The Bronze Age Timeline Explained

Sure, the Bronze Age may be literal ancient history, but don't think that's cause to dismiss an entire era. The millennia that covered this period of time — about 3,800 B.C. to 400 B.C., per the World History Encyclopedia — saw some serious innovations. It wasn't just the development of bronze-enhanced weaponry and tools, either, though that leap forward certainly increased both the economic prosperity of civilizations and their capacity for bloodshed. The Bronze Age also saw the introduction of the wheel, widespread domestication of horses, and the rise of a little something called writing.

If alphabets and wheel axles aren't impressing you, then perhaps you could also look to the grand structures built by the people of Babylon, Minoan Crete, and Mycenae, among many others. The arts of the Bronze Age were likewise dazzling, including the complex metal vessels used by the rulers of ancient China to appease the ancestors and keep their power stable.

With so much to cover, the scope of the Bronze Age can start to feel pretty daunting. Never fear, though. With an overview of one of the most consequential eras in ancient history, here's the timeline of the Bronze Age explained.

Bronze hit the scene more than 5,000 years ago

Though there were plenty of big things that went on throughout the Bronze Age, the beginning of it all comes down to one major development: bronze. While the metal may seem ho-hum today, its appearance on the world stage was a big deal. According to History, this alloy of copper and tin proved to be far more durable than old copper or even stone tools. Pinning down the exact date when humans started creating bronze is tricky, though archaeological investigations point to sometime around 3,000 B.C. or 2,500 B.C. (via Copper Development Association).

According to the Copper Development Association, it's the seemingly humble tin that's one of the key players in this age. Tin ore is harder to find than that of copper, which meant that the few places with access to tin held real economic power.

In Britain, tin deposits in Cornwall were turning heads and garnering trade as early as 1,000 B.C. Ingots cast on the island may have found their way far to the south in the Mediterranean, where bronze continued to be used for tools and weapons for more than two millennia.

The wheel was probably invented in the Bronze Age

Cartoons and vague recollections of sleepy history classes may have you thinking that the wheel was a Stone Age invention that came rolling out of a cave somewhere. In fact, as ThoughtCo reports, the wheel was actually pretty late to the party of human inventions. People were already farming, weaving, and piloting boats across the seas before anyone thought of the wheel. The earliest known evidence for the wheel comes from the early Bronze Age, around 3,500 B.C.

This wasn't a wheel on a wagon or cart, either. The very first wheel anyone's found so far was actually part of a Mesopotamian potter's wheel, used in a horizontal fashion to create ceramic goods. That pottery connection may go even further, WIRED notes, as the next major development in the wheel, the axles, was made out of clay. Those axles were meant to keep a small animal figure rolling — yes, the first known use of the wheel to roll something along appears to be for a child's toy.

The wheel wasn't invented in just one place or by one person, either. There's clear evidence that plenty of people came up with the idea during the Bronze Age, including another wheeled toy buried with a child near modern-day Mexico City (via WIRED). Full-sized versions of this setup — that is, a cart pulled by domesticated animals like horses or oxen — wouldn't hit the scene for a few more centuries.

