The Biggest Misconceptions About The Black Plague

The Black Plague (or Black Death) was the name given to the bubonic plague pandemic that devastated Europe in the 14th century (per History). The plague arrived in Europe via ships docking in Sicily, and local populations were unable to stop its quick spread throughout the continent — in just a few years, from 1347 to 1351, the plague killed over 20 million people, or at least 30% of the population at the time. Some sources believe the numbers were much higher — the American Association for the Advancement of Science estimates up to 60% of the population in Europe might have succumbed to the Plague, and both London and France lost at least half of their population. In fact, mortality in cities was especially high, as isolation was almost impossible (via Britannica). Rural communities fared somewhat better, but even monasteries and royal residences couldn't escape the infection — Joan, the daughter of Edward III, and several cardinals living in Avignon all succumbed to the plague.

It wasn't until 1885 that scientist Alexandre Yersin discovered the Yersinia pestis bacterium as the cause of the plague (via Institut Pasteur). Once antibiotics were invented, the plague became very treatable. But people getting sick in the 14th century weren't as lucky. Back then, the infection quickly spread in the body, causing vomiting, diarrhea, and swollen lymph nodes before progressing to a massive blood infection (sepsis) and organ failure, according to ScienceDirect.

The disease was caused by rats

Rats — and especially rats traveling in ships — have long been blamed for spreading the plague, but this theory might be finally put to rest. For centuries, scientists have believed that infected fleas jumped from rats to humans in dirty, crowded towns, transmitting the infection and helping spread the plague (via History). But researchers have been questioning this theory for some years now.

For example, a 1986 paper published in The Journal of Interdisciplinary History points out that rats aren't mentioned in historical records of the plague, and they were also not as common in towns as one might think — at least not to the level required for the plague to spread so quickly. Even if infected rats arrived on ships, researchers believe they would have probably stayed around the port area rather than making their way into cities.

So if it wasn't flea-carrying rats that spread the plague, how did it happen? A newer study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal points the finger primarily at human lice and fleas instead. The very fast speed at which the plague spread makes more sense if contagion was passed directly from person to person (as fleas jumped among members of a household, for example).

This would also explain why the plague was present even in European cities where the rat population was almost nonexistent, according to The Journal of Interdisciplinary History.

Advancements in transportation helped the spread of the Plague

One of the reasons the plague was so deadly for Europe is that it moved at an alarming speed. At its worst, it was traveling at a speed of 24 miles a day, reaching new towns and cities faster than anyone could imagine (via National Geographic). But the speed had little to do with transportation itself — in the 14th century, people moved using mostly horses or just walked long distances, covering an average of 20 miles a day (via Encyclopedia.com). This means the plague was moving at their speed or even faster.

Experts believe the fast movement of the plague through Europe in the 1300s was more likely connected to the growing trade. With the Silk Route providing both land and maritime routes to connect continents, it was easier for the plague "to catch a ride" and show up at foreign ports quickly. With cities growing significantly, the plague was also able to infect larger populations quickly, which could then pass it on as they moved to other cities and towns or traveled to pilgrim sites.

When the plague came back in the 17th century, it moved significantly faster than the 1300s Black Death. According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this again wasn't a result of better transportation systems, but likely related to higher population density, poor living conditions, and even changes in the weather.

People were unable to do anything to stop the plague

Actually, they did quite a lot. We owe the word "quarantine" to the Italians, who during the Black Death implemented trentino (30-day period) and quarantino (the word for a 40-day period) to try to protect their population. Both Milan and Venice had strict measures in place to try to survive, but Milan in particular took things to a completely new level (per History). According to a Washington Post article by historian John Mulhall, Milan came up with a plan to isolate the sick, established quarantine measures, and kept pilgrims and travelers outside the city gates. They also had doctors monitoring the health of the population and keeping death records.

Another city that pulled all the stops when it came to fighting the plague was Dubrovnik. Back in the 14th century, Dubrovnik (present-day Croatia) was known as Ragusa and under Italian rule. Ragusa was part of the area that experienced a new outbreak of the plague in the 1370s, about 20 years after the main Black Death outbreak. As a response to it, the city passed a law to force ships coming from known plague-infested areas to spend 40 days offshore, waiting out the infection cycle before they were allowed to disembark. By the turn of the century, the city also had health officers patrolling, guards at the city gate, a team of gravediggers, and a system to penalize those breaking "plague laws" (via Bulletin of the History of Medicine).

The nursery rhyme Ring a Ring o' Roses is about the plague

You've probably heard somewhere that this famous nursery rhyme is really about the plague, but the truth is that folklorists aren't so sure. The rhyme goes like this: "Ring-a-ring-a-roses / A pocket full of posies / A-tishoo! A-tishoo! / We all fall down."

