What An American Presidential Funeral Is Really Like

Pomp and circumstance on state occasions is something America has an uneasy relationship with. Per the Pew Research Center circa 2017, Americans aren't shy about their national pride, and from the State of the Union address to presidential inaugurations, the United States employs formal ceremonial trappings on major national occasions. But there's a leeriness in America towards certain displays of pageantry common elsewhere. Among President Donald Trump's many controversies was his desire for the sort of military parade he saw in Europe, which was strongly opposed by army brass (per Business Insider).

But military and government actors do come together for one piece of statecraft: the presidential funeral. Initially developed for sitting presidents and modeled after the rites used for monarchs in the Old World (per The White House Historical Association), it evolved over 180 years into the modern ceremony of mourning and tribute to departed heads of state. The time dedicated to the funeral is typically five days, though it has varied from president to president. An official page by the U.S. Army once described an American state funeral as a blend of military protocol, national tradition, and the personalized wishes of the president being honored or their family; the nature of each blend affects the length and composition of the ceremony. With that being said, here is what an American presidential funeral is really like.

State funerals aren't just for presidents

The U.S. Army lists former presidents, sitting presidents who died in office, and presidents-elect who died before taking office as those eligible to be honored with a state funeral. As the head of state, the U.S. president serves as an embodiment of America during their time in the White House, and each one's passing marks the end of a particular period in history, per Britannica. But besides getting the honor themselves, sitting presidents also have the discretion to award a state funeral to someone else.

Anyone that a president would like to have a state funeral could technically get one, though they will have needed to achieve significant prominence on the national stage. Part of a state funeral is — well, lying in state, in a state building open to the public, and the Architect of the Capitol maintains a list of those so honored. The first non-president on the list is Henry Clay, the noted statesman of the 1800s. Others who have lied in state include congressman Thaddeus Stevens, General Douglas MacArthur, and the unknown soldier of the Vietnam War.

One more recent non-presidential state funeral was for Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020, who died during her tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court. Per The Times of Israel, she was the first woman and the first Jewish person to receive such honors.

A state funeral is optional

A presidential funeral is intended as an honor, both to the office and the officeholder being put to rest. They also function as what The White House Historical Association describes as the nation's last connection with the departed president. But it isn't an honor or a conversation that presidents or former presidents are obligated to undertake. Presidents can and have opted to forego elements of a traditional state funeral, and in some cases, to do without one altogether.

Gerald Ford, according to The White House Historical Association, needed convincing as to the importance of some traditions, and modified several of the ones he retained. He augmented his lying in state by having his body rest in both chambers of Congress (he had served in the House and the Senate before becoming president) and relented on his desired motorcade through Alexandria, Virginia, for the more traditional carriage trek down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Richard Nixon went further in departing from the standard ceremony. His funeral was held in the Nixon Library in California, rather than Washington, D.C. It couldn't be described as low-key; per Politico, Reverend Billy Graham officiated, then-president Bill Clinton delivered one of the five eulogies, and four other former presidents attended along with Clinton. But it was, by his own wish, completely removed from the nation's capital.

They weren't the norm in the country's beginnings

The presidential funeral as a formal occasion of state is a relatively recent development for America. At the nation's founding, there was no set protocol for the government to mark the passing of noted figures, let alone presidents. When George Washington died, according to NPR, he was buried at his home, Mount Vernon, in a private ceremony. Not that Washington's death went unmarked by the United States; the Papers of George Washington exhibit at the University of Virginia notes that Washington's family involved his Masonic lodge in preparing rather elaborate trappings for a private funeral, and Mount Vernon details the honors and tributes paid to Washington away from his home.

The tradition of private funerals at home endured after Washington for some time. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who both died on July 4, 1826, followed Washington's lead, though their funerals had very different characters. According to David McCullough's "John Adams," though Adams asked for a simple service and his family declined funding from the state of Massachusetts, his passing was marked by bells, cannons, and 4,000 mourners, while Jefferson's family sent out no invitations to his funeral. While crowds gathered to see the internment, the service itself was conducted by a small group of relatives and friends, per Monticello.

