The Deadliest Mining Disasters In History

Mining is one of the world's oldest professions. So old, in fact, that it even predates dating things — the earliest known mine can be found in a South African coal deposit, and it's thought to be between 20,000 and 40,000 years old (via Earth Systems). This means humans may have been mining coal while Neanderthals still roamed the Earth. Who knows, maybe it was even the Neanderthals doing the mining.

No one wrote about any of the first mining accidents, because those mines literally predate actual writing (via the British Library). But there certainly were accidents — mining isn't safe now, and it certainly wasn't safe 40,000 years ago. The difference may be in the scale of destruction. Mines of the 19th century onward were, and still are, worked by hundreds of people, and cave-ins, fires, and toxic gas are ever-present threats in that deep underground world. When disasters happen, they can kill hundreds of people, sometimes not just the miners but other people who live and work in the community. Here are some of the world's worst mining disasters — Neanderthals, sorry if any of the big ones from your era got overlooked.

Los Cedros Mine

Tailings dams are structures built to contain mine tailings, which is the crushed rock and heavy metals left over after the ore is removed from a mine. The problem with tailings dams is that they're forever — they have to be maintained forever, because the toxic waste they contain lasts forever.

One of the worst mining accidents in history happened in 1937 at the Los Cedros gold mine in Tlalpujahua, Michoacán in central Mexico, when torrential rains caused a tailings dam failure that released a tailings slurry into a nearby town, destroying several neighborhoods and a historic church. According to Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, the breached dam released 16 metric tons of saturated waste, which inundated the village at a speed of 20 to 25 meters per second. It probably won't surprise you to hear that there were warning signs that a disaster was imminent in the days prior to the breach, but the mining company did not act to prevent the disaster, and authorities didn't bother to evacuate anyone living in the danger zone.

Initial reports of such disasters are often mixed — mining companies never really want anyone to know the true number of casualties, and newspapers sometimes over or underreport the number of deaths, too, especially since the numbers tend to change in the hours and days after the event. For this reason, no one is really sure how many people died in the disaster, though most sources say "at least" 300.

Chasnala Mine

To many Americans, coal can seem like a thing of the past, but in other parts of the world, it's still a pretty big deal. In 2021, coal-fired electricity was at a global high (via Visual Capitalist), which means the U.S. might be phasing the stuff out, but the rest of the world is not.

Still, the dangers of coal and coal mining are kept pretty quiet. Coal is a big industry and a lot of people depend on it, so it's best not to let everyone know how icky it actually is. A good example of this is the Chasnala Mine disaster of 1975 near the town of Dhanbad in Jharkhand, India. According to the ENVIS Centre on Environmental Problems of Mining, the disaster occurred when the 80-foot wall of coal that was the only thing standing between the active mine and a flooded mine collapsed, releasing 1,350,000 cubic meters of water. The active mine was inundated, instantly killing 375 people. They didn't drown but were pulverized — reports said the only bodies that could be identified were those that still had their cap lamps or personal items. Those that did not, remain nameless.

According to the Indian media company TFI, both the government and the mining company dismissed safety concerns and warning signs prior to the event, and the almost complete absence of Indian media coverage of the accident seems to point to an attempt to cover up the affair and eventually erase it from collective memory.

The Monopol Coal Mine

In 1946, miners were 3,000 feet underground in a German coal mine near the town of Kamen in the Ruhr when there was an explosion. According to the German mining history site Ruhrgebietszechen, safety protocols at the mine were sub-par (cost-saving measures, of course), and the tunnels were full of ankle-deep, highly-flammable coal dust. There was also methane in the tunnels, which means the miners were basically working inside a stick of dynamite. The explosion was triggered by an errant spark, which set off a chain reaction throughout the second level of the mine, sending a jet of flame out of the third shaft. The explosion was so intense that it destroyed structures within the shafts and above ground as well.

Four hundred sixty-six men were trapped inside the mine — 64 of them got out alive, and 18 bodies were recovered, but the rest were never seen again. According to "Civil Affairs and Military Government: North-west Europe, 1944-1946," 11 of the survivors of the initial blast were located the day after the disaster, but it took three days for rescuers to reach them, and by that point, only eight of them were brought to the surface alive. One man evidently managed to rescue himself, but the rest of the miners either died in the explosion or in the days that followed, still trapped inside the collapsed tunnels.

