What British Royal Family Visits To Other Countries Are Really Like

Queen Elizabeth II was known for many things — her longevity, her tact, her hats, her corgis. She was also known for her breadth of travel. In the wake of her death, the Telegraph counted 117 countries visited for 290 separate state visits. She undertook more royal tours beyond the shores of Britain than any previous monarch, and her overseas trips offered popular fodder for the press at home and abroad.

The queen wasn't the only member of her family to undertake royal visits, and the practice seems unlikely to disappear after her death. The Mirror claimed that King Charles is planning a two-year program of overseas trips, primarily among Commonwealth nations, ahead of his 2023 coronation. But any future plans are likely to be complicated by the decidedly cool reception that the 2022 trip to the Caribbean by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge received (per the CBC). Skepticism has already been turned on the concept of the royal tour by media outlets under monarchs and presidents alike (see CNN for an example of the latter). And even in the best of times, a royal visit is no idle lark; they take a lot of work.

They go back a long way

There were no cameras in the medieval, classical, or Bronze age worlds. There were no 24-hour news networks, no trending topics on social media, and no tabloids. But royal tours have been a component of the monarchy since the institution's inception. As Stephen Bates of The Guardian has noted, in an era where kings and queens wielded considerable governmental power as well as symbolic influence, they needed to demonstrate their authority, their majesty, and their continued suspiration to their subjects.

Royal progresses were a regular occurrence within the realms of medieval kings, which sometimes took English monarchs from Albion's shores. Bates claims that Henry II's extensive travels across the Angevin Empire left him bowlegged. Later centuries saw royal visits to far-off colonial outposts; the Department of Canadian Heritage records a tour made by the future William IV in 1786.

Diplomatic visits by royals to lands beyond their rule also predate the modern era. The official website of Mount Vernon lists prominent visits by the British royal family to the United States since 1860, when the future Edward VII came to George Washington's historic home.

They're in a symbiotic relationship with the press

Relations between the British royal family and the media are often ambivalent and sometimes mutually hostile. Yet the monarchy, as Queen Elizabeth II herself once said, must be seen to be believed, and the press is the agent by which the royals reach most of their subjects and the greater world stage. No state visit or official royal tour can be carried out without a small fleet of British, local, and international press in tow.

Stephen Bates discussed the symbiotic nature of the media's presence on royal tours in The Guardian. The monarchy needs the publicity, even the often-dismissive publicity from non-British journalists and republican reporters from home. Besides supporting their position, the coverage brings attention to causes they champion. But the press gets something out of the royal tours too: a subject. For all the costs and long hours accumulated by such trips, media organs know that they can sometimes offer up splashy headlines, eye-catching copy, and a slightly more intimate look at what Britain's ceremonial head of state and their family are really like.

They can take up to a year to plan

As the head of state of a major nation, the British monarch can't just pop off anywhere, and nor can their family or representatives. Even a private holiday needs some arrangements for security, and any official state visit overseas requires meticulous scheduling, choreography, and international coordination. The responsibility for seeing that such visits go off without a hitch is split between British and host nations.

For an example of the responsibilities of the latter, consider the Globe and Mail's interview with Kevin MacLeod, who was Canada's Usher of the Black Rod when the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge visited Canada in 2011. He said that the average royal tour involved up to a year of preparation on his office's end (that year's visit by William and Kate got three months). The amount of prep time and the length of the visit helps to dictate the itinerary. Other factors include the need to offer a variety of events for the press, the wishes of states or provinces in the country, and whether or not a certain location or event has already seen a royal visitor in recent memory.

Royals are required to travel with mourning clothes

Even a short trip overseas requires a suit or two of spare clothes. The British royal family never travels without wardrobe options. But with every international tour and state visit comes a rather grim obligation: to have a black outfit ready. The reason, according to royal historian Jessica Storoschuk (via Page Six Style) is that, in the event of a death in the family, the royal abroad can cut their trip short and re-enter Britain already dressed in mourning clothes.

This requirement of royal protocol caused a minor issue when the then-princess Elizabeth went on a royal tour of Kenya in 1952. Her father, George VI, was in poor health and passed away during her trip. But the princess, now Queen Elizabeth II, had no mourning dress. When she returned to the U.K., she had to wait aboard her plane until black clothes were delivered to her before she disembarked to receive condolences from Winston Churchill and other government figures.

