Facts About The Biggest Geomagnetic Storm Of The 20th Century

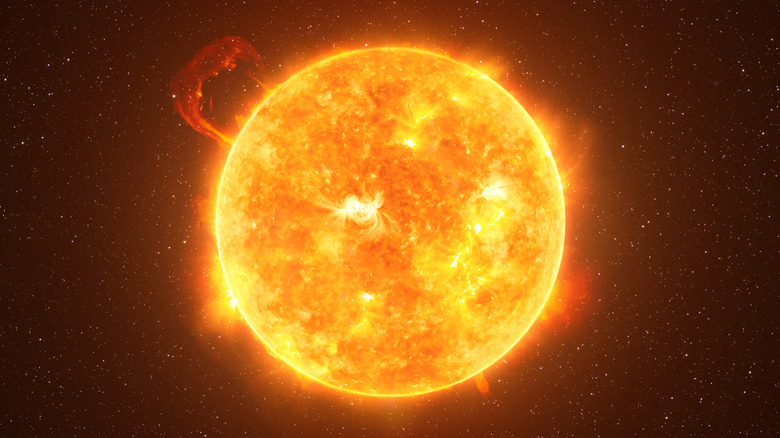

The sun often throws tantrums and ends up spewing gobs of plasma into space. Many of them are directed away from Earth. However, when solar vomitus does come hurtling toward us, it can cause geomagnetic storms that result in power outages all over the planet.

Geomagnetic storms can be caused by solar flares or much more fearsome coronal mass ejections (CMEs). It was a CME that set off what is often considered the worst geomagnetic storm to shock Earth during the 20th century: the Great Storm of 1921, also known as the New York Railroad Storm. While auroras lit up the sky, there were outbursts of fire on Earth, where charged plasma began to fry telegraph lines and switchboards. Radio signals also suffered (though some received a surprising boost). This cataclysm may have even rivaled the infamous Carrington Event of 1859 — which is thought to be the most intense geomagnetic storm of all time.

While events like this are supposedly rare, they could really strike whenever, like the CME that narrowly missed Earth in 2014. NASA thinks it could have been even more monstrous than the fires and auroras of 1921 if it had hit Earth. While the New York Railroad Storm might seem like an anomaly, nobody really knows what might come for us in the future.

It was set off by several coronal mass ejections

There have been worse solar storms that belched plasma away from Earth, but this one was the most severe that ever hit our planet during the 20th century.

Evidence suggests that what is now known as the Great Storm of 1921 or the New York Railroad Storm of 1921 was ignited by one coronal mass ejection after the other, as researcher Mike Hapgood states in his study on the event, published in the journal Space Weather. Coronal mass ejections are not just monster solar flares. According to NASA, solar flares are powerful plasmatic explosions that push charged particles toward the sun's surface, while coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are great gobs of plasma ejected from its outer atmosphere — the corona.

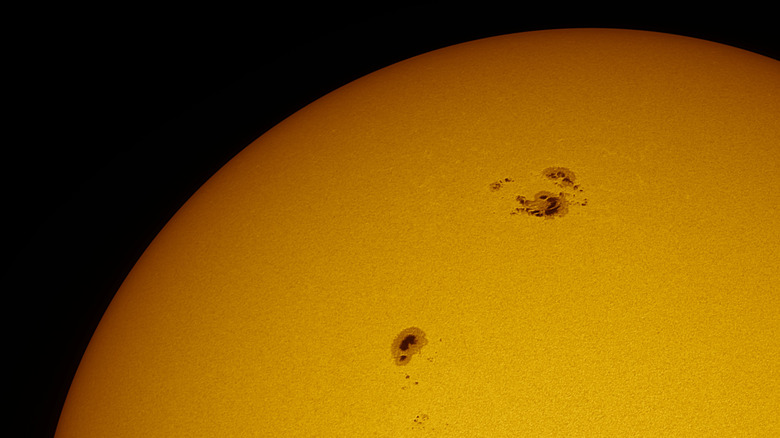

Sunspots (pictured above) can mean trouble. These darker regions are cooler than their surroundings, but are often signs of warped magnetic fields in the sun's corona bulging with superheated plasma. Our star eventually vomits massive amounts of this plasma when those magnetic fields break. Solar flares happen when plasma is shoved back into the face of the sun. It only takes the form of a coronal mass ejection when it is released into space. As NASA also observes, CMEs can send billions of tons of plasma careening through space at millions of miles an hour. This plasma can still take days to make it to Earth.

It went far beyond New York

While New York (both the city and state) was hit especially hard, the tentacles of this powerful storm stretched across the planet.