The total death count for the Monopol disaster was 405, including three men who died from injuries they sustained on the surface.

The Hwange Colliery

In 1972, there was an explosion in the No. 2 Colliery at the Hwange Coal Mine in Wankie, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Like the Monopol disaster, the explosion was sudden and violent, rocketing through every underground shaft and tunnel and releasing gigantic columns of smoke and gas that went hundreds of feet into the sky. According to the International Journal of Art & Humanity Science, the explosion filled one of the major shafts with pieces of roofing and steel girders, trapping hundreds of miners inside. Importantly, the explosion damaged the fans that brought fresh air into the mine, and it took 41 hours for work crews to complete the repairs necessary to make the air breathable.

At that point, it seemed unlikely anyone was left alive, but crews kept looking. They made new shafts to direct the fresh air down the mine shaft, towards the part of the mine where people had been working just before the explosion. Rescuers went more than 6,500 feet into the devastation, even though fires were still burning inside and explosions could still be heard. They rescued a grand total of nobody.

The explosion may have been sudden, but that doesn't mean there weren't any warning signs. Before the accident, there had already been a number of smaller methane explosions, including some large enough to collapse tunnels. The death count at the Hwange Colliery was 427.

The Coalbrook Colliery

Coal mines are especially dangerous because they tend to be full of coal dust and methane gas, an explosive combination that needs just one spark in order to become a tragedy. But coal mines — and other mines, too — can also collapse, mostly on account of them being miles underground and having an awful lot of earth pressing down on them from above.

This is what happened in 1960 at the Coalbrook Colliery in Clydesdale, South Africa. Once again, negligence played a role in the disaster. According to The Journal of The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 24 days before the major event, there was a smaller collapse in Section 10. No one died, nor did anyone think to inform a mine inspector who showed up two weeks later that there had been a collapse.

Then, less than two weeks after the inspection, there was a second collapse. The mine's manager and overseer decided it would be prudent to close off the collapsed section but, remarkably, also decided that the rest of the mine was safe. Work went on until just under three hours later, when miners were "overtaken by a hurricane of dust-laden air accompanied by crashing like thunder." The entire eastern part of Section 10 had collapsed, trapping 438 workers inside. Rescuers were able to save one man, but despite days of drilling rescue holes in an effort to reach the trapped men, none of the remaining 437 were ever seen again.

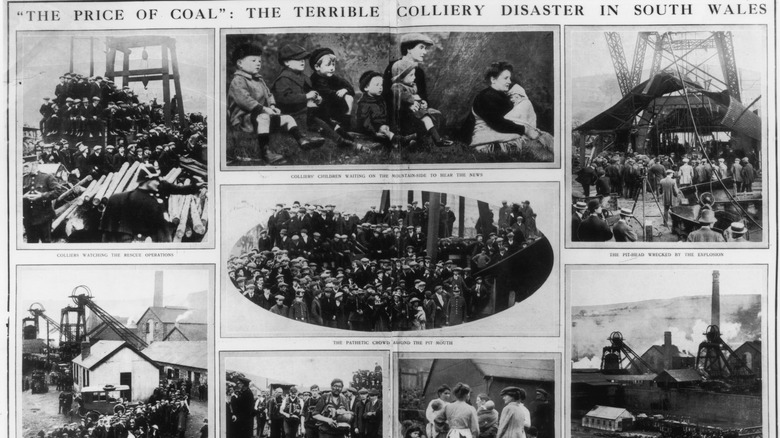

Universal Colliery

By now, you're probably starting to see a trend — big mining disasters often happen in coal mines, because coal mines aren't just a very long way underground, they're also full of toxic gasses like carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and methane. It's not safe to breathe any of these gasses, and it's much less safe when these gasses cause explosions — which are made even worse when flammable coal dust ignites. And let's not even talk about black lung disease, which is one of the long-term hazards of working in a coal mine, because that's a whole 'nother Oprah.

According to the BBC, the worst mining disaster in Britain happened in the small Welsh village of Senghenydd in 1913. On an October morning, the Universal Colliery was rocked by a methane explosion large enough to launch a two-ton cage up the mine shaft. There were 950 miners working in the pits that day; those on the east side got out safely, but those on the west side burned to death (via The National). The last 18 survivors weren't brought out of the rubble until two weeks after the explosion, and the last person to die in the disaster was one of the rescuers.

