Ancient Languages That Completely Disappeared

When an ancient language's last breath is uttered, it's usually because a younger, hotter and more socially and economically viable one has come along to grab everyone's attention. Some are still uttered plenty beyond the grave; Latin and Ancient Greek are like the popular kids who arrive to their high school reunion in Lamborghinis and brag about their trust funds while Old Norse sulks in the corner nursing his fifth Bud Light. Many survive in remnants of the languages we use today, while some remain the subjects of great scholarly fascination. And then there are some that disappear without much of a trace.

The truth is, what's lost when a language disappears is a whole lot more than just, say, an exotic way to order coffee. Unique cultures, whole bodies of ancient knowledge, and intangible links to heritage stand to disappear along with the words. Around 400 languages have gone extinct over the last century alone, according to the BBC, and it's estimated that half of the world's remaining languages will bite the dust by the end of this century. There are people fighting the good fight and instigating strong revival efforts, but the magnitude of loss that comes with an ancient language's disappearance bears highlighting. We English speakers will know all about it as soon as people resort to communicating exclusively through emojis and Ru Paul's Drag Race reaction gifs.

Norn: the Vikings' gift to the Northern Isles of Scotland

When the Vikings weren't braiding each other's beards and pillaging left right and center, they were settling in towns and villages that actually welcomed them relatively peacefully. Take the Shetland and Orkney islands of Scotland, for example, where Vikings set up camp around 800 A.D. and found a shared culture among the local populace, according to The Telegraph. Probably eager to compare mutton stew recipes and share plundering tips with their new neighbors, the Vikings introduced Norn, a language evolved from Old Norse and spoken exclusively on these islands and some parts of north Scotland's mainland for centuries.

As Scottish rule gradually started to influence life on the islands and Scots English took over as the predominant tongue, Norn began to disappear, but exactly when it became extinct is up in the air. Most people think a guy called Walter Sutherland, who died in 1850 and who may have lived in the northernmost cottage of the British Isles, was the last speaker. There are still some remnants of Norn in the modern dialect of the Shetland Islands, so locals can still have a bit of fun messing with confused tourists asking for the time or the nearest bathroom. What more could you really want?

Etruscan: Latin's older and much less popular cousin

No matter how great he was, Joe Frazier's legacy will always reside in the shadow of Muhammad Ali's. Deep Impact will always be a footnote to Armageddon's success. And so it is with Etruscan and Latin, even though both languages were spoken in Ancient Rome around the same time. You probably can't remember who was even in Deep Impact, but you can recite at least a handful of lines from Armageddon and sing along to that Aerosmith song with a quiet passion. By the same token, Latin is still the sexiest ancient language around while Etruscan mostly wallows in indecipherable obscurity.

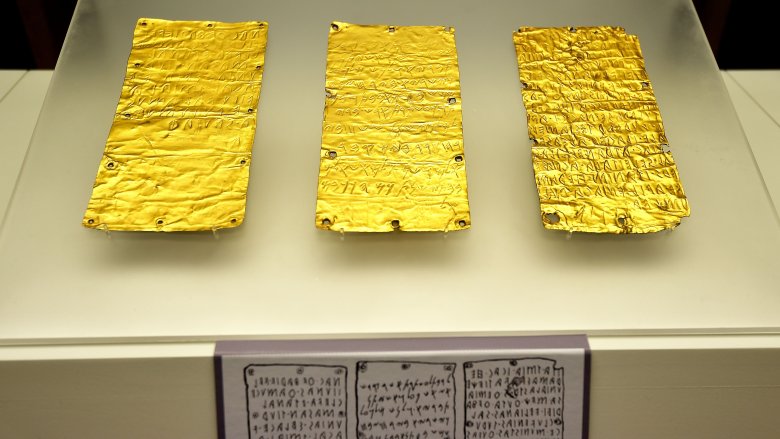

Before the Romans took over in 500 B.C., the Etruscans ruled much of Italy and still hung around for a while after their period of greatness came to an end. But while our knowledge of ancient Roman life is vast enough that we probably deserve a restraining order of some kind, today's archaeologists remain stumped about Etruscan culture in general. The Etruscan language is a particular enigma because it doesn't seem related to other nearby languages, and inscriptions left on permanent materials are remarkably hard to come by. Some words and grammatical properties are known from what little has been found. The discovery of a sandstone slab inscribed with 70 Etruscan letters and punctuation marks in 2016 opened things up considerably, but for the most part the language remains shrouded in mystery.

