The Horrifying Pease River Massacre Of 1860

On the morning of December 19, 1860, it was cold in Texas. Along Mule Creek, near where it met the Pease River in modern Foard County, a group of Texas Rangers stumbled upon a Comanche encampment. What happened next depends on whose version of the story you believe — so says Paul Carlson, professor emeritus of history at Texas Tech.

What's pretty certain is that the Rangers emerged victorious, many of the Comanche they encountered, while suffering no injuries or casualties themselves. How many people died and who they were, exactly, differs by the telling. So does the number of Comanche who escaped and the number of horses the Rangers took with them after their victory (via Texas Monthly).

The Rangers definitely captured three members of the Comanche group afterward: a boy and a woman with a young child. The victorious leader of the Rangers, Sul Ross, took the boy home with him, according to Carlson. The woman, Naduah, had been born Cynthia Ann Parker, and she was one of the most famous white captives in frontier history, having been taken from her family by the Comanche when she was around 11 (via Texas Monthly). She was reunited with her white family but longed for the Native American one she'd left behind. Parker's story was just one of many tragic aspects of what happened that day near the Pease River.

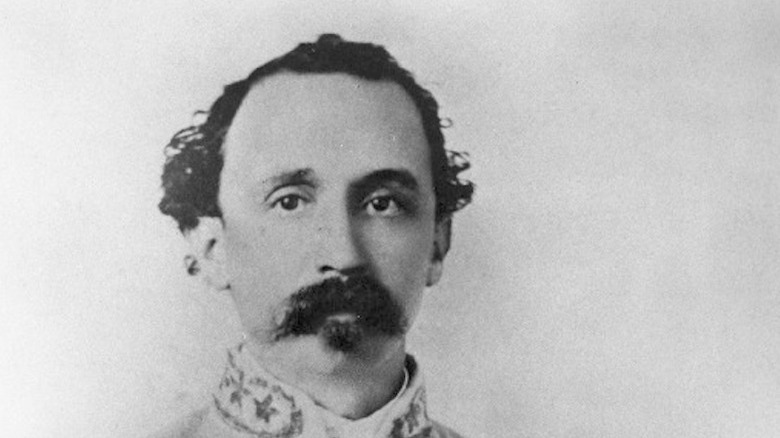

Who was Sul Ross?

For a long time, Sul Ross's version of the story was the definitive one, widely believed even by historians. He said the Rangers had been outnumbered by Comanche warriors and emerged heroically victorious anyway, according to Carlson (via YouTube). He had good reason to want to look heroic. Initially, he was trying to salvage his reputation after a different, botched campaign against the Comanche. Later, he was trying to win elections to the state senate and then the governorship of Texas. One of his contemporaries outright admitted that the Pease River incident had won Ross the governorship, according to Texas Monthly.

Ross grew up in Waco. Before becoming a politician, he was a Confederate general in the Civil War. By the end of his life, he was president of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M University). Ross was only 22 during the Pease River incident. Two years before, he had been wounded by a Comanche chief named Mohee during a conflict.

Conflicts between white settlers and the many bands of the Comanche were common in the 1850s and 1860s. The Comanche had dominated Texas a generation earlier, but their numbers were dwindling by 1860, and they were suffering from European diseases and the loss of buffalo, per the Texas State Historical Society. Nonetheless, they were still regularly raiding white settlements. The Pease River incident — which they called a massacre, while Ross called it a battle — was partially a retaliation for those raids.

Ross's version of the incident

While Ross's accounts of the "battle" of Pease River were always meant to make him look good, they changed with time, becoming more grandiose. Shortly after it happened, he told the Dallas Herald newspaper his group had killed 13 Comanche, while he told Governor Sam Houston it was 12. By the next year, he'd added a detail about personally fighting and killing a Comanche chief afterward. In 1875, he told the Galveston News the chief in question was Mohee, who had previously wounded him. Mohee had probably actually died before the Pease River massacre; maybe that's why Ross later said it was Chief Peta Nocona he'd fought and killed (via Texas Monthly).

Ross had help in shaping this narrative, according to Carlson (via YouTube). A former Texas Ranger, Benjamin Franklin Golson, gave interviews about it and claimed they'd actually fought hundreds of Comanche — the rangers were vastly outnumbered, he said — then chased some who'd tried to get away. The problem with Golson's story is that he wasn't actually there.

Ross embellished his story with help from a journalist friend, Victor Rose, to whom he actually admitted he was doing it to help himself politically. Another friend, James DeShields, published a book on Cynthia Ann Parker in 1886 that described the incident as an unprecedented victory over the violent Comanche, per Carlson. It became one of the definitive sources about the incident. Conveniently, the book was published while Ross was running for governor, per Texas Monthly.