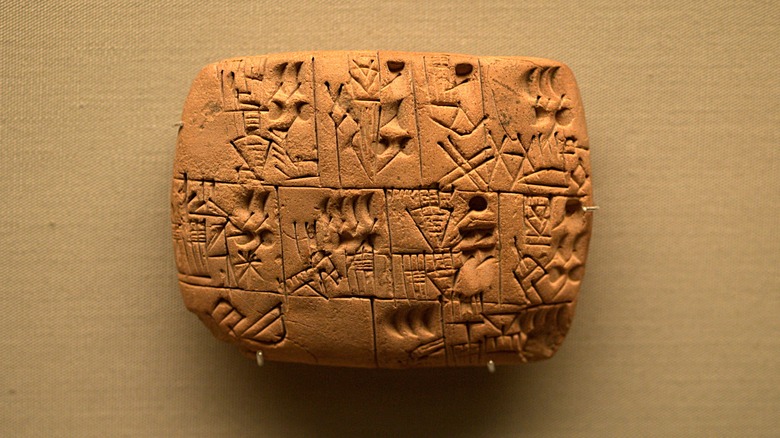

The Bronze Age saw the beginning of writing

With trade routes humming along and wheeled contraptions starting to take off throughout the Bronze Age world, it must have become clear that humans needed to get more organized. While communicating by speech and using one's memory to recall various deals, relationships, and good stories may have worked for local and small-scale stuff, it could only go so far. This need was so universal that writing was invented on at least four different occasions, per the British Library. The Sumerians seem to have gotten there first, premiering the wedge-shaped cuneiform script used in Mesopotamia from around 3400 B.C. According to the Getty, cuneiform managed to keep written Sumerian alive long after the spoken version went extinct, sometime around 2000 B.C.

According to the British Library, ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs followed soon after in about 3200 B.C., with some of the earliest known examples of Egyptian writing being labels intended to organize goods in the tomb of the mysterious Scorpion King. The Egyptians also appear to have innovated the use of ink and brushes, the latter made from reeds. It is thought that carved writing was meant for the ego-boosting projects of rulers, like temples and tombs, while inked writing was meant for more everyday administrative tasks.

Chinese script got started by 1300 B.C. in the late Bronze Age, while the indigenous people of Mesoamerica started writing things down by about 900 B.C. (via the British Library).

Sumerians irrigated the desert

By the beginning of the Bronze Age, many people were already old hands at agriculture. The Agricultural Revolution, also called the Neolithic Revolution, saw humans start farming in the Middle East about 12,000 years ago (via History). Agriculture was the likely genesis for many other human innovations that followed, like the rise of cities and art, as well as less-laudable developments such as warfare. It caused populations to boom and trade networks to blossom, while it may have also paved the way for new diseases and more severe epidemics, per Science.

Whether you deem the rise of agriculture to be a boon or curse, it was nevertheless central to life by the time of the Bronze Age. Caring for crops was all the more important in places like Mesopotamia, where rain could be scarce, spurring the people of this region to invent irrigation. Ancient Mesopotamia also happens to have the most complete record of irrigation systems, starting in the 3rd millennium B.C., per NYU's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. They also wanted to control the regular flooding of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, which could have been just as disastrous for crops and hungry Mesopotamians as a drought.

Sure, irrigation ditches may not make for exciting party banter, but the watering system of Bronze Age Mesopotamia led to many other big things, like crop surpluses, increased trade, more complex societies, and the rise of politics.

Ancient Greece got its start around 3200 B.C.

Though you may have learned about ancient Greece already, the tales of classical Athens or the quasi-romantic exploits of the god Zeus only cover a portion of Bronze Age Greece. For example, the Athenian acropolis — one of the most famous symbols of this ancient society — was only built in the fifth century B.C., per History. Given that people were setting up civilizations in the area for thousands of years before that, there's a lot of history you may have missed.

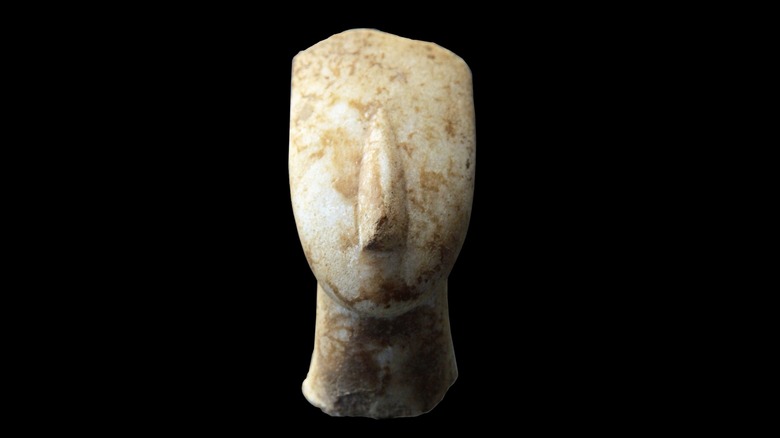

One of the first to make waves in Bronze Age Greece were the Cycladic people. According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, they first appear in the archaeological record about 3200 B.C. They were especially well-situated along trade routes in the Aegean Sea, not to mention the fact that many settlements were practically on top of rich copper deposits.