Telegraphs and phone lines began to glitch because of geomagnetically induced currents, or GICs. NASA explains GICs as being the result of plasma from coronal mass ejections (pictured above) interfering with, and actually shaking, Earth's magnetic field, which then becomes unstable. This instability means that the constant change in magnetic fields creates electric currents that can be highly disruptive to electrical infrastructures. This was felt from the US to Europe and even Japan and Australia, and it was late on the night of May 13, 1921, when the first reports of telegraph glitches came from Norway, according to Space Weather. The UK and Ireland were next.

It wasn't long before the US and Sweden began experiencing outages. In Sweden, currents got in the way of nearly every attempt to make a phone call or send a telegraph message. Denmark was not much better off, and Germany realized what was happening when an aurora blazed in the sky. Things only worsened after the morning of May 14 dawned. On the other side of the planet, Samoa and Hawaii were being struck early in the morning. Magnetometer measurements from the time have given what are still considered to be mostly accurate readings of the intensity of the storm.

Eerie lights in the sky outshone the moon

With geomagnetic storms come auroras. It is this interference of solar plasma with Earth's magnetic field that switches on mesmerizing light shows, but these were brighter than usual.

Something strange appeared to New York astronomer Latimer J. Wilson on May 14,1921, according to the New York Almanack. A sight in the sky struck him as out of the ordinary. It started out like a wispy cloud of moonlight creating something of a halo around the star Arcturus. The cloud grew larger and morphed into unearthly colors from emerald to amethyst, ever-changing displays that vanished almost as soon as they materialized. Crowds paused to stare at the light show above. At their strongest, the strange lights were brighter than the moon.

It wasn't just the moon that temporarily lost its spotlight. As the Solar-Terrestrial Center of Excellence reports, the aurora grew bright enough for some stars to end up barely visible, and it illuminated the night with enough light to read by. New Yorkers were also not the only ones taken aback by the scene. Far away from the City that Never Sleeps, parts of the West Coast and the Southwest, including Arizona, California, and Texas, were also lit up, and images of the phenomenon were captured in black and white at Arizona's Lowell Observatory, as seen in a 1921 submission by astronomer O.H. Truman to Popular Astronomy magazine.

Railroads and train stations caught fire

While the aurora caused by the gargantuan coronal mass ejection was a sight to behold, its consequences went beyond vast rainbows of light.

The currents brought on by geomagnetic storms often interfere with electrical infrastructure. While the aurora continued to dazzle from above, telegraph and phone operators were running into problems, and the journal Space Weather highlights the most severe fires caused by the storm. In Brewster, New York, one switchboard operator at the local train station suddenly realized flames were spewing from his switchboard, and he rushed to evacuate the building. He noticed someone sleeping in the station and managed to wake him before there was a fatality. Everything there was soon engulfed by tongues of fire. Yet another fire sprang up near New York's Grand Central Terminal (pictured above circa 1920), and another seemed to burst out of nowhere from a phone system in Karlstad, Sweden.

Railroads in the New York area were in the greatest danger, susceptible to being ravaged by the storm because of their position, and the Union railroad in Albany was one of them. According to researchers Love et al. who published a 2019 study in Space Weather, the Union Railroad Station went up in flames after its telephone lines were ignited by a barrage of currents. The destruction in New York City and the state of New York is what gave this geomagnetic storm its name: the New York Railroad Superstorm.

Telegraph lines and railroad systems were seriously affected

Fire might have been the most dangerous consequence of the storm, but many phone and telegraph lines that escaped being fried by the currents still went down.

As the May 15, 1921, issue of The New York Times reports (via Space Weather), currents were erratic. Telegraphs and landlines were especially affected. The East Coast saw the most destruction. It was especially New York that suffered the failure of telegraph systems that were necessary for railroad communications. Train systems relied on some of these telegraph lines for support. Almost all wires were dead from overheating — even underground wires, which the current was strong enough to reach. Fuses and other parts of the infrastructure were busted by electric currents as wire voltages went out of control.

Some voltages shot up to 1,000 volts. To give an idea of just how high that is, the Energy Recovery Council warns that anyone exposed to voltages over 1,000 risks serious burns, which can be insidious because the severity of the damage might not be apparent for days. Electrical shock at that level may not be fatal but has its own dangers. Among the many risks of electrical burns that are left undetected and untreated are chronic muscle pain, fatigue, and even the eventual amputation of limbs with too much tissue damage to function.

Radio signals were surprisingly amplified

With telegraphs and phones going down, it seemed that much of the planet was left with no way of communicating — but the storm had a surprising side effect.

Higher conductivity was actually better for radio signal strength, as researcher Mike Hapgood states in his Space Weather study, especially because radio systems in the 1920s were very low-frequency. What does frequency have to do with it? The frequency of radio waves and other types of radiation refers to vibrations per second. Earth's surface conducts electricity (or else underground telegraph lines wouldn't have died). With a frequency that was low enough, radio signals could use that conductivity to their advantage without breaking down, and they were boosted wherever there was higher conductivity. This explains how some radio communications were able to spread and travel to their destinations even when telegraphs and phones were down.

