Here Are The Oldest Known Surviving Books In The World

Sometimes it's possible to look around at humanity and be absolutely amazed of our survival — long enough to build a civilization that's several thousand years old. Through wars, pestilence, and so many poor decisions it's hard to list and quantify them all — humanity has persevered in the face of our own idiocy against all the odds.

That's one reason the physical evidence of our durability is so fascinating. Seeing things made by humans who lived centuries ago it brings home the fact that humans are the leading edge of an incredible story. These artifacts are also the lasting legacy of people who lived just like us, who worked and loved and struggled. While its hard to know their specific stories, there is at least some glimpse of their lives through what they left behind.

Old books are a special example of this. No matter their subject, books are personal, and imagining someone writing and reading a book hundreds — or even thousands — of years ago is a humbling and mind-blowing idea. When contemplating the oldest known surviving books in the world, it's helpful to define the term — a book isn't just writing, a stone tablet, or a scroll. It's a collection of pages bound together somehow to create a distinct object. Although the printing press dates back to the ninth century, as per History, there are books that are much older than that.

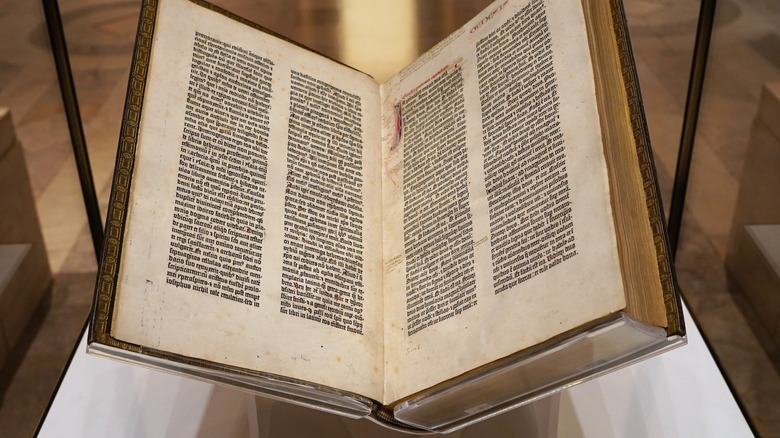

Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible holds the record as the oldest "mechanically-printed" book, according to Guinness World Records, dating back to 1455 (although Britannica notes that a Korean book was produced using movable type about 80 years earlier). According to the New York Public Library, Johannes Gutenberg invented the system of movable type printing that enabled him to produce exact copies of a book over and over again. It revolutionized printing and publishing, and the first book he produced was a copy of the Bible.

As the embodiment of the "lots of copies keep stuff safe" (LOCKSS) concept, there are still 48 copies of the Bible in existence after nearly six centuries — although The British Library notes that of those only 20 are complete. Interestingly, many of the existing copies have had hand-drawn illuminations added, giving the books the illusion of being hand-copied like older books. In fact, the Bible deliberately does not include page numbers or a title page in an apparent effort to maintain that illusion. What's truly remarkable about the Gutenberg Bible is how high-quality it is: For a first effort, it is well-designed, very readable, and has aged remarkably well.

The Miroslav Gospel

According to historian Christopher Deliso in the book "Culture and Customs of Serbia and Montenegro," the Miroslav Gospel isn't just one of the oldest books in the world — dating to about the year 1180 – it's also one of the first surviving examples of Serbian literature. It's written in a transitional language that captures Old Church Slavonic evolving into Serbian, making it an important historical document.

The book was commissioned for Miroslav of Hum, brother of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja. It survives today in incredibly good shape in large part because it has been kept at an isolated monastery for much of its history. In 2005, UNESCO added the Miroslav Gospel to its Memory of the World list, which is designed to preserve and provide access to the historic and cultural documents.

The book is 362 pages long and contains some stunning art — unusually, the identity of at least one of the scribes who created the book has been discovered. According to historian Florin Curta in the book "Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300)," a scribe named Grigorije is actually credited in the book itself.

