Why Marie Curie's Nobel Prize Win Was So Significant

Born in Poland in 1867 but naturalized French, Marie Curie (born Maria Salomea Skłodowska) has become a household name today. But long before she became an astounding scientist, Marie Curie was a curious child with a great memory and a love for learning — perhaps partly due to the influence of his father, a mathematics and physics teacher (via Britannica).

Still, it wasn't an easy path. Women at the time weren't allowed to enter Russian or Polish universities, so she found work as a governess (per Atomic Archive). It wasn't until she moved to Paris that Marie Curie was allowed to join a university — the prestigious Sorbonne — and follow her passion to study chemistry and physics. She would eventually become the university's first female teacher.

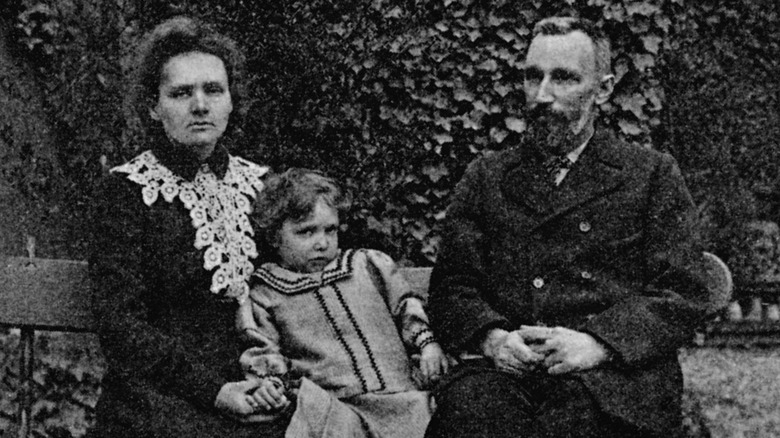

By the time she was 26, she was already working at a research laboratory, and a year later she would meet Pierre Curie, who would not only become her husband but also her research partner. After scientist Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity in 1896, Marie Curie and her husband focused their research on this and soon discovered the elements of polonium and radium (per Nobel Prize). Even then, the road for the couple was hard and most of Marie Curie's lab work was done for free as she worked on her doctoral thesis and her husband sustained the growing family (their first daughter was born in 1897), according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Focusing on groundbreaking work

Building on the work of Becquerel and Wilhelm Röntgen (who in 1895 had discovered X-rays), Marie Curie dedicated the next few years of her life to the study of uranium and understanding the spontaneous radiation caused by it. The Curies finally isolated polonium and radium and Marie called the elements "radio-active" — the name they are still known by today, as reported via Smithsonian Magazine.

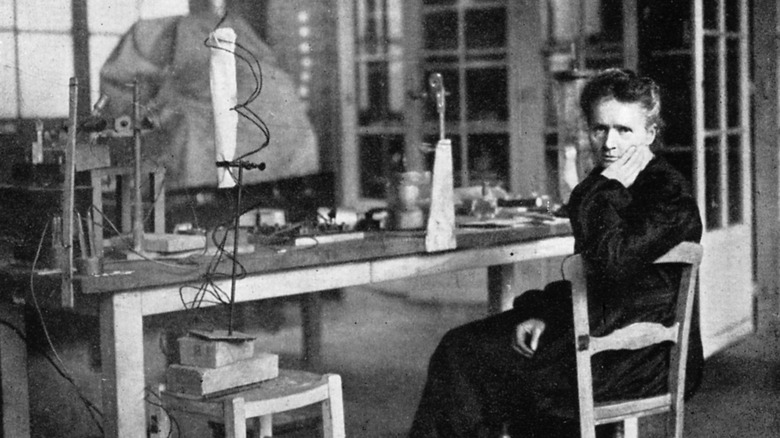

Marie spent years working in a lab with a poor setup, without proper ventilation, and without access to the material and tools needed to properly isolate and study the new radioactive elements she had discovered. The fact that she was able to continue her work in these circumstances — and despite getting sick more and more frequently because of the exposure to radiation — was already a remarkable achievement, Smithsonian Magazine points out.

When she finally presented her thesis on radiation at the Sorbonne in 1903, she became the first woman in the entire country to ever receive a PhD in physics. That same year, her husband and Henri Becquerel were nominated for a Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on spontaneous radiation, but Marie was ignored because she was a woman. It took a lot of push from within the nominating committee for Marie to be added to the nomination. The three scientists won, and Marie Curie became the first woman ever to be awarded a Nobel Prize (via American Institute of Physics).

The work continues

The Nobel Prize had a big impact on Marie's work. The money that came with winning helped improve the lab and the couple was able to hire an assistant, though it also made them into celebrities and for a while ruined their productivity (per American Institute of Physics).

Unfortunately, Pierre Curie lost his life after being struck by a horse-drawn wagon in 1906, and Marie was forced to pick up the pieces and continue on with her work while raising two daughters. Inspired by her work and talent, the Sorbonne invited Marie to take over the class her husband had been teaching for years, and months after his death she did just that, becoming the first female professor at the Sorbonne, as reported by the American Institute of Physics.

Marie didn't abandon her research, though, focusing on isolating radioactive elements, eventually isolating pure radium and proving it was an element that belonged in the periodic table (via American Institute of Physics). She succeeded and in 1911 she won a second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, for her work discovering polonium and radium, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The discovery wasn't just impressive scientifically, but it had also opened many doors in medicine. When World War I broke out in 1914, Marie Curie, accompanied by her daughter Irène, would set up the first military radiology centers, saving countless soldiers' lives by helping doctors identify the location of bullets or broken bones (per American Institute of Physics). She remains the only woman in history to be awarded two Nobel Prizes in two different science fields.