They were alone in the Mediterranean, however. The Minoans, based on the large island of Crete, became a dominant cultural and economic force starting around 2000 B.C. (via World History Encyclopedia). They built elaborate palaces full of frescoes — buildings so complicated that they may have led to the legend of the minotaur held in a labyrinth, near the Cretan palace of King Minos.

Troy was established around 3000 B.C.

The city of Troy may seem like a complete fabrication, and understandably so: Many know about it from Homer's "Iliad," the epic poem that purportedly tells the tale of the end of an agonizing Bronze Age war that laid waste to the city (via World History Encyclopedia). With its talk of gods and goddesses, you may think that Troy is just as unbelievable. But, according to the BBC, 19th-century excavations in Turkey uncovered a city in just the right place. What's more, there's evidence of warfare in the hints of a large fire and a scattering of arrowheads from the Bronze Age. Nonetheless, historians doubt that the "Iliad" is really accurate, not least because it claims that the war lasted a decade. Still, Troy appears to be a real place.

It didn't start out as a grand city, however. According to the World History Encyclopedia, it began as a village hemmed in by a stone wall around 3000 B.C. Over the centuries, it grew larger and more complicated, with strong evidence that the city's inhabitants traded for precious commodities from faraway lands, like gold jewelry and lapis lazuli stones.

The settlement was eventually surrounded by strong walls, hinting at a serious conflict around 1250 B.C. Eventually, ancient Troy fell into decline, though people kept living there into Roman times, in the fourth century A.D.

Horses teamed up with humans

Teasing out the history of horses is a bit of a tricky proposition. Sure, there's plenty of evidence regarding the evolutionary history of equines, as Smithsonian Magazine reports. The hard part is figuring out exactly when horses went from being wild, free animals roaming across Eurasia to the domesticated creatures we know and love today.

There's some tantalizing evidence that horses may have been domesticated in the Stone Age, but the increasing number of artwork featuring these animals might also have been a symptom of human fascination with the still-wild animal. There's also decent evidence that people were eating potentially domesticated horses around 3,500 B.C. in what is now Kazakhstan, as well as consuming mare's milk, and maybe even bridling them.

The catch? Those horses aren't the genetic ancestors of the ones prancing around the barnyard today. We can at least be pretty certain that domesticated horses really got their start in the Bronze Age, around 2,000 B.C. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it's generally accepted that the Sintashta people were traveling between Europe and Asia while riding on horses and in horse-drawn carts. Eventually, domesticated horses became a staple in much of the Bronze Age world, making it down to Mesopotamia around 2400 B.C. (via Penn Museum).

Northern Europe got to the Bronze Age later

While the civilizations of Mesopotamia and the ancient Mediterranean were among the first to join the Bronze Age, they certainly weren't the last. The innovations needed to work bronze began to spread across the known world, making its way north into Britain and Ireland around 2000 B.C., according to "The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age."

In Britain, the early Bronze Age saw the rise of the Wessex culture, whose people likely came to the island from northern France. Given their continental connections, the Wessex people appear to have opened up trade with the rest of Europe and paved the way for the unique material culture of the region (via Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society).

Bronze began to reach other parts of northern Europe in later centuries. The ancient Norse, for instance, didn't really join the Bronze Age until 1500 B.C., according to "Pathways to Power." Once it got going in the region, the landscape changed dramatically, as when many Nordic people began constructing large earthworks known as barrows. The people buried in these barrows were often laid to rest with a rich array of goods that spoke to greater knowledge of metalworking, not to mention serious trade links with outside societies. These include elaborately-decorated swords, wooden carvings, luxe textiles, and ritualistic jewelry.

The Bronze Age reached China by 1600 B.C.

Bronze turned out to be a far-traveling innovation, popping up not just in Europe but also much farther afield in what's now China. According to History, the dominant ruling classes in Bronze Age China were the Shang Dynasty, which reigned beginning around 1600 B.C., and the Zhou Dynasty, which took over in 1046 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes that working metal into bronze appears to have developed independently in China. This is supported by the evidence of a unique casting method known as piece-mold casting, which involves a clay mold that's disassembled and then fired into one piece before it's ready to accept molten bronze. Though it's more laborious than the lost-wax method employed elsewhere, piece-mold bronze can produce a seriously high level of detail.

