The Tragic 1898 American Massacre Many People Haven't Heard Of

The Wilmington Insurrection was one of the saddest events in American history. Unfortunately, it is also one of the least talked about and commemorated events in American history, too. The insurrection and subsequent massacre occurred in November 1898 in the small town of Wilmington, North Carolina. The massacre is just one of the tragic instances of horrific racism in America, and is comparable to the Tulsa Race Massacre and the Long Hot Summer of 1967.

It occurred during a period of horrifying racial strife and friction, one that lasted far too long in American history. As NPR explains, a white supremacist mob attacked several Black residents of the town, killing many of them and injuring countless others. By the end of the massacre, legally serving Black citizens had been thrown out of the city government and replaced by unelected segregationists.

For over a century since the insurrection, Wilmington has felt its echoes and reverberations throughout the city. This is the story of the tragic 1898 Wilmington Massacre you probably haven't heard of.

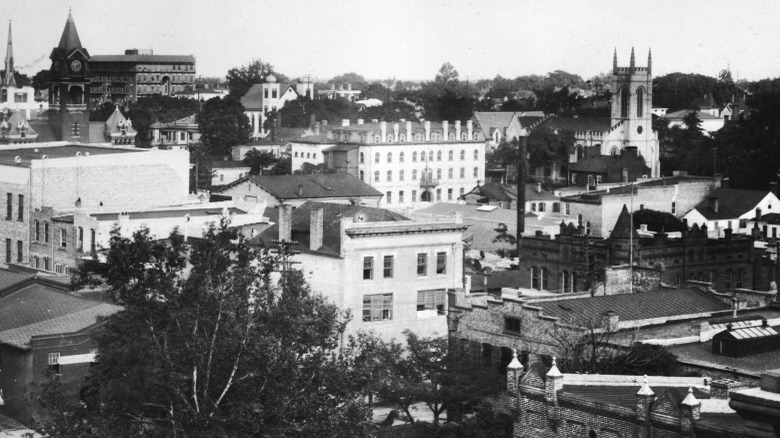

Wilmington Before 1898

Wilmington is one of the oldest towns in the United States, first being incorporated when North Carolina was still a colony back in 1739. As the Wilmington Race Riot Report explains, the town soon became an important and prominent part of the colony as its biggest port and a vital center of commerce. When the Civil War broke out in the 1860s, the Confederate Army used Wilmington as a part of the chain bringing supplies to troops in the field. The Union Army liberated the town in January 1865, to mixed reactions from the former-Confederate inhabitants.

The county Wilmington resides in, North Hannover, previously had one of the highest populations of enslaved people in the state, with almost double the average, leaving many disgruntled former enslavers when the war ended. However, it also had a considerable population of free Black citizens, some of whom owned significant real estate in the city. By the time of the insurrection in 1898, the Black population of Wilmington had over 126,000 registered male voters (via History). The city government was also composed of both Black and white elected officials.

Black citizens had benefited from the introduction of Fusion politics, which fused poor farmers and freed Blacks together into a potent voting bloc. Their opponents were the Democrats, the party that had opposed abolition during the Civil War. At the time, it seemed like the Black community was only going to continue prospering, but white supremacists in the city had other ideas.

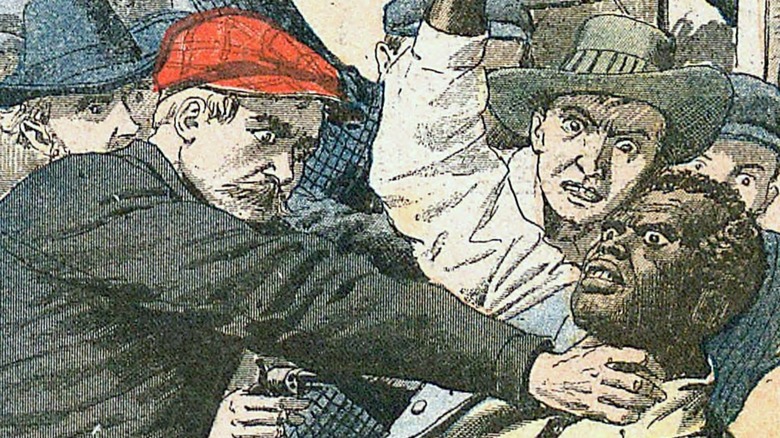

The war of words in the newspapers

Racial tension in Wilmington never completely healed after the Civil War ended in 1865 and slavery was abolished. As was the case in much of the South, there was still considerable hostility from many former Confederates and white slave owners toward the newly enfranchised Black citizens. According to the New Hannover County Government, in August 1897, white supremacist Rebecca Felton gave a racist speech where she directed her anger toward Black male citizens. Felton suggested they should be murdered because, she claimed, they would attack innocent white women unprovoked and were a danger to the community.

