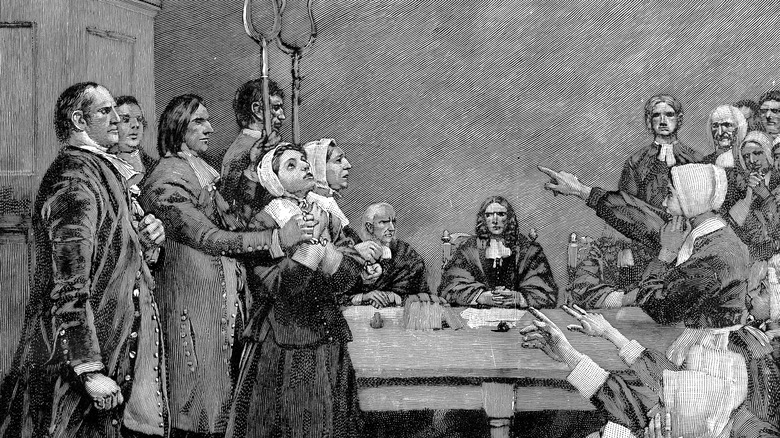

Things You Get Wrong About The Salem Witch Trials

They happened over 300 years ago, yet the Salem witch trials still haunt the imagination of the American public, and the world – partly because the outbreak of witchcraft accusations in this tiny New England community was so swift and inexplicable. Multiple theories abound as to what led people in Salem to turn on their neighbors. Some put it down to religious fundamentalism, misogyny, drug-induced hallucination, or the frenzied antics of a community under siege from threats both real and imagined. These theories contrast sharply with the calm, measured way major intellectual figures of the day processed legal documents describing the threshold of proof required for a witchcraft conviction. This meant that convictions and executions were not as defined by cavalier cruelty and hysteria as is often portrayed, which perhaps makes the events at Salem all the more horrifying to contemplate, and understand.

One can only say confidently that the story of Salem is far more complicated than the simplistic version that has filtered into the popular imagination. For one thing, the Salem witch trials didn't occur at the height of a slew of witch hunts across the world. Neither did they kick off a global movement. By 1672, witch trials were dying out, and in 1730 a law was introduced in Britain that said witchcraft could only result from those accused of being charlatans or con artists – not from having practiced actual magic, as described by the BBC.

Multiple other misconceptions abound about the Salem witch trials. Read on to learn more.

Convicted witches were burned at the stake

The image of witches being burned at the stake is a widespread one, but it is a myth when it comes to Salem. Roasting people alive was not the preferred method of execution for accused witches in English-speaking countries. English Heritage highlights that most convicted witches in America and England were hanged. It was only in Scotland that burnings occurred, but even there, it was only to dead bodies; the convicted had usually been strangled first.

In Salem, according to Smithsonian Magazine, the town's makeshift gallows (a tree) saw three mass executions, including the killings of Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Rebecca Nurse, and Sarah Wildes, all in one day in 1692. Britannica describes how George Burroughs, a minister accused of being a witches' ringleader, recited the Lord's Prayer before his execution, something thought impossible for a wizard or witch to do. Doubts were cast on his guilt by the onlookers but were quashed by Cotton Mather, a noted intellectual and sometimes supporter of the trials.

The accused were hanged from an oak tree before their bodies were dropped into a shallow "crevice" below, where their grief-stricken families could secretly collect their bodies. As they were considered to be handmaidens of Satan, none of the accused were allowed to be buried in consecrated ground. However, it's believed, according to Biography, that at least three of the convicted – Rebecca Nurse, John Proctor, and George Jacobs – were collected by their families and given Christian burials.