According to Columbia University, society here was highly stratified, with pampered nobles going out to wage war in their bronze-enhanced chariots and bronze weapons. They managed a series of minor nobles who, in turn, lorded it over peasants working the countryside. It wasn't all fine foods and glorious battles for the king, however, as he was expected to keep up a series of complicated rituals to appease the ancestors and other deities. If he faced a poor reading from the oracle bones or made a misstep that displeased the spirits, all of the people could be impacted. Some of the sacrifices of food and drink presented to these spiritual forces were housed in finely decorated bronze vessels, which eventually became symbols of royalty.

Law codes appeared around 1772 B.C.

As the Bronze Age progressed, societies grew increasingly complicated. Many soon found themselves dealing with complex trade networks, dense cities, the specter of war, the rise of a ruling political class, and the whole idea of class stratification in general. For some, all of this meant that the informal laws of earlier eras just weren't going to cut it. Instead, they needed to put things down in stone — literally.

Perhaps the most famous example of a Bronze Age set of laws is the ancient Code of Hammurabi. Named after a Mesopotamian king who ruled Babylon from about 1894 to 1595 B.C., the Code is one of the earliest of its kind, according to History. Containing 282 rules that cover everything from business dealings to capital punishment, it was carved onto a gigantic black stone pillar weighing four tons. The wedge-shaped cuneiform text also takes some time to butter up Hammurabi himself, who's also seen in a carving at the top of the pillar, receiving the law code from Shamash, the god of justice.

The Code of Hammurabi also reveals the social stratification of Babylonian society, as it lays out different consequences for three different classes: those who hold property, those who are freed enslaved people, and those who are currently enslaved. For instance, a doctor who kills a patient through negligence could have his hands cut off if the victim was of the landed class. A dead enslaved person, however, would only merit a fine.

Mycenae made waves in Greece

Mycenae may be mentioned in mythology, but it was also a very real city in Bronze Age Greece. According to the World History Encyclopedia, the almost certainly fictional tale of its founding comes courtesy of Medusa-slaying Perseus, who named the site after a bit of his sword's scabbard fell off ... or after he found a spring and a mushroom together. In the world of confirmed facts, the origin of this hilltop city is much murkier.

Mycenae was a settlement in the Stone Age, but it doesn't appear to have really ramped up activity until around 2,100 B.C. That's where archaeologists have dated finds like city walls and noticeably nice grave goods. Over time, things got even nicer, with the addition of a palace and more luxurious tombs, as well as more practical engineering projects such as dams and defensive walls. Some of the high-class dead were buried with golden masks, one of which was erroneously said to be that of the legendary king, Agamemnon.

Nothing lasts forever, though. Archaeological evidence shows that the palace was likely hit by an earthquake later in the Bronze Age, and its successor shows signs of fire. After the Bronze Age, other Greeks seemed to have moved in, but it was only to be a short respite from what proved to be an inexorable decline.

Many civilizations faced collapse

For a while, things were looking pretty rosy for the Bronze Age. Civilizations on multiple continents were humming along, prospering on trade and creating lasting legacies of art and culture. But all of that interaction could be bad for business, too, as the Bronze Age saw plenty of war, given how almost everyone saw fit to not just build stronger weapons but also to boost their fighting forces (via "Warfare in Bronze Age Society").

Things began to crumble around 1,200 B.C. That's when most scholars pinpoint the first rumbles of the Bronze Age Collapse, when many civilizations fell into ruin. According to the World History Encyclopedia, this wasn't just a slow decline, either. Cities experienced catastrophic ruin, entire writing systems disappeared, and death seemed to sweep across entire regions. Yet no one's entirely sure what exactly caused this oftentimes catastrophic series of events. It may have been a cascade of different woes, including climate troubles, plagues, earthquakes, and political instability. There's also the rise of the Sea Peoples, a group of ancient pirates who certainly didn't help things by targeting settlements throughout the Mediterranean, most notably in Egypt.

Nonetheless, other groups motored along for quite a while, like the Scottish Bronze Age people who kept going until the eighth century B.C. before transitioning into the Iron Age (via Scottish Archaeological Research Framework).