As is so often the case, the men who died in the explosion were fathers, husbands, and sons. Sixty of them were still in their teens, and eight were just 14. The total death toll: 440.

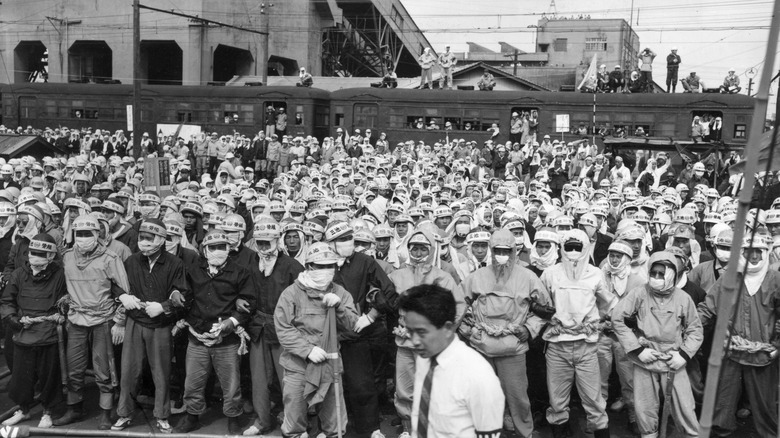

Mitsui Miike Coal Mine

The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine has always been kind of an unsavory place. According to the Asia-Pacific Journal, it was once a World War II POW camp, and for a while, its operations depended on Chinese and Korean forced labor. It was also the site of one of the biggest mining disasters in history. On November 9, 1963, mining carts laden with coal were making their way to the surface when one of them derailed. A chain snapped, which loosed eight more coal-filled cars. The cars rolled backward down the track, picking up speed, then they derailed, too. Somewhere, there was a spark, which ignited the coal dust that had been kicked up into the air and caused a series of two explosions and a wind blast that traveled more than 3,000 feet per second toward the surface (via United Nations University).

Just 20 people died in the explosion, but the blast forced massive amounts of carbon monoxide throughout the mine, and an additional 438 died as a result of breathing the poison gas. Another 839 became ill but survived.

It was the 1960s, which isn't exactly the pinnacle of human technology, but for some reason, the mine's owners were completely ignorant of the fact that coal dust can ignite without the presence of methane gas. In other words, they genuinely believed their mine was safe because there was very little methane in it, and 458 people paid the ultimate price for their ignorance.

Besshi Copper Mine

Most of the most horrible mining accidents — that we know about anyway — happened during the 20th century, when industrial activity was picking up and regard for employee safety was low. But at least one major mining accident predates the 20th century (if only by a year). And unlike many of the others on this list, this one did not happen at a coal mine, but at a copper mine.

Copper smelting requires heat, and to create heat, you need fuel. According to the Sumitomo Group Public Affairs Committee, for more than 200 years, the company that owned the Besshi Copper Mine in Japan deforested the nearby mountains in order to obtain charcoal to operate the smelters. But that's not all — the smelters polluted the air with sulfuric acid gas, which came back down to Earth as acid rain, killing what few trees remained.

In 1899, a typhoon swept the area. Without trees to stabilize the earth, the mountainside came down and a landslide destroyed the active mining facilities below. Details about the incident are scarce, either because it happened during a time when record keeping wasn't that great, or because the Japanese government didn't want anyone to remember the details. One thing that isn't in dispute, however, is the death toll. Exactly 512 people perished in the Besshi Copper Mine disaster (via the Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering). In the 100+ years since, the copper mine has been closed and a reforestation campaign has restored the mountains.

Laobaidong Colliery

It's never been especially easy to get communist countries to talk openly about the terrible things that happen within their borders. In 1986, most of the world's powers knew something very big and very nuclear had happened in Ukraine on account of all the radioactive fallout, but the Soviet Union was notoriously mum about the accident at Chernobyl for days after it occurred (via New Scientist).

The same thing happened when 682 people were killed in China's Laobaidong Colliery in 1960, except there wasn't any nuclear fallout to warn everyone that something was going on. According to China Security, the Chinese government classified the accident as a "state secret" and didn't talk about it for more than 30 years.