State funerals began with William Henry Harrison

America didn't see a president pass away in office until William Henry Harrison in 1841. President for only a month, the shortest tenure in history, Harrison was still head of state when he died, per The White House, and according to The White House Historical Association, it was felt that a public show of mourning was due to the office. Arrangements were handled by a pair of merchants, Alexander Hunter and Darius Clagett (per The White House Historical Association). The service itself was a relatively small affair, attended by invitation in the East Room of the White House. But the mansion's interior was shrouded in black, and 30 days of tributes followed before Harrison's body returned to his home state of Ohio.

While lacking many elements of the modern ceremony, Harrison's did set the precedent for a state funeral in honor of a president. His was the example followed when Zachary Taylor died in office in 1850. Taylor's funeral saw an early example of personal touches added to the ceremonies; a noted military figure before becoming commander-in-chief, Taylor had a horse known by name, Old Whitey. Per The White House Historical Association, Old Whitey followed his master's coffin with an empty saddle.

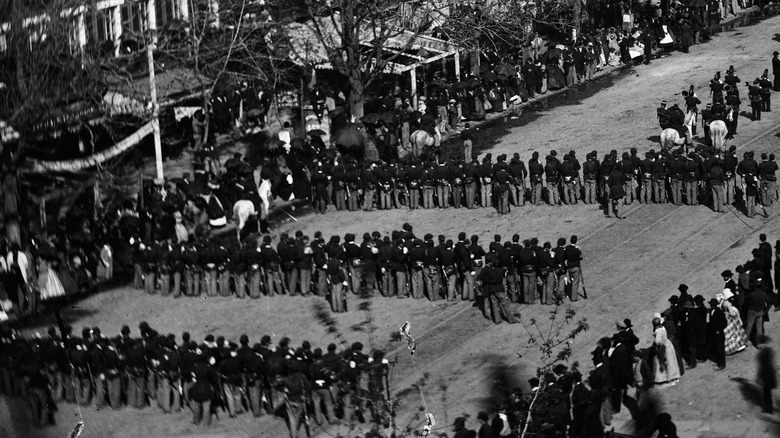

Abraham Lincoln's funeral set a precedent for scale

A public show of mourning in Washington, D.C. for a president who died while in office began in the mid-1800s, as described by The White House Historical Association, but it was with Abraham Lincoln that presidential funerals became national events by modern standards (per NPR). Lincoln's assassination after the Civil War was a devastating blow for the United States, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton determined that the country would have a chance to say their farewells.

Over the initial wishes of Lincoln's wife, Mary Todd Lincoln (who proved too grief-stricken to attend any tributes), Stanton planned an elaborate route for Lincoln's body to take through America, reversing the president's journey to Washington ahead of his inauguration (per History). After two days of lying in state at the Capitol, Lincoln's body was loaded onto the presidential railroad car, bound for Springfield, Illinois, with stops at every major city along the way. In 10 of the cities, Lincoln's body was put on public display, and after reaching Springfield, it spent several years moving around resting places. "It's a ballpark of about 15 times that his coffin was moved," author Louis Picone told NPR.

For an idea of the scale of mourning that marked Lincoln's death, consider the numbers presented by the National Museum of American History. Lincoln was killed on April 15, 1865; by April 19, around 25 million Americans across the country took part in memorial services, 120,000 in New York alone.

The scale of ceremony has receded with time

The first state funeral for a president, held for William Henry Harrison, took its cues from the royal funerals of Europe. That level of grandeur was aspired to for some time afterwards, per The White House Historical Association. Black drapes adorned the White House, horses drew a handsomely dressed carriage bearing the coffin, and fleets of dignitaries walked in processions filled with salutes. For one of the grandest of all, that of Abraham Lincoln, the journey from Washington, D.C. to the president's home state involved public viewings of the body in major cities along the way.

With the assassination of William McKinley in 1901, the first president of the 20th century to die in office, the character of the presidential funeral began to shift. The body still lay in state in the Capitol, and there was still a large procession to see it off to Ohio, according to The White House Historical Association. But the decorations in the White House were floral, and considerably scaled back from past presidential funerals.