The speech made its way to Wilmington, where it was reprinted in one of the local newspapers. A year later, in August 1898, in response to the speech, one of the Black-owned newspapers in town, The Daily Record, posted an article that defended interracial relationships and noted they were based on love, not coercion. Though the article was anonymous, many historians consider the author to be Alexander Manly, The Daily Record's editor.

Another newspaper, the Wilmington Star, which was white-owned, printed a response to Manly's article. They titled the article "A Horrid Slander," and denounced Manly's article as an assault on white women. The arguing between the newspapers served to fuel racial tension that was already simmering in the area.

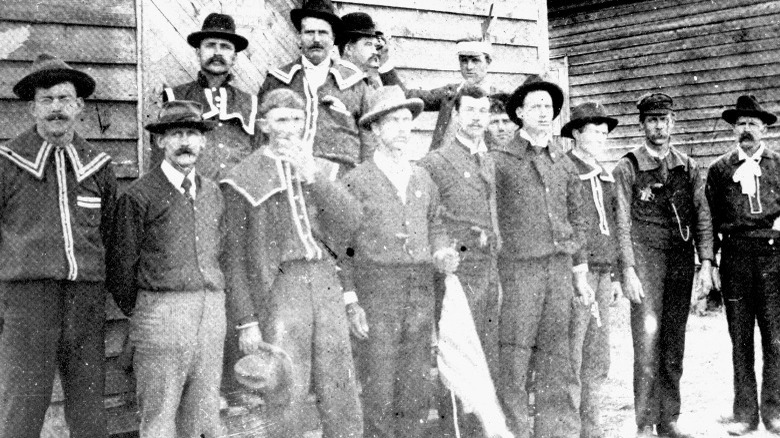

The campaign of terror and the 1898 elections

With the backdrop of the Spanish-American War breaking out in the Pacific and continued racial tension at home, the Democratic and Republican Parties in Wilmington prepared for the 1898 election season (via the Wilmington Race Riot Commission). The Democrats were a much more united party at the time, as fusion politics — which had originally brought the Republicans to the government in 1894 — was now starting to fragment. In the Spring of 1898, the Democrats held their convention, at which point they adopted a plank that called for white supremacist rule.

The Democrats also put out a handbook, which made false claims about Black citizens trying to take over and called Wilmington "white man's country." Their plan was to go after Republican voters and flip them to the Democrat party, and also to stop Black voters from going to the polls. Leading up to election day in November, as History explains, the Democrats instituted a "campaign of terror" against the Black voters in the city. They beat many of them and threatened death for those who were planning on voting.

One particularly infamous group was known as the Red Shirts, and they threatened both Black and white citizens into either not voting or voting Democrat if they did. The campaign was successful, and very few Black residents came out to the polls to vote in the elections. Not surprisingly, the Democrats blew out the Republicans in the election.

The White Declaration of independence

Immediately following their campaign of terror, on November 9, 1898, the day following the elections, a Democrat-led mob of over 1,000 residents met at the local courthouse. As The Weekly Star reported in the column "Citizens Aroused," the mob convened to discuss their plans for control of the city. They came up with a resolution, now known as "The White Declaration of Independence," which was published in its entirety in the Star the following day.

In a stunning mix of racism, ignorance, and hate, the citizens of Wilmington drafted a resolution that basically called for the violent evacuation of the town by Black residents and the abdication of their voting privileges as citizens. The resolution specifically mentioned the Civil War as the cause of the trouble, and pushed back on the mixed-race legislature that had previously presided over the city.