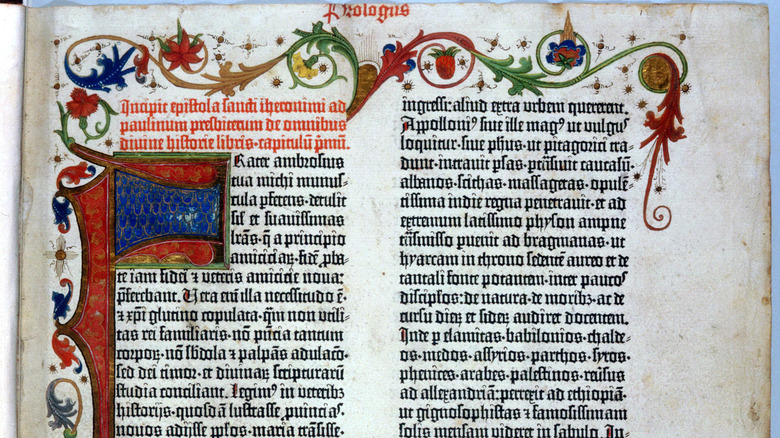

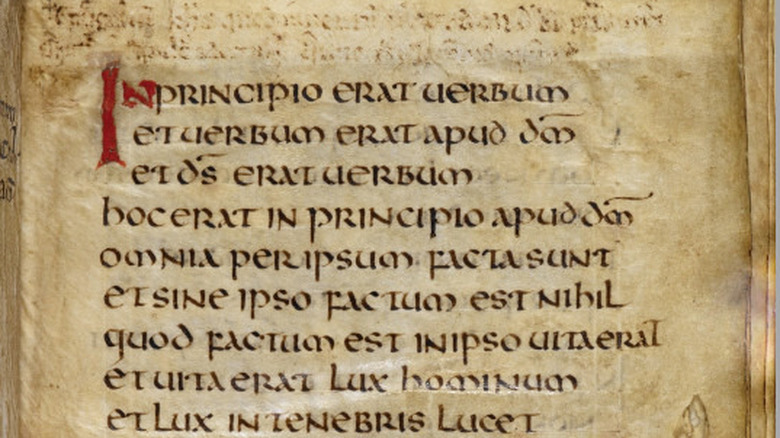

Celtic Psalter

According to BBC News, the Celtic Psalter isn't a printed book but rather a handwritten collection of psalms written in Latin. It was probably commissioned by someone wealthy and important, because it's beautifully illuminated in a wide range of vibrant colors — one candidate for its sponsor is St. Margaret, who was queen of Scotland in the 11th century, based on the "English" style of its decoration. Because the book has been carefully stored and kept out of the public eye for centuries, it's still in great shape. The binding is gone, but the pages themselves are clear and crisp. The book is pocket-sized, as it was probably intended to be carried around by the owner.

According to The Scotsman, most experts believe the Psalter was made by monks at the Ioan Abbey, located on an island off the Scottish coast. (These monks also worked on another famous old book, the Book of Kells). The University of Edinburgh notes that the book suddenly appears in the university's records in 1636, but nothing is known of its location prior to that although there are some hints that it may have resided in Aberdeen for a while.

