Who The Kings On Playing Cards Are Said To Represent

That traditional playing cards continue to exist and be used widely around the world in the 20th century is an indicator of the brilliance of their design. Whether for family-friendly games, gambling on games of chance, magic tricks and sleight of hand, or even telling fortunes, the traditional 52-card deck — as available in corner stores virtually everywhere — has been the source of countless hours of entertainment down the centuries. And like any truly universal innovation, the playing cards we know today have a long and complex history, with many countries claiming to have created them. As noted by The Guardian, though the most commonly available playing cards are derived from French, German, and Italian traditions, the deck's origins are also believed to lay further afield in Persia, China, and India.

Per the same source, it was French card makers — whose simple suit symbols meant that their stenciled cards could be produced more quickly than those of other card-making traditions — who most greatly influenced the card deck we know in modern casinos today. But few people know that for many years, the four kings included in the deck were also named after famous historical figures, with names printed alongside their portraits. So who are they meant to be?

The King of Hearts

Per The Guardian, the identities of the various kings in early decks of cards varied greatly in the French tradition of card-making, but from around 1553-1610, the names stenciled on French playing cards became broadly fixed. From then on, for example, the king of hearts was given the name "Charles." Though this is a common kingly name in European history, it was in reference to one king in particular: Charlemagne, also known as Charles the Great. Notably, his military might helped to stabilize the area of Europe that is today France — as well as parts of Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands — after the fall of the first Roman Empire (via History).

As noted by Britannica, Charlemagne was known as King of the Franks, a Germanic people after whom modern France is named. He became Holy Roman Emperor in A.D. 800 and ruled the continent until his death in 814. Though Charlemagne is typically depicted as bearded and mustachioed in classical portraits, the king of hearts in the modern deck of cards is 'stashless, the only one of the four kings to be so. According to The Guardian, this is believed to be due to a printing error that was then reproduced by later card makers.

The World of Playing Cards also notes that printing errors have led to the King of Hearts being referred to affectionately as the "Suicide King," as many prints seem to depict him plunging his sword into the side of his head. The Guardian notes that the sword was once an axe, but it was replaced at some point in the card's history.

The King of Spades

In the original "Paris" design set that rose to prominence from the mid-1500s onward (via "Positively Fifth Street"), the king of spades often carried the name "David" (via International Playing Card Society). But which David exactly does this card refer to? The same source claims that the David in question was the Biblical David, the second king of Israel, who lived around 1,000 B.C. (per Britannica). David is a central figure in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and his name is known even outside religious communities for the famous story of his battle with the giant Goliath, whom he defeated with a slingshot. The tale of his battle with Goliath remains the prototypical underdog story even today.

According to James McManus in his book, "Positively Fifth Street," French card makers in the Rouen tradition — who incidentally tended to feature as the king of clubs rather than hearts — would even include David's slingshot alongside the sword the card still carries, though this detail has been lost.

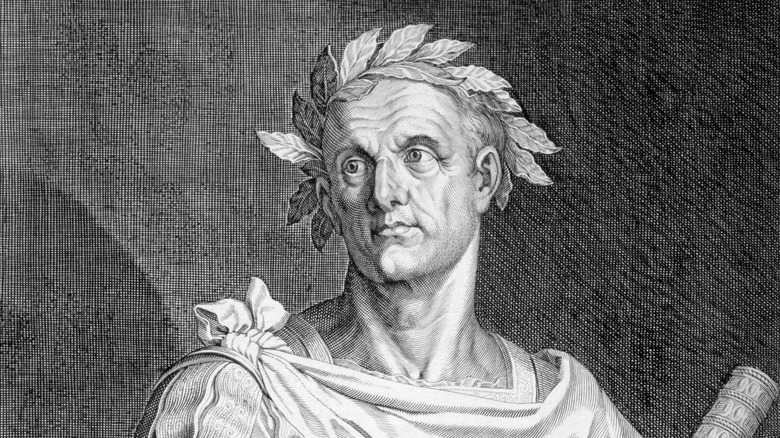

The King of Diamonds

According to "Positively Fifth Street," the king of diamonds in the named playing card decks of the 16th and 17th centuries represents Julis Ceasar (it carried the inscription "Cesar"). Through political cunning and decisive military action — his famous "crossing the Rubicon" has become a phrase in itself — the legendary Roman ruler utterly changed Europe forever (via Britannica).

As noted by National Geographic, through Caesar succeeded in uniting all of Rome — declaring himself dictator in the process — his rule was short-lived, as he was assassinated by a band of Roman politicians within a year of taking power. Although The Guardian notes that some speculated the "Cesar" on the named cards referred to another Caesar — Augustus, who was Caesar's son — it was eventually accepted to refer to Julius Ceasar.

The King of Clubs

The final king in the deck, the king of clubs, is no less prestigious in terms of the historical importance of the figure it is said to depict. Per the International Playing Card Society, French card makers named the king of clubs as we know it today after Alexander the Great and bore the name "Alexandre" alongside the iconic club symbol.

Though legend had it that Alexander the Great was a descendent of the Greek god Zeus, he was born into a prestigious royal — though human — line in the Kingdom of Macedonia in 356 B.C., according to History. Alexander claimed the throne at the age of 20 after the assassination of his father and led a life of Herculean feats of strength and bravery, as well as incredible military conquests, eventually becoming King of Persia. But despite his reputation down the centuries, Alexander the Great reigned for only 12 years, as he died prematurely young at 32.

The disappearance of names from playing cards

Despite the fact that Charlemagne, David, Julius Caesar, and Alexander the Great became the names most commonly seen adorning the upper right corners of the king cards in France in the 1500s and early 1600s, their identities would be impossible to derive from packs of traditional playing cards as we know them today. Why?

According to The Guardian, the practice of including names on cards died out in the 18th century. Meanwhile, the International Playing Card Society claims that in the 1800s, an innovation saw cards become double-ended, i.e., they would have a head at each end, as we know them today, rather than depict the bottom half of the royal portrait. As a result, they lost many of the many distinguishing features — such as David's slingshot — that linked the figures to the historical heroes they were connected to in the 1500s.