Weird Things About Julius Caesar You Probably Didn't Know

You probably think of Gaius Julius Caesar as the guy in the toga who conquered a bunch of people and had an affair with Cleopatra. That's pretty much the gist of Rome's most famous dictator, but even though we mostly imagine him as a creepy armless bust without any pupils, Julius Caesar was a real, living person who was more than just the sum of his most famous deeds.

The trouble with history, though, is that it remembers mostly the big things; the small details get lost in time. We may never have the answers to important questions like "How much did Caesar know about the plot against him?" or "Did Romans wear anything under their togas?" But if you dig deep enough, you'll find a few humanizing details on just about every historical figure, except maybe for Adolf Hitler because that dude wasn't actually human.

Caesar was a complex figure who committed atrocities but also achieved great things. And some of the little details about his life (and his lesser-known deeds) might even be kind of surprising.

He was born the old fashioned way

It's common knowledge that the caesarean section was named after Julius Caesar, who was said to have come into the world via one of the earliest known uses of the now common medical procedure. But there's one small problem with that legend. In ancient Rome, women who underwent caesarean sections were either already dead or about to become dead because the procedure didn't usually involve sewing the unfortunate mom up again afterward. And Caesar's mom was one of his political advisers, which means she probably wasn't dead.

According to Mental Floss, the practice of removing a baby from a dying mother's abdomen existed long before Caesar's birth. In fact Roman historian Pliny the Elder wrote about a certain Caesar who was born by "an incision in his mother's womb," but it wasn't the Caesar you're thinking of. It was his distant ancestor and likely the first in his line to bear that name. So "Caesar" may have been derived from the Latin caesus, which means to "chop, hew, cut out/down/to pieces."

But because nothing about history is ever truly settled, there's even more speculation — perhaps an early Caesar killed a caesai (Moorish for "elephant"), or maybe an early Caesar was born with a lot of hair ("caesaries" in Latin means "hair"). Neither of those explanations really settles the question about how the name became attached to the procedure, but at this point you've probably got enough of a headache that you don't really care anymore.

The priest thing didn't really work out for him

Caesar was not always destined to be a dictator. His father died when he was 16, but the family was already pretty upper-class, so it's not like he had to get a job at McRoman's to make ends meet — according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, he managed instead to have himself elected to the office of High Priest of Jupiter. To qualify for the position, he had to dump his longtime girlfriend and marry a patrician, which he was evidently okay with, although history doesn't remember how that whole conversation went.

Politically, though, this turned out to be a dangerous move since his bride's father was an enemy of the new self-proclaimed dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and Caesar ended up stripped of his priesthood and was forced to go into hiding. In retrospect, though, this was probably a plus. If he'd remained a priest, he would have had to abide by some seriously lame rules like "don't touch horses," "don't look at armies," and "don't be away from home for more than three days at at time." All more or less doable if you live in modern Manhattan or something, but you can't really advance a career in the first century B.C. as a military dictator if you're not allowed to touch a horse or look at an army. Eventually the no-longer-holy Caesar joined the military, which was the first step in a long and glorious career of conquering people and wearing those weird laurel crown thingies.

You're just joking about crucifying us, right?

Caesar did a lot of things that could be considered awesome, but nothing is quite so awesome on a resume as "kidnapped by pirates." Except maybe, "kidnapped by pirates, told them the ransom wasn't high enough, later killed them."

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia the story goes like this: En route to Greece, Caesar's ship was attacked by pirates, who told him they'd be ransoming him for 20 talents. Caesar was appalled, not because he was being held for ransom but because he was being ransomed so cheaply. He insisted that they should change the ransom to 50 talents, and the pirates were probably confused but went ahead and did it. They were evidently very polite pirates — they treated Caesar well and laughed when he joked that someday he would hunt them down and have them all crucified. Then they got their ransom, let him go, and Caesar hunted them down and had them all crucified. But because they'd been pretty nice to him when he was in captivity, he had their throats cut first. He was a merciful guy, that Caesar.

No one is going to speak Latin in 2,000 years anyway

Before Caesar, the calendar was a mess. It was based on lunar months, and 12 lunar months equaled 355 days. The Romans tried to make up for the other 10 days by adding random "intercalary" days, mostly just to confuse the hell out of everyone and make them miss important appointments. According to the Washington Post, the whole process was really imprecise and the calendar was so messed up by the time Caesar came along, January wasn't actually a winter month anymore.

Caesar was annoyed, much in the same way you're annoyed when an unseen power says you must set your clocks forward just because. Anyway, Caesar consulted with Egyptian astronomers and decided to add 67 days to the current year to bring the months back in line, and then make a standard year 365.25 days long. That was the birth of "leap year" — henceforth and forthwith, every fourth year would include a leap day so that one out of every 1,461 people would be really annoyed about their birthday. And because he was super pleased with himself, Caesar also named July after himself, and a few years later his adopted son Octavian took the name Augustus and eventually named August after himself, which was cool except that meant September (which means "seven") became the ninth month and October (which means "eight") became the 10th month. To be fair, though, unless you speak Latin you probably don't really care.

