The Strange Tale Of John Dee, Personal Magician To Queen Elizabeth I

Strange as it may sound, it's not too uncommon for monarchs and rulers to not only dabble in the occult, but employ personal magicians to help with decision-making. Queen Victoria, after whom the Victorian Era is named, became heavily involved with the occult following the death of her husband and love, Prince Albert. As News Punch cites, she held séance after séance for years to contact him, and kept records that advisors counseled against publishing. Way before her, famed 16th-century doctor and doomsayer Nostradamus caught the eye of the French queen, Catherine de Medici, who made him resident mystic at the court of King Henry II, per History. Much more recently, U.S. president Ronald Reagan employed astrologer Joan Quigley to schedule his meetings and trips at auspicious times, as PBS recounts.

In some of these cases, individuals like 19th-century medium Florence Cook rode a wave of public interest in spiritualism and the occult, as Victorian Web describes. In other cases, individuals like Nostradamus went against church orthodoxy at great risk to his own life — this is likely why he wrote his supposed apocalyptic visions in the form of vague poetry in 1555's "The Prophecies," as the Napoleon Series explains. But regardless of trends or prophetic truths, it's undeniable that mystics, mediums, psychics, soothsayers, and all manner of magicians have left a bigger, behind-the-scenes mark on history than many may realize. This is especially true of astronomer, mathematician, occultist, and possible spy to Queen Elizabeth I, John Dee.

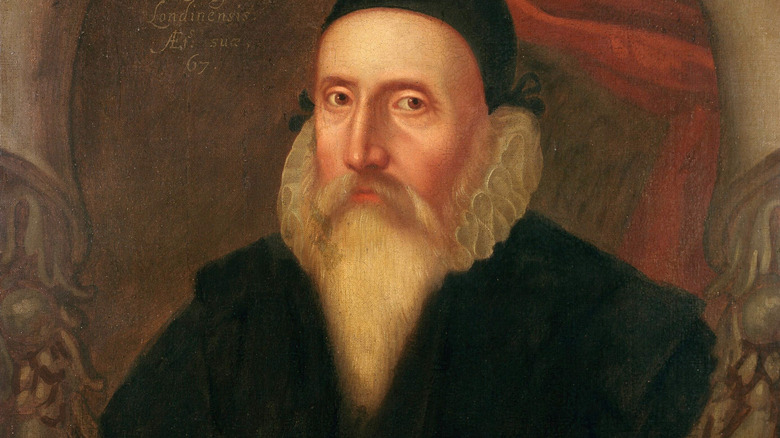

A born conjurer

"He that is a true magician, is brought forth a magician from his Mother's Womb; and whoso is otherwise, ought to recompense that defect of nature by education." These words, written by John Dee contemporary and author of "The Nine Celestial Keys," Thomas Rudd (per People Pill), perfectly encapsulate Dee's life and childhood. Born the son of a minor courtier in London in 1527, Dee grew up with a rapacious appetite for knowledge. As History Extra says, he slept four hours a night and spent his days studying scripture, the classics, mathematics, and the sciences, among other branches of knowledge. He'd bring all this knowledge to bear over the course of his life, a life so chimerical and expansive that its efforts resonate all the way to today.

Dee entered Cambridge at 15 years old, and developed a dual interest in stagecraft and the occult. ThoughtCo. tells us that he made a flying beetle for a production of Aristophanes' 421 B.C.E. comedy, "Peace." It was so awe-inspiring that the audience swore it was the work of sorcery rather than engineering, per the British Library. Dee, like many of his day, considered science, magic, and religion aspects of the same quest for knowledge and the divine. But finding pushback in his native England, he set off for the University of Louvain in modern-day Belgium and dove deeper into astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah, numerology, and more, as an article in the journal Studies in History and Philosophy of Science describes.

The original 007

John Dee came to royal attention and patronage through an unlikely means: getting arrested and charged for treason in 1553, as ThoughtCo. explains. At the request of the future queen, Elizabeth I, Dee had cast a horoscope about Elizabeth's sister, Mary I of England, aka "Bloody Mary." Mary I became one of the most hated monarchs in English history from 1553 to 1558, attempting to re-Catholicize England and burning hundreds of Anglicans at the stake, as History on the Net explains. It was the pious Mary, though, who set Dee free in 1556 and dropped all charges against him, per ThoughtCo.

