly true, as the list includes incredibly important people like Martin Luther King Jr., Lech Walesa, and Mohandas Gandhi, it has also had some incredibly controversial choices -– like Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin (per Time). At the top of the list of questionable choices was Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1979.

1979 was the year of the Iranian Revolution, which is largely what garnered Khomeini the Time Man of the Year title. The magazine made some questionable claims in their article, including calling the revolution mostly non-violent, though it did note the questionable circumstances behind hundreds of summary executions during the revolution he oversaw. At the time of the article's publication on January 7, 1980, the Iranian Hostage Crisis had just started, and the article noted Khomeini's involvement and role in prolonging it.

As The New York Times pointed out at the time, multiple Time correspondents were actually kicked out of the country following the announcement that Khomeini was the Man of the Year, making their decision to follow through with it even more questionable.

He faced numerous early coup attempts

Coming to power in the midst of a revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's position was anything but secure for the first few years. In fact, he faced numerous unsuccessful coup d'état attempts from unhappy dissidents within his government. As per the International Journal of Middle East Studies, in July 1980, barely six months after Khomeini had consolidated his government, a coup attempt was sparked by anti-Khomeini forces within the Iranian military.

However, Khomeini's government knew about the coup beforehand and arrested and executed many of the plotters after it failed. Almost exactly two years later, in June 1982, Khomeini's government announced he had thwarted another coup attempt. According to Nikki Keddie in "Modern Iran," this attempt was put on by Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, and again failed horribly. The government executed Ghotbzadeh and put another ringleader on house arrest for four years until his death,

Though it never came to fruition, there was also an elaborate coup attempt that was almost put on by the shah's surviving son and the Israeli government under defense minister Ariel Sharon 1982. As Samuel Segev explains in "The Iranian Triangle," representatives of the shah's son contacted Sharon about arranging an arms deal to help remove Khomeini from power. Adnan Khashoggi, a Saudi arms dealer, helped arrange for $2 billion in funds, but the coup never got off the ground after the Israeli government refused to help.

Iran had numerous human rights violations under Ayatollah Khomeini

One of the reasons that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini is known as one of the most infamous world leaders in modern history was Iran's abysmal human rights record under his governments. According to the Iran Tribunal, an organization formed to investigate human rights abuses, Iran under Khomeini had committed massive violations in the 1980s when the government tortured or killed more than 20,000 Iranian citizens.

While they were not all his fault, the United Nations' Commission on Human Rights reported that the 1979 Iranian Revolution resulted in 7,000 deaths alone (per The New York Times). In just 1988, authorities murdered anywhere from 2,800-5,000 political prisoners, according to Human Rights Watch. It was Khomeini himself who gave the order for the executions via a fatwa (religious legal ruling).

As Amnesty International explains, Khomeini had initially come to power promising to curb the widespread torture and corruption of the shah's regime. However, Khomeini's government continued a legacy of torture that still continues in Iran through today.

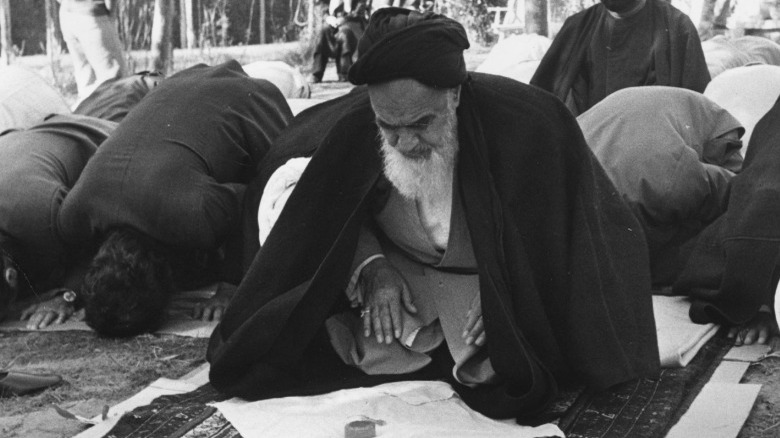

He redefined Shi a Islam

In late 1979, when the new Islamic Republic of Iran was formed under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the constitution explicitly enshrined the role of Islam in the government through the concept of vilayet-e faqih (guardianship of the Islamic jurist). As William L. Cleveland explains in "A History of the Modern Middle East," the concept of vilayet-e faqih ensured that Iran would always be ruled in accordance with Shīʿa Islam by a religious jurist (Islam does not have a clergy, as per the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops).

Khomeini laid vilayet-e faqih's foundation in the 1940s, and he greatly expanded it during his period of exile in Iraq, according to Saïd Amir Arjomand in "After Khomeini." While it might sound like vilayet-e faqih is just a simple call for a religious state, it is actually an incredibly revolutionary interpretation of Shīʿa Islam. Traditional interpretations of Shīʿa Islam held that Shīʿa scholars, like ayatollahs, were religious and not political authorities. However, vilayet-e faqih instead argues that religious scholars do have the political authority as leaders. This split with centuries of traditional Shīʿa teachings and was first created by Khomeini.

