How The Ancient Romans Pioneered The Modern Courtroom Drama

We all know film and TV's impassioned lawyer monologue scene by now, right? Sweeping gestures in the courtroom and pleas to the jury for rationality, compassion, or wisdom; grandiose, monolithic statements about truth, justice, holding the guilty accountable, and preserving the lives of the innocent; the stunned faces of jurors, audience members, and opposing legal counsels blinded by dawning realizations unveiled by the unshakable power of oratory. The best of lawyers, our fictions seem to say, are magicians and ringleaders who — by nothing more than voice, charisma, and rhetoric — ensorcell the minds of listeners and sculpt them at will.

In the modern day, we have decades' worth of courtroom procedurals and legal dramas professing this same tale of belief in legal proceedings to rightly shape society: "Anatomy of a Murder" (1959), "To Kill a Mockingbird" (1962), "A Few Good Men" (1992), and "The Trial of the Chicago 7" (2020) to name a scant few. But, the stories imply, a society and its laws must be upheld by the few capable, willing, and talented enough to do so. Whether or not any of this self-mythologizing is true is up to the reader.

Like most things, these notions don't start and end with modernity. They go way, way back to a civilization upon which many present-day institutions derive: ancient Rome. There, as sites like Brill explain, a highly litigious society — one tailored by the persuasive power of orators — gave rise to the same courtroom spectacle that intrigues people today.

Persuasive rule in the Roman Republic

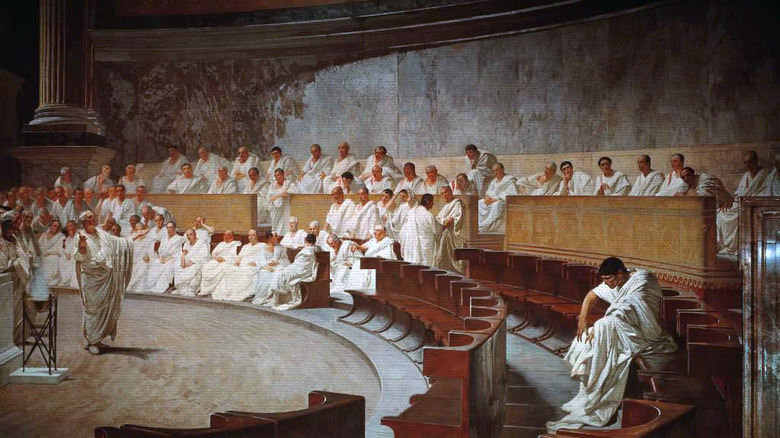

Here's a question for you: In a supposedly "democratic" society where everyone's voice equally matters, how do you know who to listen to? How do you make collective decisions if everyone's needs are different, and motivations can't be trusted? The Roman Republic (509 B.C.E. to 27 B.C.E., per Live Science) answered that question in the same way as modern, democratic states: debate, discussion, public speaking, and a consensus upheld by law. Ancient Roman elites eligible to participate in civil affairs met in the Roman Forum, a building that represented the beating heart of Rome's republic. Elections, criminal trials, speeches, business matters, religious events, and much more: all of these took place at the forum, per History.

This is why wealthy Roman households trained their children in oratory, as History Learning describes. In a society where it was necessary to wrangle one's peers to get what one wanted, rhetoric, persuasion, and skill at public speaking were absolutely critical. However, some considered this method of consensus-building a kind of moral perversion, because decisions didn't seem to be based on absolute, societally-shared moral truths. Rather, they depended on whoever could persuade — i.e., deceive — the best. As master Roman orator and advocate (lawyer) Cicero himself said, "An advocate may sometimes defend what looks like the truth, even if it is less true," as the 2017 book, "Ethics and the Orator: The Ciceronian Tradition of Political Morality," quotes on Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

Founding a new Rome

Ancient Roman values and practices are one thing, and their similarities to modern democratic processes should be obvious. But how deep does the influence go? Is it really the case that court happenings and cultural norms regarding public speaking 2,000 years ago directly impacted our modern judiciary, down to all those courtroom dramas we described earlier? In short, yes.

In the United States in particular — a wellspring of all those aforementioned romanticized visions of dramatized, moving courtroom speeches — the country's Founding Fathers very consciously modeled their newborn nation's legal structures on ancient Rome's. As Enlight Public Research Center NGO explains, the founding fathers even went so far as to identify themselves with prominent historical Romans. George Washington was the new Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a mythologized general and paragon of Roman virtues like loyalty to the state. John Adams was the new Cicero, history's greatest public speaker and lawyer. Adams even chose to go into law because of Cicero.

When these men — and others like Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson — got together to pen the U.S. Constitution and its governmental separation of powers in 1787, they knew they'd be encouraging the same risky manner of public engagement that led ancient Rome to its oratorical obsession. Democratic processes emphasize the power of voice and presentation of information over the facts themselves, just like Cicero stated. Fast forward 230 years or so, and we've got a modern-day court moved as much by facts as the swell of sentiment.