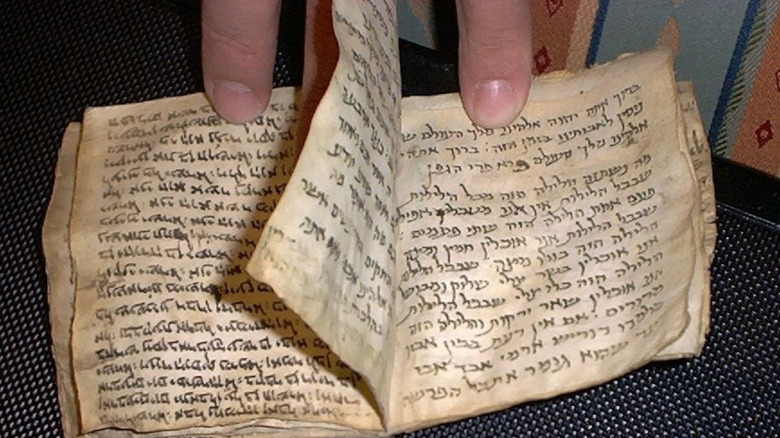

Siddur, Jewish Prayer Book

The Associated Press reports that the oldest Jewish prayer book (called a "siddur") still in existence actually still has its original binding. Carbon-dated to the year A.D. 820, the book represents a shift in how Hebrew documents were kept — until about the sixth century, they were typically recorded on scrolls. According to Israel National News, the siddur is so old it is written in a very antiquated form of Hebrew that uses what's known as "Babylonian vowel pointing," a system of marks above letters to indicate vowels or pronunciation.

According to The Times of Israel, however, some experts have raised doubts about the true age or composition of the book. The pages are of slightly different sizes and written in different handwriting, and the content is a disorganized collection of poems, prayers, and other writings leading some to wonder if the pages weren't collected from other sources and bound together at some point in history. While the carbon dating seems to confirm that the pages of the book are indeed very, very old, it's possible that it was not originally a book as defined today but rather a random collection of writings that were bound together at a later date. Until that's proved, however, it remains one of the oldest surviving books in existence.

[Featured image by מוישה רוזנפלד via Wikimedia Commons | cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

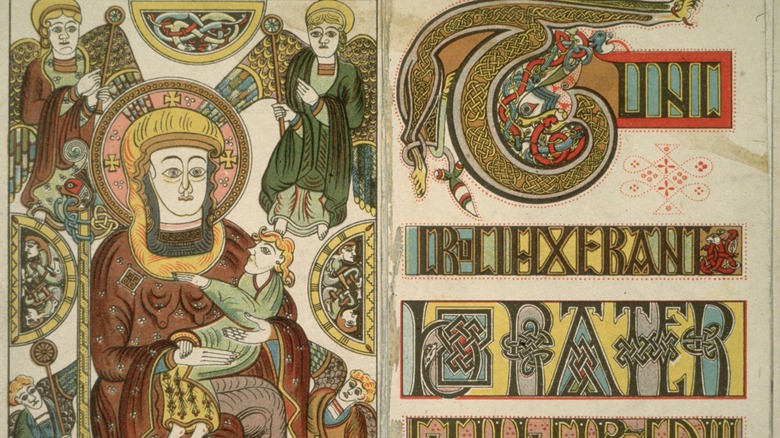

Book of Kells

According to Britannica, the Book of Kells (described by Lithub as a book containing the four Gospels) is a classic work of the decorative vocabulary style known as "Hiberno-Saxon." This describes the artful way the letters of the manuscript are ornamented with curves, spirals, and other beautiful, hand-drawn shapes.

As BBC Culture reports, the Book of Kells was likely begun at a monastery on the Scottish island of Iona, and experts believe it was probably completed there by about A.D. 800. It was transported to a monastery in the Irish town of Kells after a Viking raid hit Iona in the year 806. The Book of Kells continued to have a pretty adventurous existence: In the year 1006 it was stolen and buried for a little more than two months, and during the English Civil War the church in Kells where it was kept was nearly destroyed, at which point it was sent to Dublin where it was eventually added to the collection at Trinity College.

And yet, incredibly, the Book of Kells is in great shape — although it's missing about 30 folios (60 pages), it was used for rather secular means: as a record book for business dealiings. And at some point it had a poem added to it in the 1400s (per Trinity College).