The Laobaidong Colliery disaster was another methane gas explosion, like so many other coal mining accidents. Details seem pretty scarce, but the China University of Mining and Technology says an investigation determined that the plant had been exceeding production quotas by 59%, and there were no real safety protocols in place to ensure that the busy plant was a safe place to work.

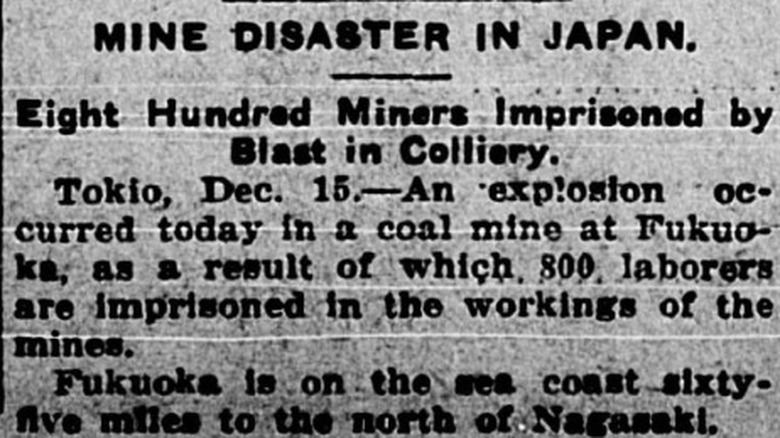

Mitsubishi Hojo Coal Mine

The Hojo Colliery on the island of Kyushu was one of the most productive coal mines in Japan, with an annual output of 230,000 tons. According to "Cartographic Japan: A History in Maps," a 1914 explosion at the Hojo Colliery filled the upper ventilation shaft with debris, completely blocking it, and although the lower ventilation shaft was clear, the equipment struggled to remove the poisonous gasses out of the mine. It was hours before the air was clean enough to make entry possible, except that it wasn't clean enough because four rescuers died of carbon monoxide poisoning while attempting to pull bodies from the wreckage. There were so many dead that observers described them stacked up "like cordwood," and, even more horribly, "baked like sweet potatoes."

An investigation found that the coal dust explosion had been triggered by a faulty safety lamp (yes, a "safety lamp"). Evidently, the mesh that was supposed to keep coal dust away from the flame didn't actually keep the coal dust away from the flame, and the result was 687 deaths, including the owner of the lamp and his wife, who worked with him in the mine.

Some of the miners trapped below when the explosion happened were burned alive, and the rest of them suffocated — not just on poison gas but on air that was devoid of oxygen on account of it all getting sucked out in order to feed the flames.

Courrieres Coal Mine

The Courrieres Coal mine in northern France was a massive thing — so massive that there were entrance tunnels in several different towns. The mine employed more than 2,000 people, including children. On March 9, 1906, a fire broke out in one of the pits about 900 feet underground. The workers couldn't snuff it, so they decided to just shut all the doors and vents so it would burn itself out. Then, incredibly, work in the rest of the mine went on as usual.

Well, surprise, the next day, there was an explosion so massive that it blew the roof off of a mine office on the surface, killing some of its occupants. According to History, the fire spread throughout the mine, making it impossible for rescuers to get inside. Trapped miners died when the infrastructure inside the mine collapsed, suffocated from poisonous gasses, or burned to death. Forty would-be rescuers were also killed when the shaft they were descending caved in.

The search lasted only three days, even though there were still survivors below. According to Britannica, one group of survivors made their own way out of the mine 20 days after the explosion, which wasn't a great look for the mine's owners. The total death toll: 1,099.

Benxihu Colliery

The Benxihu Colliery explosion of 1942 remains the biggest mining disaster in the history of the world. According to the Australasian Mine Safety Journal, the mine was located in northeastern China, but it was controlled by the Japanese, who didn't care much about the health and safety of the Chinese miners who worked there. When a fire broke out in April of 1942, management decided to seal off the afflicted area and starve the fire of oxygen. Since they didn't evacuate everyone first, this meant that the fire wasn't the only thing that suffocated.

It wasn't just a few errant workers who hadn't gotten the memo about the fire, either, it was 1,549 people. An investigation into the accident found that most of the dead had not been burned; instead, they'd died from suffocation and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Incidentally, Chinese mines currently account for about 80% of all the world's mining deaths (via AP), so maybe some changes still need to happen, China.