Gallagher's Initial Career Plans Were The Furthest Thing From Comedy

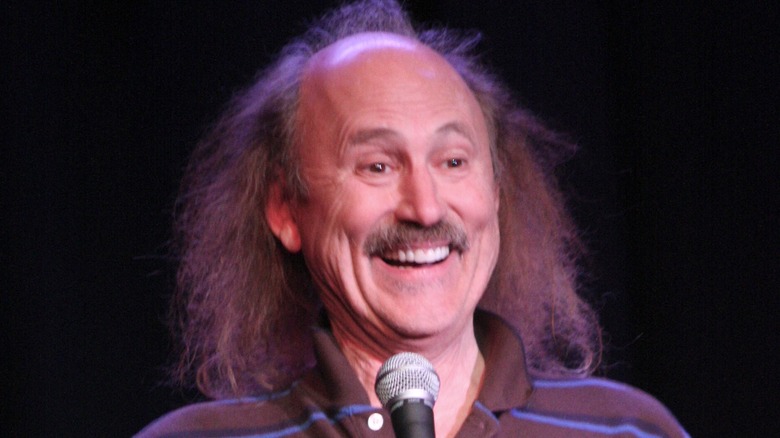

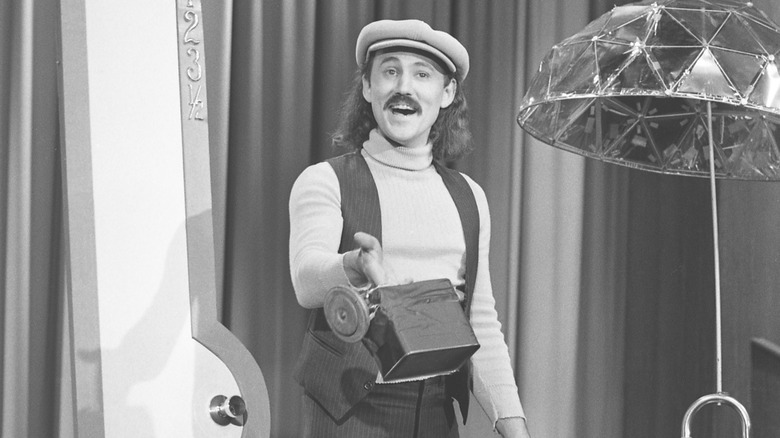

The American comedian Gallagher died at 76 on November 11, reports NBC. Leo Anthony Gallagher Jr. was famous for his stand-up bit called the "Sledge-O-Matic." On stage, he used an oversized sledgehammer to smash a variety of foods, spraying the audience with bits of apples, burgers, and even a candle-adorned birthday cake. The performance ended with a watermelon succumbing to the "Sledge-O-Matic."

His routine began as a spoof of the "Veg-O-Matic" food slicer commercials. Television ads for the product permeated the air starting in the 1960s with the famous slogan: "It slices! It dices!" (per the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History). The "Sledge-O-Matic" is Gallagher's most famous bit. But he insisted that he was equally talented in "non-smash" comedy (his name for propless comedy), wrote The Morning Call in 2008. "It's like the world only wants me to smash watermelons. It's crazy. I guess they don't know I'm a deeper pond," he told Savannah Now in 2017.

During his lifetime Gallagher performed in over 3,500 stand-up shows and put out 14 comedy specials on Showtime alone. His 1980 stand-up special "An Uncensored Evening" was the first comedy special to be aired on cable TV. He also appeared on MTV, Comedy Central, and the 2013 biblical film "The Book of Daniel" (billed as Leo Gallagher, per IMDb). Yet the man famous for his comedy began a career in another field entirely.

Gallagher, a comedian of science

Leo Gallagher, born in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, envisioned a life quite different than the one he ultimately led, writes CNN. Planning on pursuing his interests in the sciences, he attended the University of South Florida, where he earned a degree in chemical engineering with a minor in English (per Savannah Now). After graduating, he worked as a chemist at a manufacturing plant until an opportunity arose to be the road manager for Jim Stafford, a musician and comedian. Gallagher's role included writing some of the performer's material.

Soon, word spread of his joke-telling abilities, and Kenny Rogers' manager asked if he'd like a 100-night job opening for the musician. The experience was a crash course in stage performance. Gallagher remembered, "I went from nothing — I really had no experience on stage — to being the opening act in the largest auditorium in America." To survive the tour, Gallagher viewed it through a scientific lens. "I take a scientific mind to entertainment. I'm the smartest guy ever dumb enough to want to be a comedian. I like to make people's minds smile."

Gallagher initially hesitated to commit to comedy, still considering himself a scientist. He explained to Savannah Now, "I wanted to be a scientist, I didn't want to be a comedian. If I had a career as a scientist, I couldn't have people saying, 'You can't trust a guy who was a comedian.'"

By attrition alone

Thinking himself still a scientist, Gallagher offered his comedy ideas to George Carlin and Albert Brooks, but the comedians rebuffed him. "George wrote back and said he wrote all his own material. Albert never got back to me," he said (via Savannah Now). Later, Gallagher moved to Los Angeles and workshopped his act at the Comedy Store, an historic club located on the Sunset Strip, writes CNN. His big break came when he appeared on Johnny Carson's "Tonight Show" in 1975, and after his 1980 cable special, his career soared. While Gallagher did go on to great success, comedy wasn't his only departure from science. He ran for governor of California in 2003, according to The Morning Call.

Gallagher is known for his show-business longevity. "While his counterparts went on to do sitcoms, host talk shows and star in movies, Gallagher stayed on the road touring America for decades," his obituary says. "He was pretty sure he held a record for the most stand-up dates, by attrition alone."

Yet Gallagher had a darker side and was entangled in two separate lawsuits from audience members regarding physical violence. During his interview with Dave Howell for The Morning Call, he accused the journalist of asking questions worthy of a high school newspaper. ("[O]r maybe he said not worthy; I was caught by surprise," wrote Howell.) In the same interview, he told Howell, "I have lasted longer than anyone. I can do a show anywhere. I've been doing this 35 years with and without the hammer."