The Story Behind Operation Thunderbolt, One Of The Korean War's Deadliest Battles

While it may not be as widely discussed as WWII or the Vietnam War, the Korean War was every bit as important, and bloody. Aptly nicknamed "the Forgotten War," Korea kicked off just a few years after the end of WWII when the Cold War was still in its infancy. As Dean Rusk, who served as Secretary of State throughout the 1960s, explained in his autobiography "As I Saw It," the Korean peninsula was initially divided in the waning hours of WWII, and American troops were only kept on the continent "for symbolic purposes."

Fast-forward five years to June 25, 1950, and North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung authorized the invasion of the southern half of Korea after getting permission from the leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin (per Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov in "Inside the Kremlin's Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev"). Using huge amounts of Soviet-made weapons and artillery, North Korea burst across the 38th parallel and plunged headfirst into South Korean forces in a vain attempt to bring about the reunification of the country. Stalin was under the mistaken belief that the U.S. would not risk manpower and money to stop the onslaught, but he could not have been more wrong.

In the resulting war that lasted until 1953, almost 5 million people died, including roughly 40,000 Americans (via History). This is the story of Operation Thunderbolt, one of the Korean War's deadliest and most pivotal battles.

Crossing the Yalu River

The Korean War first broke out in June 1950, when 90,000 troops from the Democratic People's Republic of Korea invaded the southern part of the peninsula, the Republic of Korea (via the "History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff During the Korean War"). President Harry Truman quickly authorized the U.S. to support South Korea to prevent the fall of key areas, and within days heavy bombers were dropping ordnance to stop the onslaught. However, more than half the South Korean army was gone, leading Truman to introduce an American regimental combat team to help the beleaguered fighters.

Soon, the U.S. had secured a U.N. resolution condemning the invasion and authorizing the creation of a U.S.-commanded military force to intervene. However, this failed to stop the North Korean advance, and the capital of Seoul soon fell. It wasn't until after the famous Inchon landing in September, that the U.S.-led forces finally re-took Seoul and evicted the communists (via History).

However, the U.N. forces then invaded North Korea, which provoked the Chinese army to enter the war on North Korea's side by sending 180,000 troops south across the Yalu River. They once again beat the U.S. troops back into South Korea, recapturing Seoul in early January (via the Marine Corps University). Days later, the U.S. finally halted the advance, opening the door for Operation Thunderbolt, the first allied counteroffensive (via The U.S. Army War College).

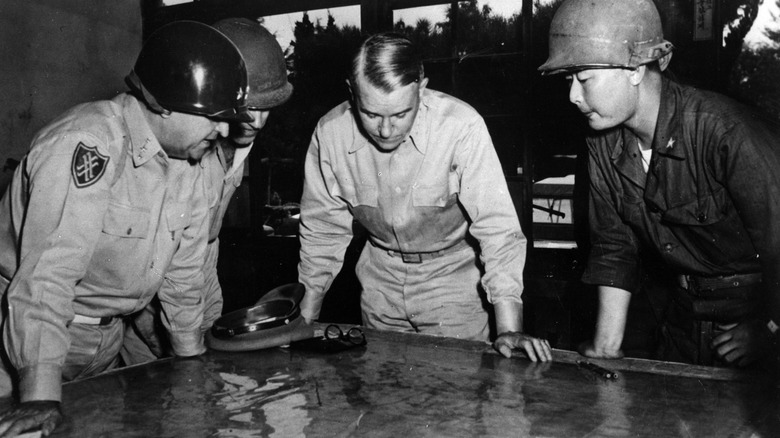

Matthew B. Ridgway, the commander of Operation Thunderbolt

If there is one name that is synonymous with the American intervention during the Korean War, it is the former commander of U.S. forces Matthew B. Ridgway (pictured). A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and veteran of the Second World War, Ridgway served in various high-level positions within the military and government until Korea broke out in 1950 (via the National Museum of the U.S. Army). That December, the commander of U.S.-led forces in Korea, General Walton Walker, was killed following an automobile accident, thrusting Ridgway into the top position (via Max Hastings in "The Korean War").

He was in a perilous situation, with a demoralized group of troops who had been facing a relentless Chinese and North Korean offensive for months. Not only that, but winter was fast picking up steam on the Korean peninsula, and the men were severely lacking in everything from food and necessities to basic winter gear.

However, from the second Ridgway took over, there was a distinct change in the air. He revamped the strategy and impressed his troops with his leadership, organization, and attention to detail. Ridgway put a halt to the Chinese assault, and soon would lead U.S. forces in a counterattack. Ridgway would attain the rank of a full general in 1951, and would later become the Supreme Allied Commander of Europe and Army Chief of Staff, until his retirement in 1955.