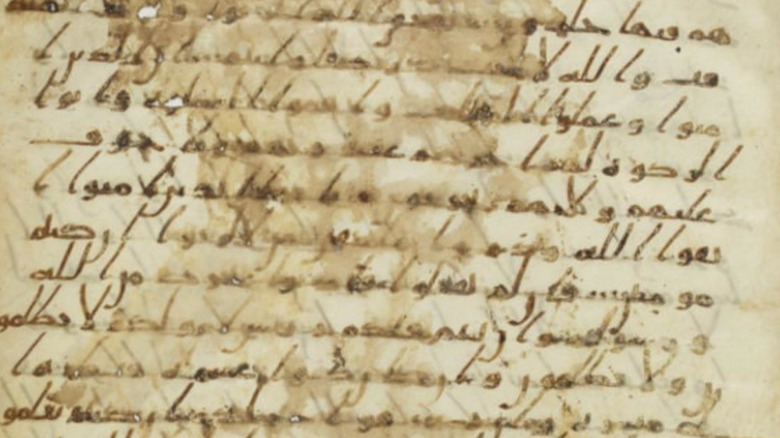

Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus

As noted by historian Daniel W. Brown in the book "A New Introduction to Islam," the Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus is one fo the oldest surviving manuscripts of the Qur'an and has been dated to the seventh century. (In fact, according to author Mun'im Sirry in the book "Controversies over Islamic Origins," the Codex might date back to the late sixth century, based on carbon dating tests.) One of the most important aspects of the Codex is that it demonstrates that the basic text of the Quar'an had been largely settled by this time, although changes would continue to creep in.

According to historian François Déroche in the journal Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, the Codex was kept in the Amr Mosque in Egypt until the late 1700s, when the French expedition under Napoleon took several pages. Over the next few decades more and more of the Codex was sold and transported, so that today its pages can be found all over the world. As noted by Francois Déroche in the book "Qur'ans of the Umayyads," one of the most interesting aspects of the Codex is the fact that it was created by at least five different copyists, who each used their own system of punctuation, according to "The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies."

St. Cuthbert Gospel

Modern-day digital technologies like eBooks are pretty incredible and offer a lot of convenience, but they really don't improve much on the printed book in terms of durability. Digital files can be deleted and devices can crash, but as NPR notes, a book that's centuries old can be in like-new shape if properly cared for. The St. Cuthbert Gospel, a small, leather-bound book from the seventh century, looks like it was created just a few weeks ago despite its age.

According to the British Library, the book was already pretty old when it was initially discovered in the year 1104. The gospel had been placed inside the coffin of St. Cuthbert, who died in 687 — though the gospel was likely placed there later, when Cuthbert was made a saint. Interestingly, the gospel was probably not bound into a book initially.

JSTOR notes that the gospel is so well-preserved in large part because of its association with St. Cuthbert — having been found in his coffin when he was elevated to sainthood in the Catholic Church, the gospel was considered a holy relic and would have been treated with extreme care. Holy books like this were also considered to have protective powers and were often carried or worn on the body to stave off danger, as per Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural, which would have inspired great care when handling the book.

The Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius

While many of the oldest books still in existence have religious content, proving the importance of spirituality throughout the history of mankind, books have always been used to convey all kinds of information. For example, according to My Modern Met, one of the oldest books in the world is a herbal (a collection of plant and medical information) believed to be an adaptation of material originally written by in the fourth century by Roman naturalist and philosopher Pliny (specifically his "Historia Naturalis") and Discorides's "De Materia Medica," although the oldest copy dates to the sixth century.

What's remarkable about the book is the truly fantastical illustrations it contains — vibrant, colorful, and often highly fictional depictions of plants. The book was copied many times during the Middle Ages so there is a great deal of variation between the versions, some of which can be viewed online at the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

According to author Emma Kay in the book "A History of Herbalism," the book is called the "Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius" because it was originally attributed to the Roman writer Apuleius of Madaura, but today it is believed to be the result of several authors. It's also sometimes called the "Herbarium Apuleii Platonici" because the work spends a lot of energy demonstrating how certain herbs and plants are aligned with the planets and astrological signs.

