The Spider Killer: The Chilling True Story Of The Man Who Terrorized Iran

The protests across Iran in the wake of Masha Amini's death at the hands of morality police have brought fresh international attention to the plight of women under the current regime. Demonstrations have been ongoing since September and have included a display of solidarity by Iranian players at the World Cup — an action that, as noted by The Guardian, carried a heavy risk of retaliation from state actors. But oppressive policies and fundamentalist rhetoric has long bred a hostile environment for women in Iran, and has at times inspired horrific episodes of violence.

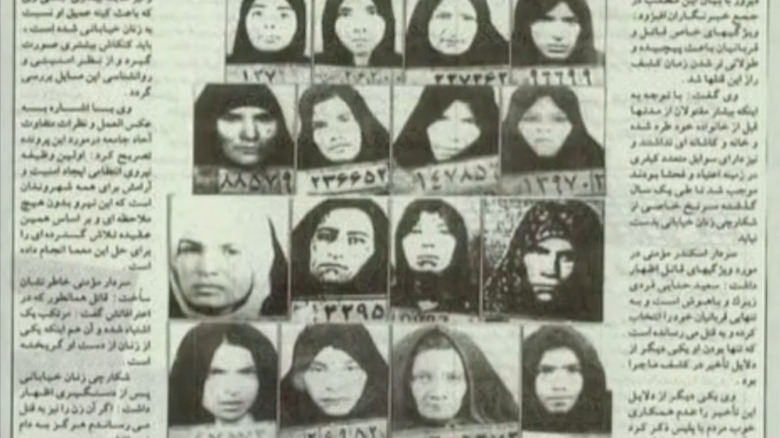

Earlier in 2022, one such instance was brought back to the country's, and the world's, attention via a film. Per IranWire, "Holy Spider," Ali Abbasi's thriller about a female journalist's investigation of a serial killer, received a seven-minute standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival. The journalist character is fictitious, but the killing spree she investigates in the film is ripped from the headlines of Iran circa 2000 and 2001. In that time, 16 women, all of them involved in the sex trade, were killed by a figure the press labeled the Spider Killer.

The murderer's real name was Saeed Hanaei, and he remains the most notorious serial killer in modern Iranian history. His crimes, and the disturbingly split reaction to them among Iranians, have been the subject of three films and considerable discourse among the Iranian diaspora.

Saeed Hanaei may have been abused as a child

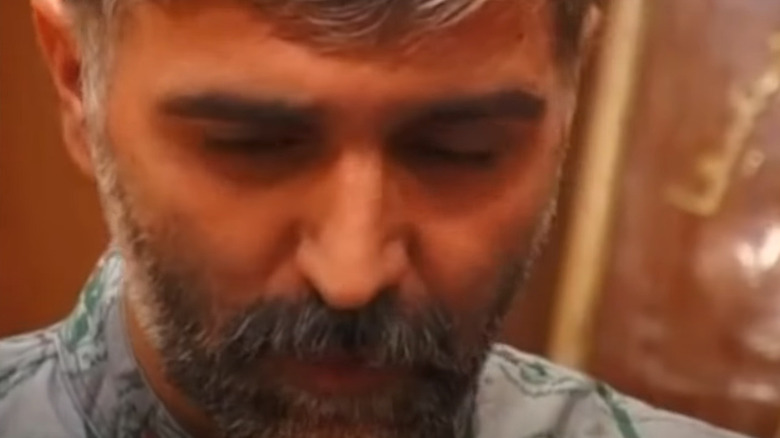

In assessing Saeed Hanaei's character, filmmaker Maziar Bahari, who directed the documentary "And Along Came a Spider," told The Guardian, "He is basically a terrorist. He's not as technologically advanced as some, but the result is the same." Journalist Roya Karimi Majd, who conducted an interview with Hanaei for the film, offered a slightly different portrait 20 years later. She told IranWire (a news outlet founded by Bahari), "Saeed Hanaei was a very simple and honest person but not very intelligent." Majd considered him a religious zealot who made no effort to deceive anyone about his actions and motives.