Operation Wolfhound

The direct predecessor to Operation Thunderbolt was known as Operation Wolfhound, and it began on January 15, 1951. The week prior, on January 7, the Chinese offensive that had begun the previous October was finally halted by Matthew B. Ridgway and the U.N. force of troops (via the Marine Corps University). Wolfhound, so called because of the participation of the "Wolfhound" regiment — the 27th Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division — was an attack on the Osan and Suwon areas held by the communists (via Lt. Col. Roy E. Applemann in "Ridgway Duels for Korea").

The troops consisted of elements of the 3rd and 27th Infantry Divisions, 89th Tank Battalion, 8th Field Artillery Battalion, 90th Artillery Battalion, and 65th Engineer Combat Battalion, along with multiple divisions of Republic of Korea troops. During the operation, which was part attack and part reconnaissance, U.N. troops found many civilian casualties in the surrounding areas. There was also a massive aerial bombardment consisting of 107 sorties, which killed nearly 1,000 enemy troops.

At 11:30 on the 15th, troops from the 2nd Battalion of the 27th Infantry under Capt. Jack Michaely ran into Chinese resistance at Suwon, and hundreds of Chinese soldiers perished in the ensuing air attacks. Compared with the heavy amount of Chinese casualties, the Wolfhound forces only suffered three dead and seven wounded, and they captured five prisoners, marking the small operation a resounding success.

Task Force Johnson

Following the events of Operation Wolfhound, U.S. Commander Matthew B. Ridgway was still concerned with reconnoitering the surrounding area. According to Billy C. Mossman's "The United States Army in the Korean War: Ebb and Flow: December 1950–July 1951," the area was thought to be free of enemy troops, but Ridgway still ordered various patrols to get a better picture. One of those patrols was led by the colonel of the 8th Cavalry, Harold K. Johnson, and was known as Task Force Johnson (TFJ).

On January 22, 1951, TFJ began its patrol of the Kumyangjang-ni-Ichon road, where they ran into enemy resistance. With help from the Air Force, they were able to inflict 75 casualties before running into more trouble from the west (as per Lt. Col. Roy E. Applemann in "Ridgway Duels for Korea"). More airstrikes, which utillized bombs and napalm, inflicted hundreds more casualties on the enemy forces, compared with only a few wounded on the American side.

The reconnaissance patrols had been a success, showing that the areas surrounding the I and IX Corps were relatively unoccupied by enemy troops. Reports from the Air Force showed a troop buildup north of the Kumyangjang road, but overall the news was largely positive.

The reconnaissance phase

After Operation Wolfhound and the Task Force Johnson patrol, U.S. commander Matthew B. Ridgway had a much better understanding of the enemy Chinese and North Korean forces in front of him, but he still wanted more information. Wary of wantonly committing too many forces to battle against an unknown number of enemies, on January 23, 1951, Ridgway ordered Operation Thunderbolt, another reconnaissance mission, to commence two days later on the 25th (via "The United States Army in the Korean War").

His orders were to find enemy forces by probing as far as the Han River to the north. In preparation for the attack, the day before it kicked off Ridgway and General Earle Partridge actually surveyed the area from an aircraft. Upon seeing no obvious enemy forces, Ridgway gave the okay for Thunderbolt to proceed, and it began on schedule the next day. The first phase ran from roughly January 25–January 31, before it changed from reconnaissance into offensive (via "Restoring the Balance").

The I and IX corps were able to recapture major cities like Osan, and pushed 20 miles closer to retaking the capital of Seoul. In addition to U.S. and Korean forces, there was also a Turkish battalion taking part in Thunderbolt, and they fought a severe battle against the Chinese at Kumyangjang-ni, which they won. Along with taking territory, the U.S. forces also took many prisoners, who largely confirmed their suspicions of weak resistance ahead.

From reconnaissance to offensive

After realizing he was getting closer to the main Chinese line and running into increasing resistance, U.S. commander Matthew B. Ridgway decided to make a tactical change (per "Restoring the Balance"). At this point, Operation Thunderbolt had been conceived and executed as mainly a reconnaissance mission, but now it changed and became an offensive attack. While he had discounted the idea of retaking Seoul at this stage, Ridgway still wanted to disrupt Chinese and North Korean forces from regrouping (according to "The United States Army in the Korean War").

In addition to American and Turkish forces, more South Korean troops joined the fray, and they all continued to push toward the Han River. In particularly fierce fighting on February 1, 1951, over 80 air strikes were called in at the cost of thousands of Chinese soldiers. To supplement Thunderbolt, Ridgway now also began Operation Roundup on its immediate right flank, which commenced on February 5.