The declaration demanded that Black citizens be removed from jobs that were then to be given to whites, and argued that everything in the city should be done for the benefit of the white citizens at the expense of Black citizens. At specific issue was the article written by Alexander Manly in "The Daily Record" the August before the elections. The day following the meeting, a group of Black citizens was supposed to meet with the Democrats and let them know if Wilmington's Black community was going to obey the resolution or not.

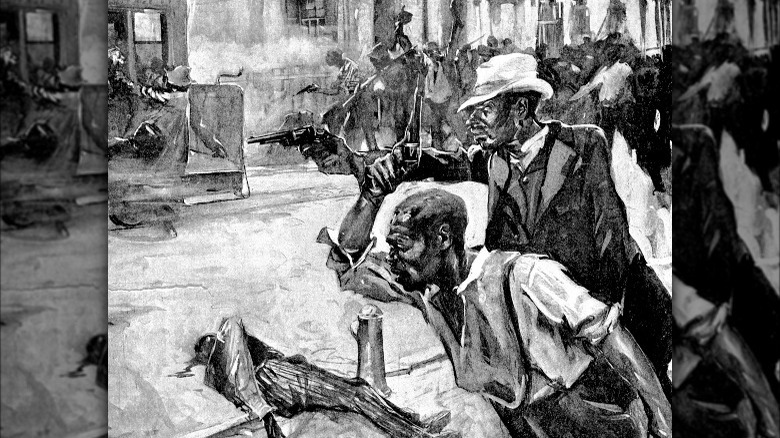

The Wilmington Massacre

Following the white supremacist mob's ultimatum to the group of Black citizens concerning "The White Declaration of Independence," the Black citizens immediately wrote a response. In it, they repudiated Alexander Manly's letter from "The Daily Record" and promised to try and carry out as much of the resolution as possible to maintain the peace (according to H. Leon Prather Sr. in "Democracy Betrayed"). However, the letter never reached the mob — though it likely would not have mattered anyway.

On November 9, 1898, white supremacists instituted a reign of terror against the Black citizens in Wilmington. A white mob formed under the leadership of Col. Alfred Waddell, the same person who had led the meeting the previous day and was one of the entire conspiracy's ringleaders. Eventually, 2,000 people composed the heavily armed and angry white mob. They immediately marched to the "Love and Charity Hall" and burned the building with the printing press that Manly had written his article on inside.

Soon, gunfights with Black citizens were erupting through the city, and smaller white mobs marched towards the Brooklyn section of the city and killed many Black citizens in volleys of gunfire. As Timothy B. Tyson explains in "The Ghosts of 1898," men were chased from their houses and executed in the streets by roving bands of white supremacists. Much of the mob wanted to completely cleanse the city of all Black citizens, and there were horrific stories of vigilantism against Black residents.

The horrific death toll

Even today, more than a century after the massacre, the total number of casualties is not known or agreed upon. As Timothy B. Tyson points out in "The Ghosts of 1898," estimates on the death toll range from single digits all the way to the hundreds. When they first reported on the massacre, The New York Times put the death toll at only nine bodies, and the ringleader Alfred Waddell put the number at more than double by counting 20. The New York Herald reported 15, and the Richmond Daily Times said 16 (via H. Leon Prather Sr. in "Democracy Betrayed").

Apparently, some bodies were buried privately before any official autopsy or record was officially taken. Some reports of the time have white supremacists killing over 100 people. The highest estimates put the death toll at over 300 residents, but the true number will unfortunately never be known.

In their 2006 report on the massacre, the Wilmington Race Riot Commission compiled a more accurate list of deaths associated with it. The commission lists 31 possible deaths, with the identities of many remaining unknown. An early history, written by Harry Hayden, listed far more deaths, but not all of them were able to be substantiated. Much of the destruction was caused by two massive guns the white supremacists had acquired just weeks before the election in anticipation of the massacre.

The flight of Black citizens from Wilmington

As white supremacists roamed the streets of Wilmington looking for violence, the entire community was put on edge. Both Black and white citizens immediately fled the downtown area, but they had very different options about where they could turn. As H. Leon Prather Sr. explains in "Democracy Betrayed," while white citizens could stay in the city at armed shelters to escape the violence, the Black citizens had nowhere inside the city where they were safe.