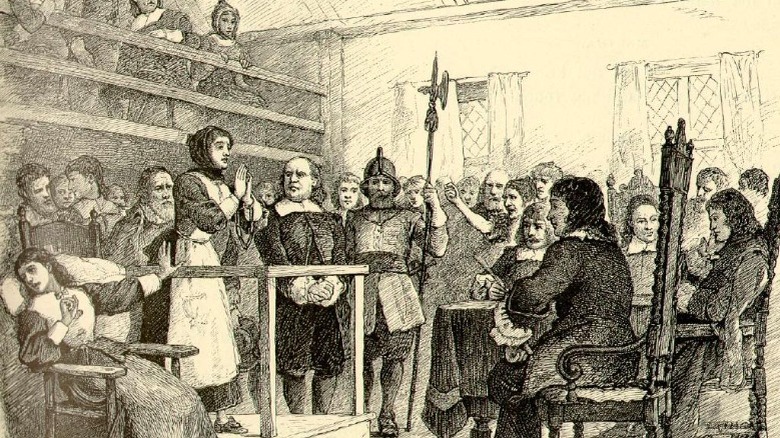

The accused were women and the accusers were men

It's true that the majority of the 20 executed in Salem were women, and that many of those in senior positions who presided over the trials and executions were men. Women in Salem didn't make accusations against their husbands (whereas plenty of men implicated their wives) and fathers and sons rarely accused each other (via The Washington Post). Yet many of the accused were older and more vulnerable women in the community who were being attacked by young girls, including Elizabeth Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams – whose testimonies of fits, twitching, and comatose states kicked off the persecution – who were only aged 9 and 11 respectively, according to Biography.

Furthermore, six of those executed were men. As the Salem Witch Museum points out, they included John Proctor, a wealthy local landowner and tavern-keeper who was disliked by people in the community, not least because he was outspoken against the trials and then refused to plead guilty. He forgave his accusers before he died, and was later immortalized in Arthur Miller's play "The Crucible."

One of the men was the only victim not to be killed by hanging. The Massachusetts Historical Society describes how Giles Corey was accused of bewitching people with specters. He refused to make any kind of plea in order to protect his sons' inheritance and was punished by being crushed to death with large rocks (pictured). His final words are recorded as "more weight."

The panic was confined to Salem

Although Salem became the most notorious, it wasn't the only part of the colonies to experience a witchcraft craze on this level. Witchcraft accusations were leveled in 24 communities in the Massachusetts Bay Area, including Charlestown, Boston, Beverly, Marblehead, Lynn, Malden, and Gloucester, per Britannica. Andover was the most severely affected, with a whopping 1 in 10 people accused. The hysteria became so widespread that even Cotton Mather's father criticized claims of bewitchment by specter (a widespread puritan belief at the time, via the BBC), saying accusations needed to be more direct to be credible.

According to the Washington Post, a chilling aspect of the accusations was that one of the girls involved in the early wave of "bewitchments" named 62 people in total, with those outside of Salem having no idea why they were incriminated. A Boston-based sailor tried to point out that he would have no reason to cast spells against people he didn't know – which didn't stop him from being convicted and sent to prison. The fact that he knew various members of the court seemed to make little difference.

In Andover, people accused their own family members, with lurid accounts of people confessing to flying over treetops to take part in satanic rituals and admitting to pledging their souls to Satan. A senior minister in Andover even found out, bewilderingly, that he was related to about 22 witches.

It was based on superstition

It's easy to see the events at Salem as an outbreak of hysteria that was a result of fundamentalism and ignorance. Yet highly intellectual figures like Cotton Mather (pictured), a Harvard graduate, child prodigy, and intellectual who was later a proponent of mass vaccination, published a book describing children in Boston being bewitched, titled "Memorable Providences."

Other learned minds in the Bay Colony, where literacy rates were high, scrutinized the religious texts, laws, and history surrounding witchcraft and adhered to their own deliberative and bureaucratic procedures. Rather than being an outburst of madness, the Salem trials followed established legal precedents. Perhaps the only aspect of standard practice that was ignored by the Salem trials was that the accusers were not asked for bonds, which demanded a financial commitment and a willingness to defend their stance in court, as described by the BBC.

Through modern eyes, Salem can seem bizarre and preposterous. Yet as academic Simon Middleton points out via the BBC (at 22.14), many people at the time did not see it this way, especially in a community dominated by Puritan theology, which stated that being persecuted was a sign of being holy, in that the devil hated you in your righteousness and would torment you through spectral witchcraft. Given the memories of fleeing European persecution were still strong, the sense of being under siege, by demonic and human forces alike, was logically consistent in the minds of a community on the edge.

Poisoning was to blame

A debunked explanation for the Salem witch trials was that the children making the accusations had eaten contaminated rye. It was based on theories by behavioral scientist Linda Caporael (via The Washington Post), who claimed that ergot (pictured), a fungus growing on grain that releases lysergic acid when it breaks down, had the same effects as LSD, and had therefore caused the hallucinations and fits experienced by the girls who made the first witchcraft accusations.