Additionally, if many jurists decide to follow one specific jurist and his teachings, that jurist is then elevated to the status of marja-e taqlid, also known as grand ayatollah –- a title Khomeini took (per "The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Politics"). The idea of vilayet-e faqih was also radical because it undermined the traditional independence of marjas' in Shīʿa Islam.

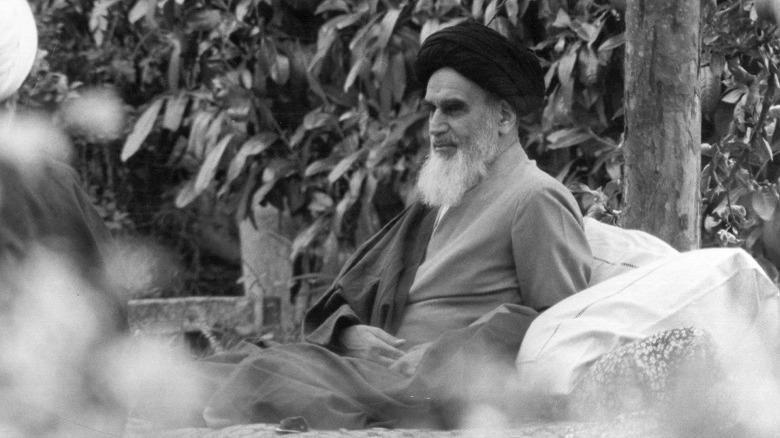

He named and then changed his successor

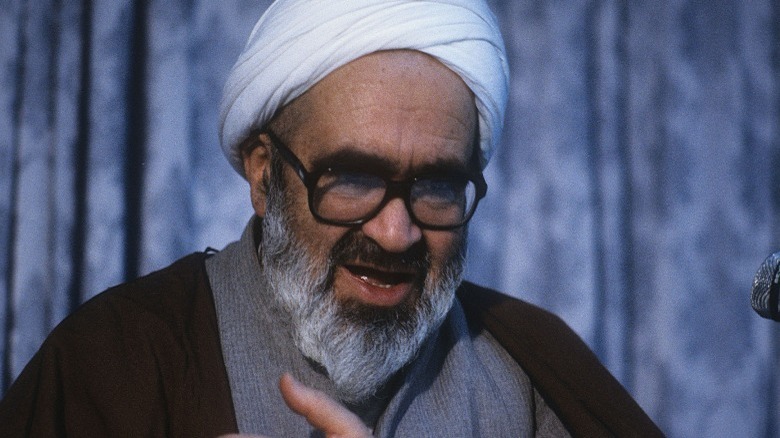

When Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was building up his reputation and credentials as a scholar in the Islamic world, he became a celebrated teacher to many young students of Shīʿa Islam. As PBS explains, one of the most influential students was the Grand Ayatollah Hussein Montazeri. Montazeri was a huge supporter of Khomeini while he was in exile and was arrested and tortured many times in Iran by the shah's police for his political protests.

Montazeri served as a deputy in the first Iranian government under Khomeini as chairman of the Assembly of Experts of the Constitution –- one of the highest ranking bodies in the Iranian government. In 1985, Montazeri became officially enshrined in Iranian law as the successor to Khomeini upon his eventual death. However, according to Nikki Keddie in "Modern Iran," Montazeri soon ran afoul of Khomeini.

One of his subordinates was found guilty and executed for colluding with the U.S. and Israel, and within a few years Montazeri was suggesting the government admit to problems and criticisms. Soon, his criticisms became public, and in 1988, after Khomeini gave a speech denouncing him, Montazeri was officially removed as Khomeini's successor. In his place the assembly eventually named Ali Khamenei, who would succeed Khomeini upon his death in 1989.

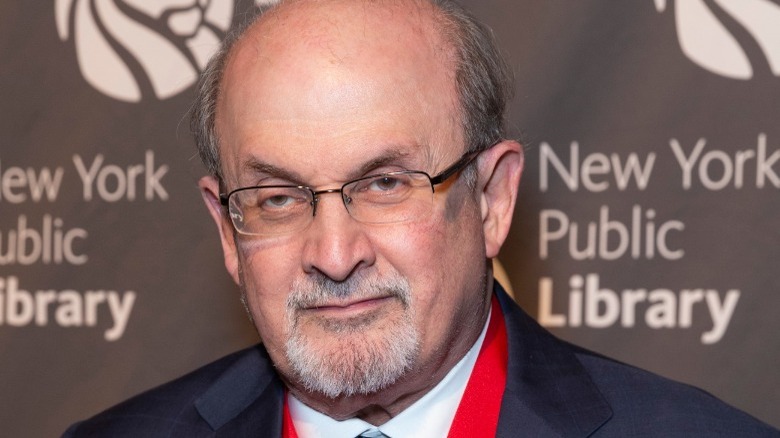

His controversial fatwa of Salman Rushdie

During his tenure as supreme leader of Iran, one of Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's most controversial public moments was his fatwa (religious legal ruling) concerning Salman Rushdie. As The New York Times reported at the time, Rushdie had recently released his famous book, "The Satanic Verses," which many readers found highly offensive to Islam.