[Featured image by Wellcome Library, London via Wikimedia Commons | cropped and scaled |CC BY-SA 4.0]

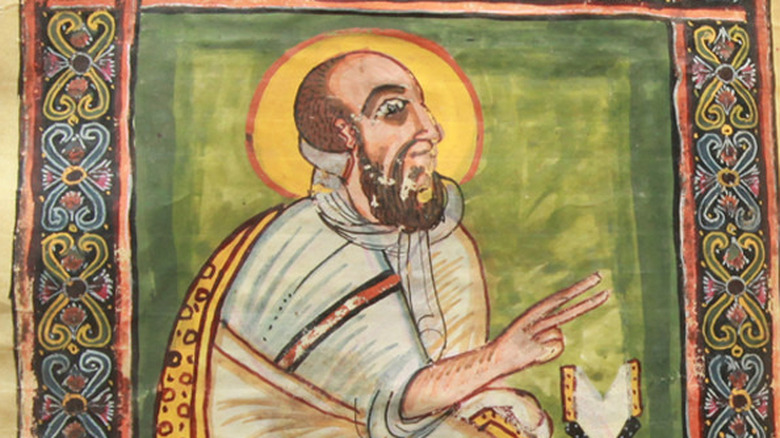

Gärima Gospels

According to The Independent, for many years it was believed that the two books containing illuminated versions of the four gospels of the Bible held at the Abuna Gärima monastery in Ethiopia dated back to some time in the 11th century. But new information revealed after carbon dating the manuscript places the Gärima Gospels in the fourth century, and probably no later than the mid-seventh.

Aside from their age and the great beauty of the illuminations inside, The Daily Beast notes they are unique because they include portraits of not just the four evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, but also a man sometimes called the "fifth evangelist," Eusebius of Caesarea. Eusebius was a bishop in the fourth century, and he is largely responsible for organizing and cross-referencing the four gospels, allowing people to easily make connections between what were isolated stories that sometimes contradicted each other.

Another remarkable aspect of the gospels is the fact that they have been located in the same extremely isolated monastery for their entire existence. In fact, when the monks decided that the books needed to be restored in 2010, the bookbinder they engaged for the work wasn't allowed to take the books away and had to travel to the monastery and work on-site.

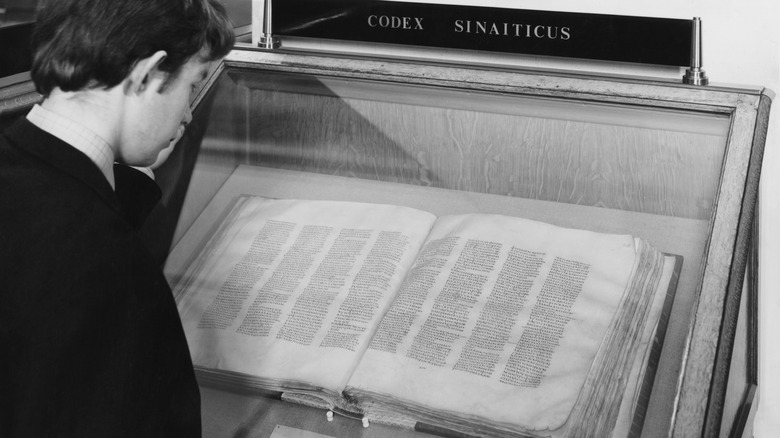

Codex Sinaiticus

While the Gutenberg Bible may be the oldest mechanically-printed Bible in existence, the oldest Bible overall is much, much older. According to the Britannica, that would be the Codex Sinaiticus, which dates back to the middle of the fourth century. As noted by the British Museum, while the version of the Codex in existence today is missing some portions of the Old Testament, it originally contained the full text of the Bible.