The tragic loss of Bo, one of the world's oldest languages

When a language is lost, a huge piece of cultural heritage is often lost with it. Crucial ties to the past seem irrevocably and tragically severed. So it was with Bo, one of the ancient languages of India's Andaman Islands that was, until recently, spoken by descendants of one of the world's oldest cultures.

In 2010, the last speaker of Bo died at the age of 85. As reported by Al Jazeera, her name was Boa Sr, and she was the oldest of the Great Andamanese, a tribe thought to have lived on the island for as many as 65,000 years. Despite having no one to talk to in her native tongue, she was a good-natured soul with an infectious laugh. She was also tough as hell, even surviving the massive tsunami of 2004.

Boa's loss and the loss of her mother tongue has underscored the plight of these people in general since the mid-19th century. The British, as they were terribly fond of doing, colonized the Andaman Islands in 1858, according to Survival International, and that went about as well as you'd expect for the locals. Originally ten distinct tribes, the Great Andamanese were 5,000 strong at the time, but most were killed by the settlers or by new diseases. Since then they've had to rely heavily on assistance from the Indian government, and alcohol abuse has been rampant. Today, only 52 of the Great Andamanese remain, and their voices are disappearing.

Manx Gaelic: how to revive a language in style

Death is not always the end, at least where language is concerned. Closely related to Irish and Scottish and traditionally spoken on the Isle of Man, Manx Gaelic started to decline dramatically in the 19th century as English picked up steam. As reported by The Guardian, poverty was rife on the island and people started to think the language was partially to blame, or that at least it didn't help. Still, some refused to simply let it die.

Strides were made throughout the 20th century, not least of which were the tape recordings (above) of the last native Manx speaker Ned Maddrell, who died in 1964. But the revival was administered that key shot of adrenaline with the establishment of Bunscoill Ghaelgagh in 2001, a primary school that teaches almost entirely in Manx. When Manx was declared extinct in by Unesco in 2009, children from the school wrote letters to the organization, asking (with a hearty dose of sass): "If our language is extinct then what language are we writing in?" Its classification has since been bumped to the slightly less alarming "critically endangered."

Technology has been at the forefront of the revival, with social media efforts, animation projects, and dedicated apps doing their part for education and preservation, and musicians have even been releasing music sung almost entirely in the ancient language. It may be working: 1,800 people said they could use Manx Gaelic in some form in the island's 2016 census. Not too shabby.

Eyak: the lost Native American language and the Frenchman who helped resurrect it

Almost 600 of the world's languages are listed as critically endangered, according to Unesco, and it'll probably come as no surprise to learn that most of these are in the Americas. The reasons are plain as day. Many Native American and First Nations children were taken from their families and sent to boarding schools in Canada and the U.S. where they were forbidden to speak their native tongue. This happened well into the 20th century, and many of these languages disappeared entirely. The Eyak language of the Alaska Natives is one such recent casualty.

Chief Marie Smith Jones, whose Eyak name means "a sound that calls people from afar," died in Anchorage in 2008 at 89. As reported by NPR, she was the last fluent speaker of Eyak, and in life she worked tirelessly to preserve her language and those of other indigenous Alaskans. This work might have been in vain had someone not been there to take up the mantle, and thankfully someone was. They just happened to be halfway across the world.

Since he was 13, Frenchman Guillaume Leduey had an inexplicable passion for learning and preserving the Eyak language. Good thing, too — he essentially resurrected it. After Chief Jones' death, he left France and teamed up with a linguist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks to work on a digital English-to-Eyak dictionary. This work is still trucking along nicely, ensuring Jones' spirit lives on through the sounds of her native tongue. Years of cultural genocide notwithstanding, people can occasionally be pretty swell.