Thunderbolt continued alongside Roundup through February 11; on February 10, U.S., Turkish, and South Korean troops all made it to the southern banks of the Han River. Yet, while the U.S.-led forces had advanced a considerable amount over the last week, North Korean and Chinese troops were amassing on the other side of the river, already planning a counterattack of their own.

The Battle of Hoengsong

Following the success of Operations Thunderbolt and Roundup through February 11, 1951, things were looking up for the U.S.-led forces in Korea. However, their Chinese and North Korean foes were far from vanquished. Having been pushed back more than 20 miles to the banks of the Han River in some places, they now began to push back. The ominous sound of bugles and drums declared the beginning of the 135,000-troop-strong communist counterattack, and soon the snow in the town of Hoengsong was covered in blood (via "Restoring the Balance").

Within hours, the 8th Division of the South Korean army was completely obliterated, incurring more than 7,100 casualties (as per "The United States Army and the Korean War"). In addition to casualties, they also lost large amounts of weapons, artillery, and equipment, including nearly 70 trucks and thousands of rifles. With allied forces in a retreat, they had to withdraw entirely from Hoengseong on February 13, less than a week after it had been recaptured. The communists also extended their attacks westward at Chip'yong-ni, where they soon surrounded the 23rd Infantry Division.

It was at Chip'yong-ni that Ridgway decided to make a stand, fearing what would happen to his flanks should the 23rd Infantry fall. In preparation for another severe counterattack, Ridgway also began strengthening forces at the Wonju line, just south of Chip'yong-ni.

Defending Chip'yong-ni and the Wonju Line

After making solid progress from January 25 through February 11, 1951, Operation Thunderbolt stalled. Facing stiff resistance along the Han River at Chip'yong-ni and with fierce battles in towns like Hoengsong to the east, U.S. commander Matthew B. Ridgway ordered his forces to hold the line as long as they could (according to "Restoring the Balance"). The two main areas of allied resistance were at Chip'yong-ni and the Wonju Line, which is where the remaining South Korean troops withdrew following the abandonment of Hoengsong (via "The United States Army and the Korean War").

Unfortunately, Ridgway had a big problem, in the form of a 12-mile gap that opened between the Wonju and Chip'yong-ni lines. The Chinese began attacking the gap on February 12, but were repulsed. Facing simultaneous attacks at both Chip'yong-ni and Wonju, American forces remained steadfast in the face of an incredible communist onslaught. Eventually, by February 18, the communists had withdrawn from the attack after being unable to break through, realizing its continued futility and conscious of outstretched supply lines.

Immediately following the conclusion of the battles at Chip'yong-ni and Wonju, Ridgway ordered American forces to retake the offensive once again as part of Operation Killer, which began on February 20 (via "Restoring the Balance"). The following month, allied forces would finally cross the Han River and retake Seoul, again, as part of their renewed push back north.

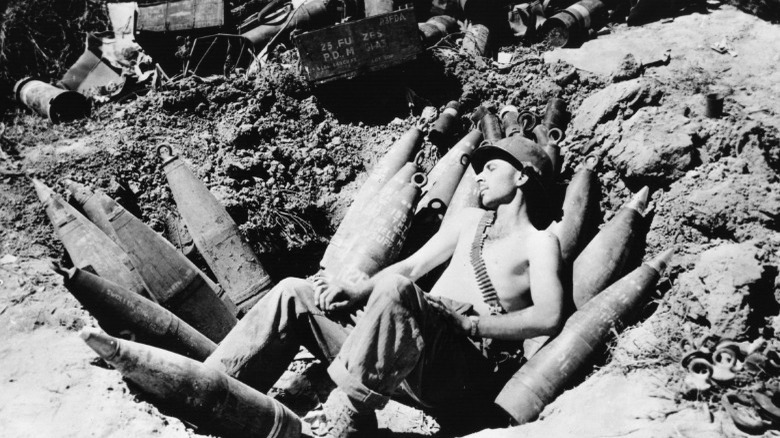

The horrific casualties

The fighting during Operation Thunderbolt marked some of the most brutal and bloody combat of the entire war. According to the "Korean Battle Chronology: Unit-by-Unit U.S. Casualty Figures and Medal of Honor Citations," there were a total of 6,861 U.S. casualties from January 25–February 20, 1951, during Thunderbolt. For the most part, the casualties were pretty spread out, with the exception of the fighting on February 12, during the Battles of Chip'yong-wi and Hoengsong, when there were more than 1,000 casualties in a single day, of which 259 were fatalities.