Three or four scribes worked together to produce the manuscript, which not only is missing several portions of the gospels but also has a large number of corrections marked throughout. These corrections were added much later and represent an attempt to bring the Codex into line with what had become the standard version of the Bible text — according to The Guardian, there are close to 27,000 corrections in total. It's one of the earliest known bound books, as well — prior to the Codex most written works were produced on scrolls or small folded booklets.

The Independent notes that one big reason this ancient Bible has survived into the modern day is the fact that it was stored for centuries in the Monastery of St. Catherine, which was built at the base of Mount Sinai in Egypt. The climate there is dry and warm, ideal for preserving the vellum parchment the Codex was written on.

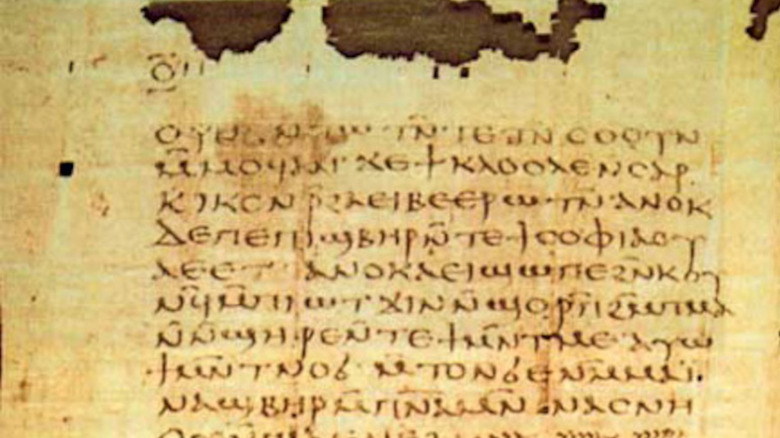

Nag Hammadi Library

As you might guess from its name, the Nag Hammadi Library isn't just one book, but several — 13 in all, according to author Marvin W. Meyer in the book "The Gnostic Discoveries." The books were discovered near the town of Nag Hammadi in Egypt in 1945, and an article in Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints notes that they have been dated to the fourth century, although some of the texts they contain are copies of much older works. According to the Los Angeles Times, the Library also contains several apocryphal Bible gospels, including the Gospel of Thomas.

According to The Journal of Library History, one reason the Nag Hammadi Library is so important is that it contains what are known as "Gnostic" works. Gnostiscm was a religious movement in early Christianity that emphasized secret knowledge that would lead to salvation.

Almost as interesting as the historical importance of the Nag Hammadi Library is the mystery surrounding its discovery. As noted by the New York Review of Books, the Library was discovered by Muhammad 'Ali al-Samman and his brothers in a network of caves. The brothers eventually sold the books and told stories that included a murder, fear of police searches, and other fantastic details that the Journal for the Study of the New Testament notes have come into serious doubt over the years.

Etruscan Gold Book

The oldest book still in existence admittedly pushes the definition of the word "book" to its limits. Known as the Etruscan Gold Book, BBC News reports that it's believed to be millenia old. It's composed of six sheets of solid gold worked with illustrations that are bound together into a book by a metal binding.

There are other, similar gold "pages" still in existence, but none of them show any sign of having been bound together into what an expert at the National History Museum in Sofia, Bulgaria called "the oldest comprehensive work involving multiple pages." The plates also contain words written in the Etruscan language. Incredibly, after finding the ancient — and priceless — book in a tomb, the anonymous discoverer donated it to the National History Museum and has never been identified.

Author Oliver Tearle notes in his book "The Secret Library" that no one knows what the words in the Etruscan Gold Book say — because the language has never been deciphered. Britannica explains that since there are no languages that are in any way related to Etruscan, it remains very unlikely that it will ever be translated. Until then, the world's oldest existing book will hold its secrets.

[Featured image by Ivorrusev via Wikimedia Commons | cropped and scaled |CC BY-SA 4.0]