For those who claim the lyrics are about the plague, the ring of roses refers to a rash, and the third line is about the sneezing connected to being ill. The falling down is a direct reference to dying from the plague. The problem with this interpretation, according to folklorists, is that it is too new. In fact, a connection to the plague first appears in print in "The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes" (via Library of Congress' Folklife Today) by Iona and Peter Opie in the early 1950s. But the Opies didn't believe this was a valid reference, and other experts have agreed since then.

In addition, while the most famous version of the rhyme (posted above) could potentially imply something sinister, there are many "happier" versions around. In one version, lines 3 and 4 are replaced by "The one who stoops last / Shall tell whom she loves best," while in another, the song ends with "All the girls in our town / Ring for little Josie." Neither one seems to have any connection to the plague, so where does the mysterious connection come from? Not even researchers know. Maybe the dark connection is just too fascinating to let go.

The plague lasted for only a few years in the 14th century

Most people associate the Black Plague with the pandemic that swept through Europe in the 14th century. But the plague had already devastated the world long before that, starting in the year 541 A.D. with the plague of Justinian, which ravaged Constantinople and killed at least half its population before causing chaos all over the Mediterranean (via Britannica). Historical records from the time are vague regarding the death toll, but researchers think the Justinian plague could have killed as many as 100 million people.

A 2014 study published in The Lancet confirmed that Yersinia pestis (the plague bacterium) was responsible for all three of the major plague pandemics: the Justinian plague, the 14th century Black Death, and a third pandemic in the 19th century. The plague has never disappeared, and it has continued to reappear throughout Europe and Asia through the centuries. In fact, the bubonic plague still exists, and cases are still found throughout the world. Between the years 1970 and 2020, the CDC reports 496 cases of bubonic plague infection were reported in the U.S., mostly in Western rural states.

Although the bubonic plague can now effectively be treated with common antibiotics, deaths still occur. Recent outbreaks around the world include over 100 cases and 13 deaths in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2021 and almost 60 suspected and confirmed cases in Madagascar in 2021, where the plague causes up to 700 infections every year (via Gov.uk).

Plague doctors wore their famous beak masks in the 14th century

Plague doctors are a very well-known image associated with the plague. Their bird-like beak masks and head-to-toe black outfits are hard to ignore — and so are the descriptions of them walking the streets of medieval cities to attend to the infected. But the truth is that plague doctors did not exist during the Justinian plague or even the 14th-century Black Death pandemic. They actually don't appear in literature at all until the 17th century, when physicians started wearing the costume in an effort to protect themselves against infection during an outbreak of the plague in Paris (via Live Science).

The outfit is credited to royal physician Charles de Lorme, who in the early 1600s designed a seemingly-impenetrable costume that consisted of a coat covered in wax, tall boots, goat leather hat and gloves, and a long rod that they could use to push away the infected if they got too close. The most famous part of the outfit (the beaked mask) was actually hollow so doctors could insert theriac into it. This mix of herbs and medical compounds was supposed to filter out the infection and protect the plague doctors (per National Geographic). Spoiler alert: it didn't work. That's because doctors weren't looking to filter out bacteria but "evil smells," which they thought were making people sick (via Hardin Library for the Health Sciences).

The plague was so deadly, it killed people of all ages and health conditions

With antibiotic treatment, the bubonic plague is fairly easy to treat today, and most people recover well. But without access to antibiotics, the plague kills up to 60% of those infected, according to the World Health Organization.

The Black Death was so deadly and killed so many millions that for years scientists believed it killed indiscriminately, taking the young and the old, women and men from all walks of life. But a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal showed this actually wasn't the case. When scientists looked at remains from London's East Smithfield Black Death cemetery and compared them to skeletons pre-plague, they discovered the plague had actually been quite selective.

They found that out of the almost 500 skeletons studied, many showed signs of "frailty," or signs of things like lesions of the skeleton, signs of malnutrition, and changes in the bone that could indicate stress or prior infection. From this, scientists deducted the plague was more likely to kill people in the "frail" category — those who were already in somewhat poor health when they got infected with the plague. At a time when few simple diseases could be treated properly because of a lack of medications, frailty could affect anybody, even the young.

Everybody believed the plague was a punishment from God

The 14th century was a time of superstitions mixed with intense religious beliefs. When the plague started to spread and caused massive casualties, it's no surprise that the population held on to their beliefs and proclaimed the plague was a "punishment from God." To be saved and healed, believers thought they needed to ask forgiveness and cleanse their environment (via History). This took many forms — from processions of traveling flagellants beating themselves in public to "save" different towns to the massacre of Jews in Germany in the years 1348-1349 because they were considered to blame for the spread of the disease, according to a paper published via Brigham Young University.