That does not even take into account the losses from the South Koreans, which were incredibly horrific. During the Battle of Hoengsong and subsequent withdrawal, the South Koreans lost nearly 10,000 troops in a three-day period (as per "The United States Army and the Korean War"). The vast majority of those were from the 8th Republic of Korea Division, which lost more than 7,400 soldiers alone. During the same battle, U.S. and U.N. forces were limited to just over 2,000 casualties, of which nearly 1,800 came from the 2nd Division alone.

The Chinese and North Koreans also faced large casualties from the allies. Airstrikes and artillery fire on February 1 alone caused more than 1,300 deaths and 3,600 total casualties, and thousands more perished in other battles during the month of Thunderbolt (via Max Hastings in "The Korean War").

Thunderbolt's aftermath

Following the success of Operation Thunderbolt in pushing the Chinese and North Korean forces back, U.S. commander Matthew B. Ridgway wasn't about to rest on his heels. In an action that decimated the enemy forces south of the Han River, Ridgway ordered Operation Killer to commence on February 21, 1951, the day after Thunderbolt ended (according to "Restoring the Balance"). It lasted for two weeks, though it took the units only a week to complete their objectives, but U.S. forces took heavy losses (via "Korean Battle Chronology").

From February 21–March 6, 185 U.S. Army soldiers lost their lives during Killer, as did 18 members of the Air Force, most of whom died after going missing. The Marines also had 76 fatalities, and the Navy lost two men. One man, Sgt. Einar H. Ingman Jr. of the U.S. Army, was awarded the Medal of Honor for sustaining wounds while single-handedly taking out two gun crews.

Following Operation Killer, Operation Ripper lasted from March 7 to April 3. The plan was to continue the success of Thunderbolt and Killer, and push even farther north toward the 38th parallel. Ripper was another costly operation, as 674 U.S. Army soldiers, 71 Marines, two sailors, five Navy pilots, and 41 Airmen died; thousands more American service members were wounded in action. Sfc. Nelson V. Brittin of the Army was awarded the Medal of Honor during Ripper for killing more than 20 enemies during multiple thrusts before succumbing to his own wounds.

There were many Medal of Honor recipients

It's hard to believe, but the U.S. Army gave out no less than eight Medals of Honor to soldiers fighting as part of Operation Thunderbolt (via "Korean Battle Chronology"). The first medal went to 1st Lt. Carl H. Dodd, who on January 30-31, 1951, was at the head of successive attacks against enemy positions during the capture of Hill 256 near Subuk. On the same night, at Kumyangjang-ni, 1st Lt. Robert M. McGovern earned a medal for sacrificing himself during an attack that killed multiple enemies.

On February 1, M/Sgt. Hubert L. Lee earned a medal near Ipori for continuing to lead attacks and fight against the enemy, even after being wounded three times, including in both legs. Three days later, on February 4, M/Sgt. Stanley T. Adams earned a medal for leading a bayonet charge and fighting even after sustaining multiple wounds at Sesim-ni. Just over a week later, for his actions on February 12 at Hoengsong, which included putting himself in severe danger to help direct mortar fire, Sgt. Charles R. Long earned his medal. Two days later on February 14 at Chip'yong-ni, Sfc. William S. Sitman earned a medal when he jumped on an enemy grenade just before it exploded.

The final two Medals of Honor went to Capt. Lewis L. Millett and 2d Lt. Darwin K. Kyle. At Soam-ni, Millett was wounded and engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat, and Kyle died following a daring bayonet charge at Kamil-ni.

Thunderbolt's impact on the Korean War

Even though the story of Operation Thunderbolt isn't exactly common knowledge except among serious history buffs, it still played a very important role during the Korean War. After the Chinese entered the war in October 1950 and began the second communist offensive, morale for the 8th Army was incredibly low. When he took over that December, U.S. commander Matthew B. Ridgway found his troops dispirited, underfed, and under-clothed, and still reeling from the months of fighting fresh Chinese troops (via Max Hastings in "The Korean War").

However, once Ridgway took over and Operations Wolfhound, Thunderbolt, Roundup, Killer, and Ripper commenced, everything changed. The 8th Army was reinvigorated with fighting spirit, and they began to take pride again in their appearance and fighting style. According to Hastings, the battle of Chip'yong-ni, which saw the Chinese throw some of their best units against the Americans, stood out in particular as a moment of regaining morale.

In addition to restoring the soldiers' faith in the Army, Thunderbolt also represented a turning point in overall U.S. strategy. As the U.S. Army War College points out, Thunderbolt, Roundup, Killer, and Ripper were the first counterattacks following the Chinese entry into the war, leading to their pushback past the Han River and 38th parallel. Just a few months later, President Harry Truman would initiate peace talks, though an armistice would not officially be signed until the summer of 1953, which finally brought the war to an end.