Virtual Reality Technologies That Failed Hard

These days, there's big money in 1990s nostalgia. Many of the pop culture fads of that decade have reemerged in new forms (like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, The X-Files, and the godawful Fuller House). The world of tech isn't immune from the nostalgia bug either, as proven by the renewed interest in virtual reality, or VR, that began in earnest with the successful crowdfunding of the Oculus Rift (and its subsequent purchase by Facebook for a cool $2 billion).

Since then, tech companies from Sony to Valve have announced their own VR headsets. Virtual reality technology, however, has had many false starts over the years. It seemed like every video game company took a shot and ultimately failed at VR technology in the 1990s. Here are a few virtual reality technologies, all from the 1980s and 1990s, that were either met with consumer indifference or simply never became a reality—virtual or otherwise.

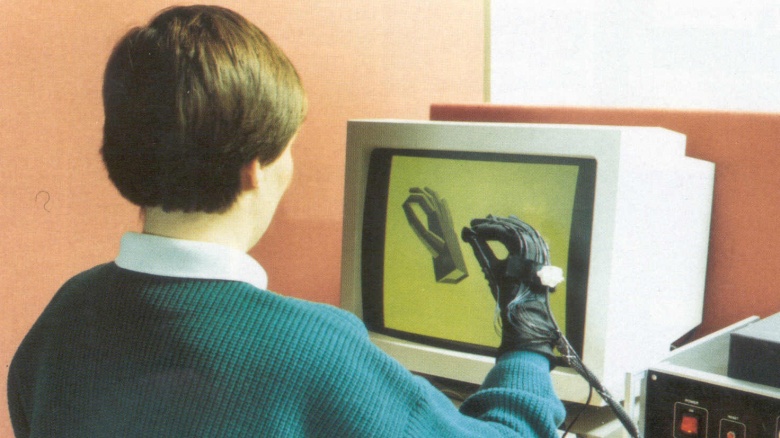

VPL DataGlove

The term "virtual reality" was popularized by Jaron Lanier, an ex-Atari employee who, along with his colleague Thomas Zimmerman, founded VPL Research in the 1980s. His new company was the first to develop consumer-grade virtual reality devices. Among them was the VPL Dataglove. The glove made a bit of a smash when VPL released it in 1987. It even graced the cover of the October 1987 issue of Scientific American. The device was a neoprene glove fitted with optical sensors and fiber optic cables. The obvious idea, other than cyberpunk cosplay, was that the user could control video games and other computer applications with their hands. Unfortunately, computer technology simply wasn't at a level in the late '80s to make this an attractive option. The glove was often inaccurate and had to be constantly recalibrated. VPL filed for bankruptcy in 1990 despite selling several million gloves to Mattel.

Nintendo Power Glove

In 1989, Nintendo released the Power Glove peripheral for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Theoretically, the glove allowed players to control their NES games by making specific movements with their hand. The hype around the glove reached a fever pitch when it appeared in the Nintendo movie/advertisement-in-sheep's-clothing, The Wizard. The unlucky kids who received it for Christmas that year soon realized that the device did not work as advertised. The glove barely functioned with the the few games that Nintendo designed for it. Also, forget about playing Super Mario Bros., Ninja Gaiden, or any of your other favorite NES games with any sort of precision. Eventually kids ripped it off their arms in frustration and grabbed the nearest controller. The Power Glove taught a generation of us to be cynical about new technology. Thanks, Nintendo.

Sega VR

Like a gluttonous corporate vampire, Sega tried to squeeze the last drop of life from its successful Genesis console in the early 1990s. Examples include the Sega CD and 32X expansions for the system. Another attempt was the Sega VR, which sought to give Genesis players an immersive virtual reality experience. The device was a LCD-equipped visor that you wore over your eyes. The band that went around the back of your head also contained stereo headphones. Sega teased the peripheral at the Consumer Electronics Show in 1993 and the device consequently received a lot of media attention from video game magazines. Sega stated they were developing four games for the VR and it would cost $200. Consumers never saw it though. The reasons behind its disappearance are murky, but it seems Sega shelved it due to poor graphical performance and complaints by users of headaches and other ailments. Alas, our dreams of playing Sonic the Hedgehog on the Genesis in glorious virtual reality—while occasionally vomiting—are hitherto unrealized.

Virtuality

The company, Virtuality, decided to cash-in on the VR craze in the 1990s by designing arcade games. These usually took the form of LCD-equipped helmets that the player would wear to interact with the game universe. Among the most popular of these game was Dactyl Nightmare. It was an early multiplayer, first-person shooter in which the players could destroy their rivals and the titular pterodactyls. While the arcade versions of Samurai Showdown or Killer Instinct may cost two quarters to play, the Viruality machines averaged at five bucks per session. The company even designed a prototype device, called the Jaguar VR, for Atari's ill-fated 64-bit console. Atari cancelled the project, however, shortly after showing it to the public at the Electronic Entertainment Expo in 1995. Ultimately the proliferation of advanced home consoles like the Sega Dreamcast and Sony Playstation is what felled Viruality's fortunes, and arcades as a whole.

The Virtual Boy

The Virtual Boy may go down in history as Nintendo's most spectacular failure. The gaming console, released in 1995, was essentially a set of heavy, red goggles that sat on a tripod. The player could look the goggles and 3D-projected games. The first problem is that the hardware only displayed red and black graphics—not exactly awe-inspiring virtual reality. The second problem was that prolonged use of the Virtual Boy could cause neck and eye strain. The system's poor sales meant Nintendo only released 14 games for it in the United States. We all still live in fear that playing the Virtual Boy back in middle school might cause latent brain tumors to develop. The one small consolation is that we got to play a Virtual Boy-exclusive Waterworld video game. Just kidding. It's bad too.

Tiger R-Zone

What's worse than the Virtual Boy? A Virtual Boy knock-off. Tiger Electronics notoriously released cheap, portable, LCD video game systems onto the market. The stilted, bottom of the barrel graphics made your NES look like a PlayStation 4 by comparison. In 1995, Tiger released its own virtual reality headset, the R-Zone, for approximately $30. This console was simply a head strap with a screen attached to it. Essentially it's like having red-hued Tiger Electronics game displayed inches away from your now strained retina. Aside from the awful graphics, sound, and abysmal games, the notable problem with the R-Zone was that the screen only covered your right eye. This design forced players to close or cover their left eye in order to focus on the screen. Much like the Virtual Boy it sought to emulate, the R-Zone failed in the marketplace. Presumably Tiger stopped production of the system before the CDC could label it a health hazard.

I-Glasses

The company Virtual I/O released a product called the I-Glasses in 1995 (seemingly the year for failed virtual reality devices). The I-Glasses were a LCD mask that looked and functioned similar to the aforementioned Sega VR device. The user wore the headset to play computer games and watch movies. If you wanted to watch your laserdisc copy of Big Trouble in Little China with Kurt Russell only inches away from your face, then the I-Glasses were your ticket. The I-Glasses likely didn't catch on because of the $600 price tag. Plus,

if you wanted the head tracking capability for your PC, then it the expansion module brought the total cost to almost $800. Why would gamers in 1995 bother playing Doom with these goggles when a simple monitor would suffice? The answer: they didn't.