Ubykh: too complex to endure

With only two vowels and 80 consonants in its alphabet, Ubykh isn't the kind of language you just pick up like you might pig Latin. There's a considerable level of complexity involved, which sadly didn't help Ubykh endure or prosper in the present. Its last native speaker passed away in 1992, taking the ancient tongue with him. And as is usually the case with lost languages, what's lost is really something beyond words.

Due to Russian subjugation of the Muslim population in the northern Caucasus in the 1860s, the Ubykh people were driven from their homes on the eastern shores of the Black Sea and scattered across Turkey. They left their rich cultural identity behind as they were forced to assimilate, and stopped teaching their children how to speak Ubykh in favor of more useful languages. Beyond this, according to linguist Stephen Anderson (via the Washington Post), a newly married couple would traditionally adopt the simpler language of the two just to make things easier. So whenever an Ubykh-speaking woman would marry a man who spoke a less demanding language, she'd kick Ubykh to the curb.

"What is lost when a language is lost is a world," according to Anderson. If there's anything positive to be said for the loss of Ubykh, it's that it has lit a raging fire under many in the world of linguistics and urged them to keep other similarly endangered Caucasian languages from suffering the same fate.

Sumerian: the progenitor of the fart joke

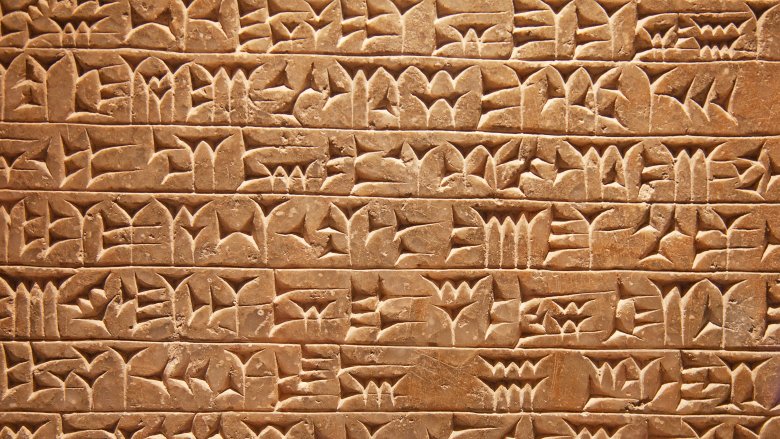

The Sumerians were basically The Beatles as far as ancient civilizations go, and even that's not giving them enough credit. According to Live Science, Sumerian culture blossomed and thrived in ancient Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) starting around 3500 B.C., boasting incredible skills in agriculture, art, architecture, math, astronomy, and basically everything short of interpretive beatboxing. On top of all that, Sumerian is the world's earliest known written language.

Sumerian was first used about 5,000 years ago, largely as a way of bookkeeping and bringing order to the advances Sumerians were making in basically every area. The form of writing they introduced was made up of small wedge shapes and known as "cuneiform," from the Latin cuneus, which means wedge. Some of the writings that would form the basis for one of the world's oldest major texts, the Epic of Gilgamesh, were originally written in Sumerian, as was the world's oldest recorded joke. It's really a testament to the glorious perseverance of the fart joke: "Something which has never occurred since time immemorial; a young woman did not fart in her husband's lap." That wouldn't feel out of place in a slightly-classier-than-average Adam Sandler movie.

Sumerian culture disappeared around 4,000 years ago, and the language followed soon after. It's thought that a 200-year drought brought on by climate change was partly to blame for the decline. It might not be with us anymore, but this language had one hell of ride.