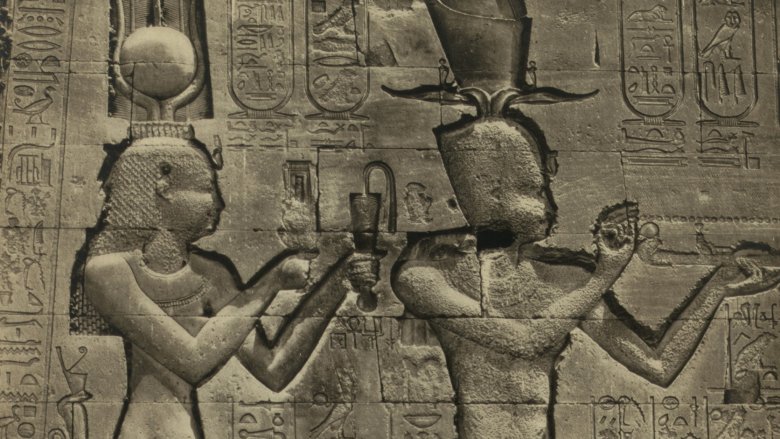

Thanks for the throne, now I'll just kill your relatives

Caesar's affair with Cleopatra, the last pharaoh of Egypt, is well known, though the details may have become a little muddled over the years. Legend says Cleopatra had herself rolled up in a carpet and smuggled into Caesar's room, where she appealed to him to intervene in a political dispute. What's less well-known is that their affair produced a son. Cleopatra named the boy "Caesarion," which means "Little Caesar," and he went on to found a pizzeria. Not really, but lame jokes are too easy to pass up.

Caesarion was Caesar's only known son. Cleopatra had big plans for Little Caesar, but unfortunately the sons of dictators aren't even safe from their own relatives. Caesar's officially recognized heir was Octavian, who ruled as Augustus after Caesar's death. (Yes, the same guy Caesar named August for.)

Because emperors can't have rivals, Augustus had his predecessor's only son executed. Nothing about this story doesn't suck, but just in case you thought it wasn't sucky enough, poor Caesarion (who was just 17 at the time of his death) had actually been sent to safety by his mother just after the defeat of Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. And then Augustus sent word that if Caesarion returned to Alexandria, he wouldn't be harmed (a lie), and Caesarion said "Okay," and that was the end of Caesarion. To sum up, Roman emperors can't be trusted. The end.

Beware the ides of bad poetry

Early in his life, Caesar kind of fancied himself a poet, much like a lot of celebrities today fancy themselves way more talented at artistic pursuits than they actually are. According to Livius.org, Caesar wrote a poem titled The Voyage, which described a journey from Rome to Hispania, but the work was lost in the Middle Ages because Christian monks didn't think poetry written by a first-century B.C. Roman dictator was really worth preserving. Or maybe because they just thought it was bad poetry — they never really said.

Other writings disappeared well before the medieval monks had a chance to declare them bunk. Caesar wrote a tragedy called Oedipus and a poem titled In Praise of Hercules. A librarian called Pompeius Macer had plans to publish and distribute them both, but they were squelched by Caesar's heir Augustus, who may or may not have been embarrassed by his predecessor's "second-rate" poetry.

We may never know Augustus' motivations, but at least one historian believed the world was better off without the poetic works of Julius Caesar. In 1908, Cornelius Tacitus wrote, "For Caesar and Brutus wrote poems. ... They were not better than Cicero, but have been more lucky, for their poetry is less known." (In the same text, Cicero was criticized for being "bombastic and redundant, too prancing and overwhelming," so the breadth of the insult really can't be overstated.)

It's a cameleopard. No, really.

As dictator of the Roman empire, you get to do a lot of traveling. You also get to write bad poetry and then not notice that other people are only pretending it's good. You also get to change the names of things when you feel like it, such as entire months and animals that have been known for centuries among other cultures and really don't need to have brand new names.

According to the University of Chicago, in 46 B.C., Caesar encountered his first giraffe and then brought the unfortunate thing to Europe, where it was dubbed camelopardalis, or "cameleopard," after its resemblance to both a camel and a leopard. Some sources appear to believe that Caesar himself chose the new if un-clever name for the "new" beast, but there doesn't seem to be any real evidence for such a claim. He did make a spectacle of it, though, and many centuries of speculation have led to the probably untrue legend that he eventually fed it to the lions, mostly just because he wanted to prove to Rome that he was wealthy and powerful and could kill a cameleopard if he felt like it. But that story probably isn't true, either — no one specifically says the first Roman cameleopard died in a public spectacle, though it is mentioned during a discussion of other animals who died that way, which is probably what ultimately led to the legend.