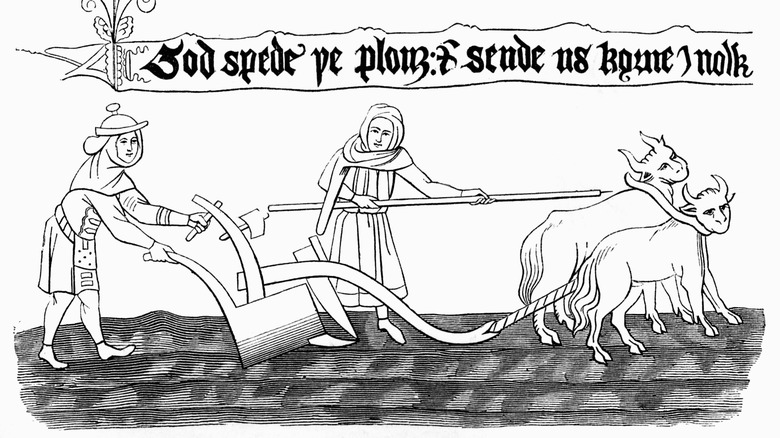

While peasants might have been lost in their "punishment theory," doctors were trying to rely on medicine to deal with the plague. In the 14th century, medicine was based on the theories of "humors," where all diseases were connected to bodily fluids such as blood, bile, and phlegm (as explained via a paper published by researchers from James Madison University). With little medication at their disposal, all doctors could do for plague victims was to prescribe things like burning scented wood, bathing in rose water, and bloodletting to fight the "miasma" (bad air) they believed was causing the infection.

The black plague was a European disease

Although the Black Death ravaged Europe, it actually started in Asia years before it arrived on the Italian coast. More specifically, historians believe the plague spread following the Silk Road, a series of roads and trade routes (both on land and water) that connected China with Europe and Turkey (per History).

In a new 2022 study published in Nature, scientists have now identified what could possibly be the origin of the plague strain in Kyrgyzstan, where DNA from bones dating back to 1338 tested positive for Y. pestis, the bacterium that causes the plague. The ancient Central Asia strain, near the Tian Shan mountains, could potentially provide a definitive answer regarding where the plague really started. During a few devastating years, the plague extended its grasp all the way from Asia to the Middle East and Northern Africa, where it likely killed as many people as it did in Europe (via History).

A few years prior, German scientists also found evidence of the plague happening in 1346 in Russia's Lower Volga regions, a year before it reached Europe, confirming, at the very least, that the plague arrived in Europe from the east (via Nature). History researcher Gérard Chouin with William & Mary University is adamant that the 14th Black Death also reached Sub-Saharan Africa, killing millions along its path. Historical sources are less accessible in the area, and Chouin continues to search abandoned settlements and other archeological finds to confirm this theory.

The plague killed only people

Not much has been written about the death of animals during the Black Death, but there's no doubt many died alongside farmers or pet owners back then. The CDC lists many animals that can be infected with the plague, including squirrels, mice, and rabbits. Cats can then get infected by eating rodents. Back in the 14th century, rural populations also had farm animals to worry about, as the plague-infected cows, pigs, and chickens — and anybody dealing with them — could potentially be infected as a result. In fact, so many sheep died during the plague that Europe suffered a significant wool shortage for years to come (per History).

In the book "The Decameron" (via Fordham University), 14th-century Italian and poet Giovanni Boccaccio describes the scene of seeing two pigs smell the clothes of an infected person and then dying on the street soon after. And in her book "The Black Death," Rosemay Horrox shares how Franciscan Michele de Piazza noted that "not just one person in a house died, but the whole household, down to the cats and the livestock, followed their master to death."

This wasn't a new thing, either. Speaking about the Justinian plague, Greek historian Nicephorus Gregoras wrote (per "The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350"), "The calamity did not destroy men only, but many animals living with and domesticated by men. I speak of dogs and horses and all the species of birds."

The plague was already known as black death in the 14th century

The plague made three major appearances throughout history and had a different name every time. The first recorded instance of the plague in 541 A.D. is known as the Justinian Plague, named after Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. This plague devastated Constantinople and killed millions, but it seems to have mostly disappeared by 590 (per Britannica). When the next major plague pandemic happened in the 14th century, it was simply known as "the pestilence." There are theories about the origin of the name, including the possibility it referred to the hemorrhage and gangrene that sometimes developed from severe infection (via the Journal of Military and Veterans' Health).

The name "Black Death" does not appear on record until many centuries later. In the book "The Complete History of the Black Death," author Ole Jørgen Benedictow guesses the name could be from the Latin expression "atra mors" (with "atra" meaning "black/terrible" and "morns" meaning "death"). But the name was being used by other scientists at the time, including French physician Simon de Covino, who called it "mors nigra" ("black death"). There's no official name for the third plague outbreak, though 19th-century sources in both English and Spanish literature often refer to it as "the black death," too.