Further simplification followed with the funerals of Warren G. Harding and Franklin D. Roosevelt, and these somber but comparatively modest examples have guided the modern ceremony. The White House Historical Association suggests that these changes were part of a broader move away from pomp in the 20th century.

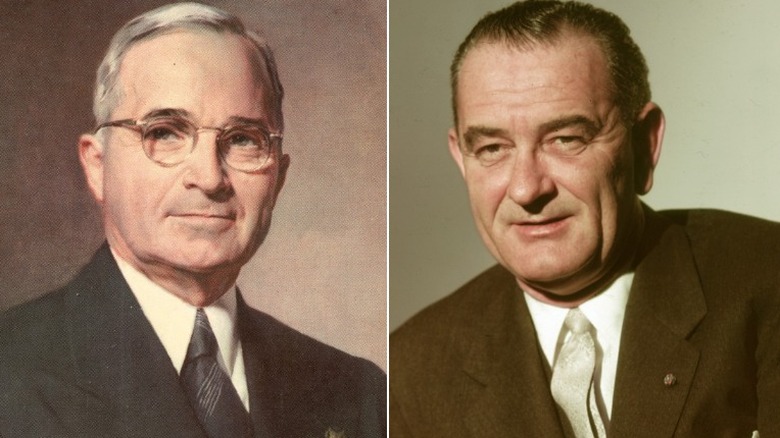

Two presidents had funerals a month apart

The United States saw a study in contrast when two presidential funerals were held within a month of one another. In December 1972, Harry S. Truman died at 88, per Britannica. He had, according to The New York Times, approved plans for a five-day state funeral, but after his death, his widow amended the arrangements in favor of a two-day private ceremony held at the Truman Memorial Library in Independence, Missouri. Elements that had become standard in presidential funerals, including a horse with an empty saddle and an elaborate military procession, were replaced with 20 cars.

After the new year, Lyndon B Johnson passed away, and there was a two-day overlap between the public mourning periods for Truman and Johnson, according to The White House Historical Association. The latter opted for a more traditional state funeral. His body was flown from Texas to Washington to lie in state at the Capitol, with the arrival marked by a flyover by air force planes. The service was held on January 25. Among the elements retained by Johnson that Truman had done without was the horse-drawn carriage bearing his coffin. After his passing was observed in the nation's capital, Johnson's body returned to Texas for final burial.

Presidents help plan their own funerals

Among the many heavy responsibilities that come with the keys to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is the need to plan your own funeral. According to The White House Historical Association, one of the first things incoming presidents are asked to do is weigh in on what services and ceremonies they would like included or excluded in the event of their death, so that the Military District of Washington can have a plan of action ready to go. Besides allowing the chain of command to be ready in the event of an emergency, this arrangement lets a president personalize their final departure from American public life.

Sometimes, these plans can come to light before a president is laid to rest. In 2006, Jimmy Carter — still very much alive — shared a small example of his funeral arrangements with Deseret News. Carter said that, after a service in Washington, he would like his final resting place to be his hometown of Plains, Georgia.

They are held in three stages

The modern presidential funeral, as described in documents prepared by the U.S. Army, is a three-step process. Assuming other arrangements haven't been made at the president's request, the first stage sees honors paid to the deceased in the state where they lived at the time of death. The remains of the president might be placed in their presidential library, or in a local site like a museum, for public viewing, and a service might be held at a local church. Ceremonies might also be held to mark the president's remains leaving from where they initially lay, and when they leave for Washington, D.C.

The second stage is held in Washington and sees the president lie in state in the Capitol building. Leading up to that is an arrival ceremony at Andrews Air Force Base and a procession down Constitution Avenue. If another location hasn't been specified, the remains are taken to the Washington National Cathedral after lying in state for a service, and another round of departure ceremonies see the president off to their final resting place.

In the third stage, the president is interred with one last service or ceremony. Various branches of the military are designated as having a role to play in laying a president to rest, but their actual service in the funeral is determined by the wishes of the president and their family.