Alternate versions of the incident

In 2021, Texas Monthly interviewed Ron Parker about the Pease River incident. Parker is the great-great-grandson of Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker. He'd grown up hearing a very different version of the story: it was a massacre of Comanche, and Nocona wasn't even there. This account actually matches a couple of contemporary ones. Reflecting on the incident in 1928, Texas Ranger Hiram B. Rogers said he wasn't "very proud" of his participation in it. "That was not a battle at all, but just a killing of [women]" (via Texas Monthly).

John or Jonathan Baker was part of a volunteer militia that was helping Ross but wasn't present at Pease River. When his group caught up with Ross that day, Ross told them he and the Rangers had encountered 15 Comanche, killed 12, and captured three. However, Baker's group only found seven bodies — four female and three male, possibly young boys, per Texas Monthly.

Carlson's research, with former attorney and judge Tom Crum, led them to describe the actual incident thus: "20 federal troops, not more ... surprised and struck a small Comanche hunting camp." They believe there really were about 15 people in the camp, mostly women and children, and that, based on Baker's account, the Rangers killed seven and captured three, while the other five escaped. They think the entire massacre only lasted about 20 minutes (via YouTube).

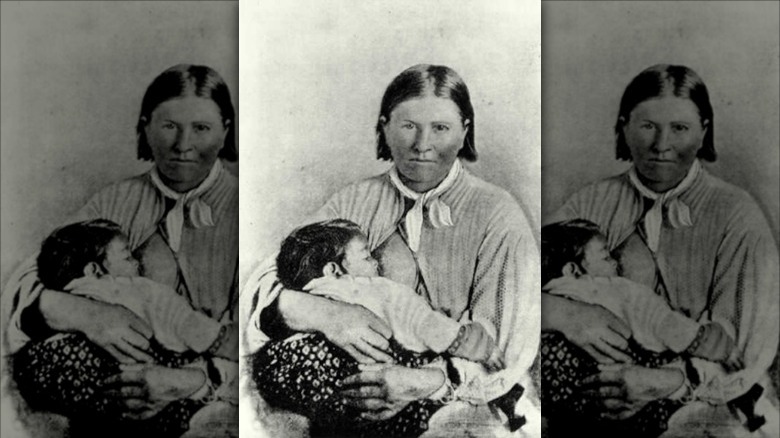

Who was Cynthia Ann Parker?

Cynthia Ann Parker, aka Naduah, was born around 1825 in Illinois. About 10 years later, her family built Fort Parker on the Navasota River in Texas, per the Texas State Historical Association. On May 19, 1836, a group of allied Native American tribes attacked the fort, killing several people and capturing five, including Parker and her brother John. All were later released except Cynthia Ann Parker. She may have stayed by choice — allegedly, when John left the Comanche, he asked his sister to come with him, but she refused.

Parker totally assimilated with the Comanche. When federal officials encountered her in the late 1840s, they found she was a "full-fledged" member of the tribe. When she and her daughter Topsannah were captured after the Pease River massacre, Parker no longer spoke English. They were taken to see her uncle, Col. Isaac Parker, who positively identified her. He became her state-appointed guardian for a while. Later, she moved in with her brother Silas Parker, and later still, with a sister (via Texas State Historical Association).

Carlson says that both times Parker was captured, it was "against her will" (via YouTube) By 1860, she'd lived with the Comanche for nearly 25 years and shared their beliefs. She had married a Comanche warrior (Nocona) and had three children with him. She never saw her two sons again after Pease River. She unsuccessfully tried to run away to rejoin them, per the Texas State Historical Association. Carlson says she "suffered immeasurably."

What happened to Nocona?

The fate of Parker's husband, Peta Nocona, after the Pease River massacre, is uncertain. The Texas State Historical Association notes that in a famous photograph of her and Topsannah, she has short hair — a sign of mourning for the Comanche — because she believed Nocona was dead. However, her oldest son, Quanah Parker (pictured), stated firmly his father wasn't at the massacre, despite what Ross said. He told several people his father died about five years later, per Texas Monthly. Crum and Carlson's research supports that statement (via YouTube).

In addition, circa 1877, Quanah Parker told rancher Charles Goodnight — who famously considered Ross a liar — that the chief killed in the massacre was named Nobah. Crum believes that before DeShields' book came out in 1886, Quanah Parker didn't know his father was supposed to have died in the incident, so he would have had no reason to lie about it in 1877. Quanah Parker's statements were backed up by Horace Jones, a U.S. Army interpreter, who claimed to have spoken to Nocona at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, about a year after the Pease River massacre.

There has been confusion about whether Cynthia Ann Parker's sons were at the massacre or not, but she said they weren't. Quanah Parker certainly survived, later becoming a Comanche chief. However, his tribe's fortunes continued to decline after Pease River, and they were forced onto a reservation in 1875 (via Texas State Historical Association).