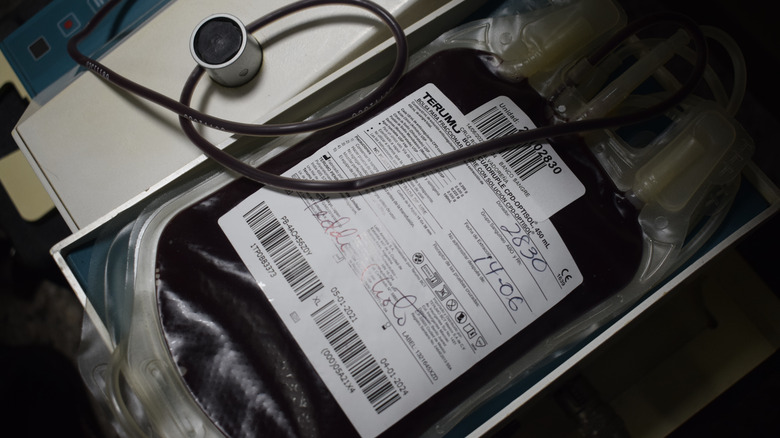

Doctors (and blood) travel with them

Constitutional monarchs may no longer directly command legions of knights, but they don't lack for security. Royal visits around the world see them well-attended. It's not just protection from potential harm by hostile actors that's accounted for either. Per Yahoo! News, the working royals in direct line for the British throne (Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Charles, and Prince William at the time the article was written) travel with a royal physician as well as their working entourage of 12 to 14 staffers.

Of course, even the best doctor in the world can't do much in the event of an accident or injury if they lack necessary supplies. Some state visits can put the royals in places where reaching a hospital with, say, a ready supply of blood for transfusions is unfeasible. So, as an extra precaution, another thing the front-line royals always travel with is a bag filled with their own blood.

Royals are expected to know at least some of other languages

The British monarchy plays an important diplomatic role for the country. On many of those royal visits, they act on behalf of the monarch, if it isn't the monarch undertaking the tour, in their capacity as Britain's head of state. This sometimes takes them outside the Anglosphere. Even within Britain and the Commonwealth, languages besides English are spoken. It would be unrealistic to expect that the British royal family be fluent in every tongue they come across. But it is expected of them, etiquette teacher Myka Meier told Reader's Digest, that they be briefed on local greetings so that they can show proper respect to their hosts.

Not that the royals aren't without skill at other languages. According to Euronews, King Charles is fluent in French, and Queen Elizabeth II was nearly so. She also knew Doric, a Scots dialect native to the region around her Balmoral estate. The king is knowledgeable in German and Greek, and he and Prince William have some knowledge of Welsh. The newest generation of royals is reported to have picked up Spanish; William's children have learned some of the language from their nanny.

Visits to any one place are short

Reporter Gordon Rayner spent 20 years accompanying the British royal family on overseas visits, and he offered his recollections to the paper that sent him, the Telegraph, in 2016. He expressed awe at some royal visits, most notably Queen Elizabeth II's 2011 tour of Ireland, and took a more sardonic attitude toward others. And he offered up a rather frank comment about what such diplomatic work entails. "Touring the world meeting heads of state and being shown cultural treasures sounds like a wonderful life," he wrote, "Yet I have no envy for the royal family."

An overseas state visit is a diplomatic mission, not a vacation. Whichever royal undertakes a given tour, their schedules are meticulously timed and enforced. Rayner estimated that their average time at some of the world's most notable places came in at around 40 minutes. It isn't as though the royals can enjoy such sites while they're there either, because they have local dignitaries they need to talk to, photo-ops they need to participate in, and a press tail they need to mind. And odds are that some of the places they are so hurriedly walked through, they'll never get a chance to revisit at a more leisurely pace.

The dress code is strict

Being carefully manicured pieces of statecraft, state visits by the British royal family can't be conducted with just any old thing out of the closet. Outfits must be many and varied, and they're the subject of considerable forethought. Reporter Gordon Rayner told Telegraph readers that Angela Kelly, senior dresser to Queen Elizabeth II, would travel ahead of her sovereign to any tour destination to conduct due diligence for the wardrobe. Considerations included local customs and sensibilities, color choices, head and footwear protocol, and how a given dress might look against a certain vista. The prep work could be done months ahead of time, and the queen could travel with up to 30 outfits on any one trip.

Royal couture is catnip for fashion magazines, particularly that of the younger royals. When Meghan Markle was still a working member of the family and undertook her first engagement in Ireland, Vanity Fair published a collection of photos showcasing her outfits and passing on suggestions for royal footwear based on previous tours undertaken by the Duchess of Cambridge. This kind of coverage has no direct comment to offer on the diplomatic or charitable nature of many royal engagements, but it does help raise their profile.