In interviewing Hanaei, Majd noted some unprompted recollections that Hanaei offered up. Among them were claims of physical abuse by his mother when he was growing up. He said that his mother would dig her fingernails into his skin so hard that they left marks. In another claim, he said that she sometimes tried to bite him and would have taken flesh off had she succeeded.

These allegations weren't included in "And Along Came a Spider," though Hanaei's mother and brother were among the interviewees. The New York Times, in its contemporary review of the documentary, found the mother particularly unsettling, as she made violent remarks of her own targeted at young women who used public telephones to arrange dates. But IranWire suggested that such abuse as Hanaei claimed in the cut footage could indicate something about his state of mind.

He kept up a normal family life

Saeed Hanaei was an unassuming figure in 2000. Per the Los Angeles Times, he was a husband and father of three children who earned his living as a building contractor. (Other sources, including The New York Times, list his job as construction worker.) He was a veteran of the Iran-Iraq War and was the idol of his teenage son, Ali (pictured above). Translator Ece Eroglu, who subtitled the documentary on Hanaei, "And Along Came a Spider," in Turkish, told IranWire that there was nothing sinister in his reputation.

Hanaei would later tie elements of his past and home life into his killing spree. The Guardian, following the lead of "And Along Came a Spider," reported that the spark to set Hanaei off was an incident where a taxi driver mistook his wife for a prostitute. A religious zealot and patriot, he was firmly convinced that to rid Iranian society of supposed degenerates was a public good and an extension of his service in the Iran-Iraq War. After an initial effort to target the clientele of prostitutes got him a beating, Hanaei went after the sex workers themselves.

After his arrest, one of Hanaei's most vocal supporters was his young son. Ali unsettled director Maziar Bahari, translator Eroglu, and Guardian writer Dan De Luce with his full-throated defense of what his father had done. He dismissed his feelings of grief as childish and predicted his father's work would be taken up by others, possibly himself.

His epithet came from the way he disposed of his victims

Prostitution was a fact of life in Iranian cities like Mashhad in 2000, but one long ignored or denied by state and society. High unemployment and an opium crisis helped encourage many women to take up sex work to make ends meet. The Guardian credited the Spider Killer crimes with forcing a limited public reckoning of the issue, though sympathy and recognition of the humanity of the victims remained limited in certain media and government circles.

The press took up the epithet "the Spider Killer" after a pattern had emerged in the killings but before Saeed Hanaei was identified and arrested for them. According to the Los Angeles Times (via SFGate), each victim was killed with a scarf tied in two knots pulled against the right of their necks. After killing them, Hanaei would wrap them in their own chadors, or full-body cloaks, and leave them on the streets or in open sewers. The resemblance to insects wrapped up in a spider's cocoon led to the killer's media moniker.

The atmosphere of fear inspired by the killings was marked. Hostility to sex workers in Iran, particularly in a city with such religious significance as Mashhad, meant there was little appetite for a thorough and speedy investigation. The bodies went unclaimed; their families were too ashamed, or too afraid, to acknowledge them. And sex workers who remained active in Mashhad sold their services for as little as $5.

The murders sparked conflict between reformers and fundamentalists

Before any suspects were named and arrested, the Spider Killer's identity was a topic of pitched speculation. The Los Angeles Times (via SFGate) reported one theory that the murders were an effort by religious fundamentalists to undermine confidence in Mohammad Khatami, then the president of Iran. Khatami won office with a reputation as a reformer, and his election led to a considerable rise in tensions between moderates and conservatives in government and the media. With the city of Mashhad being a traditionally conservative area, and its local authorities contemptuous of the victims, suspicion against reformers' rivals ran high. One of Khatami's supporters in the Majlis (Iranian parliament) insinuated that there might be more than one killer, working together in a conspiracy against his party.