When Elizabeth I became queen after Mary's death in 1558, she took Dee under her wing. He was "The Queen's Conjurer," and Elizabeth called him "my philosopher," per The Collector and Royal Museums Greenwich, respectively. Dee's myriad skills ranged from the purely scientific to the speculatively magical, and he became a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I. On one hand, Dee drafted reports on the British state, such as "Brytannicæ Republicæ Synopsis," or "Summary of the Commonwealth of Britain," which incorporated flowcharts regarding political and economic issues, as Royal Museums Greenwich says. His skills at cartography and geography helped him grow to great acclaim in the court, and he played a big role during an age of British exploration and expansion. As History Extra says, Dee even signed his letters to Elizabeth "007," an alchemically significant number that he intended to mean "for your eyes only."

Tongues of angels

John Dee, lacking the acclaim and funds he really wanted, receded from court life about 1580, as ThoughtCo. says. This let him dive into all the fringe, esoteric studies that he not only loved, but which help carry his legacy to the present. Esoteric Archives has a selection of the works he produced during this time. Dee turned to communicating with spirits most of all, and wanted to reach out to actual angels and learn the language of heaven. He called this language "Enochian," after the Biblical Noah's great-grandfather, Enoch (per New World Encyclopedia), and defined it as having its own grammar, vocabulary, and alphabet, as Ancient Origins explains.

During this time, Dee ran across a like-minded person, Edward Kelley. Kelley, as History Extra says, was a 26-year old with an alcohol problem whose ears had been cut off as punishment for counterfeiting. Dee, however, swore to Kelley's gifts at scrying, a magical practice that often involves staring into black mirrors — like Dee's own Aztec obsidian mirror on Art History Project — to alter consciousness and contact realms of spirits, as Hedingham Fair describes. Together, Dee and Kelley catalogued their scrying sessions in the form of "spirit diaries," per History Extra. Dee claimed to speak with "Good Angels" (per Ancient Origins) and drafted the Enochian language during this time. He also commissioned magical artifacts such as the Seal of God and the Four Castles Gold Disc, per the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic and Art History Project, respectively.

Trouble, tragedy, and heartbreak

On the heels of his angelic communication adventures with Edward Kelley, John Dee set out to travel across Europe and search for buried treasure. As historian Francis Young's website says, Dee wanted Kelley to wield his supposed scrying talents to find something perhaps even more valuable than the language of heaven: money. In 1583 Kelley came to Dee with red powder he called the "powder of projection," an alchemical component that Dee wanted. He also brought back a magical book for Dee to decode. The book, it turns out, was nothing more mysterious than coded Latin written by a couple of Danish princes. Dee, however — a bizarrely gullible person, per Occult World — apparently never realized that Kelley was playing him.

At this same time, tragedy struck Dee on multiple fronts. While on the way to Poland, Dee's house in Surrey, England got ransacked, per History Extra. Mysterious Britain states that not only did his manuscripts get stolen, burned, or destroyed by a mob who believed him to be a man with magical powers, so did his library of books, occult paraphernalia, and other belongings. Shortly after this the plague tore through England and killed his wife and four of his eight children, per History Extra. Dee took off for Prague, where after receiving a warm greeting from Holy Emperor Rudolph II, a man curious about the legendary alchemical philosopher's stone, Dee was kicked out by the pope on threat of imprisonment or being burned at the stake.

Rituals of the future

Even though John Dee stayed away from Queen Elizabeth I's court in his later years, he remained under her protection as his patron, and so could get away with things that might have marked others for suspicion. In fact, as History Extra explains, some believe that Elizabeth I used Dee as a traveling spy to gather intelligence on rival nations. If true, this could go far in explaining some of Dee's more odd choices. In a horrible twist of irony, though, it was Dee's possible library of intelligence — 2,670 volumes, almost six times that of his alma mater Cambridge — that got obliterated by the mob that ransacked his house. And when Elizabeth I died in 1603, there was no one left to shelter Dee. He died only five years later in 1608 (per Mysterious Britain), in poverty and trying to peddle his books and make money from creating astrological charts (per History Extra).

And yet, Dee leaves behind a lasting legacy in those very fields of inquiry that he adored: mysticism and the occult. Along with figures like Francis Bacon, Dee's multidisciplinary, oddly methodological, and even mathematical approach to magical studies influenced the development of Rosicrucianism in the early 17th century, as Sir Bacon describes. Rosicrucianism, in turn, helped give rise to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the late 19th century. Both organizations are active to this day, and show how the efforts of one person can reverberate through time in unexpected ways.