The Italian Prime Minister Who Was Tried For Murder

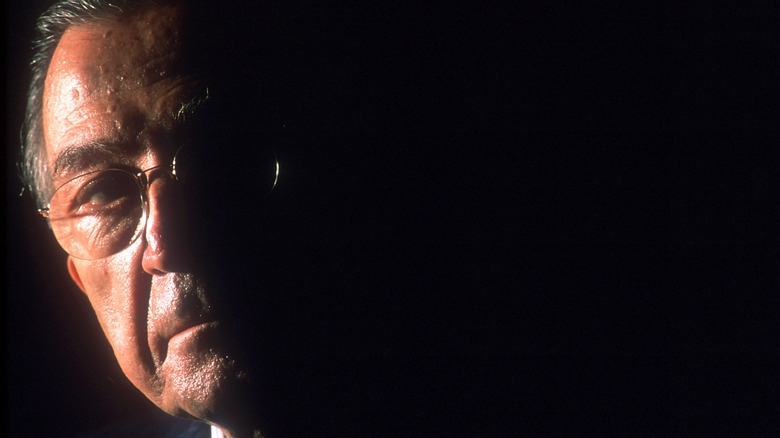

Hunched, horn-rimmed, tight-mouthed, with ears like bat wings, Giulio Andreotti's face was a permanent fixture of Italian news from the birth of the Republic in 1946 until the 2000s. He served as Italy's prime minister four times; held almost every ministerial post available, from foreign affairs to finance; and guided, or manipulated, the center-right Christian Democratic Party for decades (via Britannica). Italian politicians tend to be characters, glamorous or bilious or silly. Andreotti was quiet and guarded. Yet power was his food and drink. Paolo Sorrentino's 2009 biopic of Andreotti was appropriately titled "Il Divo," after Julius Caesar's sobriquet (the trailer is on YouTube). Andreotti was linked to everyone. He was a member of the outlawed Masonic lodge "P2" in Rome, widely thought to be involved in the aborted, neofascist Borghese Coup of 1970 and the kidnapping of prime minister Aldo Moro (via Reuters); many accused him of close Mafia ties.

But the most scandalous affair in Andreotti's endless career came in 2002, when the 83-year-old was convicted of orchestrating the murder of journalist Mino Pecorelli, who had been investigating Andreotti's circle. As CNN reported at the time, the conviction was overturned the next year.

The Christian Democrats

If you want to understand Andreotti's rise to power, you have to understand the nature of his political party. After all, he dedicated his life to the now-defunct Christian Democratic Party (known as the Democristiani, or DC), in one way or another.

Christian Democracy is an ideology that still dominates a number of European countries, like Germany. As Britannica explains, it is closely tied to the Catholic Church and the Catholic understanding of social justice (although Protestant variants exist). Opposed to fascism and communism, Christian Democrats stand for republican government, social conservatism, and a united Europe. The movement is generally favorable to big business and skews right, although some Christian Democrats identify with the center-left. Andreotti would oscillate between the right and left wings of the party, as the wind blew.

Italy's DC was one of the biggest such parties in Europe. Its founder, Alcide de Gasperi, is considered a founding father of the European Union (via European Commission). (He's pictured above, right, with a young Andreotti.) However, DC was also tied up in less savory activities than trade blocs and Catholic youth groups. In Sicily, DC was the de facto party of the Mafia. The Mafia could stamp out DC's left-wing enemies, as The New York Times reported; in exchange, DC would cut Mafia bosses in on fat business deals.

The Years of Lead

It's also important to realize what a violent, unstable country Italy was during the height of Andreotti's career. From 1969 to 1982, Italy was racked by terrorist attacks by far-left and far-right militants. The press dubbed the period "gli anni di piombo," or the Years of Lead. The Middlebury Institute keeps a list of the most egregious attacks, from the bombing of Milan's Piazza Fontana in 1969 (17 dead, 84 wounded) to a massacre of civilians at the Bologna train station in 1980 (85 dead, over 200 wounded).

The most famous terrorist attack of all, however, was the kidnapping of Aldo Moro by the far-left Red Brigades in 1978. Moro, like Andreotti, was a former Christian Democratic prime minister; he was notably farther to the left than Moro, and had formed a coalition government with DC's traditional enemies, the Communists. History recounts how the Red Brigades, furious that the Communists had "sold out," kidnapped Moro and put him on "trial" in a basement (and sent the above photo to the press). His body would be found in a parked car in Rome. So goes the official story; details remain murky.

Criminal violence spiked as well. In Palermo, rival Mafia clans fought so viciously in the 1980s that The Guardian referred to that period as "the lowest point in Sicily's history." And the 1982 suicide of Vatican financier Roberto Calvi, known as "God's banker," was widely suspected to not be a suicide at all (per Forbes).

The slain reporter

Rumors have always circulated above Andreotti's secret involvement in the deaths of Moro and Calvi. He was even implicated in the murder of two beloved Sicilian anti-Mafia magistrates, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, as The New York Times reported. But he would only go to trial for one murder, that of a relatively obscure journalist, Carmine "Mino" Pecorelli.

Pecorelli was editor-in-chief of a Rome magazine called Political Observer, that specialized, in the Times' words, in "political gossip." One night in March 1979, Pecorelli had just left the Observer's office and gotten into his Citroën when two unidentified men shot him through the window, once in the mouth and three times in the back, per Wired. A Mafia hitman and a right-wing terrorist would both be arrested for the murder.

In Wired's words, a lot of people wanted Pecorelli dead, and it wasn't immediately clear who had finally done it. But a Mafia turncoat, Tommaso Bruscetta, testified that the men who killed Pecorelli had been hired, through a murky chain of command, by Andreotti. Apparently, Pecorelli knew certain details about the Moro kidnapping that Andreotti wanted sealed. (Did Washington D.C. want to halt the left-wing drift of the party, as The Guardian suggests?) The investigation took decades, but by 1996 Andreotti was in court, declaring his innocence.

Guilty or not?

This was not Andreotti's first such trial, but it was the first time he could not find an adequate alibi. In 2002, after eight years of testimony, acquittals and retrials, the Court of Appeals at Perugia found him guilty of complicity in Pecorelli's death, and sentenced him to 24 years in prison (via CNN). The judges had deliberated for three days, behind closed doors.

The elderly Andreotti was at home during the trial. CNN quotes his statement to the press: "I have always believed in justice and I continue to believe, even if this evening I find it difficult to accept such an absurdity."

Perhaps the good churchgoer was rewarded for his faith, or maybe justice and the law operate in different spheres. In any case, Andreotti's appeal at the Court of Cassation, Italy's Supreme Court, worked. In 2003, the conviction was overturned, writes CNN. The court had found the testimony of the Mafia turncoats incredible. Andreotti would die a free man in 2013, aged 94. His party had fallen apart in the corruption scandals of the 1990s; his old enemies, the Communists, had collapsed with the Berlin Wall; most of his colleagues were long dead. His secrets, so terrible and so tantalizing, belong to a world that no longer exists.