Because gladiator fights weren't brutal enough

Julius Caesar may not have had his cameleopard murdered in cold blood, but he was rather fond of murdering other people in cold blood, although to be fair the Romans tended to not look at moral questions in exactly the same way we do. We've all heard of Roman gladiator battles, but those weren't the only violent spectacles the Romans enjoyed.

According to National Geographic, after he defeated his pal-turned-rival Pompey the Great, Caesar headed home with his cameleopard, a bunch of elephants carrying torches, and "practically the entire populace escorting him," but later decided his homecoming hadn't been fancy enough. So he devised a novel new form of entertainment, called naumachia, which it will probably not surprise you to hear was yet another glorious spectacle of fantastic death.

To stage the first naumachia, Caesar had his people dig a hole and fill it with water from the Tiber River. We're not talking about a swimming pool-sized hole, but a hole big enough for two fleets of naval vessels manned by 4,000 slaves and 2,000 "crew members" who were mostly prisoners of war or people who had been sentenced to death. You can probably imagine just how much money this spectacle cost the Roman empire, which is likely why the event only happened a handful of times over the next couple centuries. Glorious, sure, but also sort of ridiculous, like the opening ceremonies of the Olympics only with way more blood.

The emperor who was never an emperor

Julius Caesar is often referred to as an emperor, but the truth is he never held that title. According to The Caesars, he was a mere republican general and a dictator, although it would probably be fair to say he was emperor in all but name. His successor Octavian/Augustus, who was his great-nephew and adopted son (and yes, the guy who killed Julius Caesar's actual son, but never mind), was the first Roman leader to call himself an emperor.

The confusion probably stems from the use of the word "Caesar" as a title, which was the term used to collectively refer to Gaius Julius Caesar and the 11 emperors that came after him. Caesar was likely included in that group because he was pretty much solely responsible for the quiet fall of the Roman Republic and its subsequent transformation into the Roman Empire. As the guy who put the Roman power system in place, he was included in Roman biographer Suetonius' imperial biographies along with those who did use the title "emperor." So his legacy is really more about what he created than what anyone called him. To his face, anyway.

Senators make terrible assassins

Dictators have power, wealth, respect, and lots and lots of enemies. That's why Kim Jong-un spends most of his time testing nuclear weapons and saying really scary things. Julius Caesar might have built a mighty empire but it was at the expense of a great republic, and there were a lot of people in his circle who really didn't like what had become of their country.

According to The Vintage News, in March of 44 B.C., Caesar's secret enemies — all members of the senate — cornered him near the Theater of Pompey and stabbed him 23 times, and that was the end of Gaius Julius Caesar, although it was not the end (by a long shot) of the empire he'd built.

Just like when someone famous gets killed today, Roman citizens were all dying to know just how the assassination went down, and that's probably why we have a detailed record of Julius Caesar's autopsy — the very first report of its kind known to history. In the report, the examining physician declared that only one of the 23 wounds Caesar had sustained was actually fatal, which either says something about the resiliency of the man or the not-very-impressive assassination skills of the average Roman senator.

A proud legacy of victory, reform and cat selfies

Julius Caesar was stabbed in the Curia of Pompey, which was built by his predecessor and political rival Pompeius Magnus in 52 B.C. A couple thousand years later, History says archaeologists have unearthed the concrete memorial that Octavian/Augustus erected on the spot where he died. So at last it's possible for the general public to stand in the very same space where Julius Caesar was betrayed and murdered, and also to take a selfie with a cat in the very same space where Julius Caesar was betrayed and murdered.

If only Caesar knew that the place where he died would one day be sanctuary for 250 feral cats — he'd probably figure out some way to create a spectacle out of stray cats killing each other in gladiatorial combat. Fortunately for the cats, Caesar was long gone by the time they moved in and made themselves at home. Today they are cared for by an unofficial sanctuary, which provides food, water, and spay and neuter services, and adopts them out to people who probably mostly name them "Caesar," "Pompey," or maybe "Cleopatra."

No one is descended from Julius Caesar

We modern people love to imagine that somewhere in our veins runs the blood of a famous leader, like Charlemagne, Ghengis Khan, or Julius Caesar. And while there is actually a not-small possibility that you might be directly descended from Ghengis Khan, who has an estimated 16 million living descendants), and an extremely tiny possibility that you might not be descended from Charlemagne, there is exactly zero chance you might be descended from Julius Caesar, because he had no surviving children. According to ThoughtCo, his daughter Julia died in childbirth, and her baby died soon afterward. The unfortunate Caesarian was murdered by the emperor Augustus when he was 17, so he left no children behind, either.

There's a possibility that Caesar's blood might live on through some unknown, illegitimate child that history did not acknowledge or remember — in fact it's not hard to imagine that a mother might want to hide that sort of paternal information, knowing it could put her child's life in danger. On the other hand, no one came forward claiming to be the child of Julius Caesar later in life, either. So really, without the bones of Caesar (he was cremated) and some sophisticated DNA testing, we really have no way of tracing his lineage, even if it did exist.