Hunted from all sides, many of them chose to flee to the woods to escape the hysterical and racist mob. Over 500 Black men, women, and children were reported to be in the woods, holding whatever belongings they could carry with them. To add to their misery, the majority of them were also freezing. Even though it was mid-November and temperatures were bitter cold, many of the families had fled in such a rush they did not have time to think about grabbing coats or warm clothes.

Standing in the woods and with many of them too scared to even move, the families were incredibly nervous that the massacre would spill out of the city and over to their encampment. Parents tried to comfort their frightened and crying children, and some of them turned to the Bible for strength and support. Thankfully, the mob did not chase them into the woods, and they were able to avoid them.

The post-massacre coup d'état and aftermath

While Black citizens huddled in the woods for days following the outbreak of violence and murder, the white supremacists set about executing their coup d'état and takeover of the city government. As H. Leon Prather Sr. explains in "Democracy Betrayed," on the day of the massacre, the ringleaders, headed by Col. Alfred Waddell, met and decided to implement their planned purge of Black officials and their sympathetic white counterparts who served with them. The mob demanded the resignation of the mayor, city aldermen, and the police department.

Under enormous pressure, all of them relented, and soon Waddell was elected the new mayor by a new all-white slate of unelected aldermen. The following day, as white Wilmington Democrats lined the streets, white soldiers forced six of the most important Black citizens to the train station at gunpoint. Once there, they told their captives they were never allowed to return and sent them north to Virginia. The mob then turned their sites on white Republicans in the city, almost lynching one of them before he escaped out of the city.

To consolidate their hold on power, the white supremacists purged remaining Black and fusionist leaders from city and government jobs, including any firefighters or police officers (per Timothy B. Tyson in "The Ghosts of 1898"). Black citizens were also prohibited from serving on any school boards. Incredibly, all the while, Waddell claimed that the new government had not been the result of intimidation.

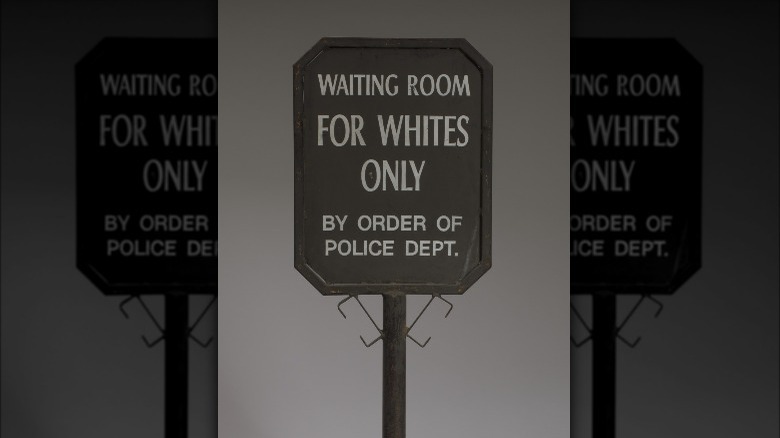

The implementation of Jim Crow

After consolidating control of the city government, firefighters, and police force, the white Wilmington Democrats set their sights on even more drastic measures. They quickly put a constitutional amendment on the ballot for 1900, which was one of the first Jim Crow-style laws in the South (via Timothy B. Tyson in "The Ghosts of 1898"). The amendment created a poll tax for voters as well as a literacy test — the latter of which was only enforced for Black citizens.

The New York Times article on the passing of the amendment underscored the depths of racist control of the city. The article called the amendment "a practical elimination of [Black citizens] from politics," and remarked on the incredibly small turnout of voters, and especially the lack of Black voters at the polls. However, none of the real history of the massacre was taught to the citizens of Wilmington for decades. In the aftermath, the newspapers almost unanimously sided with the Democrats and gave incredibly inaccurate pictures of what happened (via History).

The massacre was portrayed as a race riot rather than the one-sided slaughter it was. As Tyson points out, even textbooks used in Wilmington schools after 1900 either downplayed the severity or completely omitted it altogether. Many of them either tacitly blamed Black citizens for the riots or used racist tropes to defend it. It was not until close to the turn of the 21st century that any sort of balance was achieved.