There was a precedent conspiracy theorists could point to. In 1996, former intelligence agents hatched a plan to kill four people, for which the ex-agents received the death penalty. Ultimately, such fears proved unfounded; the killer, Saeed Hanaei, had no accomplices and was not party to a larger plot. But his trial and reputation continued to be a proxy battle between conservatives and reformers within Iran. Professor Jamsheed Akrami of William Paterson University told the Los Angeles Times that the 2002 documentary on Hanaei, "And Along Came a Spider," allowed its makers to criticize religious authorities in Iran without running afoul of censorship. And director Maziar Bahari bemoaned the return of conservatives to power after Hanaei's trial and execution.

Saeed Hanaei framed his murders in religious terms

Saeed Hanaei killed 12 women, all of them prostitutes and many with drug issues, before an epiphany came to him. The city of Mashhad was experiencing a drought at the time. Once he had dispatched his 12th victim, per the Los Angeles Times, a rainstorm came. Hanaei took this as a sign of God's favor. Freshly inspired, he brought his victim count up to 16 before he was finally caught (16 by his confession; he was suspected in 19 murders). "Had I not been arrested," he told journalist Roya Karimi Majd, "I'd have wanted to kill 150 of them" (per IranWire).

Majd and translator Ece Eroglu (also per IranWire) were struck by the genuine conviction of Hanaei that he was helping to bring on a better world. He made no effort to mask his contempt for his victims. "They were as worthless as cockroaches to me," Hanaei told the Iranian press (via The New York Times). "Toward the end, I could not sleep at night if I had not killed one of them that day." Prostitutes, in his mind, were a poison even in as religious a society as Iran.

Maziar Bahari, for whose film "And Along Came a Spider" Majd interviewed Hanaei, saw such appeals to religion as an excuse. "There are many people who are more conservative than he is and cannot even kill an animal," he told the LA Times. "You have to be a killer first."

Parliament took up the case

Investigation into the Spider Killer case was slow and limited. A deputy governor general of Khorasan province, where the city of Mashhad is located, professed more outrage at prostitution and extramarital sex than the murders, though he condemned the crime itself (via SFGate). In Tehran, the killings forced the government to at least show some recognition of the growing tide of prostitution and drug use in Iran and the forces driving their rise. But when the death toll reached nine and the response was deemed inadequate, the Majlis (Iranian parliament) sent a special investigative squad to Mashhad on April 1, 2001.

Investigators pursued three possible theories: a conspiracy of religious zealots, a political conspiracy aimed at the government, or a lone killer. Per ABC News, they also sought a possible connection between the "spider murders" and an earlier spree in Bojnourd targeting brothel owners. AP reported that, as a precautionary measure, 500 sex workers were relocated.

The Spider Killer himself, Saeed Hanaei, was finally arrested in July 2001; per The New York Times, a prostitute suspicious of his intentions escaped from him after an altercation and reported him to the police. Hanaei made no effort to deny his crimes. He told reporters he had killed the women to cleanse Mashhad, considered a holy site in Shiite Islam, and detailed how he collected victims in his car or motorcycle on nights his family was away from home.

Saeed Hanaei had considerable support within Iran

When the Spider Killer was identified as Saeed Hanaei, there was public outrage. "Most of the people in Mashhad were repulsed by these killings," filmmaker Maziar Bahari told a reporter while promoting his documentary "And Along Came a Spider" (via the Los Angeles Times). But reactionary forces in Iran's media and government had stymied investigation of the murders (per SFGate); now, they put on a highly visible show of support for the killer.

The Guardian pulled an example of such support from the pages of conservative Iranian newspaper Jomhuri Islami. "Who is to be judged?" the paper wrote. "Those who look to eradicate the sickness or those who stand at the root of the corruption?" Hanaei's brother said that his victims weren't human, his son called him a martyr and a hero, and ordinary citizens in Mashhad applauded his actions. Their defenses echoed Hanaei's own rhetoric in public statements and in his interview for Bahari's film.

The shows of solidarity with the Spider Killer faded after more details of his crimes came to light. For all his denouncements of sex workers as corrupting scum and insects, Hanaei availed himself of their services despite his marriage, according to The New York Times. He had sex with 13 of his victims before murdering them, and was guilty of other crimes besides. But Ansar-e Hizbollah, a conservative paramilitary force, continued to put the blame more on sex workers than the man who targeted them for murder.