There was still a downside to radio communications when the atmosphere was being invaded by particles of solar plasma, because radio signals also travel far above the surface. There was sometimes interference between some of the that were being zapped through the sky and the ground. That aside, according to defense contractor Arcfield Weather, radio signals made it to New York from Berlin, Germany, and Bordeaux, France. Radio broadcasts from Europe also reached the US. It wasn't limited to that, since signals were also going back and forth between Samoa and New Zealand.

What happened in space was just as extreme as what happened on Earth

If the fires and outages that plagued Earth were disastrous, how the storm emerged and rocketed through space was even more extreme.

Astronomers at Mount Wilson Observatory had been trying to make out what was going on right before the storm began and as it raged. According to original observation data re-analyzed by researchers Lundstedt et al. in a study published in Annales Geophysicae, it is thought that the far side of the sun, which faces away from Earth (and was difficult, if not impossible, to observe with a telescope in 1921) gave birth to a disturbance that would eventually grow into a massive solar storm. The research team hypothesizes that this disturbance spawned on the far side because it had already become something of a monster by the time it was observable at the sun's extreme east end. It would soon creep to a more visible region on the Earth-facing side before finally exploding toward our planet.

Another study by Silverman et al., published in the Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, focuses on what happened when plasma hit Earth's magnetosphere and auroras flashed in the darkness. What is considered a rare phenomenon is that auroras happened even at low latitudes — right above and around the equator. Apparently, this storm was really pushing the limits of how far its atmospheric effects could go.

Even Einstein's theory of general relativity was challenged by it

Who would doubt Einstein? Back when his theory of general relativity was fairly new, some other scientists did, and one actually tried using the auroras in the sky to prove him wrong.

What even is relativity? The once-controversial theory is based on gravity, as NBC Mach states. Einstein went beyond assuming that the force of gravity just drew one less-massive object to one that was more massive. Instead, he proposed that gravity actually warped space, and the more mass an object had, the greater its warp effect. The reason the planets in our solar system orbit the sun is because it shapes the space around it in a way that keeps them in their orbits. That was going to cause some problems when he arrived in New York City to lecture around the time of the 1921 storm.

Before Einstein came up with general relativity, physicists believed in something known as the ether (not to be confused with the sedative), according to the New York Almanack. This was supposed to be the invisible, intangible stuff of the universe. Everything was supposedly floating in the ether. Einstein's theory, which not only did away with the ether but relied on its absence for gravity to have an effect on space, was shocking to a professor who was convinced that the auroras overhead were evidence of the ether.

It might have been as intense as the infamous Carrington Event of 1859

Could the 1921 storm have wielded enough power to match or even surpass what is believed to be the most devastating solar storm of all time — the Carrington Event of 1859?

The sky appeared to have gone up in flames from blood-red auroras, which sparked rumors of massive fires in the distance and even an impending apocalypse, according to History. Light from these auroras was so brilliant that people and animals were suddenly waking up in the middle of the night thinking it was already morning. The air was so charged it seemed as if everything was flammable. Circuits broke out in fiery sparks, and the paper that telegraph operators were using to record messages caught fire.

The problem is that there is not enough data to prove which storm was stronger, as Love et al. argue in a study published in Space Weather. Less advanced astronomical equipment could have contributed to the 1921 storm being underestimated for decades before the data was reviewed again. Exactly how strong the Carrington Event was may never be known, because while there is a range of intensity, it cannot be narrowed down as much as that of the 1921 storm, which is not exact but much more accurate. The result Love and his colleagues got falls somewhere in the middle of the Carrington range, so there is a possibility of Carrington being dethroned. There is just no way to confirm it.

If would be much more destructive if it happened now

The New York Railroad Storm caused enough destruction over 100 years ago. Because we have much more advanced technology now, a storm of this magnitude would do even more damage.

In their scale for geomagnetic storm levels, NOAA describes the unnerving consequences of a hypothetical extreme storm. Phone and telegraph lines were mostly at stake in 1921. Fast-forward more than a century, and we are much more dependent on electricity and power systems. Almost nothing that needs to be plugged in would work, and voltage would spiral out of control, with entire areas experiencing blackouts for days (if not longer). Satellites and other spacecraft would also get hit hard. Plasma would overcharge them, they would be thrown off their orbits. Even if computers were still functioning on Earth, it would be difficult to track a satellite losing its way..

Satellites wouldn't be the only victims. NOAA also remembers a particularly scary solar storm that gobsmacked Earth several days before Halloween in 2003, and while it was nothing like 1921, it is remembered as one of the most intense in the past few decades. This event was caused by double coronal mass ejections that triggered two geomagnetic storms in rapid succession. It scorched an instrument on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter and forced astronauts on the International Space Station to take cover from dangerous radiation. Back on Earth, air travel was disrupted, communications failed, and GPS systems malfunctioned.