There is little evidence to back this up, as the girls' lucid mental states during the trials are not consistent with the effects of ergot poisoning, including the fact they didn't experience further physical deterioration. They also shared meals with others who did not have their experiences, while accusers who shared their visions did not all have the same physical reactions.

Another possible explanation is that the girls were suffering from an auto-immune disease. One piece of analysis from the BBC argues that anti-NMDAR encephalitis, a hereditary brain disorder, might have played a role in the girls' anxieties about persecution, spasming limbs, hallucinations, and impaired speech. However, although their symptoms are consistent with modern-day understandings of the disease, they fail to explain similar reactions among others who claimed to have been bewitched. The fact that people's physical complaints disappeared once they left the courtroom suggests to other historians that their affliction was psychological rather than physical. Like many other theories about what kicked off the tragic events at Salem, no one truly knows.

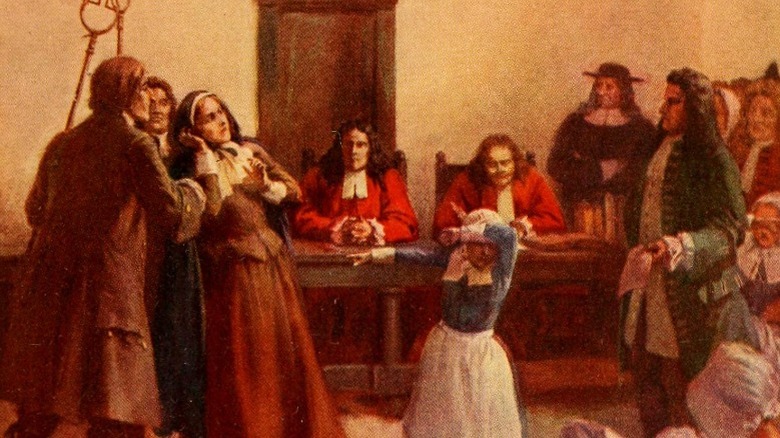

A witch couldn't overturn an accusation

A witchcraft accusation in Salem was a difficult label to shake off. Evidence couldn't be corroborated due to the Puritan belief in the existence of malignant specters, beings that could be compelled by satanic forces, such as witches, to harm godly and righteous humans. Because a witch's specters could attack people from miles away, for someone to have an alibi showing they were physically present somewhere else often counted for little, as stated on the BBC.

Yet a key aspect of Puritan theology was the sanctity of confession. Those in Salem who refused to plead guilty to witchcraft were almost always hanged, while those who confessed were likely to be let off. When they realized the inverted nature of this logic, some of the accused adopted this strategy to escape the hangman's noose. A canny example of this was the enslaved woman Tituba, who confessed to having been visited by the devil and was eventually acquitted, according to the Smithsonian Magazine. A sad example was Rebecca Nurse, whose refusal, as described by the BBC, to admit to a crime she felt innocent of ultimately led her to the gallows.

People who stayed in jail long enough could weather the storm and potentially accuse other people. Later on, it was later accepted that not everyone could be a witch, given how many were accused – particularly when they included elite members of Massachusetts society. After Salem, the authorities quashed many witchcraft accusations.

Only humans were executed

An even more bewildering aspect of the Salem witch trials was that the spillover didn't just affect people; animals could be seen as purveyors of evil magic. A number of dogs were accused of witchcraft, and at least two were killed. One was accused of bewitching a girl, while another was considered to be under a witch's spell.

According to "The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege," two of the girls in Salem afflicted by witchcraft had claimed the spirit of a man in Andover named John Bradstreet had ridden on top of a dog and caused it great torment. Despite being considered a victim of Bradstreet's malignant ways, the dog was executed. Bradstreet was forced to flee from Andover.

In another instance, a dog was killed after a girl in Andover maintained that the creature's specter was causing her afflictions. The historian Stacy Schiff highlights that in response, Cotton Mather's father, Increase Mather, had said exasperatedly that if the dog had been a demon, then it would almost certainly have been impossible for humans to kill it. The fact that it had been so easy to put the creature down clearly meant it was a normal beast. Historian Marion Gibson (via the BBC) highlighted how Robert Calef, a baptist merchant practicing a different form of Christianity to many of those in Salem, had condemned the trials and spoken derisively in his book "More Wonders of the Invisible World" of the practice of accusing dogs of witchcraft.

The hangings happened at Gallows Hill

For many years it was assumed that Gallows Hill in Salem was the execution site for those convicted in the 1692 witch trials. Yet extensive work done by researcher Emerson Baker has shown the hangings most likely happened at a spot a quarter of a mile away from the hill.