A few luxury items get brought along

Most of us like to have a few creature comforts while traveling. However exciting new sights, tastes, and sensations abroad can be, one or two items from home can ease any burdens from the trip. In the case of the British royal family, the comforts of home that travel with them sometimes include booze. Queen Elizabeth II enjoyed a 50/50 mix of Dubonnet and gin, according to the Telegraph, while King Charles favors a gin and tonic. This isn't entirely a matter of luxury; there is a chance, however remote, that the monarch could be slipped a spiked drink if it comes from outside their control.

If pre-packaged alcohol has at least some security value, the king bringing his preferred brand of honey, or an artist to paint the scenery, can seem like mere extravagance. Charles has justified the latter practice as a way to support up-and-coming artists. And he isn't the only member of his family to indulge a sentimental side while undertaking royal tours. The queen tried to get her corgis into her entourage whenever possible (per the Telegraph).

The costs are split

Official visits by the British royal family to another nation are, by nature, visits of a head of state (or their representatives) of one country to another. It seems natural that the costs of such visits should be divided. The British end includes travel expenses. Sky News reported that the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge's visit to the Caribbean in early 2022 cost British taxpayers £226,383 for their flight, and then-Prince Charles' trip to Barbados in December 2021 cost £138,457. This money would come out of the Sovereign Grant, an annual lump sum paid by the government to the reigning monarch to fund official duties.

While the U.K. often pays to send the royals out and bring them back, the host nation takes on the majority of the cost for a given tour's itinerary — the local travel, the photo-ops, the ceremonies, and official functions. When Queen Elizabeth II visited Australia in 2006, her five-day trip cost her Australian subjects A$1.8 million according to a Senate report (via the New York Times). A more recent visit, by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge to Canada in 2016, was estimated by the British Columbian government to cost the province $613,363.93 (via the CBC). The same trip involved $2 million in security costs and over $41,000 in accommodation. It was also a case of the host nation paying the travel costs from and to Great Britain: $45,205.64.

Anti-monarchy protests are common

The monarchy remains broadly popular in the United Kingdom, and 14 other nations still retain the British sovereign as their head of state (per the Council on Foreign Relations). The level of support for the institution, and the relationship of some of these nations with Great Britain, has changed considerably since the dissolution of the British Empire, and some countries are trending towards cutting ties with the monarchy in favor of native heads of state. Besides opposition to the monarchy as a concept, some protestors have also targeted it as a symbol of perceived lingering injustices, as the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge found in their controversial tour of the Caribbean in 2022 (via CNN).

CNN reporters were careful to note that the royal family's public position on republican sentiments is that it's a matter of self-determination for each of the Commonwealth realms. And while protests against the monarchy picked up significant press coverage during the Caribbean tour, they're nothing new for royal visits. Separatists in Quebec targeted Prince William's 2011 visit to the province (via the Guardian). And in 1868, while visiting Australia, Prince Alfred was the target of that country's first assassination attempt according to the National Museum Australia.

Royals aren't supposed to travel together (but they do)

Lines of succession to a state position are important to ensure a smooth transition of power and responsibility. Disruptions to the succession can complicate and even jeopardize such transitions. So it's understandable that policies and norms would be in place to protect a successor when the current occupant of a position faces any elevated risk. Flights are a potential risk, so an unwritten policy among the British royal family (per Cosmopolitan) is that those in direct line for the throne don't fly together.

It's a policy that hasn't been rigidly enforced, though. The reigning sovereign has final say over breaks with the protocol, but exceptions have often been forthcoming as air travel's safety has increased over the years. The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge were granted an exception by Queen Elizabeth II to bring all three of their children with them on the same flight up to Balmoral in 2019. Before that, they were allowed to bring Prince George with them to Australasia in 2014.

They can't say whatever they please

During the protests that dogged the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge's tour of the Caribbean in 2022, controversies about the impact of colonization, slavery, and imperialism were put front and center. Demonstrators, activists, and commentators called the images of the British royal family visiting former colonies "problematic" and dismissed their contributions to the conversation about historical injustices. "I don't understand what the purpose is of them," activist Naomi Evans told CNN, "unless it's to go and apologize, and start talking about how you repair the damage."

But in many of their state visits, the royal family are acting as representatives of the British government of the day. It's part of the job of constitutional monarch; you are the head of state, pressed into diplomatic service. Any formal apology would be up to the government to make, through the royals or otherwise. William and Kate couldn't have made such a gesture unilaterally even if they wanted to.

The same is true for questions of reparations and separation from the British crown. As Stephen Bates of The Guardian writes, the royal family has long been accepting of the right to self-determination among Commonwealth nations who their head of state will be. They can't halt a move to drop the monarchy, nor can they authorize or deny any payment of reparations for past wrongs. Just who would be the recipient of certain repatriated treasures, and where they would go, isn't always straightforward either.