Joe DiMaggio's Father Was A Target Of Xenophobia During WWII Despite His Son's Fame

By early 1942, the once bustling Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco had become a virtual ghost town. The thriving crab and fish stalls, seafood restaurants, and swinging nightclubs were quiet. The formally formidable fishing fleet shrunk from 400 to 40. The U.S. had entered World War II and banned all the Italian-Americans who hadn't become U.S. citizens from coming within a half-mile of the California coast.

Fishermen of Sicilian descent had dominated the industry around San Francisco for years, and many of the older immigrants who'd come to America at the turn of the century hadn't become citizens. The U.S. government now classified them as enemy aliens. They were under a curfew, couldn't travel more than five miles from their homes, weren't allowed to own radios. In some cases, the government rounded them up and put them into detention camps, but nowhere near the numbers as their Japanese American neighbors.

The enemy alien and baseball hero

Among these older Italian fishermen was one, Giuseppe DiMaggio, who the government not only barred from getting to the coast to earn his living fishing but kept him from being able to go to the restaurant his sons owned at Fisherman's Wharf, where he took great pride in preparing his beloved spicy fisherman's stew for the guests. The family had owned the restaurant, "Joe DiMaggio's Grotto," since 1937 when Giuseppe's son Joe had supposedly invested $25,000 in the business, money earned through his skills on the ball field.

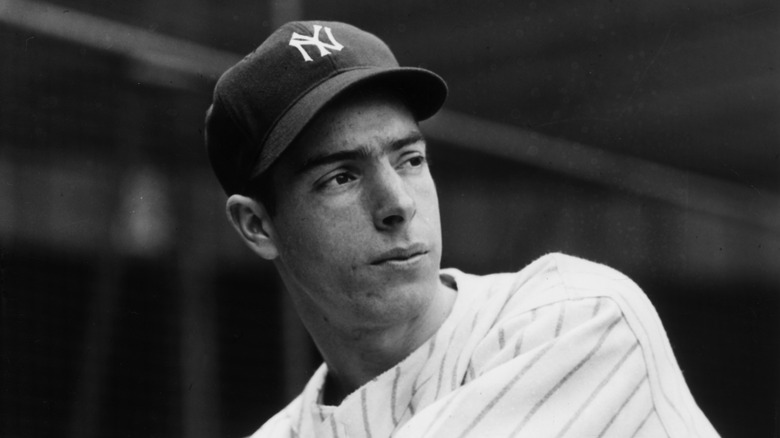

While Giuseppe suffered under the strictures of a xenophobic wartime policy, his son was being hailed as Joltin' Joe, America's baseball hero. In 1941, the New York Yankees' star player made history with his record 56-game hitting streak. Joe DiMaggio, Giuseppe and Rosalie's eighth child of nine, was born in 1914 in Martinez, California. Instead of following in his father's footsteps, he focused on baseball, dropping out of high school at 16 to pursue the sport full-time, and by 1936 earned a spot with the Yankees.

The DiMaggios become the face of their people

In February 1942, a San Francisco attorney and friend of the DiMaggio family, Chauncey Tramutolo, went to bat for the West Coast's Italian American community and made Giuseppe and Rosalie DiMaggio the face of their plight at a Congressional hearing on "National Defense Migration." Gen. John DeWitt had proposed including German and Italian enemy aliens in their plans to remove them from California, Oregon, and Washington state, along with Japanese Americans.

Tramutolo argued that many of the first-generation children of Italian-American non-citizens were in the armed forces and that removing their families from their homes would lower morale. He used the DiMaggios as exemplars of their community. "Joe, who is with the Yanks, was leading hitter for both the American and National Leagues during the years 1939 and 1940," he told the House members, according to the official record of the hearings. "The senior DiMaggios, though noncitizens are as loyal as anyone could be. To evacuate the senior DiMaggios would, in view of the splendid family they have reared and their unquestioned loyalty, present... a serious situation."

The argument worked, and the DiMaggios and other Italian American families were, in most cases, allowed to stay in their homes. Japanese Americans weren't as fortunate. The U.S. government forcibly removed more than 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast during the war and held about 120,000 in internment camps.