Another piece from The Washington Post looks at how this spot, the focus of one of the town's darkest moments in history, was on a ledge overlooking Salem that was visible to as many people as possible, including the houses below – likely to be a calculated act, as it would have served as both an added humiliation to the victims and a warning to others about what awaited them if they fell foul of the community. It was named Proctor's Ledge after the grandson of victim John Proctor, who knew the grisly connection his relative had to the land and decided to buy it.

As of 2016, it unassumingly resided near a branch of Walgreens. In 2017, the Smithsonian Magazine highlighted the town's decision to put up a memorial below Proctor's Ledge to the victims who died there. The day the dedication happened – July 19 – was the same date that the first mass executions in 1692 took place, resulting in the deaths of Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Rebecca Nurse, and Sarah Wildes. They and others' names have become part of the town's efforts to honor and remember what happened.

Women had no agency

Far from being ignored or belittled, the accusing girls were listened to by the more senior members of the community and came to be seen as experts in how witchcraft functioned. Other women and girls in Salem picked up on widespread anxieties about witchcraft and the presence of the devil partly because female literacy was high; many would have read Cotton Mather's book on the subject, as The Washington Post points out. The accused enslaved woman Tituba was even listened to and exonerated, albeit after a long spell in prison.

The reason for the testimonies of women being given such an unusual level of attention was largely because the chaos experienced by those in Massachusetts could be blamed on something else. The minister Samuel Parris, for example, the father of one of the original accusors Elizabeth Parris, wanted to believe he was a godly man and that the devil hated him, particularly as he was not well-liked by various warring factions of the community (per the BBC). Women were arguably the ones channeling and exercising influence in the middle of the chaos.

One overlooked aspect of life for Puritan women in Salem was that they could visit the local tavern, even if it was their only freedom in a restricted life of silence and submission. Witchcraft rumors among tavern women led to accusations that could be fatal (per the BBC). As writer Stacy Schiff highlights, previous witch trials had never before been so based on a cohort of young women.

Everyone was united against the accused

Salem was a deeply divided community. Some of the people in the village of Salem wanted to set up a breakaway church away from the bigger town of Salem, and there was a feud between the Putnam and the Porter families, who had different ideas about how religious affairs in the area should be run (per the BBC).

More widely within the colony, far from being in agreement about the trials, the events at Salem were not seen as important for a long time. As Smithsonian Magazine points out, members of the colony's provincial council were more worried about French and Native American attacks from the north, as well as epidemics of disease and the loss of their charter in 1684, which meant King James II could establish dominion over New England.

These social anxieties dovetailed well with Puritan theology, which allowed people to believe that the devil testing them was the reason for such social chaos. Yet the elites of the colony, including Governor William Phipps, pardoned people after the early wave of convictions. One seaman in Boston said that it was likely the devil was causing the accusations (per the BBC), and writers like Robert Calef wrote books mocking the defenses of witchcraft produced by Increase and Cotton Mather, saying they were an example of "Biggotted Zeal." The witchcraft convictions were ultimately not seen as something politically sustainable, and the antics in Salem were brought to an end in 1693.

It happened only to poor people

One of the more harrowing aspects of the Salem trials was that those from all backgrounds were being accused and executed (via The Washington Post). Those killed in Salem included a 42-year-old, Harvard-educated minister, a fortune-telling carpenter, and people with considerable wealth and influence like John Proctor. Rebecca Nurse, one of the first group of people to be hanged, was considered a woman of good standing in the community but fell foul of the accusations made by Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams. On the other end of the scale, the youngest accused witch was 5 years old, succumbing to insanity after spending most of 1692 in child-sized manacles.

Some scholars have suggested that the wife of the governor, William Phipps, was accused of witchcraft (via the BBC). Thomas Brattle, a wealthy merchant, further denounced the trials and publicly accused Jonathan Corwin, one of the court officials in the Salem trials, of pronouncing judgment on women in the community but not bringing his own mother-in-law (who, amusingly for modern observers, was called Margaret Thatcher) to trial when she was accused. The wife of a minister, John Hale, was accused, causing him to change his mind about supporting the trials.

In many ways, the story of Salem changed direction when the elites of the colony got involved. It ultimately led to the winding down of the trials, leading Salem in in the late 17th century to become a grim memory for later generations.