Khomeini issued his fatwa in February 1989, which incited Muslims around the world to kill Rushdie and anyone associated with the book's publication or the publication company, Viking Penguin. Khomeini tried to encourage supporters to either murder Rushdie themselves or to capture him and have him murdered by someone else. Rushdie, who was born a Muslim, was upset by the ruling and denied that his book was anti-Islamic.

According to the Wilson Center, while Rushdie himself did not initially fall victim to the fatwa, several translators of his book were murdered in the early-'90s. In 1998, reformist Iranian President Mohammad Khatami claimed the fatwa was no longer in effect, but current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said the opposite in 2017, remarking it was still active. Rushdie started to appear publicly following Khatami's 1998 declaration, but in August 2022 he was stabbed by a Muslim dissident and supporter of Iran. This was just days following an online post from the Iranian government, which taunted Rushdie and republished the fatwa text.

His personal insult towards Jimmy Carter

The 1979-1980 Iranian Hostage Crisis was one of the most important events in American political history. The crisis was stirred by two interrelated events: the Iranian Revolution and the shah's entrance to the U.S. upon his diagnosis of cancer. Under enormous pressure, President Jimmy Carter had allowed the shah into the U.S. so he could receive cancer treatment, a move which infuriated Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and much of Iranian society. As Nikki Keddie argues in "Modern Iran," in November 1979, a mob of revolting Iranian students attacked and occupied the American embassy in Tehran over his admittance.

Khomeini gave the students his support, and he then used the crisis to consolidate his power and undermine the liberal Iranian government. The students ransacked the embassy and located many incriminating documents, which Khomeini-backers released in an effort to discredit political opponents.

The Iranian students held the hostages, which included more than 60 Americans, for 444 days until January 21, 1981 (via History). Carter had tried an ill-fated rescue mission of the hostages in Spring 1980, known as Operation Eagle Claw, but it ended in disaster as eight Americans died before the mission could start. The hostages' were only released after Ronald Reagan had been sworn into the presidency –- a final insult from Khomeini to Carter.

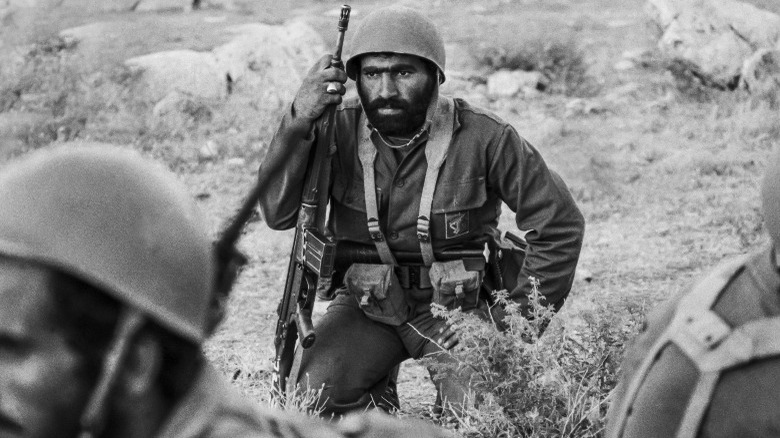

His entire tenure was clouded by war

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini established the Islamic Republic of Iran through the midst of a bloody and tumultuous revolution, and things did not get any more peaceful from there. As per William L. Cleveland in "A History of the Modern Middle East," the abdication of the shah and ascension of Khomeini to power immediately brought Iran into conflict with its neighbor to the west — Iraq — and war soon broke out in September 1980, when Saddam Hussein launched an attack and invaded the Iranian border.

What Hussein thought would be a quick war ended up turning into an almost decade-long affair of attrition, bloodshed, and death. Instead of the Iranian people rebelling against Khomeini and the new government, as Hussein had intended, they actually supported it in the war against Iraq. The U.S. supported Iraq financially and militarily during much of the war, but the Reagan Administration also sold weapons to Iran during the war, too (via Politico).

The war finally came to an end in the spring of 1988, when Hussein used poison gas against the Kurdish people in northern Iraq, killing 5,000 of them. Previously, Khomeini had pledged to never reach an agreement with Hussein, but he relented after nearly a decade at war. Khomeini died in June 1989, after eight of his 10 years in office were consumed by the war.