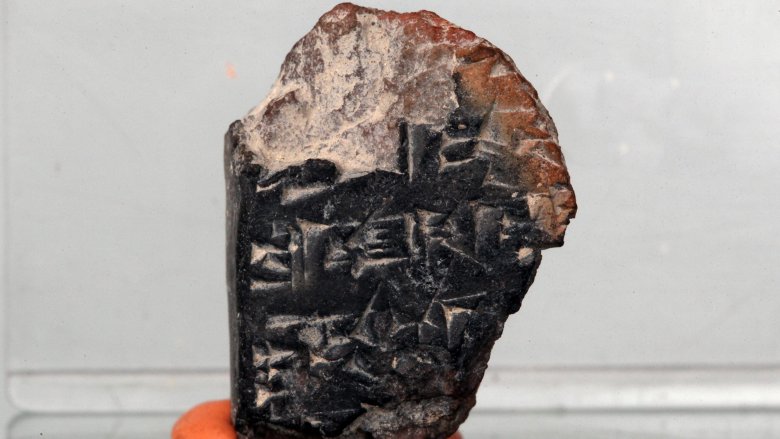

Akkadian: the dominant language of one of the first empires

Once the Sumerians decided they'd revolutionized enough already, Sargon of Akkad and his mighty Akkadian Empire said "we'll take it from here" and swept across Mesopotamia around 2500 B.C., as outlined by the Smithsonian. Sargon created the first Mesopotamian Empire, and the Akkadian language (also written in cuneiform script) replaced Sumerian as the dominant tongue in the region. It splintered off into other dialects over the next few centuries, but by 100 A.D. it had disappeared entirely. Of course, being a Semitic language, its grammar and structure are very similar to modern Arabic and Hebrew.

Scholarly interest in Akkadian certainly hasn't let up in recent years. A number of Akkadian riddles were found and translated on a 3,500-year-old tablet in 2012, suggesting they were every bit as fond of dumb toilet humor as their Sumerian neighbors, and in 2011 a 21-volume dictionary of Akkadian was published by scholars at the University of Chicago. This was a mammoth undertaking, 90 years in the making, and all 21 volumes can be viewed online for free. So if you've ever desperately wanted to read and understand the completed Epic of Gilgamesh in its original language to impress all your monocle-wearing friends, there's nothing stopping you.

Proto-Indo-European: the granddaddy of all Indo-European languages

English, Russian, Hindi, and numerous other languages spoken in Europe and Asia can all be traced back to this bad boy, according to Archaeology magazine. Its influence and historical significance are vast and undeniable. What's more contentious, however, is exactly what it sounded like and how it should be translated. And that's mainly because it's so old that it predates writing.

Called PIE for short, the language was spoken from around 4500 to 2500 B.C., and linguists have tried to reconstruct it using shared words from different languages they think grew out of PIE. So yeah, the lack of written texts makes things really difficult. Scholars have been attempting to reconstruct PIE and approximate its sound and proper usage since at least 1868, when German linguist August Schleicher created a fable — about a sad sheep and a band of equally sad horses — using his own reconstruction of the language's vocabulary to hear what it might have sounded like. The fable and the manner of speaking it has been updated intermittently over the years, informed by new insights and reconstruction strategies, and which version should be considered definitive has been the subject of much scholarly bickering and debate over many stuffy games of chess and backgammon, probably.

Coptic: our last link to Ancient Egyptian

An Egyptian language written (mostly) in the Greek alphabet, Coptic ultimately replaced that neat, recognizable hieroglyphic writing style as Christianity spread through Egypt around the second century A.D. It flourished until Arabic became the dominant language in the country in the seventh century, and Coptic eventually disappeared from everyday use.

This ancient language was initially introduced as a way of easily translating holy books from Greek, but Coptic also encompassed a rich culture of art and literature outside religion, and that's a world that's been lost for the most part. The Coptic church is still a thing (it even has its own pope, shown above), and the language mostly exists for religious rituals today. You aren't likely to hear it used outside of certain Orthodox churches. And even then, there are Coptic churches in the United States that don't use the language in their liturgy, according to The Atlantic. There has been some effort to revive it beyond these stuffy confines, and there are a couple of places in Egypt where Coptic classes are available, but there's still cause for concern. As the final stage of the Ancient Egyptian language, Coptic's survival represents another invaluable link to the past — and its cultural riches — that is on the brink of disappearing.