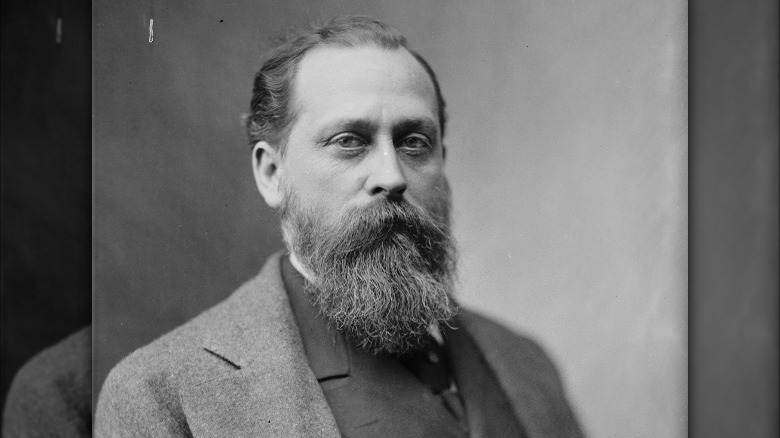

The white supremacists were rewarded

In the aftermath of the Wilmington massacre, rather than punishment, the white supremacists were widely rewarded and praised for their actions by their contemporaries. Unfortunately, many of the organizers of the massacre and insurrection were even elected to positions of prominence in the city, state, and federal governments.

The first was Col. Alfred Waddell (above), who was elected the new mayor of the city by the replaced board of aldermen. Charles B. Aycock, another ringleader, was eventually elected governor (via Timothy B. Tyson in "The Ghosts of 1898"). In the 1920s, Cameron Morrison, who had participated in violence with the Red Shirt mobs, ran for office and used his Red Shirt credentials to bolster his campaign. He was eventually elected to the U.S. Senate in 1901 and served again in 1930, and was also elected to the North Carolina governorship and the U.S. House of Representatives (via the North Carolina History Project)

Rebecca Felton, the woman whose letter in August 1897 had called for the slaughter of Black men, was made the first female senator in U.S. history when she served for one day in 1922 (per the U.S. Senate). John D. Bellamy, one of the organizers of the insurrection and white supremacy campaign, won elections in 1898 and 1900 to the House of Representatives (via the House of Representatives). He later became a prominent lawyer and was a highly respected citizen in North Carolina.

The insurrection left a legacy of racism in Wilmington

The impact of the Wilmington massacre and insurrection lasted far past the initial violence and bloodshed of November 1898. The implementation of Jim Crow legislation severely curtailed the political participation of Black citizens in Wilmington, ensuring that racist white supremacists would maintain control of the city for several decades. As History points out, by 1902, almost 100,000 registered Black voters had disappeared from the county's voting rolls, and it took more than seven decades for a Black person to hold public office in Wilmington.

As Tod Hamilton and William Darity explain in their essay on the economic impact of the insurrection and massacre, the Black population declined economically and socially after the riots. Part of this was the result of an atmosphere that was more favorable to and accepting of white business owners and laborers at the expense of Black business owners and workers. Black employment and business ownership fell relatively to whites as a result of the insurrection. It was not until the 1990s that Wilmington finally had a Black representative in Congress.

The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission and Monument

The legacy of the Wilmington massacre and insurrection will always live on, and in 2000, the North Carolina government started moving to take concrete steps to memorialize and commemorate the events. That year, the General Assembly implemented Senate Bill 787, which called for the creation of a commission to study the 1898 massacre and its legacy (via the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources). In 2006, the Wilmington Race Riot Commission issued a 500-page report on the events of 1898, using a variety of sources and evidence. The report found the massacre was purely the result of white supremacy and had severely impacted Wilmington's Black community for decades after.

The commission also held open hearings, and the report can be found here. In 2009, the head researcher on the commission, LeRae Umfleet, published a book, and in 2020 a revised edition was released. One of the sponsors of the Senate bill that created the commission was Luther H. Jordan, a Black senator from North Carolina.

In 2008, the city of Wilmington constructed the 1898 Monument to acknowledge the massacre and its legacy (via U.N.C.-Chapel Hill). The monument is composed of several massive bronze statues and walls, and has an inscription memorializing the events.