The Tragic 2004 Death Of Spalding Gray

The actor and playwright Spalding Gray, famous for his monologues about life on the East Coast, was found dead in New York's East River in March 2004. He'd been missing since that January. As Today reported, it was assuredly a suicide. Per The New York Times, it was believed he jumped off of the Staten Island Ferry. Gray had struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts for years and had already made a number of half-hearted attempts. He was 62 years old.

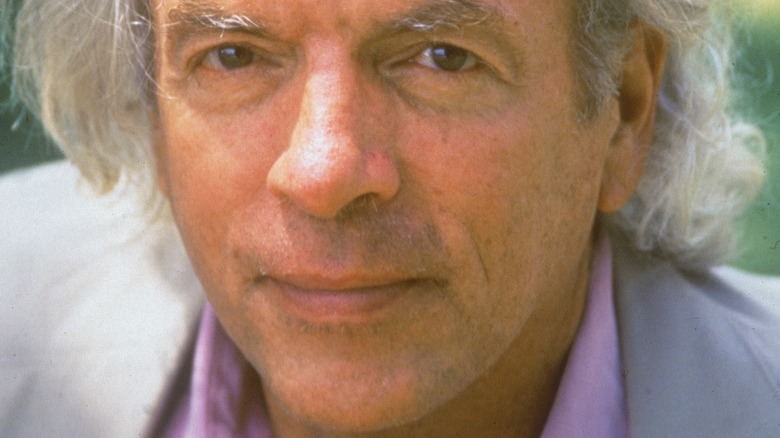

Gray had made his name writing one-man plays, like "Swimming to Cambodia" and "Booze, Cars and College Girls." Immediately recognizable by his spare build, mane of gray hair, and uniquely East Coast voice — he seemed incapable of pronouncing the letter R after a vowel — Gray had starred in films, published some of his monologues as books, accumulated an Obie, a Tony, and a cult following. Yet few of his fans understood the depths of Gray's suffering. His mother had died by suicide in 1967 when Gray was around 26, which left him obsessed with self-harm and the nature of death for the rest of his life. Then, in 2001, Gray sustained a head injury from a traffic accident in Ireland. It seems the damage from the accident may have worsened his depression, leading to a string of suicide attempts.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The frontal lobe

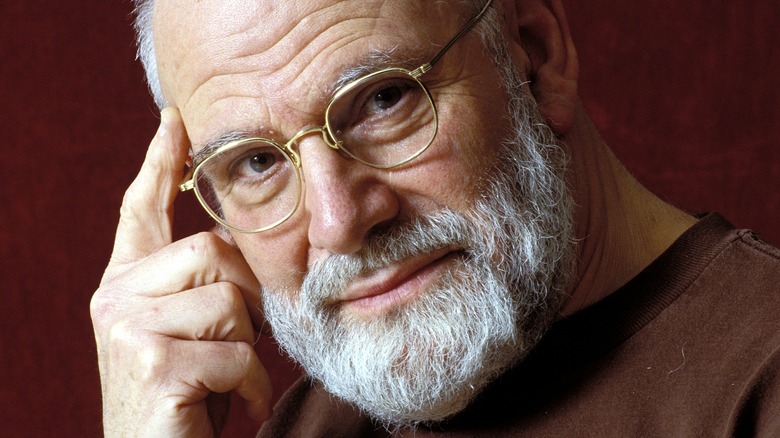

In 2015, The New Yorker ran a story by the famed neuroscientist and psychiatrist, Oliver Sacks (shown above), about Gray's last days. Gray, with the help of his wife, had contacted Sacks in 2003. After their road accident in Ireland two years earlier, in which Gray had hit his head, Gray didn't seem quite the same man. He had sunk into a kind of inescapable depression, and Sacks observed that he was almost catatonic, moving and speaking as little as possible. This was especially bizarre in a man whose life's work revolved around demonstrating emotion through his words, voice, and facial expressions.

Sacks wondered whether the injury to Gray's frontal lobes, the part of the brain that (among other things) regulates emotion, had unleashed an "uncontrollable rush of previously suppressed or repressed thoughts," including his longtime obsession with suicide. He noted that impulsivity, the tendency to act without thinking, is characteristic of an undeveloped front lobe. One of the reasons children are more impulsive than adults, for example, is that their frontal lobes are underdeveloped. Was this the reason that Gray finally ended his life, without warning or even a note?

Born of the flesh?

Is that possible? Can an injury to the head change someone's personality so dramatically?

The answer is yes, and sometimes in bizarre ways. One Hungarian soldier in World War I sustained a gunshot to the head and didn't sleep again for 40 years. But the most famous case of a personality warping under the force of traumatic brain injury was that of Phineas Gage. Gage was a railway worker. In 1848, he was tamping gunpowder to clear land for new tracks when the powder ignited and blew up, sending a thin metal rod through his eye and into his frontal lobe, finally boring through his skull. Gage survived, but something had changed; one of his friends said that he "was no longer Gage."

The changes to Gage's personality may or may not have been exaggerated, but it raises an inevitable question. Is our personality a matter of "hardware" or "software?" Cases of brain trauma like Gage's or Gray's may suggest the former, but the question is far from settled. Besides, these armchair discussions seem frivolous and cheap when applied to someone's life. Spalding Gray's death was not a college debate topic: it was a tragedy.