The Washington National Cathedral has played a big role

A prominent location of modern presidential funerals has been the Washington National Cathedral. The church's official website states: "Washington National Cathedral has been the location of funeral and memorial services for nearly all U.S. presidents since ... 1893." That distinction between funeral and memorial services is important; only four presidents have had funeral services conducted there, and only one — Woodrow Wilson — is buried in the cathedral. But memorial services have been held there since the death of Warren G Harding in 1923.

The four presidents to have funeral services hosted by the cathedral are Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush. Besides Harding, four other presidents have been honored with memorial services — William Howard Taft, Calvin Coolidge, Harry S Truman, and Richard Nixon. The Episcopal bishop of Washington, whose seat the cathedral is (per the Library of Congress), also provided an address to mark William McKinley's death and officiated the White House funeral service of Franklin D. Roosevelt. To mark the death of the Catholic John F Kennedy, the cathedral was open overnight to allow mourners space to pray.

The cathedral also has the distinction of hosting the funeral of Edith Wilson, Woodrow Wilson's wife, and she is the only first lady to have had a service there. The ceremony was conducted by her grandson, Francis Sayre Jr. President Wilson was initially buried in the Bethlehem Chapel, but he was later interred with his wife in the Wilson Bay, per the Washington National Cathedral's website.

Why do they get a 21-gun salute?

One aspect of the presidential funeral is shared by ceremonies throughout the world: the 21-gun salute. This long-used symbol of respect is brought out on many occasions; Arlington National Cemetery lists the 4th of July, President's Day, Memorial Day, and George Washington's birthday as days to fire the guns, along with visits by foreign heads of state and presidents, sitting and former. The salute is also sounded at noon during presidential funerals.

The U.S. Army Center of Military History traces the origins of the 21-gun salute to an ancient custom of signaling peace by rendering weapons harmless, a practice that predates gunpowder and seems to have been observed worldwide. As cannons became prevalent in the 14th century, warships would fire their single-shot guns to show they meant no harm, and fortifications at harbors would do the same. The number 21 derives from the original 7-gun salute used by the earliest cannon-bearing warships, which itself appears to stem from symbology linked to the Bible and astrology.

The firing of 21 guns was the traditional salute among European powers by the 19th century. In the United States, the number of guns used to honor a president was initially tied to the number of states currently in the union. While the U.S. adopted the 21 number for presidential salutes by 1842, it didn't commit to the same for international honors until 1875, or to non-presidential domestic occasions until 1890.

They're initiated by a sitting president

How does a state funeral get underway? As with any funeral, it begins with death. Traditionally, according to a guide published by the U.S. Army, the family of the deceased president will use their office or press connections to issue a public statement on their passing. But while presidents are invited to have a hand in planning their funerals while they're alive, their death does not automatically trigger preparations for official state services and ceremonies. To commence a presidential state funeral takes a president — a living president.

After receiving word of the death of their predecessor, the sitting president is responsible for formally proclaiming it to the nation at large. Unless a state funeral has been declined, the sitting president must also authorize the Department of Defense to begin putting it together. The Joint Task Force-National Capital Region, the military element also responsible for presidential inaugurations (per the Joint Task Force-National Capital Region website), handles the operation.

They're paired with a national day of mourning

With various services and ceremonies, spread over three stages in multiple states and cities, a presidential funeral can be a lengthy affair; The White House Historical Association gives five days as the traditional number. But among a sitting president's obligations to their predecessor is the designation of a national day of mourning, a specific date marked by the closure of non-essential government services, and a show of tributes to the deceased (per USA Today).

The date of a national day of mourning for a former president is traditionally the same day that funeral services are held in Washington, D.C., a practice dating to Franklin D. Roosevelt's death, according to a guide published by the U.S. Army. In the event no service is held in the capital, the day of mourning is designated for the date that the president is interred in their final resting place. As of late 2022, the most recent presidential day of mourning (per the Joint Task Force-National Capital Region) was December 5, 2018, for George H.W. Bush; the first was Franklin D. Roosevelt's, on April 14, 1945.