He was interviewed for a film before being executed

Maziar Bahari was born in Iran but left for Montreal during the Iran-Iraq War (per the Los Angeles Times), only returning after the election of President Mohammad Khatami. According to IranWire (which he founded), he was working for Newsweek as a reporter covering refugees from the War in Afghanistan when he went to Mashhad and came upon the Spider Killer story. Saeed Hanaei had already been captured and tried at the time, and Bahari was fascinated with the story. This led to his 2002 documentary, "And Along Came a Spider."

A mutual friend put Bahari in contact with journalist Roya Karimi Majd, and the two secured interviews with the families of Hanaei and his victims in short order. A word with the judge assigned to the case also granted them a highly unusual interview with the killer himself, conducted by Majd. She and Bahari found Hanaei forthright and unrepentant.

Saeed Hanaei was sentenced to death by hanging, a sentence that was carried out on April 18, 2002, according to The New York Times. Footage of Hanaei's dead body swinging from the noose was included in "And Along Came a Spider" (per the Times' review). Not included was the incredulity he showed at actually facing justice. Bahari told The Guardian that, after the publicity surrounding his trial and the support voiced by conservative elements in society, Hanaei was sure he would be rescued and couldn't believe it when the noose tightened.

Saeed Hanaei wasn't the only serial killer active in Iran at that time

Largely thanks to the 2002 documentary "And Along Came a Spider" (per IranWire), Saeed Hanaei has remained the most notorious Iranian serial killer. But he was only one such figure to plague the country between the 1990s and early 2000s. Gholamreza Khoshroo, active in the '90s, was dubbed the Night Bat by the media. He raped and killed nine women before being brought to justice in 1997. Like Hanaei, he was executed by hanging.

1997 also saw the execution of another killer with a similar nickname. Ali Reza Khoshruy Kuran Kordiyeh was known as the Tehran Vampire, according to AP. A taxi driver by trade, Kordiyeh went on a three-month spree of rape and murder that, like Khoshroo's, claimed nine victims before the end. Kordiyeh seemed repentant when he was sentenced to death, but that did nothing to quell the anger of the mob that watched his execution. He was whipped by male relatives of his victims and hanged from a construction crane on the site where he caught the women he killed.

Three years after Hanaei's execution, another serial killer faced a comparable sentence to Kordiyeh. Mohammad Bijeh, according to the BBC, was given 100 lashes and a hanging for the sexual abuse and murder of at least 20 young boys in Pakdasht. (Some sources put Bijeh's victim count at more than 40, per IranWire.) Bijeh had an accomplice to his crimes, Ali Baghi; he escaped the noose but was given 15 years.

He inspired three films

The story of Saeed Hanaei has endured in Iran and disseminated around the world through "And Along Came a Spider," the documentary produced by Maziar Bahari. But his is only the first of three films that the Spider Killer has inspired. The others, per IranWire, are 2020's "Killer Spider," directed by Ebrahim Irajzad and made in Iran, and 2022's "Holy Spider," directed by Ali Abbasi and an international co-production shot in Jordan. Unlike "And Along Came a Spider," the latter two movies are dramas inspired by true events.

Of the two narrative films, "Holy Spider" has garnered more global recognition, having screened at the Cannes Film Festival. Bahari, who was sent the script for the film before production, considered it impossible to make within Iran itself under the current regime. "Holy Spider" invents a fictitious female journalist who pursues the spider murders as Hanaei carries them out and contrasts the misogyny she faces from authorities with Hanaei's self-assurance (per a BFI review).

"Holy Spider" picked up a standing ovation at Cannes and largely glowing reviews, but some found the film's heavy focus on Hanaei's perspective unsettling in the wrong way. Vulture compared it to Netflix's "Dahmer — Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story" and argued that the voyeuristic aspect of such productions regularly overwhelmed attempts at more profound statements.