The spectacle of justice

Ultimately, practically every single facet of modern courtrooms mirrors ancient Rome: representatives for two different sides (prosecution and defense) facing off in an adversarial, back-and-forth process; the questioning of witnesses and presentation of testimonies; the use of physical evidence and related materials; a jury of peers that assesses the case and comes to a conclusion — all of it, as sites like World History Encyclopedia summarize. Not one bit of it isn't copy-pasted into modernity. Is it any wonder why the two courts, spaced apart by thousands of years, would produce the same preoccupation with verbal wizardry and dramatic engagement?

In her 2007 book, "Actors and Audience in the Roman Courtroom," author Leanna Bablitz states that the audience members were so enthralled with court proceedings that they treated cases like entertainment. They wanted to be wowed by orators and moved by pathos, much like today. Court was like a less bloody version of gladiatorial combat where verbally adroit lawyers earned as much "fame and glory" as athletes or generals. It was a deliberate spectacle, and a crucible for advocates to sharpen their oratorical skills against their fellows. Jurors may have gone into proceedings with ideals of "aequitas" (fairness, or equity) and "utilitas" (practicality, or utility) — evaluating cases of murder, theft, property damage, debt, etc., same as now — but couldn't help being swept away by rhetoric, emotionality, and skillful presentations.

Gestures of the trade

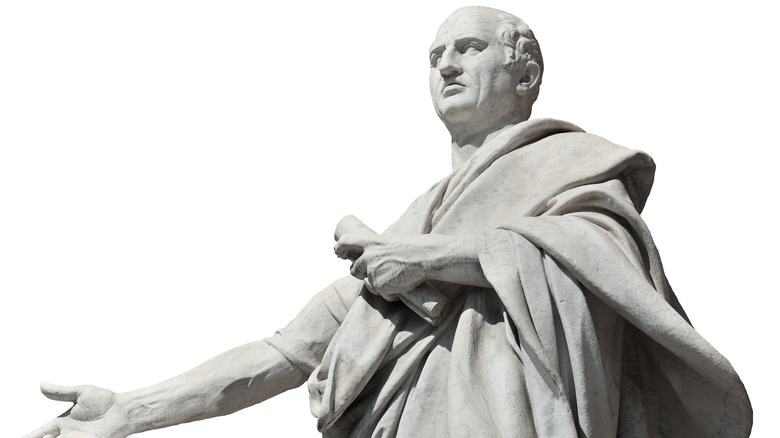

Ancient Romans were so gonzo about their courtroom entertainment, and its lawyers were so intent on beating the competition that the most renowned orators taught the use of specific body language and hand gestures to illicit emotional effects in listeners. This is especially true during Rome's imperial period after 27 B.C.E., when oratorical skills grew into greater demand, as an article in the journal The Classical Quarterly explains. Tons of Roman statues depict figures with one arm held close to the body and the other arm (always the right) extended outward. That's a clear example of persuasion in action.

In his book "Orator," Cicero laid out advice like, "The hands should not be too lively, accompanying the words with the fingers, but not imitating them." "There should be no effeminate bending of the neck," he continues, "no twiddling of the fingers, no tapping out a rhythm with the knuckle." Gestures like "striking the forehead" and "slapping the thigh" are ways of "rousing emotion in the audience," but shouldn't be distracting. The orator Quintilian gets almost absurdly specific. To portray surprise, he said, a speaker should use a gesture "in which the hand is turned slightly upwards and the fingers brought together one by one, beginning with the little finger. Then the hand is opened and turned around with a reversal of this motion." He outlined 20 precise, codified examples that speakers of all stripes — lawyers included — should employ under specific conditions.

Fame, acclaim, and notoriety

Despite all the similarities between Roman and modern court, Roman court diverges from our own in one key way. Namely, ancient Rome had no dedicated lawyers, as Michigan Law Review says. That is to say, anyone could provide legal counsel — anyone at all with ambition and a silver tongue. This is the engine that propelled Roman courts to such heights of showmanship.

For wealthy elites who didn't want to go into military service and weren't born well-to-do enough to breach higher political echelons, oratory was the pathway to "dignitas" — worth and renown in society, per The Classical Quarterly — and courtrooms the stage. Even though modern-day lawyers can rise to acclaim on their career paths, their dedicated, regimented profession curbs some of the more outlandish elements of conduct seen in Roman courtrooms.

In the end, a cleverly crafted piece of rhetoric from master orator Cicero paints Roman courtroom drama in vivid shades (via Famous Trials). As prosecutor against governor Gaius Verres, who was accused of a shocking array of theft and rape against his own constituents, Cicero's opening statement read in part, "In truth, what genius is there so powerful, what faculty of speaking, what eloquence so mighty, as to be in any particular able to defend the life of that man, convicted as it is of so many vices and crimes, and long since condemned by the inclinations and private sentiments of every one?"